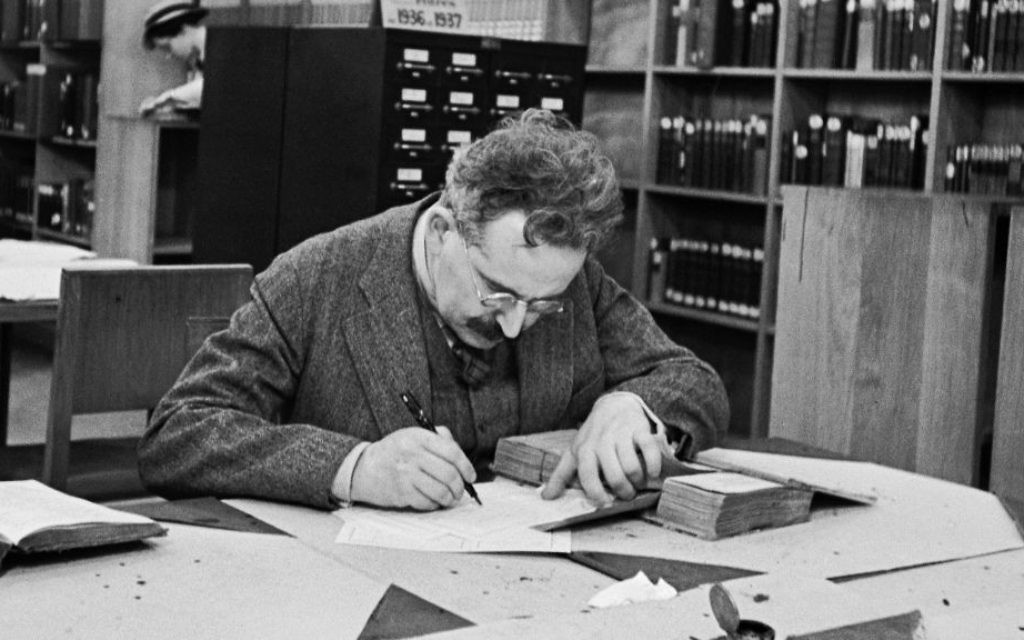

The German philosopher Walter Benjamin overturned the by now anachronistic conception of Charles Baudelaire, who divided art into two opposing camps : on the one hand the imaginative ( true artists who want to “illuminate things” with their subjectivity) and on the other hand realists (who want to “represent things as they are” but have no real means to do so). Benjamin’s essays – Little History of Photography in 1931 and, more importantly, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction in 1936 – argued that photography had finally emancipated art from the imaginative dimension that he claimed had heretofore characterized all traditional artistic work, and as such was a watershed historical moment in the history of imagery production.

Even in the era of prevailing subjective pictorialism forward looking photographers took up Benjamin’s call for realism, seeing in photography a unique medium to approach and recreate the truth for other’s purview. Among these, in America, were Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine who used photography as a tool for social investigation and denunciation. In France Eugene Atget documented a disappearing Paris.

In America, Jacob Riis fathered modern social investigative photography. Emigrated from Denmark, he initially worked as a police reporter, but then devoted himself to photographing the most disadvantaged areas of New York. In 1890 he published his book How the Other Half Lives: Studies on New York Tenements ,where he documented the life of immigrants in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, then the most densely populated area of the world, with over half a million people in one square kilometer. Riis’s work spurred New York Governor Theodore Roosevelt to take government action to alleviate the retched social conditions Reis met there, and as such is remembered as one of the most influential photojournalists who documented the social injustices of America between the end of the 1800s and the beginning of the 1900s.

Lewis Hine, a teacher at the Ethical School in New York, used photography as a sociologist, photographing the life of immigrants on Ellis Island. In 1908 Hine became an official photographer of the National Child Labor Committee , an organization created to combat child labor in heavy industry. There he used photography as an instrument of social protest, accurately representing child laborers and their working conditions.

*************

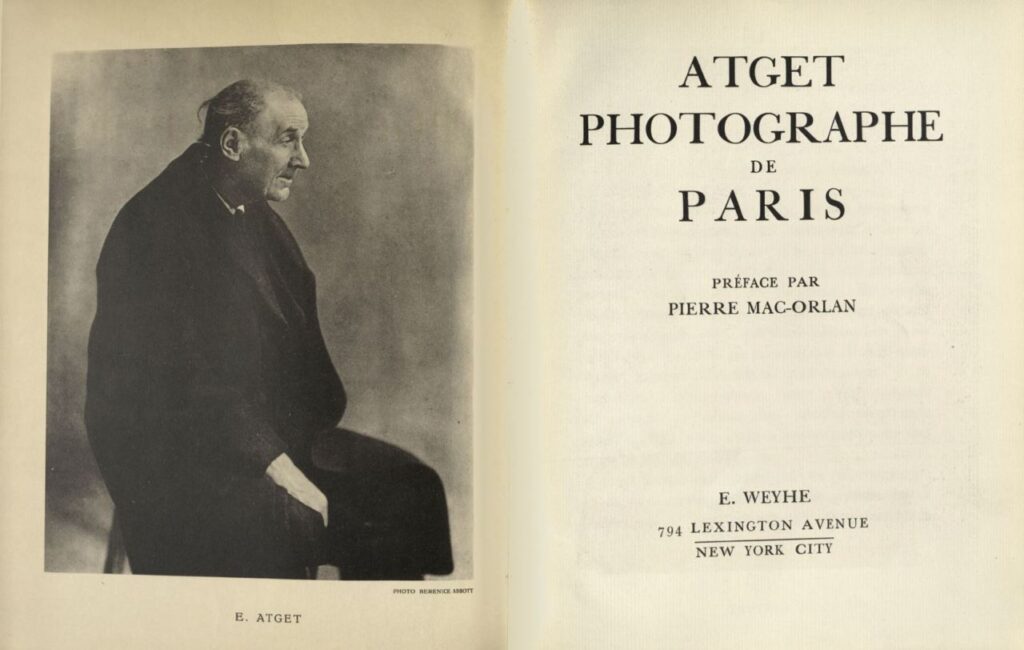

From 1889 to 1924 Eugene Atget documented old Paris, which was transforming itself into a modern metropolis, “manifesting from the outset the ambition to create a collection of all that is artistic in and around Paris”. He considered himself a commercial photographer, so much so that in 1890 he exhibited a small plaque outside his laboratory with the inscription “Documents for artists”. With his 18×24 bellows camera, a heavy wooden tripod he systematically photographed Paris, its architecture, shops and shop windows, along the way garnering the interest of the Surrealists like Man Ray and Brassaï, who saw in Atget a surrealist approach (i.e. highlighting and magnifying the real).

Atget died relatively unknown in 1927, although some of his prints were present in various archives in Paris. Atget’s artistic recognition was posthumous, thanks to the interest of Berenice Abbott ,who after Atget’s death bought the collection of Atget’s negatives and prints. These are now housed in the Museum of Modern Art in New York. In 1930, Abbott published the first book of Atget photographs, Atget, Photographe de Paris. From this moment his fame grew, so much so that he is consecrated as one of the most influential photographers of the early modern age: appreciated and recognized both by ‘realist’ American photographers such as Walker Evans, Ansel Margaret Bourke-White and by Europeans André Kertesz , Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Frank and Josef Koudelka.

*************

Why the new use of photography as practiced by these men and their successors Cartier Bresson, Walker Evans, Robert Frank, Josef Koudelka? As Benjamin noted, as a means of mechanical reproduction of nature, the photographic process removed the necessary subjectivity inherent in previous ‘artistic’ approaches to creating imagery, which by its very nature relied on the artist’s subjectivity to render. With a camera, that subjectivity was nullified; the camera recorded what it recorded (of course this doesn’t account for the fact that someone has to point the camera at something). What we’re given is an objective view, using Sontag’s words, “stenciled from the real.” While photographers may editorialize to the extent they choose certain subjects and present them in certain ways, photography’s objectivity assures us that what we’re seeing is real, it happened, and as a result we can draw various conclusions about the state of affairs it represents.

Is this type of photography still available to us in the digital age? I’d argue it isn’t, and this is one of the enduring conundrums photography must face as it goes forward. Photography is no longer mechanical reproduction, which Benjamin saw as the means by which it achieved its claim to objectivity. Ironically, Benjamin anticipated this devolution back to subjective imagery. In his view, history was not a linear story of progress where we learn from the past, but rather something chaotic and contradictory in which past mistakes are repeated by future generations. Digital technology has made photography endlessly maleable and as such has brought it back to the subjective status Benjamin identified as the defining characteristic of pre-photographic imagery. The objective link has been severed. If you use Benjamin’s criterion of truth, photography as an objective chronicle of the truth is dead.

.

Views: 601

Did someone say dog walking with a camera???

There must be an echo in here……

Erwin Puts was saying this nearly 20 years’ ago. I didn’t want to belive it then, but I think he was right:

“The mental state of the photographer then has to be totally different. The famous pre-visualisation of Ansel Adams and the importance of having a photographers eye in order to see the scene photographically are redundant. The switch from a filmbased camera to a digital camera is a fundamental change in the mental state of the photographer and style of picture taking…

…The basic act of a digital photographer is this and you can observe it everywhere on this globe: the photographer looks not through the viewfinder but at the display, takes the picture and waits to examine the result ….”

Photography is silver halide based and it is still going …as long as we can shot film (or collodion) and wet print. Digital isn’t photography, it is computerised imaging. As Neitzsche observed about 19th century Europe in which God had died ….it takes a while for people to notice.

Gavin: Yes, we still have “photography” in the sense that we can still shoot film and follow the old methods, and in so doing buttress our claims to objectivity. The problem even then is the presence of digital – I can tell you it’s film and therefore has some inherent truth value, but you can always reply “How do I know it’s film? It may be a digital file you’ve run through emulation software. Who knows?”

I can’t prove to someone else that my print isn’t a digital one but I know it’s from a negative. What digital has done is send me over wholly to black and white and to printing in the darkroom and doing it myself instead of handing it over to a lab. I just can’t get interested in the digital process at all, but then I am just taking photos for my own pleasure; it isn’t a job. As for realism, I am not so bothered about the indexical nature of a photo now. Much more interested in atmosphere and suggestion and the penumbra of the half seen.

Even though they are easily manipulated and edited, it seems to me that personal cellphone videos, transmitted casually via Twitter etc, have replaced the still photograph as our mirror of ‘reality’.

Twitter etc. are the beginning of the end of what was once thought of as truthfulness in the dissemination of information.

The traditional, pre-digital media had to conform with basic standards, much as advertising was meant to do. What was printed in a book, magazine or newspaper was there as testimony, forever, or at least until all the paper rotted. If one of those outlets lied, printed something untrue, it couldn’t just vanish everything and hold up its hands in mock innocence; the printed proof was there, could be presented in court.

Look at the way that the social media platforms have been used to propagate political lies, to persuade the gullible that whatever some rich politician says is true. Hell, it has even been used to attempt revolution in current America. The only hope will be in the abolishing of all such digital platforms of mass communication, or at the very least, of visible policing of them all. If not that, then better forms of ensuring that people are who they say they are must be introduced. I would start by making it illegal to post anything on social media without full disclosure of identity. That would at once make many people think carefully about what they post.

Apart from anything else, think of the massive energy footprint of keeping all those platforms alight. I have got on perfectly all right so far without having tweeted or facebooked even once. They fill me with horror, those concepts. There are many wonderful things that digital can do; opening the gates to every nutter in the world to spread his insanity is not one of them.

Of course, there is always the other side of that coin: those same platforms can also be tools in the fight against tyranny. I’m sure Iranian authorities have their eyes on that one, as has every despot around the world. I guess society will have to come to a final conclusion on that, decide whether total freedom is always the best thing or not. I’m not holding my breath.

I dunno. I think all photography, whether on film or on a solid state light gathering device, is at most a stylized version of reality. It’s all manipulative. Film photography is just as “unreal” as digital photography.

You spent the better part of the last blog entry saying this very thing.

We don’t see the way the camera sees. It is sur-realism.

Moriyama famously said his camera was a copy machine. He considers his work, all of it, full of grainy, blurry, out of focus goodness – are-bure-boke – to be copies of reality. But not “accurate”, nor “objective”.

Certainly all photography is interpretive i.e. a stylized version as you say. The difference is its relationship to the thing out there; one is an interpretation of a real thing; the other may not be. That’s the distinction.

While I agree almost entirely with you, at the highest level I think photography, whether digital or analog, still affects policy or world events. You give us several examples from the past, Riis and Hine affected the living conditions of individuals, Atget influenced photojournalists in showing things as they are.

I don’t think this process has finished. We can still point to individual photographs that changed the direction of events. Starting in the film era Nick Ut’s photograph of Kim Phuc running from a Napalm strike affected the course of the war and it’s veracity was initially doubted by Nixon, and Ron Haviv’s photo of Panamanian VP Guillermo Ford under attack affected the decision to invade Panama.

We just need to be less gullible in the age of digital prints. But photographs from photojournalists such as Lynsey Addario and Ashley Gilbertson to name a couple are no less believable or influential because they work with digital cameras. Addario’s photos on potential war crimes in Ukraine are not less important because she’s using Nikon DSLR and mirrorless cameras or Gilbertson’s work on militarization of the South China sea because he’s using Fujifilm digital cameras.

In some areas manipulated photos are still a cause for scandal, when we are trying to establish the facts of what happened. It’s when every sunset is put through the warming filter, or every model photo has the legs lengthened and body mass shifted around that you begin to ask is anything real anymore.

“or every model photo has the legs lengthened and body mass shifted around that you begin to ask is anything real anymore.”

That started well before Photoshop and digital: think bra. Sometimes, the removal of is the biggest letdown any young man has ever faced. Salutary life lessons are learned.

Life was much more honest in the 60s and 70s, and on many European beaches. I think you can thank the French for starting the latter summer campaign for truth and naked reality. 😉