Ludwig Wittgenstein. He Resigned His Chair in Philosophy at Cambridge University to Become a Shepard.

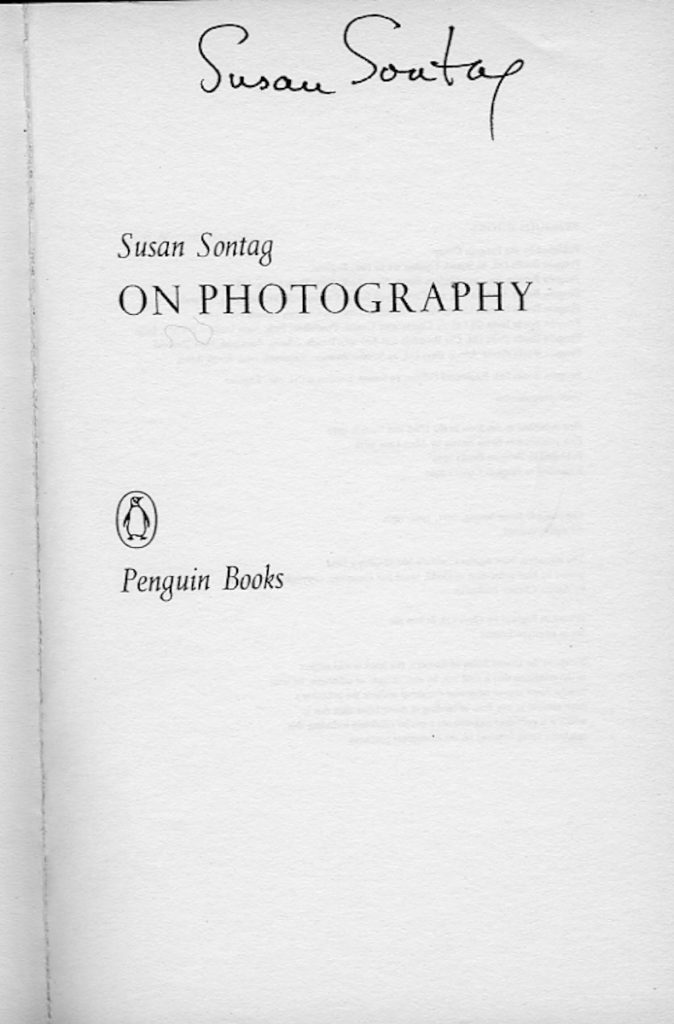

The last few posts we’ve been discussing the “ontology” of photography – what, at base, photography is. For the thinkers I’ve already written of – Jean-Paul Sartre, Susan Sontag, Roland Barthes, Jean Baudrillard – the important thing about photography, its claim on our imagination, is its relationship to what’s “real.” For Roland Barthes, whom we’ve discussed at length, photography was a memento mori, indexical evidence of what had been, and this is what gives it its uniqueness as a medium of representation. Similarly, for Sontag, photography was a “stenciling off of the real,” conclusive evidence proving the reality of the photo’s subject. Both Sontag and Barthes wrote prior to the digital age,  Barthes meeting his maker via a truck in Paris in 1980 (there’s an interesting recent French novel The Seventh Function of Language, by Laurent Binet, whose premise is that Barthes was murdered by other Semioticians), while Sontag did live into the digital age but never updated her thinking about photography (I met her in Paris in 2004, where she signed my copy of On Photography…which, you gotta admit, is pretty cool).

Barthes meeting his maker via a truck in Paris in 1980 (there’s an interesting recent French novel The Seventh Function of Language, by Laurent Binet, whose premise is that Barthes was murdered by other Semioticians), while Sontag did live into the digital age but never updated her thinking about photography (I met her in Paris in 2004, where she signed my copy of On Photography…which, you gotta admit, is pretty cool).

Sartre, Sontag, Barthes all saw photography as basically honest, allowing us access to the real, a function of its “indexicality.” They weren’t questioning the truth of photography itself. Baudrillard might be, but his issue was with the severing of indexicality, which is about a type of photography and not photography itself.

Now, I’d like to discuss an Austrian born “analytic” philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, whose criticism of photography is of a different type. Wittgenstein’s critique goes to photography’s roots, where even traditional indexical photography – the analog process where light stencils itself onto film – isn’t truthful. This is ironic because, for Wittgenstein, photography is a practical expression of his preferred means of perception, his motto being “Don’t think, look!”

*************

Wittgenstein (1889-1951) worked primarily in logic, the philosophy of mathematics, the philosophy of mind, and the philosophy of language. From 1929 to 1947, he taught Philosophy of Language at Cambridge. While alive he published one book, the 75-page Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921), one article and one book review. A second work, Philosophical Investigations, contradicting everything he had espoused in the Tractatus, was published posthumously in 1953. Bertrand Russell, Wittgenstein’s mentor – and subsequent protege – himself a philosopher of enduring significance, described him as “the most perfect example I have ever known of genius, ” and Wittgenstein is now considered a seminal figure in Western Philosophy. A survey of American university professors ranked the Investigations the most important philosophical work of the 20th-century.

Once you get past the work’s complexity, Wittgenstein’s main point is simple – not everything we know can be put into words. While most things can be said some things must be shown. In this, he agreed with Thoreau, who said that ” you can’t say more than you can see,” except that Wittgenstein goes further than Thoreau and believes you can see much more than you can say. More can be shown than can be said, because, for Wittgenstein, to think was not to mentally verbalize but rather to picture.

“Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent,” is the famous last sentence of the Tractatus. Unspoken is Wittgenstein’s premise the things about which we must be silent are actually the most important ( do you see what he did there?). We can’t verbally reason our way to these truths, as Western thought has tried to do since Socrates, but rather we need to look.

Given that, it shouldn’t surprise you that Wittgenstein was a photography buff. Apparently, he loved photography, annoying his friends by constantly taking pictures of them with cheap cameras. But, in spite of his interest, photography represented its own conundrum for Wittgenstein. It was not the problem of indexicality as it had been for Barthes et al. For him the problem was more fundamental, involving larger issues of visual representation and its capacity to reflect “the truth” of a thing.

Wittgenstein was doing something different than Baudrillard or the others I’ve previously discussed. For Wittgenstein, it wasn’t that photography lied as a process, it was that what photography produced didn’t tell the whole truth. Wittgenstein said of photography that it could only memorialize “what one glimpses.” A photograph was not a memorial, as Barthes and Sontag saw it, but rather at best a “probability.” The world of the photo could never be sufficiently complete in an existential sense; the glimpse it offered was too impoverished to present the truth.

Wittgenstein’s archive at the University of Cambridge includes the photograph below, a true “probability”. The woman in the photograph is a composite, created by Wittgenstein, overlaying four different photos of four different faces: his three sisters and himself.

In compositing the images, Wittgenstein was attempting to manipulate the photograph to transcend the partial nature of photographic truth, what he characterized as the difference between the “glimpse” and the long, studied look. To illustrate the difference, Wittgenstein notes what its like to watch someone without their knowing it: “Nothing could be more remarkable than seeing someone who thinks himself unobserved engaged in some quite simple everyday activity. Let’s imagine a theater, the curtain goes up and we see someone alone in his room walking up and down, lighting a cigarette, seating himself, etc. so that suddenly we are observing a human being from outside in a way that ordinarily we can never observe ourselves; as if we were watching a chapter from a biography with our own eyes—surely this would be at once uncanny and wonderful. More wonderful than anything that a playwright could cause to be acted or spoken on the stage. We should be seeing life itself.”

*************

Wittgenstein Would Say This Photo World is a Fiction

Greek philosopher Zeno of Elea (c. 490–430 BC) is best known for what’s called ‘Zeno’s Paradoxes,’ a set of philosophical problems formulated to prove that there is no such thing as change and that motion is an illusion. (If you think about it, that’s the same thing people who claim photography is truthful are saying, isn’t it?)

One of his paradoxes is of ‘Achilles and the Tortoise’. Achilles is in a footrace with a turtle. If Achilles, who runs faster than the turtle, gives the turtle a head start (100 meters, let’s say), Zeno claims that Achilles can never catch the turtle, ever. Why? Once the race starts, Achilles will run 100 meters, bringing him to the turtle’s starting point. However, during time Achilles is running the 100 meters, the turtle will run a further distance, say, 10 meters. Achilles will then have to run that distance, by which time the turtle will have run some distance again, etc. In theory, this should go on forever – whenever Achilles arrives somewhere the turtle has been the turtle is no longer there, and now Achilles has a further distance to go before he can reach the turtle, ad infinitum. Achilles can never reach the turtle.

Common sense tells us Zeno is wrong, even though, conceptually, he’s right. Wittgenstein would say that the belief in photography as true is grounded in the same conceptual mistake giving rise to Zeno’s Paradox: the claim that reducing reality to a static slice of time – a motionless state – can tell us anything about truth. Zeno’s philosophy presumed that motion, however actual to the senses, is logically, metaphysically, unreal. So too is the idea that photography could reveal to us a truth, the truth.

Wittgenstein says that photography can’t give more than a probability of truth. Contrast the quick glimpse of someone when they know you’re watching to the close observation of them when they’re unaware of you. That’s the difference between the photo and the truth. A photograph is a frozen moment, outside time, and thus a fiction. For Wittgenstein, photography can at best give a “snapshot…one of those insipid photographs of a piece of scenery which is interesting to the person who took it because he was there himself, experiencing something, but which a third party looks at with justifiable coldness.” To get at what’s true, your eyes must be open to the dynamism of reality as it flows via time. Don’t confuse the impoverished glimpse photography gives you with real seeing.

I think you could make a cogent argument that the difference between a “good” photo and a “bad” photo (for some sensible meaning of those words) is that the good one is *is* or at least *creates the impression of* being truthful, and a bad one does not.

Consider a “good” portrait. The whole point of a good portrait, really, is that in looking at it one gets the idea that one knows something of the sitter, that something is revealed beyond the surface impression.

The mechanism of that revelation is not something I have any grasp of, but I do think that it exists.

My theory is that the revelation is itself an illusion, which may occasionally, by accident, coincide with reality. You and everyone else may sense that the sitter was a warm and generous woman, and a good mother. And, maybe she was!

Love it. enough for me to think about for a long while.

I’ve just taken a photograph of Gare Centrale Brussels with a Summaron 35mm f3.5 manufactured in 1951, the year of LW’s death…!

That LW viewed a photograph as a probability is with hindsight (and given the work of Bohr, Schroedinger, Heisenberg and the tragic Hugh Everett) a natural development of the quantum wave function. In other words, given that every object we see is a wave function with a probability, then a picture of said object must also be a probability, I guess, right? Consequently truth (the human interpretation of what has really happened) must itself be a probability.

Quantum physics I understand still has not resolved which of (a) the collapse of the wave function or (b) the many worlds theory, is the mechanism that converts the probability into a certainty once the object is observed. So I guess, just like with quantum wave function, at a certain point of taking a picture, a photograph (whose indexicality is not broken) represents a collapsed wave function and is indeed now certainty. And certainty, I guess must be truth, though as we all know human interpretation can distort that truth.

In 1998 Perlmutter and Schmidt (I take a small sip of Oban 14 year old) provided evidence that the visible universe is expanding and the expansion is accelerating. Ultimately this leads to “heat death” (which the utterly brilliant Ludwig Boltzmann inadvertently predicted with an equation on entropy far more beautiful than E=mc2, namely S=kLogW). Now, if one had a Leica big enough with a lens wide enough and a negative sensitive enough to photograph the entire visible universe, that photograph (zoomed in enough) would show the position of every proton in the universe at that instant, whether that proton was in a star, a planet, a human, a lobster or a bacteria. There is no way anyone could argue that the photograph did not represent certainty, or the truth, as long as the indexicality was not broken.

LW is correct that the photograph is a poor substitute for standing back above the universe and gazing down and watching a lobster scuttle around. BUT WHAT ELSE HAVE WE GOT? I mean for all that rich stuff that LW saw with his own weird eyes, it is now lost to us, as Rutger Hauer said in the wonder that is Bladerunner: “all those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain”. Unless of course he left a photograph of what he saw, as impoverished as that photograph may be.

McCullin, Salgado, theirs is an impoverished vision? The Vietnamese girl running as napalm burns off her skin is a wave function with a probability that has collapsed to 100% certainty.

Ultimately with heat death the protons/electrons that make up analogue and digital photos will decay and all ability to represent what the universe and we once were will be gone forever. As Hemingway once wrote “our nada which art in nada, nada be thy name…”

Thanks for bringing this to us Mr Leicaphilia, as usual you provoke the cerebral cortex!

Now this Summaron really is a perfect object, who can do it justice? 🙂

JR

Don’t start me on quantum mechanics. That’s some seriously funky stuff – the effect of the observer on the observed, Schroeder’s Cat, etc. It obviously has implications for photography, but do we really want to go there in a Leica blog?

You can eat a roast beef sandwich with lettuce, tomato, cheese (I prefer cheddar) and a smear of Hellmanns mayo (up here in CT) or, from what I understand Duke’s down in your neck of the woods. Now, I’ve found that mayo on a RB sandwich just leaves a bad taste in my mouth. I much prefer oil & vinegar rather than mayo. Maybe it’s my nod to my northern Italian heritage. The sandwich has a cleaner, less oily aftertaste.

The last few articles posted here have been the mayo on the sandwich of photography [IMHO]. I prefer Elliott Erwitt’s approach to his photography, which is to basically avoid such ruminations on the who, what and why of his photos. Erwitt is my oil & vinegar.

Since our world is, at the moment, more messed up than ‘normal,’ why complicate things by screwing with one thing that seems to give us pleasure?

We can argue about bread choices if you wish.

I concur Dave, I am a bit lost with this stuff… Hold that vinegar though, it doesn’t go well with the Crohn’s.

Tim, keep up the good work though, life is a minestrone, as some poxy pop singers from Birmingham (Worcestershire) once sang.

You guys should have told me this when I asked i.e. my previous post. I asked, everyone said “more”….. so I gave you more. Now you’re complaining. I expect as much from Stephen, since he’s been yelling at me since I insinuated that country folks who voted for Trump and speak in tongues on Sundays might not be very bright. Dan, living in CT, I assume isn’t one of those people and is just being grumpy.

You guys should submit something. Dan, something a little less oily, less aftertaste. Stephen, I’ve asked you already, but you’re all too happy to have me serve up the chow while you eat for free, even though I suspect you’re sitting on a few bottles of first-growth down in the cellar. So don’t complain when you get served the occasional desiccated liver sandwich with low-fat Mayo and Velvetta cheese on white bread.

In any event, my next scheduled post, to be published Sunday, will wrap this whole Philosophy subject up with my take on it all, and then we can go back to fine dining, otherwise known as flogging Leica for their silliness and rolling our eyes at von Overgaard’s latest stupidity.

Photography once held the prospect of being a lucrative career.

Today, it holds the grim prospect of bending your mind. We need no gurus to attain that nirvana. I wonder how good any of those scribblers were at actually making photographs? Beyond her writings, can’t seem to find anything that intimately relates Sontag with photography other than Leibovitz. All those theoretical experts… I wonder how many of them stood there, camera in hand, observing their model and knowing what to do next in order to catch what they have not yet seen?

I think there might be mileage in writing about the state of mind of the surgeon doing a heart transplant. Oh, wait; didn’t Dr House cover all those fields?

😉

You make a valid point. Sontag was married to Leibovitz, so I assume she had some first hand knowledge of things. The others, probably little if any. One thing you do realize if you’ve studied philosophy in an academic setting is that the sort of minds that gravitate to philosophy usually aren’t very creative.

Well, you have personally provided the exception that makes the rule.

I don’t think folks have really been asking you to call off the philosophical dogs as much as suggesting those guys and gals may not hold the best cards at the table. I mean, Achilles and the tortoise… that’s so dumb that I wonder how it lasted as a quotable quote all these centuries. Must have been in the Reader’s Digest.

Poor old Zeno. Had he had the luck to be a Roman rather than a Greek, he’d have discovered relativity in the speeds of the various animals doing their number at the Coliseum.

I found your philosophers quite interesting in the contexts in which you embroiled them, if not entirely convincing on all counts, but hey, they would be facing different realities today, just like photographers. And if most of us are still a little confused…

Rob

My flickr site is flickr.com/photos/dcastelli9574/ Sign in and read my bio., look at the pics.

Go to Japan Camera Hunter and search for bag submission # 1290

Go to 35mmc & search under Technical Know How and find my in depth article on my darkroom.

I’ve also published a “Five Frames with a Leica CL” on 35mmc.

You all can do some work – I won’t provide links.

That’s not northern Italian, its positively deep south in its laziness! Almost mañana country.

🙂

My Italian grandmother hailed from a tiny town just northeast of Turin. We never had red sauce on any dish…she made a killer Bolognese sauce, but that was the extent of any tomato based sauce. Never was near the Med. My late uncle landed at Anzio, fought his way up the boot to Rome. That was the closest any of my relatives were to the Med.

Lazy? Emigrated to the US when she was 12. Alone. Bought a broken down farm, and turned it into a successful operation. Raised pigs, chickens, cows. Shared what she had with the hungry from the depression. Widow w/4 children (my dad was the oldest.) Lived to her late 90’s. Had a garden up to the day she died. Professional chefs would kill today to have the garden she had. Taught me to make pasta. Was all of four feet, 10 inches tall in her orthopedic shoes.

She was our connection to the ‘old country.’ The day she became an American citizen, she never spoke her regional dialect ever again. “I am an American, I will speak only American.” Of course, she was almost impossible to understand in her fractured American, but you always got her point. Nobody messed with Grandma Chelesta.

But, sorry, her dressing of choice was always oil & vinegar.

And mine from near Trieste. For decades I thought that I spoke clumsy Italian, only to be told no, that’s rather old Veneto that you spout.

In present reality, northern Italy despises the Mezzogiorno (aka the south), and that’s reflected in today’s political parties. Exactly as with Spain, where the north (Cataluña) feels, with some justification, that it subsidises the rest of the country down south.

Exactly the opposite of Britain, where the very wealthy south pretty much supports the remnants of ego of the once mighty and proud engineering north, now largely mired in the remains of obsolete industrial heritage.

I guess we will one day see our own emergent Trump playing that cynical, regional card of rejuvenation.

Rob

Critical, condescending and crass, in three short paras.

And so it goes.

Think of it as worth what you pay for it.

Careful with that

axehandbag Eugene.I’ve particularly enjoyed this detour. My student years were full of Barthes, Wittgenstein and Sontag. I still have a copy of the Tractatus and for some reason, two of On Photography in my bookcase. Damned grateful for someone else doing the heavy lifting now.

As have I, Tom.

If there’s a problem for me, it’s in my genesis in the pro world, where all of this comes over as attempts to subvert photography to personal aggrandisement and the gentle rustling of old alma maters. My own alma mater was, literally, my mother, whose collection of books on art did everything to nurture my interest in things that go down on paper. My aunt, on the other hand, was my introduction to Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar magazines. Those two ladies had more influence on my life than had any male in my early environment.

Part of me is too cynical (perhaps) and I tend to suspect some writers of being less than truthful and very much writing for effect. And, of course, for their peers. On the other hand, there is ever the thought at the back of my mind that I really should try to catch up with so much stuff… that is always flattened at birth by the other voices that tell me it matters not, and that it’s more worth the while just doing my own thing – if anything at all.

There is also the thought, valid or otherwise, that carrying too much information about photography in one’s mind may actually be counterproductive. My experience has been that I function best as a photographer under two conditions: lack of time; no precise client instructions. I’m reliably informed that the second factor is, today, largely unknown. Glad that I did what I did when I did it! How I’d get on carrying further burdens of philosophical approach as I wander around snapping the occasional snap today is anyone’s guess!

Rob

http://www.roma57.com

Rob: You don’t need to carry this stuff around. In fact, you’d be best not to. But I do think that having a “philosophical” understanding of the process in your head, tucked away somewhere below the level of full consciousness – a meta-narrative of what you’re doing – will make you a better photographer, make you more apt to see subtle things that might implicate these issues, might then animate your photography…and might be picked up by an astute viewer.

I’m glad you have, Tom. If I remember correctly, you’re the University philosophy professor – head of your department – at a very respectable University here in the States. For you to like what I’ve done is very gratifying. I suspect you’re too kind to point out where I err.

I do think that photography and its relationship to truth is a great way to frame discussions of 20th century PM thinkers, certainly for undergraduates who might need a handle with which to manipulate what are very complex ideas. Why not an undergrad course “Are Your Selfies Real?” or something like that.

I think philosophy, when taught correctly, can be transformative. It certainly was for me. A HS dropout, my first foray into academia was at a modest directional college (the ones that start with “North” or “west” etc), where I studied Philosophy. I loved it, because it was taught in a way that wasn’t solely academic. We read a lot of accessible works like Plato’s Euthyphro, Crito, Phaedo, Apology et al and little of the academically fashionable work like Habermas, Derrida, etc that I’m convinced no one will ever give a second thought to in a few years. I then went on to graduate school at Chapel Hill, where their Philosophy department is considered one of the best in the world, and found what they did there basically incomprehensible.