Having just sent off a 50’s era Leotax to a good man and dedicated Aussie Leicaphilia reader who seems to have a fetish for my cameras (I’ve probably sold him 10 along the way, including (I think) a cherry Hexar RF that I regret selling every day of my life (are you reading this, Rei?)), I’m now down to one film camera (not counting my 3 wooden pinhole cameras), a cherry Nikon F5 that you’d be hard pressed to find any evidence of hard usage. It’s a beauty. In a brief interlude of irrationality, thinking I was probably dying in a week or two (bad week) I actually put it up for sale here on the site for $255/shipped, but nobody wanted it ( I did receive on inquiry from some cretin mocking the price ( Q:”$255 for a Nikon F5?????” A: “Yes, Asshole, $255 for a Nikon F5. Can you not read?”). In hindsight, I’m glad none of you wanted it, first I’m still alive and paradoxically feeling better every day (I’m going out for a full day of motorcycle hooliganism tomorrow, a day that promises to be 70 degrees and cloudlessly sunny) because you’d have been getting a really nice camera worth more than you paid for it, and, more importantly, I get to keep it.

My love of the F5 is more theoretical than practical. No doubt its a beautiful beast of a thing that works flawlessly and represents the high-point of the Nikon F professional camera evolution and in that respect alone should be considered a classis. The F6, while possibly being a marginally better camera, wasn’t built for professional use but was a vanity project, to be bought and left in the box with an eye toward value appreciation. The F5 is the ultimate working camera; I suspect there’s more than one working journalist who’s had theirs run over by an Abrams tank or dropped out of a helicopter on some clandestine military mission only to find it working perfectly after they hosed it off and gave it a good spray of WD40.

Granted, my love of the F5 is a product of pure camera fetish wonkery, the kind I so mercilessly mock in others (consistency, as my wife reminds me, is not one of my strong points. So what). While living in Paris in 03 I’d spent time an inordinate amount of time in the camera shops on Beaumarche ogling the latest offerings, where one I frequented had a huge Nikon advert for the F5 strategically placed at eye level behind the counter. It promised me photographic nirvana, an end to my ceaseless cravings for the camera that would finally meet my practical, emotional and psychological needs. So, when I got home to the USA I bought one. It’s a beauty…but I never much used it, using it not being the point. But I digress.

*************

A year ago I had more film cameras than I knew what to do with: in addition to said F5, an M5 (sold), a Nikon s200 with a bunch of pretty lenses (sold), a Nikon F100 (we’ll get to that later), [Editor’s Note: Oh yeah, I forgot about that wonderfully patinaed plain- prismed black Nikon F], a beautiful black paint Canon VT with two beautiful rare Canon era-specific lenses (sold), an M4 (sold), a Leicaflex SL (sold), a gorgeous Leica IIIg with Leicavit (sold) the Leotax (given away as repayment for a previous act of generosity by the givee), and Pentax K1000 (given away) (everybody needs at least on K1000). I also had a dedicated film freezer stocked with more film I could shoot had I been lucky enough to live till I was 90. That’s all gone too now, victim to friends who took me up on my offer to “take anything you want” back when I was sitting in my hospital approved bed leaking bodily fluids and, given my 5 day till death prognosis, having a mind-altering pre-funeral bash with 20 of my best friends.

After everyone got sick of waiting for me to finally die, and me stubbornly not complying, they all eventually went home, at which time I found my F100, my iconic Nikon F, most of my manual focus Nikkors, and almost all of my bulk film shamelessly looted. Someone even took my bulk film loader and all of my reusable Kodak snap-on cassettes. No that I cared, and they weren’t “looted” except to the extent that massive ingestion of oxycodone, liquid morphine, innumerable snifters of Calvados and bourbon with an occasional psychotropic gummy thrown in for good measure while Led Zep’s Black Dog played on a loop in the background and my dog Buddy snuggled somewhat confused next to me on the bed, may have compromised my ability to consent to such ownership transfers. Frankly, who cares, plus I owe the guy who took off with most of it more than I can ever repay – a wonderful friend who’d give me the shirt off his back and has on more than one occasion. An old F, an F100, an bunch of lenses and some film is a small down payment on the massive debt I owe the man for being in my life.

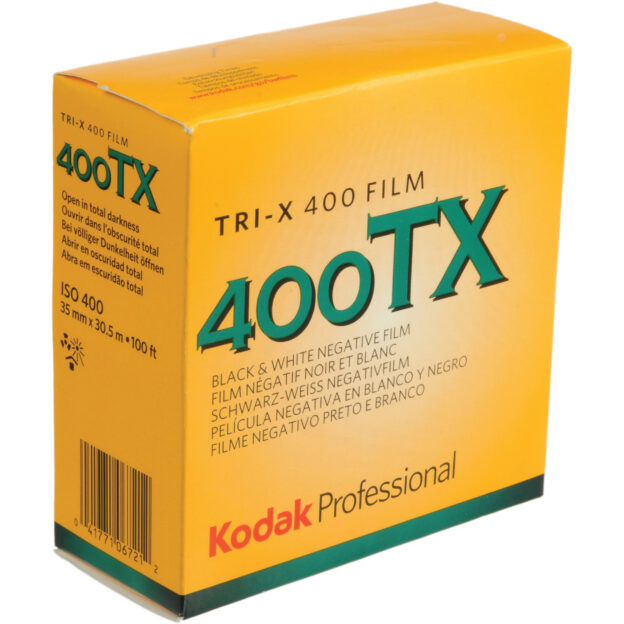

I’m now left with my F5. It sit’s next to me here in my study, beseeching me to do something with it before it’s too late. I believe the universe is trying to tell me something. So, suppose I’m going to have to comply. To that end, I’ve bought another bulk film loader, a carton of 10 Kodak film cassettes, and a 100 ft roll of Fomapan 400, a relatively inexpensive Czech film that gives a nice gritty look when shot at 800 and developed in Diafine. (I now develop everything in Diafine. It’s magic) I’m now officially a film photographer again. Here’s hoping I get enough time to use it.

I aspire to be like this guy below:

************

So, now what? As noted in previous posts, I’m now a Raleigh flaneur, prowling the immediate neighborhood for interesting stuff to photograph, which in reality means taking a lot of photographs of 1) religious iconography 2) my shadow (a great underutilized photographic resource and 3) religious iconography that includes my shadow. And I’m going to be doing it with film, wonderful, obsolete film along with an equally kick-ass Nikon F5. Hell, I’m even thinking about buying a brand new, straight from the factory Leica M6. Why not? I deserve it. When I’m dead my wife can sell it to one of you readers. That’s the least you can do for me, right?

Of course, I reserve the right to also take out my latest affectation, the Sigma SD15. Maybe I can do a few comparison posts – Sigma Foveon vs. Fomapan 400.

Views: 437