“Silence is the hidden content of the words that count.” A.G Sertillanges

I’m suspicious of critics who write about photography as an art form. I don’t think I’ve ever read a critical essay about a specific photograph or body of photographs that has in any sense added to, or explained, the experience given by the photograph itself. This is not to say that there isn’t good writing about photography. There is. Sontag and Barthes come to mind, but what they are doing is writing about photography as a practice and not attempting to explain or supplement the truth of specific photos. Reason, as expressed in language, can not articulate visual truths. Reason’s last step, according to Blaise Pascal, is to recognize its limitations.

For that matter, photographers who attempt to explain their work via written captions or accompanying essays seem to me to be missing the very point of visual art itself: visual art expresses that which can’t be expressed with words. To use a metaphor of the great German philosopher Immanuel Kant, words are a net we strain reality through. A lot gets through the net. What the visual arts offer us is a portion of that reality that gets through the net of language.

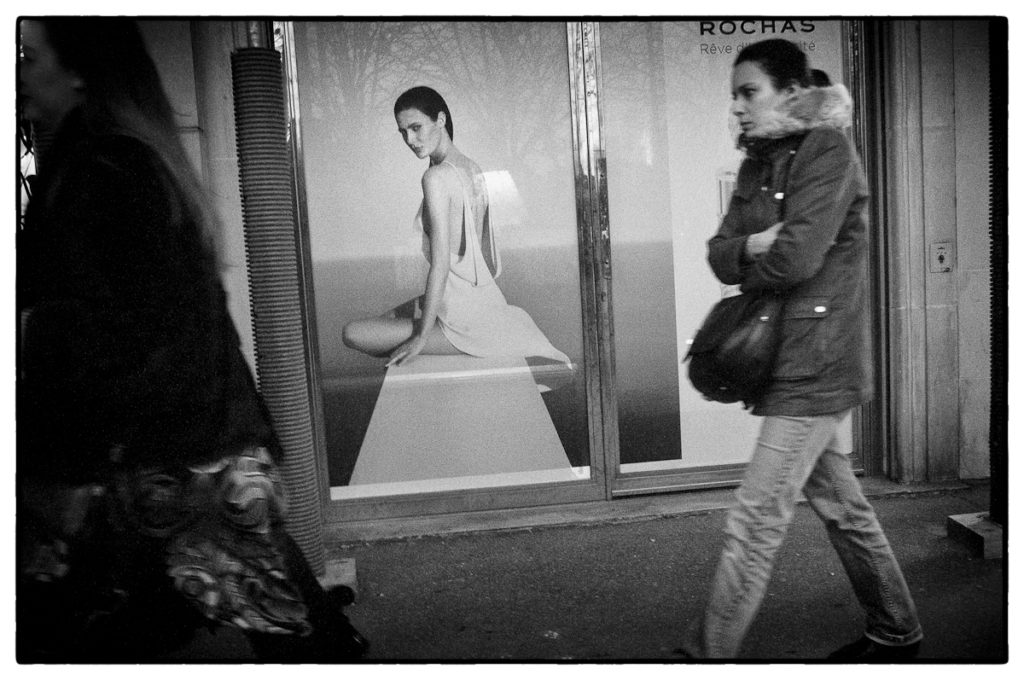

This, I think, is the power of photography and why many of us are drawn to it in a very profound way. It’s a means of expressing things that can’t be expressed verbally. The photograph above is an example. I found it on a roll of film I recently developed. I don’t now remember its specifics – why the took it, what I saw in it, if anything at the time – but now, as a finished product standing by itself, it denotes something to me. It presents something visible to me, something that resonates with me. Whatever it is, it’s not capable of being put into words. It represents that portion of reality Kant would say has slipped through the net of language.

*************

Ludwig Wittgenstein remarked on the human urge to “run up against the limits of language.” We instinctively understand that words somehow deaden the fullness of our experiences. According to Isaiah Berlin, this is the paradox of language when faced with profundity: “the more I say the more remains to be said … as soon as I speak it becomes quite clear that, no matter how long I speak, new chasms open. No matter what I say I always have to leave three dots at the end. Whatever description I give always opens the doors to something further, something even darker, perhaps, but certainly something which is in principle incapable of being reduced to precise, clear, verifiable, objective prose.”

German philosopher Martin Heidegger agrees with Wittgenstein and Berlin…up to a point. Much of Heidegger’s philosophy is about limits, of knowledge, of words, of expression. For Heidegger, logical thought -i.e. that which can be expressed – is not sufficient when we’re trying to talk about certain things. “The very idea of “logic” disintegrates in the vortex of a more original questioning,” wrote Heidegger. Wittgenstein, Berlin and Heidegger all agree there is more of life than can be articulated. Heidegger, however, makes the further claim that what happens in the interstices between words is what’s really important. This is where we find the most profound truths. For Heidegger, this is a qualitative advance on what Kant was saying. Kant (and Wittgenstein and Berlin) was saying that some reality slips past the net of language. Heidegger is claiming that the most important part of reality slips through the net.

So, how do we communicate this most important portion of the real? Heidegger attempted to do so via language. This is the paradox of Heidegger and the reason he’s so hard to understand. He is attempting, with words, to express the truth that words miss the larger truth. This is purposeful. Heidegger holds that we should try to say something about the interstices – that the fact that we recognize an interstice means that there’s something to be said about it, however vague and preliminary that might be. Not directly, perhaps, and not even particularly clearly, but we shouldn’t abandon all efforts to use words to speak about things that lie beyond language. Unfortunately, Heidegger never took the next logical step of analyzing the visual arts and what role they might play in the process of expressing what’s true. I believe he might have found a way out of his expressive paradox had he done so.

Views: 90

Welcome back into your own spot. What kept you – life?

Captions. Indeed, and sometimes they seem quite appropriate and legitimate. Taking a definitive kind of stance in either direction seems a bit off: some people enjoy writing them, thus getting a further buzz out of their pix.

It’s not even certain that viewers all take the same message home with them on the matter. For instance, when I produced my first Hewden/Stuart calendar back in the 70s, I hit upon the idea of using several images on each page, a main one and also a little cluster of two or three small ones; there was also a little line of copy vaguely connected to the photographs. For the next one, I suggested leaving out the words and just having the photos. The client was most upset: oh no, he said, I have no idea what you are writing about, but I like it! Go figure. I stuck with captions for the duration of the relationship.

Perhaps the trouble starts with humour. It can be quite a pleasing addition when it works, and an embarrassment when if falls on its face. Snag is, even that decision or interpretation can depend on the reader’s state of mind at the time. I’ve felt both ways about much of my captioning. Yes, the safe way would be to write nothing, but then that precludes the fact that the photographer often does have an idea in his mind when he shoots his stuff, and words simply confirm the direction of his intent. Why would he want to deny himself that? Indeed, many of my pix have a genesis in a line that came into my head at some time. Not all photos are the result of a moment’s brief passion, lost and unloved waifs standing forlorn on a railway platform.

On the other hand, from the example of your three pictures, I’m kinda glad there are no captions: I like to formulate my own interpretations. But then neither you nor I are photographic neophytes: we come at it from a different starting point. I think that’s an important distinction in such matters.

Thanks for making Sunday night a less boring place to be.

Rob

Around ten or fifteen years back I read a book by a Danish writer; Peter Høeg, called Miss Smilla’s Feeling for Snow. It was OK and representative of its genre. One of the characteristics of the eponymous heroine was an (apparently common amongst her compatriots) ability to describe snow with at least 45 different words, all meaning something slightly different.

I expect it is a bit like that ’round your manor Tim, only the subject is wind.

Hope you are all safe and well?

Which is a bit like the thrust of your article…

“A picture is worth a thousand words…”

Which is only fair… we saw, well before we read.

“I expect it is a bit like that ’round your manor Tim, only the subject is wind.”

I can always count on you, Stephen, for a back-handed compliment.

I am sorry Tim, I think that you might have lost something in translation… They say that Americans and Brits are common folk only separated by language…

So no compliment, rather an enquiry after your presumed escape from the weather you were offline for a while?

“(around) ’round your manor” means…. in your back yard, your town, your locale… etc..

I noticed that NC has just been subjected to a (depending on which videos you look at) bit of a windy night. Looking at the various online weather reports, nobody could make up their minds whether it was a “tropical storm” or a “hurricane”.

Your governor just said whatever it is called, it is dangerous…. stay in!

In other material a bloke in a blue oilskin is screaming into his mike as he is lashed by the wind and rain.

Sorry, the analogy was a bit obvious.

No need to apologize,Stephen. I will admit to being a bit windy myself, which is what I thought you were referring to.

Outside of photojournalism, a still picture taken for wordless reasons needs no words to describe itself.

Hmmm… even if you know she loves you, it’s nice if she sometimes tells you.

🙂

I made things, almost always, that combine words and pictures. Perhaps the job of the pictures is to fill in the spaces between the words.

Certainly I quite dislike pictures as mere illustrations of the words.

Thing is, the idea, the juice of it exists in our minds. It’s neither solely child of eye, nor of emotion that can’t be articulated on page and not even in lengthy conversation with oneself; it’s an entity born from our general experiences and sense of reality and/or perception.

I believe that those moments of emotional awareness are perhaps easier to feel – and at a stetch, to understand – when expressed through a version of shorthand that converses with the senses in a non-specific fashion. A camera offers that, as do poetry and music. In other words, we understand the hint if not the fine print of the exchange. Hence, it’s important to know if the idea came before the photograph as in pre-planned, or was an almost instantaneous reaction to something that just fitted the moment. And would the seen moment have had an impact, meant anything, had it not prompted us to photograph it? In other words, does the act of photographing it perhaps actually manfacture it, provide it with a birth certificate of sorts?

Perhaps the question mightr be: is it better to employ a caption in order to focus on, clarify a little one’s own emotions, or should we leave them aside and let the viewer either feel or not feel anything depending on his own general awareness? Which inevitably returns us to the point where we have to consider for whom the image has been made and for whose benefit it’s on display.

I think that part of the confusion stems from the fact that a lot of those people writing their essays on photography aren’t actually photographers. At best they may be happy snappers, in which case they never truly experience what it is that drives photographers to do what they do, embrace photography to the extent that it becomes their way of life. Sontag only got her final insight by living with a prominent photographer; how well did that qualify her to write with authority before or after? I met my wife when she was at school with me; we even worked together in the business after a while, but did that mean that I understood everything that motivated her? Hell no! I know she would have fought to the death to protect our kids, but what she thought about photography I shall never know. Frankly, I don’t think she liked it very much, and especially did she not like the business that went with it, the duplicity, the scams one tried to avoid and the regular empty promises.

Which of course, returns me to what you expressed: “This is not to say that there isn’t good writing about photography. There is. Sontag and Barthes come to mind, but what they are doing is writing about photography as a practice and not attempting to explain or supplement the truth of specific photos.” Maybe the closest I can come to describing accurately the meaning of a photograph is to say that collectively, those many different moments of meaning gave meaning to my own existence. Had I followed along my first reluctant steps and gone on to complete them and become an engineer, I believe I’d have taken myself out decades ago. Or it would have done the job for me.

I’m at the “Limits of Language” with this one.

https://www.dpreview.com/news/1945647466/these-copper-plated-leica-cameras-manage-to-make-even-broken-rangefinders-expensive

As Oscar might have said:

The unspeakable in pursuit of the unusable…

As the author rather understated: The result speaks for itself.

I wonder what Mr. Vonnegut would say, apart from “and so it goes”?

Look on the bright side (pun, etc.): one would never again need to buy a California Sunbounce.

😉

P.S.

Seems that Tim doesn’t want any responses to the Nikon Rangefnder articlette. Ain’t neologgin’ fun?

“…all the other nonsense we feel necessary to value when we fail to acknowledge the poverty of our vision.”

I realise this ain’t the thread for the above – it isn’t permitted a thread – but that comment above in the article about Leica killing Leica photography is so accurate across photography that I felt obliged to underscore it wherever I reasonably could.

Rob

“How to become a photographer” really is asking for comment; good advice, but the most broadly relevant part of it was, I believe, where he suggests that the youngster to himself be true. What else can anyone do to avoid a life of plagiarism? And even where not intentional, external influences are so terribly powerful that it’s practically impossible to remain virginal, original and with the nose held close to one’s private furrow. Bring in business, and you haven’t a chance.

Anyway, if you want to be a photographer as distinct from a jobbing photographer, the question of how to become one shouldn’t even raise its head – it’s self-evident: get a camera and go snapping. Why do people want others to tell them how to think? It’s not healthy. Certainly, ask all you can about the mechanics/electronics, but leave the substance up to yourself.

Rob

I really enjoyed the interweaving of ideas about lthe philosophy of language and photography. Especially the comment on artists talking about their work. This rings true across the canon of art (Turner used to put poems beside his work).

Wittgenstein often pops up in ideas that try to show that in some cases that language is not enough. However, he actually means the opposite of what is being explored in your article. True enough people will talk and say very little (artists included) but for Wittgenstein understanding the use of language is more important than trying to make claims about its value. That was specifically his point about language, that focussing on where it begins or ends in terms of meaning will lead us to assume values on words beyond their use; which for Wittgenstein was the point.

Interesting link with Heidegger and Wittgenstein but I think the latter would held a view not dissimilar to Sartre if the two had actually met.