Charles Pierre Baudelaire (1821 – 1867) was a French poet, essayist, art critic, and translator of Edgar Allan Poe. He’s best known for Les Fleurs du mal (The Flowers of Evil), an extended Modernist prose poem about where one might find beauty in modern, rapidly industrializing mid-19th-Century Paris. Baudelaire influenced a whole generation of Fench poets including Paul Verlaine, Arthur Rimbaud, and Stéphane Mallarmé, among others, and also 20th-Century artists as diverse as 60’s rock star Jim Morrison and Portuguese author Fernando Pessoa. He coined the term “modernité” to designate the fleeting, ephemeral experience of urban life and claimed that the primary responsibility of modern art was to capture and, in so doing, transform that experience.

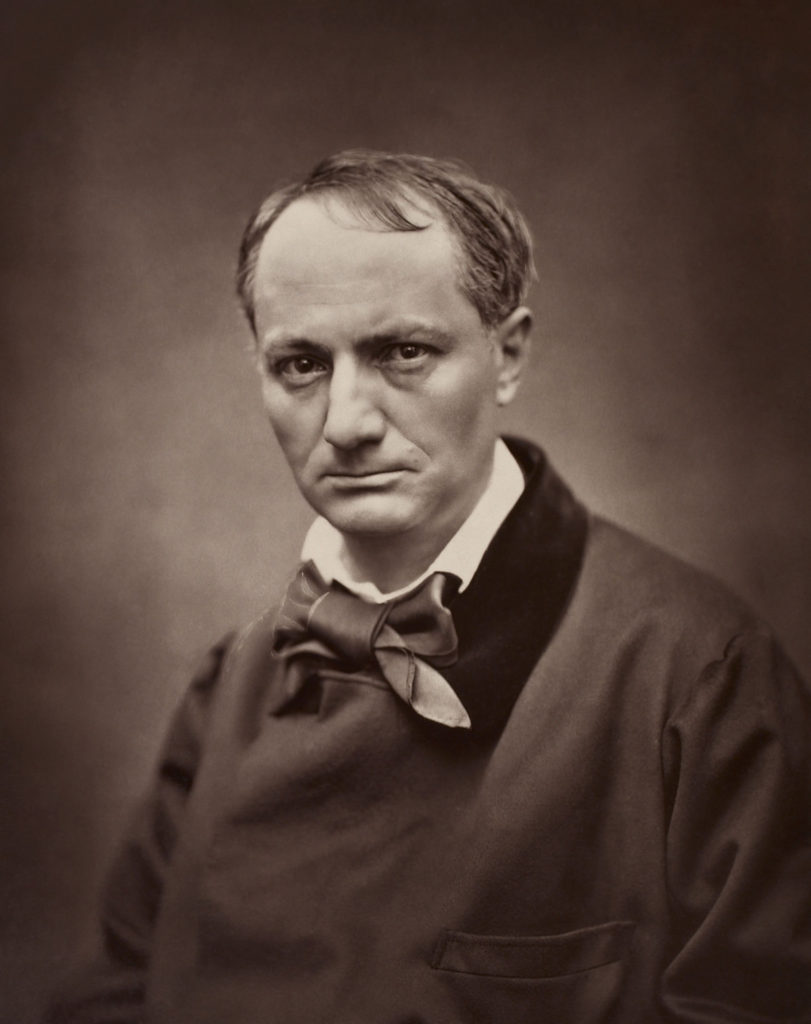

While Baudelaire lay on his deathbed, dying of syphilis, his mother found two photographs of him he had secreted in his overcoat; apparently, he’d been keeping the two photos on his person, a hidden, guilty pleasure of some sort. In one (that’s it above), he stares aggressively at the camera as if trying to directly meet the unmediated gaze of the ultimate viewer of the photo. Frankly, he looks pissed off, as if the camera itself were his enemy, something put between him and viewer, something that obscured the potential of a meaningful relationship between him and the person who’d view him as the subject of the photo.

Baudelaire had been interested in photography since the 1850s. French photographer Nadar, (Gaspard-Félix Tournachon (1820 – 1910), was one of Baudelaire’s closest friends until Baudelaire’s death in 1867 (Nadar wrote Baudelaire’s obituary in Le Figaro). Nadar remains one of the great early photo-portraitists, his portraits held by many of the great national photography collections.

In spite of his interest in photography and his friendship with Nadar, Baudelaire never much liked photography as a means of getting at anything subjectively truthful. He thought the camera’s lens “a dictatorship of opinion,” a device that made an end-run around the active self-questioning required of a viewing subject. Photography could not, according to Baudelaire, encroach upon “the domain of the impalpable and the imaginary”; it was competent only as a means to document objective facts.

According to Baudelaire, only with an “embodied vision”, actively interrogating what one looked at, could you possibly gain any sense of mastery over the perceived object, and such active interrogation only became possible when the subject of one’s gaze could gaze back. Real subjective visual truth came only when there could be a reciprocal interaction of the viewer and the subject. Rather than the one-sided transaction implicit in much of Western visual art – painting or photography – Baudelaire’s idea of a truthful visual representation would be a “forest of symbols” that looked back at you “with familiar eyes.” Using this criterion, photographic portraiture was, at best, caricature.

*************

In secular Western culture, where science and rationality are presumed to give us insight into what is “true,” we are used to seeing the material world through the lens of science, where subjects are turned into objects and placed in categories. Photography aides that process by its ability to document objective facts, and Baudelaire saw that as a legitimate use of photography. For Baudelaire, the problem came with photography’s attempt to capture the subjective. It can’t, because it can’t look back. There’s no real interaction between the viewing subject and photographic subject. Relationship, that which underlies subjectivity, is impossible in the one-sided encounter offered by a photograph. The image will always be distorted.

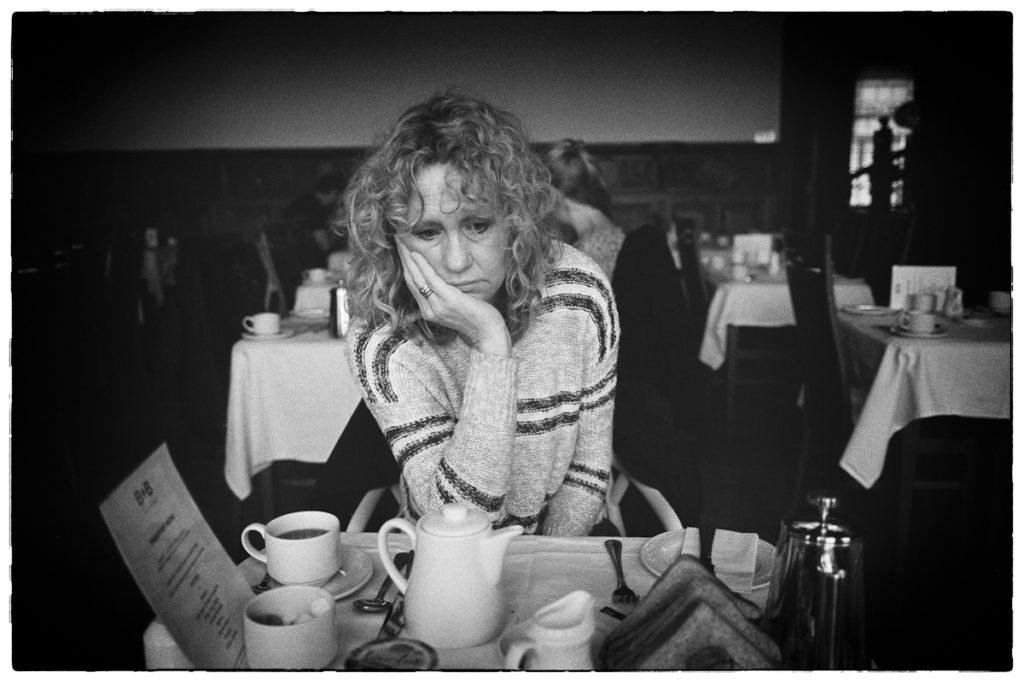

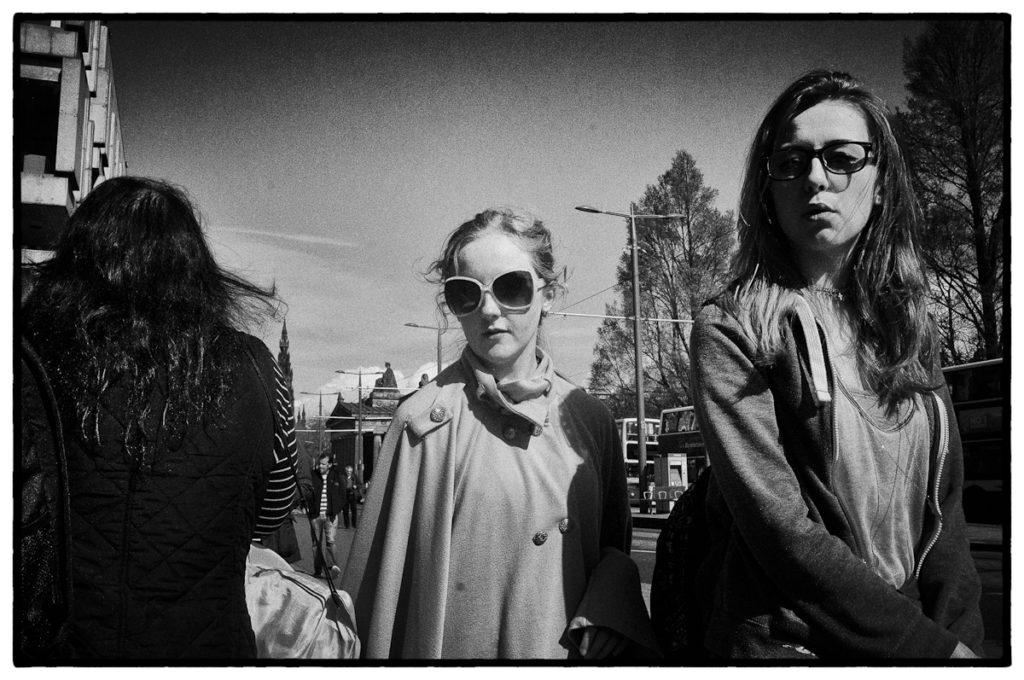

Compare what happens when you look at a photograph of a woman, how you look at it, with the way you look at that same woman encountered in the flesh, on the street; how you do so determines whether or not you let her look back. “Truth” is found in the reciprocal gaze, between subject and object, between the man and woman walking past each other in the street.

Baudelaire would say that modern man suffers from a distorted visual culture created by the ubiquity of photographic images. Given the extent to which photography has been normalized and now embedded in our societal consciousness, it has led us away from the truth. It has distorted our ability to understand others. It gives us only a superficial caricature, a false representation of other people, visual images of persona as opposed to the person themselves. Capitalist consumerism uses its distortions to make us want things, playing on our imagination because the image can’t interact with us. We see other people in this “post-truth” world, where photographed people are real only to the extent they conform to our imaginations. The image world it gives us is of strangers-as-passersby who never make eye contact. It’s hard to see, really see, someone else in this world of images, surrounded by people who are all doing the same.

Views: 1017

It would seem to me that his idea regarding subjectivity is quite mistaken. In other words, subjectivity lives on both sides of the image – unavoidably so; it’s inescapably there in the mind of the photographer as again in that of the viewer. The trick, rather, would be delivering some deeper objectivity from either shooter or viewer.

Looking at the thing from your writing of it, and during the reading of it, it’s absolutely convincing if one is willing to surrender to that belief; perhaps I am failing to understand your point, but I am far from convinced immediately I finish reading and am able to come out from the state of suspended criticism and analyse for myself. Come to think of it, you have written a most convincing piece of commercial propaganda for Baudelaire’s beliefs!

In mitigation, it might be argued that the photography possible back then wasn’t open to employment of techniques that are commonplace today. There is a sort of stiffness that creates a certain period feel to early works that doesn’t happen with contemporary equipment and styles; in fact, the difficulty in getting pictures that have a period look that works well, is perhaps why not a lot of photographers has managed to get to grips with the Sarah Moon and Deborah Turbeville ethics: they require a particular mindset, its terms of references and, most importantly, access to locations that lend themselves to the genre. Photographers have to have at least some degree of reality before them in order to recreate it as their own.

Location photography has always been my own preferred modus operandi, perhaps because I quickly got bored with so much studio shooting against white Colorama rolls. Locations give you something to play off from, and help break the working relationship ice that cripples some studio sessions, especially when the people there have had no prior exposure to one another. That freedom comes with small cameras, the ability quickly to swap around positions and encourage change – or even continuity within some vibe that’s working – as you both (photographer and subject) do your thing. Stuck with head supports etc. ain’t gonna cut it too well! So really, I guess Baudelaire’s thinking was based on the stiff kind of photography he knew, rather than on photography as the very flexible creature – within bounds – that it’s become. He just lived too soon to know and see enough photographic styles; had he had that option, he might have had a whole different set of beliefs.

Rob

Perhaps it can be deconstructed as follows, Rob:

Photography freezes the two fundamental a-priori contexts: both the spatial context as well as the temporal context. The representation and freezing of spatial context may be less of a concern as it is usually still partially available. However, the freezing of time, both short term and long term, is a valid concern because a picture, specifically portrait, will never tell us how the situation or person became to be as depicted.

And that perhaps is therefore the primary obligation and concern of the photographer: to capture a story in the image. Otherwise one likely ends up with a lot of instagram postcard type images with precious little substance.

I agree: a still picture outwith a series can’t tell us the why of the situation. So yet again it has proven to be a subjective decision to go for that decisive moment, if you like.

Objectivity is very difficult to attain in any medium that involves human interference. You just have to think of Brexit to see lack of objectivity in all its glory. You’d be forgiven for thinking such a matter could easily be weighed up in logical, objective manner and common sense rule, but people can’t handle too much objectivity.

So no wonder Baudelaire’s plea for some subjectivity seems misplaced; there’s precious little else!

Yes I think you are right Rob, Baudelaire was making his mad assertions before he knew enough to blether.

Just like some people do over Brexit.

“Come to think of it, you have written a most convincing piece of commercial propaganda for Baudelaire’s beliefs”

That is my intent. i typically believe very little of what I write. I write it just so we can think about it.

It works!

Photographic truth can only exist within the camera at the very instant when it records an image of a static moment in a dynamic world. Otherwise, human imagination manipulates either the image itself, our perception of it, or both. Baudelaire was copping an attitude for Nadar’s lens just as we moderns pose for Instagram. It’s all in our heads.

But Lee, even that shot you describe isn’t capable of revealing a specific truth: it reveals an image made at a moment, but that moment is itself part of a flow and frozen in a camera it simply shows itself and not the reason, the truth behind the visible but frozen moment. Truth has to be part of something else or it doesn’t have either truth or non-truth to its claim.

To explain by example: considef a photograph of a person standing on a cliff edge and another person has his hand at that person’s shoulder. What is the truth? Is the second person just expressing love, pushing the person over the edge or pulling that person back from it? Without that information there is no truth, only ambiguity.

What was the other photo he was carrying?

Now that’s thinking out of the box, the road less travelled!

It’s a good question, Kenneth. Let me get back to you…

On my way home yesterday afternoon, I happened to hear a public radio interview with author Myla Goldberg about her new book “Feast Your Eyes”, which depicts the life and work of a fictional New York City street photographer…

https://www.npr.org/2019/04/25/716886442/real-photos-inspire-a-fictional-life-in-feast-your-eyes

The book is designed to resemble an exhibition catalog for a posthumous photo retrospective. The twist is that there are no actual photographs included in the catalog…only their detailed descriptions. For the author, this approach allows her to draw narrative inspiration from the works of people like Diane Arbus, Garry Winogrand and Vivian Maier without having to pay any royalties or fees.

As for me, I was struck by the realization that a physical photograph may very well evoke a storyline, but we can then close our eyes and continue the drama in the theatre of the mind without much further need for the photograph itself. Is this not Baudelaire’s “embodied vision”?

Thanks for the link, Lee.

Do you ever get the feeling that photographers are now fair game for rape on every single aspect of their work?

I so wish some living photographer – with the means – could identify his photo from the writing in that book and sue the pants off that writer.

Take, take, take… give nothing back.

A wonderful piece of writing, thank you, especially as I have a well-read copy of Les Fleurs du Mal, and would not have made this link.

<>

Is the drive to want, to possess, to create the new, “capitalist” or just human?

If we lived in the perfect communist world, and photography was introduced, would we inevitably become capitalists?

A timeline of pictures showing photographic technical quality from Daguerre to today would show the same increasing technical sophistication we see in every other field. We, as a species, are obsessed with technical perfection.

I look at my Leica and the accompanying invoice with wonder and suspicion.

JR