The Studium of This Photo: Roland Barthes in 1980. The Punctum (For Me) of This Photo: Shortly After, Barthes Got Run Over by a Laundry Truck

” Color is a coating applied later on to the original truth of the black and white photograph. ” That’s a great quote, maybe my favorite thing Barthes has written. Funny I don’t remember having seen it before, but there it is on page 81 of Richard Howard’s translation of Camera Lucida published by Hill and Wang. I ran across it while re-reading the book. The quote stuck out for me because it’s so quotable, the sort of pithy bon mot that fits great in an essay about  photography. And it’s by Barthes no less, so it’s got tons of “crit lit” street cred. You’d think others would have liked it and used it, and I’d have run across it numerous times in past readings, given I read a lot about photography. But no, I’ve never seen it before.

photography. And it’s by Barthes no less, so it’s got tons of “crit lit” street cred. You’d think others would have liked it and used it, and I’d have run across it numerous times in past readings, given I read a lot about photography. But no, I’ve never seen it before.

Which is further proof of what I’ve long suspected: All sorts of people – from academic ‘critical theorists’ to the pretentious no-hopers who congregate on photography websites – love to reference Barthes’ “seminal” work about photography, Camera Lucida, but few of them have actually read it. It’s the sort of book one must be conversant with when one is “serious” about photography, but in reality, nobody reads it. They just discuss it as if they had, with other serious people who haven’t read it either, repeating its fashionable jargon deliberately conceived to exclude those not in on their “discourse.”

*************

Some general background about Barthes: Barthes was/is a French literary theorist, philosopher, linguist, critic, and semiotician, a “post-modern” deconstructionist whose work has influenced structuralism, semiotics, social theory, design theory, anthropology, and post-structuralism. Suffice it to say that he was/is the poster boy for the French Post-Modernist Intellectual, a quasi-Marxist true believer in a Nietzschean relativism that holds there is no truth, no argument superior to any other argument (which, if you think about it, is completely contradictory on its face). I’ve written about him before here, which should tell you more than enough of what you need to know about Barthes.

So, assuming you haven’t read it, let me give you the Cliff Notes on Barthes’ Camera Lucida. It’s simple, and it’s this. What makes photography unique is the fact that it faithfully records the fact that something has been. Something was there, actually existed, reflected actual light rays, those light rays imprinted themselves on a film media, and the end result is an artifact – the photo – that possesses, in some significant sense, the essence, the being of that thing photographed. And this is the essence of photography as a representational medium.

*************

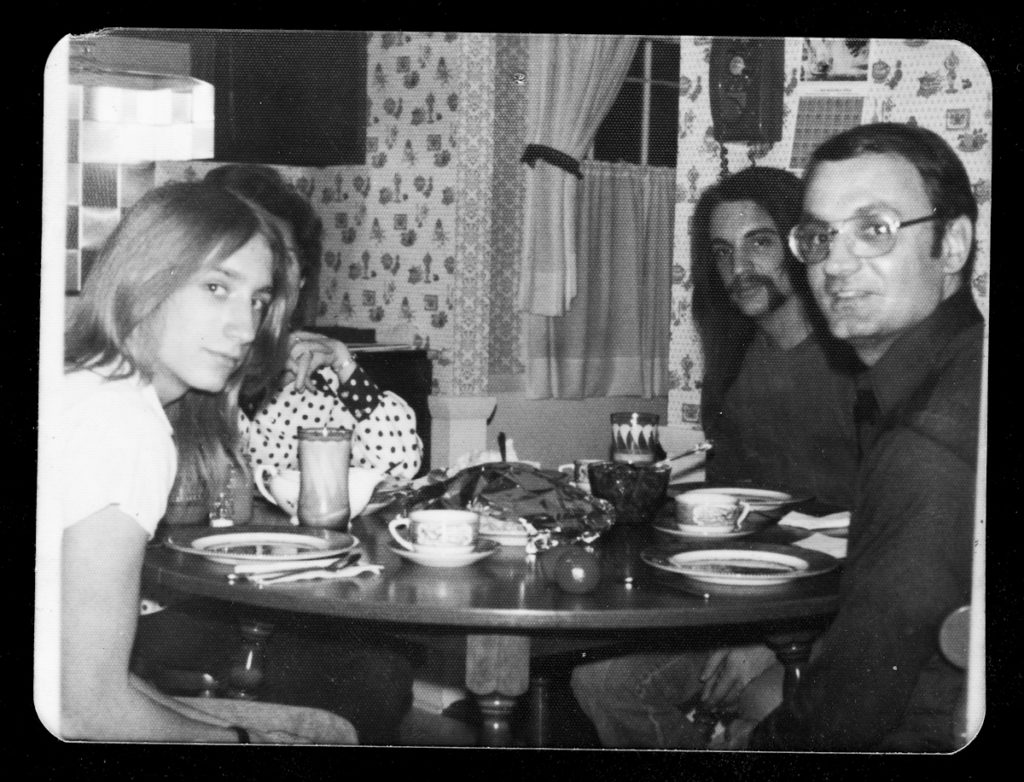

Wayne New Jersey, 1974. The Studium: Me, My Brother and My Dad. The Punctum: My Brother Looks Like Harry Shearer in Spinal Tap.

Barthes then goes on to analyze what makes some photography more arresting than others. This is where Barthes introduces the idea of the studium and punctum and the distinction between the two. Every photo has a studium. The studium is simply the subject of the photo – the thing, the person, the landscape etc. – the thing that was there in front of the camera, the thing the photograph describes. One thing we know about this studium is that it existed at the time the photograph was taken. We know this because photography has this indexical relationship with the real. By its very nature, photography deals with real things.

What differentiates photos from each other for the viewer is the presence or absence of the punctum, which is the emotional significance of the photograph for the viewer. The punctum is the viewer’s subjective response – something not there but merely hinted at- that jumps out of the picture at you, that says something to you over and above what simple definitional reading of the picture would imply (“that’s a picture of my mother”), that takes you out of the four corners of the photograph and transports you to a world outside of the photograph. That’s the punctum.

To illustrate the distinction, Barthes discusses a photo of his mother, the “Winter Garden” photo, a photo he has of her as a child, standing with her brother at five years of age, assuming a certain self-conscious pose, her fingers of one hand held awkwardly in the other. The punctum of the Winter Garden photo for Barthes is this: this photo leads him back to the realization that his Mother, now dead, existed, and she existed before Roland existed, and this photography contains some part of her. She stood in front of a camera, with her brother, wearing those clothes, and held her hand like that, light reflected off of her and stenciled itself onto the physical medium of the film. The photo is physical evidence of her presence, evidence stenciled directly off the real. To put it another way, the punctum of the Winter Garden photo for Barthes is his realization of the existential reality of this particular studium. Deep.

*************

The Studium: Semana Santa Easter Celebration in Valencia. The Punctum? Up to you.

The studium/punctum distinction is interesting, but it’s only marginally related to the book’s main point. You wouldn’t know it, however, by reading about the book in the usual echo-chamber. The studium/punctum distinction is secondary to a much larger and more important point Barthes is making: that what constitutes photography is its indexical relationship with what is real, what’s actually out there, and this relationship is unique among every other communicative media. Photographs, unique among other means of representation i.e. painting, writing or speaking, necessarily deal in the real and are evidence of the real. That’s the magic of it. While someone can manipulate an analog photograph to a certain extent, the exception proves the basic rule: photography, in the words of Susan Sontag, is the stenciling off of the real. Nothing else is, and that’s the value of photography and why it holds a special status as a communicative medium.

Think of it this way: A painter can paint something and present it to the viewer. What he’s painted may represent something that exists/existed, or it may represent something that does not exist, never has existed, a figment of his imagination or something he hasn’t seen. While he can claim it’s an accurate representation of the real, we can never know for sure. Likewise, a writer, using language as his device of representation, can write something purporting to be the truth about something real – or he could be writing something fantastical, void of reality, something that’s never been. It’s up to him to tell us, but again, we can never be certain. We have to take his word for it, and as such, it has a compromised ability to constitute what we refer to as “evidence.”

A photograph, however, by its very nature, requires something to have been there, something existing as a physical thing in time and space, something that existed. This is the essence of photography for Barthes, and it’s basically the point of the book. Photography gives us a direct representation of the real.

Cogitate on that for a while, and think about what implications it might have for ‘post-analog’ photography…

Coming Soon, Part Two: What Barthes means in the Digital Era (hint: Not many people talk about it, although it should be fairly obvious)

Views: 2000

““I met a man at a party. He said “I’m writing a novel” I said “Oh really? Neither am I.”

― Peter Cook”

Semana Santa, 2008.

My wife fell, ended up with a broken hip that Sunday morning and within ten days had a new hip as well as her last cancer operation. November 2008 she was no more.

Not a lot of photographs hit me hard, but some dates (of the calendar type) do. The penitent, if that is what he is, strikes me as pure evil.

Maybe as particularly and specifically personal as punctum can become.

Anyway, I thought only the Greeks had a word for it?

Rob

My preferred way to describe punctum is “that special little detail, that secret something that pushes a photograph past the mundane to the sublime, which only a super duper specially sensitive soul, to be specific, that only Roland Barthes, can perceive”.

His notion of “blind field” is a much stronger concept than the studium/punctum drivel that always gets dragged out. But then, almost nobody has actually read Barthes, because he is more or less unreadable.

I appreciate you taking the time to summarize!

“Blind Field” = stuff outside of photo that we think about when we look at a photo…I think.

I quite like the concept of Studium and Punctum; strikes me as a useful way of applying critique and unmasking empty photographs with something that has a little more surface gravitas than, say, just a personal opinion. That by its application it will ultimately be exactly the same thing, doesn’t matter at all; it simply gives a convenient set of tools that can be applied to the messy subject of good or bad photographs. Not sure why I am writing this, as I do not like critique at all, because it’s little more than second-guessing, a field with too many experts.

I’m rather glad to have been introduced to those two entities; I was going to call them abstract entities, but are they really abstract? Studium can’t be, but then where there is no identifiable Punctum (can we now use lower case, do we know each other well enough to be that familiar?) it might be acceptable to think of it in terms of something tangible that’s missing, and therefore not actually abstract, but absent.

I gave up trying to do landscape photography, not just because it hardly thrilled me (but you have to do what’s available to you), but because all my shots seemed to me to resemble stages awaiting the talent’s arrival out of the changing room. No punctum, I guess. Wish I’d had that handy word much earlier on in this stage of my photography; it would have been terribly useful to have been able to throw it around online. 🙂

Little about Don McCullin is abstract; looking forward to seeing the BBC 4 programme about him tonight, Monday, 4th February.

Rob

There must be more than one type of punctum though.

Nobody except you Rob, could look at that picture of Semana Santa and have the same thoughts and feelings course through mind and heart… But suppose that “penitent” was jumping over a puddle?

Me thinks that too much capital is spent on deciphering what the snapper meant when he stood in that particular place at that particular time. Fun trying though, I suppose.

As for McCullin, I saw his show, and as I suspected, a BBC luvvie, even if he is a talented snapper. He is soooo left, it hurts.

As you say though, very little abstraction, except perhaps, his lack of self awareness… you would think that after 83 years, he might have got over the fact that everyone is different, and the poor don’t need his help. The best he can do is record what he sees.

Nice to see that the darkroom is something special, and not at all like the lightroom which is not shown, even though he clearly uses both.

I wonder if the Don McCullin show will be available in the US

Just been to see his exhibition at Tate Britain.

Technically brilliant, both making and printing, but…

… oh boy is he gratuitous or what?

Although the main topic of your post is not about black&white versus color photography I couldn’t resist quoting Ernst Haas as a counterpoint to the quote from Barthes you start this post with.

Ernst Haas wrote: “Color does not mean black and white plus color. Nor is black and white just a picture without color. Each needs a different awareness in seeing and, because of this, a different discipline. The decisive moments in black and white and color are not identical.

There are three different factors which have to be realized and balanced: form, content, and color. The last does not always benefit the composition. It can even go against it, in which case it has to be overcome. To translate a world of color into black and white is much easier than to overcome the color, which so often runs contrary to its subject matter. There are black and white snobs, as well as color snobs. Because of their inability to use both well, they act on the defensive and create camps. We should never judge a photographer by what film he uses – only by how he uses it.”

I have told my photography friends that a photograph is a photograph. There comes a time in Photoshop it is no longer one.

You may be onto something….

I like your blog. Some thoughts: The punctum is always subjective and it tends to erase the image. Barthes was much more subtle than indicated here. The reason Camera Lucida is such a famous book has more to do with the dearth of good writing on photography. That itself is interesting. Photography is quicksilver: once we think we’ve got it in hand, it slips away.

That is photography is a paradox. When it is “real” it is surreal. Similarly, basing a philosophy on photography’s lack of reality is also mistaken. It’s “unreality” is exactly what is real about the world that created it. Also, just as technology can be used to distort the truth of photography, encrypted unique ids can be used (created?) to ensure that what you see is what the camera recorded. It goes both ways. Focusing on this technological aspect is missing the forest for the trees as it is categorically unrelated to the main issue.

For example, Barthes’ title Camera Lucida is dialectical in that it subtly references the camera obscura – the gadget which, at the time, was used as the mainstream metaphor for photography. The camera lucida didn’t actually record an image. It’s representationalism was not it’s main reason for being. It was a tool that allowed the artist to be more precise. This is why the punctum is subjective in Barthes and is his main analytic tool over the studium, which is more closely related to photography’s “realism.”

Yes, something needs to be there for a photographic image to exist. This will always be true for a photograph regardless of how manipulated it is. But what is left from that encounter is the trace – and it is this quality that leads to much of the melancholy Barthes finds in particular photographs – the most emotional of which (of his mother) is never discussed or reprinted. I.e. he avoids using a photograph as objective proof. It pricks rather than overwhelms.

There is a color polaroid that Barthes includes at the front of the book – another witticism. Barthes hates color but includes the worst kind of color photograph, a polaroid, at the beginning of his book – and the most finely reproduced. This is because the polaroid is less detailed, less over-determined. A color photograph is more likely to fool you that it is the “real thing” something that “goes without saying.” Much has happened in color photography since then but that basic conflict between color and b&w still exists. Just look at the selfie, which is always in color. Once it is b&w, it is a portrait.

Interesting comments. My first reaction to your thoughts is that you’ve read too much Semiotics lit. Of course, I’m willing to entertain the idea that I’m simply massively generalizing what is a much more subtle argument. I’ll be the first to admit my intellectual deficits. That being said, part of my problem with Barthes and the entire Post-Modernist “discourse” is the opaque nature of the writing itself. Whenever I encounter ideas cloaked in specialist jargon my bullshit meter activates. I’m firmly of the opinion that clear thinking can be articulated clearly, and if your thinking is articulated with jargon, you’re not thinking clearly. Frankly, I think Barthes and the rest of 20th Century’s Post-Modernists – Foucault, Derrida, Delueze, Athusser, Kristeva, Sollers, Cixous, Guattari, Iragaray,Lyotard, et al- are engaged in a massive intellectual circle-jerk that intellectual historians will look back on and wonder WTF?

So, In short, may I suggest, as an alternative to your view that I’m over-simplifying Barthes, that you’re over analyzing him?

Leicaphilia. Sure, I accept those terms. I don’t mind being charged with over-analyzing just so long as I avoid being boring.

I think “photographs” or electronic images can now be created of “things” that do not exist, but that may really be no different from paper and pencil drawings or paintings of imaginary “things”. Does that make any sense?