Leica started out as maker of small, simple cameras. If you needed a small, exceptionally well designed and made 35mm film camera, they offered you the tool. Any elitism that accompanied the Leica camera was a result of its status as the best built, most robust, and simplest photographic solution. You paid for the quality Leica embodied.

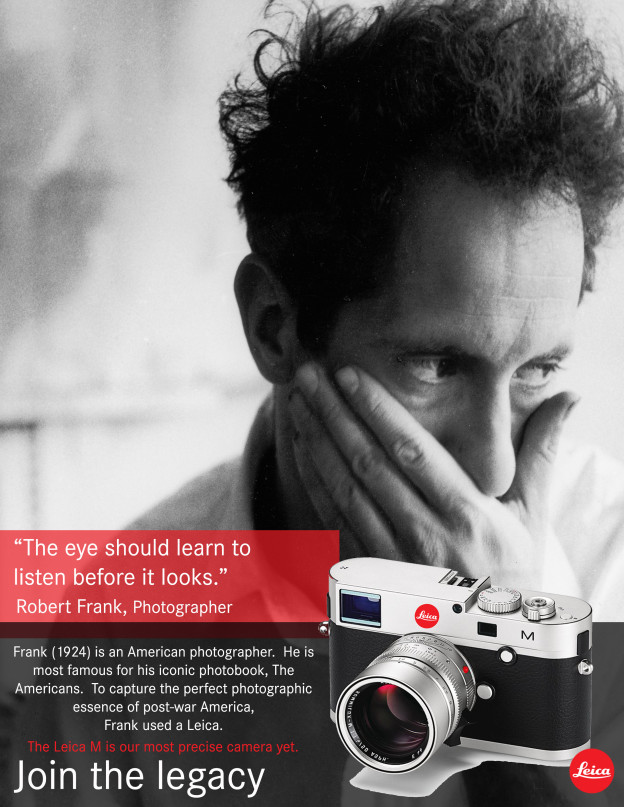

Over time, as technology trends accelerated and Japanese manufacturers like Nikon and Canon grabbed the professional market, Leica shifted gears, no longer competing on whether or not their rangefinder cameras were the most useful or most efficient tools for a given purpose, although, for certain limited purposes – simplicity, quietness, discreteness, build quality – they remained exceptional as tools. Starting with the digital age, Leica now competed primarily on luxury, which is a fundamentally different promise than the optimal design of a tool.

Leica is now a luxury tools company. The cameras they sell cost more, but some photographers still choose them, some for the identity that comes along with the use of a luxury good and some for the placebo effect of thinking one’s photographs will improve by virtue of some special quality it is assumed Leica possess. But there remain some of us who still use Leicas because a Leica rangefinder is still the most functional tool for us in the limited ways they always were. We still identify with Leica not a a luxury good but primarily as a maker of exceptional tools, and this creates the ambivalence many of use feel towards the brand as currently incarnated. The ambivalence is a result of the tension of a Leica as a tool versus a luxury item.

Its a tension that Leica is having a difficult time navigating too. As a luxury item producer, Leica probably doesn’t care that its cameras aren’t cutting edge. On the other hand, Leica knows it will not survive if its product is not seen as a preferred choice of the status conscious. At some point in the evolution of every luxury branded tool, users who care more about tools than about luxury shift away to more functional options. You see this today in Leica purchasers’ demographics; the brand is perpetuated largely by those who identify a Leica as a status marker, whether that Leica be a used M purchased on Ebay by someone come of age in the digital era who wants to The Leica Experience, or a new digital M purchased largely by an affluent amateur. Professionals and serious amateurs who need the services of a small, discreet camera system have largely migrated to more sophisticated, less expensive options like the cameras Fuji is currently offering.

I suspect that the era of Leica as a working tool is gone, but the silver lining is that there remains a small but dedicated following who values mechanical Leica film cameras still as a functioning tool, and hopefully there will remain those who cater to them and service them. It would be a shame if that portion of Leica’s heritage were to be lost.

Views: 641