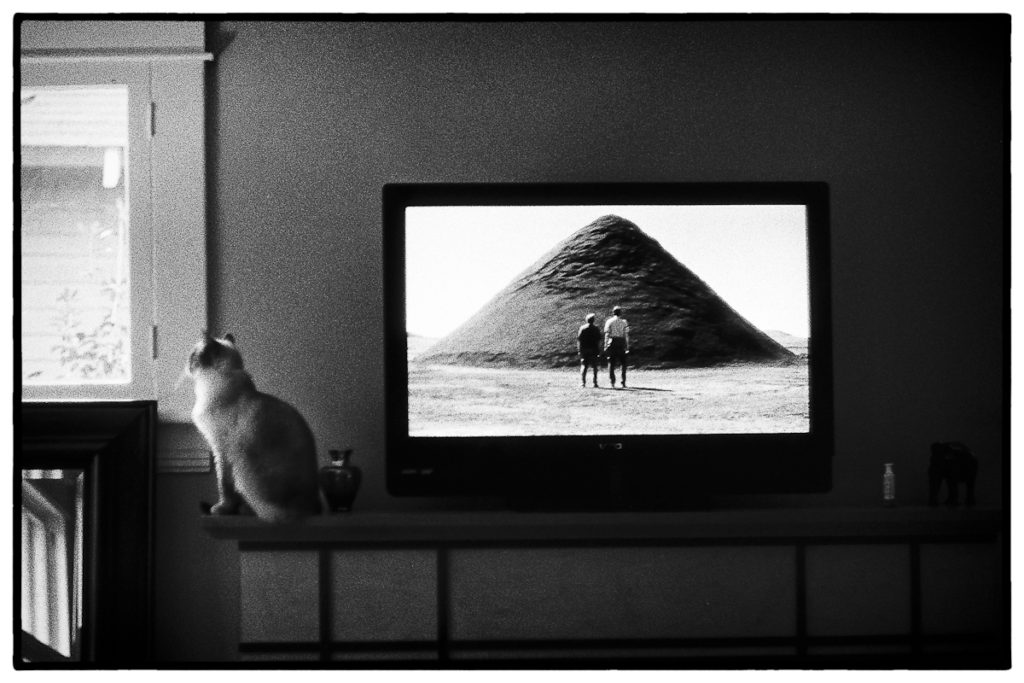

This isn’t “just” a Photo of my cat Sitting next to my TV. Freud would say its an X-Ray of My Psyche

One of the more interesting places I’ve visited is the psychoanalytic office of Sigmund Freud at 19 Berggasse in Vienna, interesting for me, at least, because it was one of the few places in Vienna I found interesting (nothing against Vienna; just personal preference. Vienna is just a little too clean and orderly for my tastes. I much prefer more down at the heels – e.g. Marseilles, Naples, Detroit). What immediately struck me were the photos that hung on the walls. Freud clearly had a thing for photography. A connoisseur of art, Freud adorned his walls with both photos and paintings and covered his shelves with various cultural knick-knacks. It’s important to remember that Freud’s psychoanalytic theories took shape and matured during the early years of photography, and, as I suspected while visiting his office, photography formed more than a casual influence on his thought.

Jean-Martin Charcot, an important mentor of Freud, used photography to record and study seizures and hysterical expressions and postures. Likewise, G.-B. Duchenne, neurologist and electrophysiologist who worked with Charcot, sought to understand neuropsychiatric patients via photographs of their faces and body postures. Freud owned the 1876 French edition of Duchenne’s Human Physiognomy, where Duchenne had published his studies. Duchenne’s photographs profoundly shaped Freud’s thinking; Freud repeatedly used the metaphor of photography—the photographic negative, in particular— as a means to illustrate his theory of the unconscious.

Mary Bergstein, Professor at the Rhode Island School of Design, suggests that “photography penetrated the cognitive style of Freud and his contemporaries,” and “documentary photography—of art and archaeology, but also of medicine, science, and ethnography—influenced the formation of Freudian psychoanalysis.” For Freud, the fragmentary and evocative nature of photography mirrored how human memory works; the mind’s eye, both conscious and subconscious, mimics the photographic lens.

************

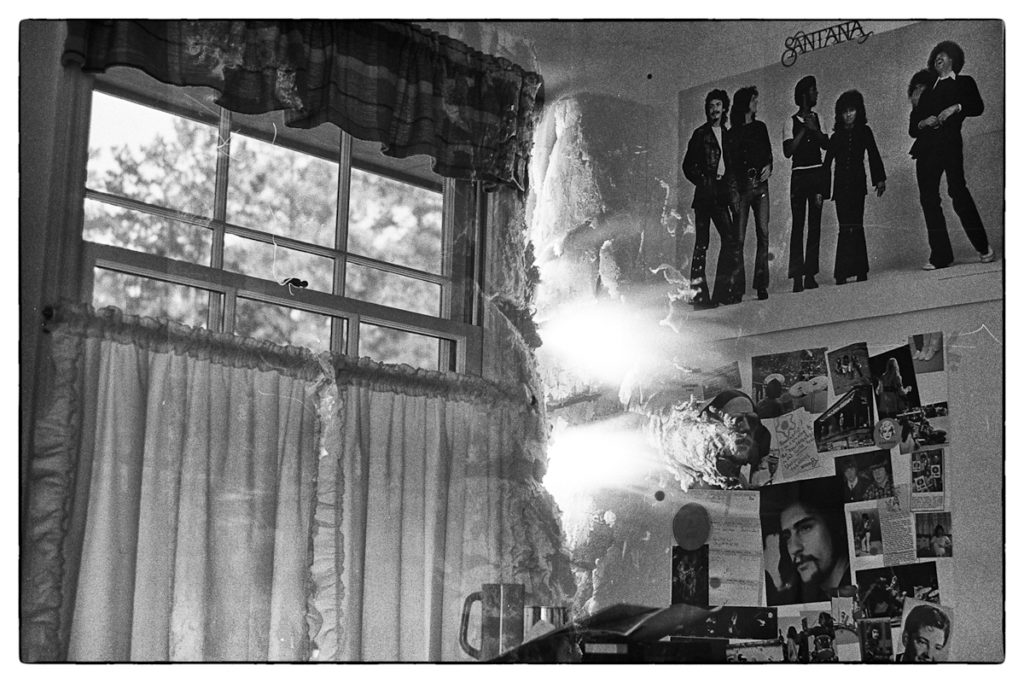

A Deliberate Double Exposure: My 12 y/o Attempt at Profundity, circa 1970. God only Knows what Freud Would Make of It

A more interesting issue, apart from Freud’s use of photography as metaphor, is his understanding of the ontology of the photograph i.e. what is a photograph? In Freud’s era, photographs were viewed as transparent windows revealing objective truth but at the same time were thought to be subjective and dreamlike. A photo of a ruined temple, while depicting a specific place, also conjured loss, oblivion, the highly emotional reminders of the passage of time. This produced a lot of really bad, pretentious photography (google “Alfred Stieglitz” for further details).

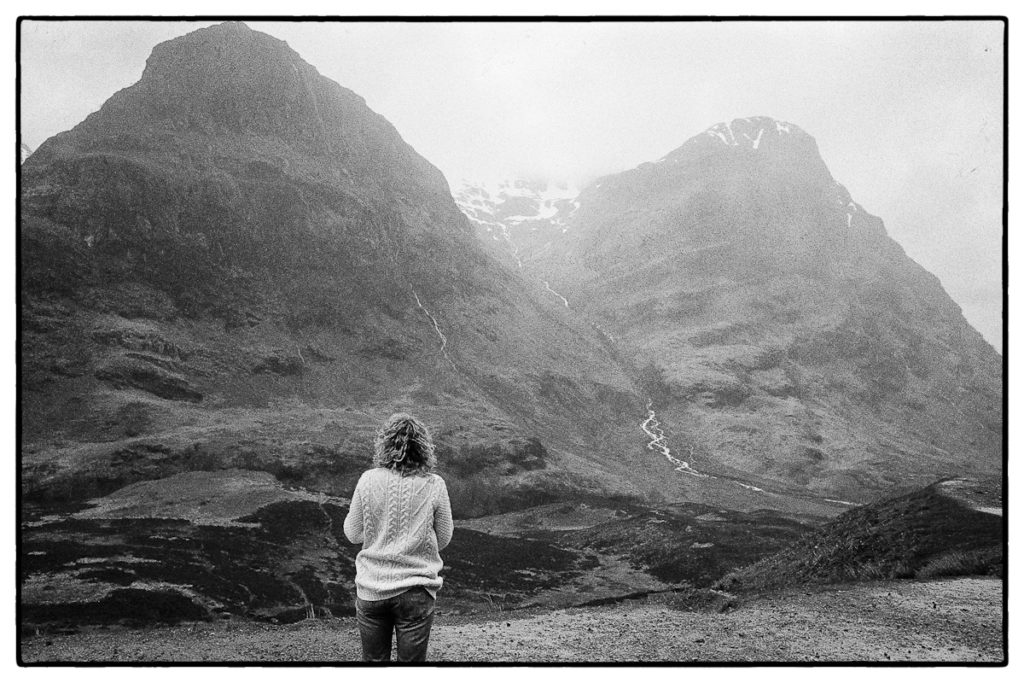

For Freud, far from simply producing a transparent image of reality, photographs manifested what cultural theorist Walter Benjamin called the “optical unconscious,” a term Benjamin coined to denote the visual depiction of unseen, the terrain of the imaginary. Benjamin’s concept raises the issue of the photographer’s unconscious communication. The ruined temple photo, for example, while conjuring loss, oblivion, time passing or whatever for the viewer, Freud saw also as giving entry into the coded language of the photographer’s psyche. Photography captures scenes that pass too quickly, too remotely, or too obscurely for the subject to consciously perceive. However, Freud would say that our unconscious – which is the real seat where our personal truth is found – takes in everything. The camera pictures phenomena that the photographer has unconsciously registered but not consciously processed.

Think of your unconscious as the curator of your photography. There are no accidents in photography. According to Freud, everything we present in our photos has been screened and found compelling by our unconscious psyche. Every one of your photos is your optical unconscious made visible, demonstrating the reach and complexity of your unconscious perception and, properly analyzed, gives access to the hidden psychological realities that animate you, including the style and structure of your perception, and the more nebulous regions of your psyche.

Don’t know much about psychology – other than of my own – but yeah, chickens/egggs: what you produce is all about what and who you are, which is why I always espoused the belief that photographic content can’t be taught because it’s about the self.

To me, that’s so bleedin’ obvious that I really wonder how it is that folks get roped into doing courses and all that stuff when all you need – or can? – be taught is camera and darkroom or computer use.

I can imagine myself trying to imitate the landscapes of Kenna, the street art of Leiter, but the thing is, I’m neither of those two and all I could produce would be my own takes on their subjects, not a reproduction of their style. It’s never that easy.

I know that specific photographers strike chords in our hearts, probably because of sympathy with their aesthetic and possibly an admiration for their uniqueness. Of course, that’s not to preclude admiration or, rather, appreciation of some people who have great technical ability in a genre that isn’t particularly one’s own, but there’s a big difference between the way the groups are appreciated. For instance, when I run out of online forums to which I feel inclined to add some input – that there are only three makes it easy – I inevitably switch the iPad to collections of either Sarah Moon or Deborah Turbeville images. I am so familiar with them by now, but still find them totally absorbing, despite the fact that my own model work was radically different if only because of client desires. So why do those photographers grab so tightly? Is there something about the female perspective that surpasses the male ability to dig into atmosphere? In the male world, it’s always Hans Feurer and the aforereferenced Saul Leiter who draw my attention; Leiter for his colour sense and Feurer for his long-lens ability to cut to the chase and make the subject really the subject, devoid of more than the most mere of suggestions about location.

I suppose that one should count oneself fortunate to be able to find pleasure in those photographers who hold up mirrors, not to ourselves, but to the subjects and images just that fraction out of step with our own. It’s beautiful to be able to see more than just one person’s wonderful reality.

A wonderful addendum. Thanks, Rob.

To tell you the truth, I find your site much as I did Hef’s Playboy Magazine during the 60s/early 70s: a sometimes incredibly teasing challenge to my word power, and in a far better environment that did the Reader’s Digest of the 50s. So many words I think I know, only to feel forced to check ’em out and discover I’m just partly there.

As Klein might have said: Life is good & good for you in Leicaphilia!

What happened to that other final image!? I was about to comment how I totally thought it an amusingly appropriate shot. You know, probably not shot when you were twelve, but with the mind of a twelve year old. In a positive, supportive , and respectful way, mind you: I pride myself for still feeling like a twelve year old, not in a freudian sense (neccesarilly), but as a source of wonderment and creativity.

I edited the piece down. I reread it and thought it too unfocused…and took out that photo. But I think you’re right, it needs to be in there.

It’s a bad habit of mine: I tend to just write something off the top of my head and post it without editing it, then go back in a day or two and read it and edit it. In this instance I cut out an entire middle section and then removed that photo, but, as you noted, the photo actually works quite well with the other two and with the written content, so I’ve put it back in.

The last image works there quite well indeed!

Freud was a bit bonkers, wasn’t he? I guess when you’re out there on the frontier, things will look a bit odd to you.

And then you have to add in the fact that spending time with others slightly spaced out – as we both know from other websites – adds to the sense that if something is possible, then it might actually have some moral validation by virtue of its possibility. It’s hard to retain your sense of lines of demarcation in all of these things… it’s all the noise.

Bonkers maybe, a good sense of business, certainly. Psychoanalysis is a cash cow and freudianism is a cult with its high priests: Or you buy or you don’t. Personally, I don’t.