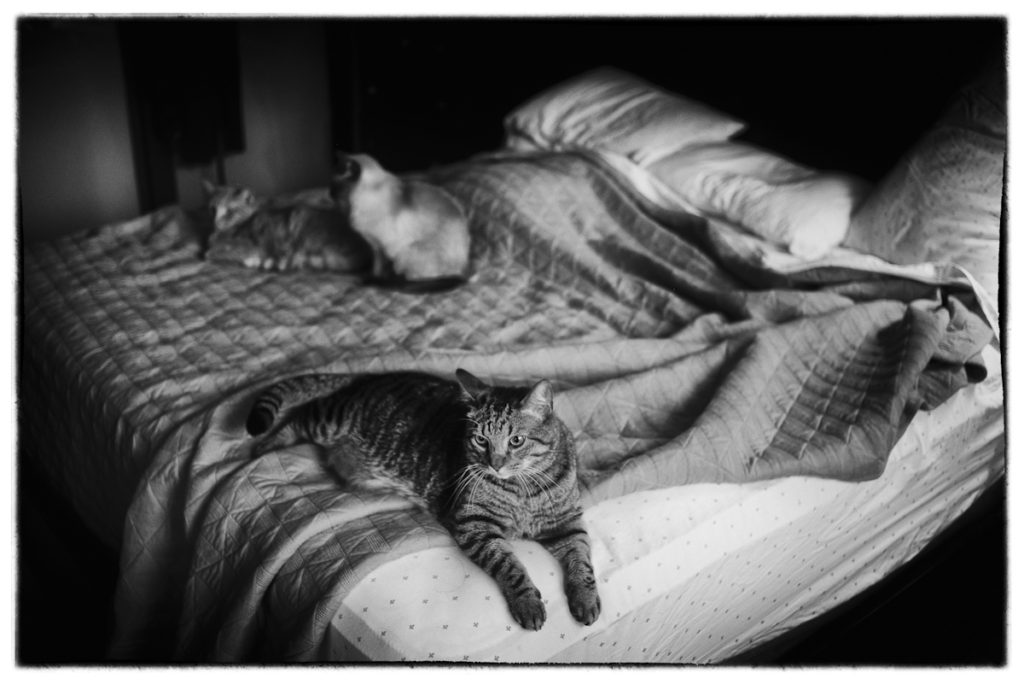

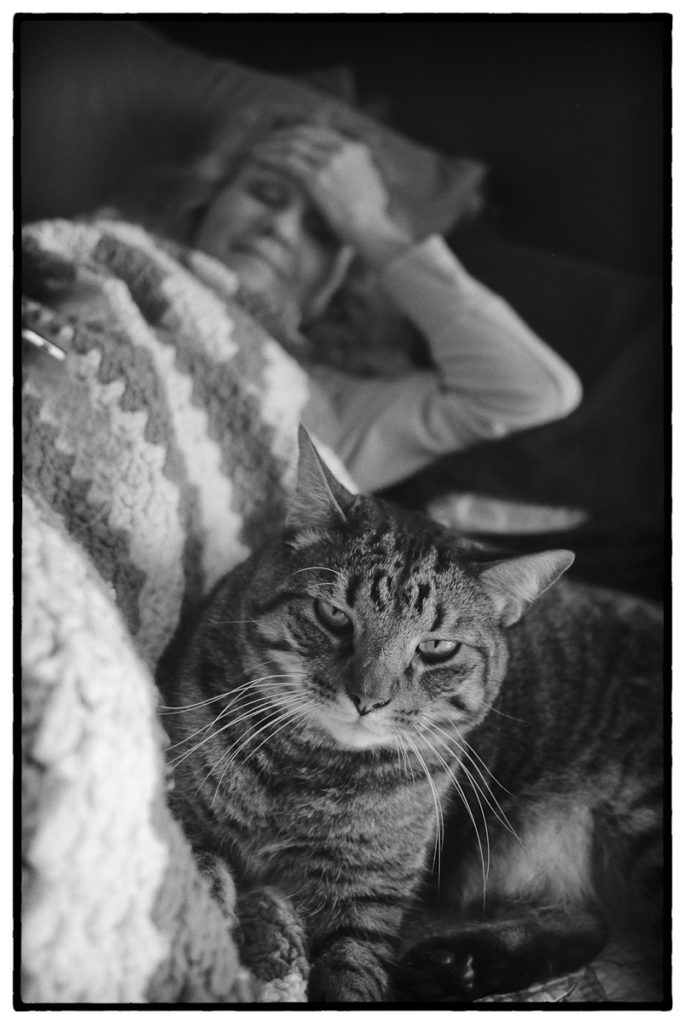

Every Leicaphile Loves a Good Cat Picture. This was Shot Digitally, But Looks to Me A Lot Like a Well-Printed Film Negative, Plus-X Maybe?

I make no secret of the fact that I love the look of 35mm B&W film. A properly exposed, competently printed 35mm Plus-X, Tri-X or HP5 negative has a beauty that simply cannot be matched by a digital file of whatever native quality. In comparison to the film print, the digital print will always have a certain thinness, a lack of heft, a “plastic” look. While it’s hard to put into words – given we’re talking of visual matters – it’s there, I can see it, it’s real (I think).

There’s an organic quality to a film print, as best I can tell the product of four inherent characteristics of shooting film: 1) silver grain as the light-transforming medium; 2) better highlight rendering, the result of the fact that film, unlike digital capture, does not record exposure values linearly, as does digital capture, but compresses those values at both ends of the exposure curve, giving better highlight definition (e.g. it is less prone to “clipping” highlights) and deeper, “richer” shadows (old-school film photographers know exactly what I’m saying here, digital era photographers will mostly be clueless – for further discussion, see this); 3) the inherent resolution limitations of general purpose b&w films like HP5 or Tri-X, which, to my eye, equal in look somewhere between 6 and 8 mpx of digital resolution, in combination with the less resolute optical characteristics of film era lenses, which were developed to give an appealing look within the confines of limited film resolution; and 4) the necessity of shooting at the low ISO’s required by film. Put all of four of these characteristics together holistically, and you have the “film look,” a result of both the native strengths, and inherent limitations, of silver halide as a medium.

Unfortunately, that “film look” is difficult to present online in the sense that a scanned film negative – a requirement to presenting it for web viewing – looks different from a wet printed film negative, the difference created by the digitization itself. Scanned film negatives usually have more pronounced, harsher grain that is not present in a wet printed version of the same negative, the result of the relative harshness of the scanner’s light source, which artificially accentuates grain when compared to the same sized wet print, where the enlarger’s light source is more diffuse and produces smoother grain texture. Anyone whose both wet printed and scanned and then inkjet printed the same negative knows precisely what I’m talking about, but it can’t be represented digitally because scanning is a necessary prerequisite to do so.

*************

The CMOS Version Leica MM

Given my preference for B&W, which to me is “real” photography, I admire the Leica Monochrom cameras, and I admire Leica sticking their necks out to produce them, an example of Leica at its best, attempting to carry on their patrimony into the digital age. However, unlike how they marketed the MM – bundled with Silver Efex and referring back to 50-60’s era B&W photography – the MM isn’t going to digitally replicate B&W film; at best, it’s going to create a new look – “digital B&W”. [ Ralph Gibson seems to understand this]. Given what was said above, it becomes obvious why a dedicated B&W digital camera can’t digitally duplicate traditional B&W photography. Stripping the color out of the capture won’t address the inherent exposure curve differences between analogue and digital capture, and the increased resolution of the Monchrom vis a vis standard 35mm B&W film compromises the look as well. Given the native differences in capture, no amount of running the Monochrom digital file through film emulation software will accurately mimic real B&W film.

Where the MM might have an advantage in replicating the film look might be to the extent it allows use of older film era rangefinder lenses. Mandler era Leitz optics give a certain signature we equate with film capture, both in the look of how they resolve details and also in the look given by lenses with the small film to flange distances typical of rangefinder as opposed to Reflex systems. Of course, this would only be true to the extent when we’re speaking of a traditional “film look” what we really mean is the look give by 35mm film rangefinder photography. If so, then the MM can’t in any way be inherently better than any other full color capture digital Leica rangefinder (e.g. M8,M9,M10) given the defining shared characteristic is a function of film to flange distance unique to any digital rangefinder or, for that matter a mirrorless design, that allows the use of traditional rangefinder optics created to take advantage of small film to flange distances. My experience with the lower resolution M8 confirms this: I’ve always thought a greyscaled M8 file with some grain added looked more like native B&W film than did the files from the MM, probably a result of the M8’s decreased resolution coupled with its ability to use film era Leitz lenses.

*************

The Fuji S5 Pro. Its Files Look A Lot Like Film. There’s a Reason…

Which gets me to the premise of the title of the post: much of what we identify as the strength of film – the film look – is a consequence of its limitations, its imperfections, imperfections that are a part of its character. As digital technologies have advanced and matured, the photos they produce, while closer approaching a technical “perfection,” have lost character. As a consequence, those of us educated by experience to notice it often end up dumbing digital RAW files down to mimic the imperfect look of film.

For my money, the Fuji S5 Pro digital camera, produced by Fuji in 2007 using the Nikon D200 chassis and Fuji produced Super CCD SR (Super Dynamic Range) sensor, comes as close to replicating the traditional B&W film look as any digital camera I’ve used. It may be just me, I don’t know, but the S5 files, run thru Silver Efex, even without using any specific film emulation (e.g. no specific film exposure curve applied, just grain added), have a certain solidity to them, a lack of that “plastic” brittleness often characteristic of digital black and white. After thinking about it, I’ve concluded that the S5 mimics the traditional B&W film look because of both its unique extended latitude sensor but also because of its inherent technical limitations.

The SR Sensor found in the Fuji S5 Pro – either 6 or 12 mpix depending on how you define it – offered almost two stops more dynamic range than conventional CCDs of the same era (2007, roughly the M8 or D200 era). Beneath each micro-lens on the sensor surface are two photo-diodes, the primary capturing a dark and normal light levels (more sensitive), the secondary capturing brighter details (less sensitive). The signals from the two photo-diodes are then combined by Fuji’s in-camera software to deliver an image with extended dynamic range. What’s of interest for film users is the way the extended dynamic range is achieved. Unlike normal cutting edge CMOS sensors that give excellent dynamic range, the Fuji gives a certain type of dynamic range, a type that more closely mimics the type of dynamic range given by film, the added latitude at the highlights. Like film, you’ve really got to work to clip the highlights on an S5 DNG file.

Fuji S5 RAW Run Through Silver Efex to add Grain. No Specific “Emulation” used i.e. Tonal Range is as S5 Sensor Captured It

A lot of this is subjective, no doubt. There may be something similar to a “placebo” effect, where believing is seeing. I’m willing to entertain the possibility that I’m as clueless as this guy when discussing my preference for the Fuji S5.*** What I do know is this: I really like my S5 for B&W capture, especially when I print as the end product. It checks many of the film experience boxes – low ISO capability (500 ISO is about as high as you want to go), having to work within the constraints of limited resolution, ability to use film era lenses (in this case, old MF Nikkors for the 50’s-70’s), excellent highlight rendering. Much like a 35mm film camera, the S5 is a camera that’s as much about its limitations as its strengths, limitations the photographer must work around, or within, the resulting images in part a consequence of those limitations.

The irony is that most people chase the film look by looking to digital cameras with ever increasing resolution, dynamic range, ISO capabilities etc, when a more thoughtful, and effective approach, might be to embrace technically less capable digital tech like the Fuji S5.

[*** “Comparisons” like this guy’s tell you nothing, typically accompanied as they are by statements like “However, there is an impression of clear intent demonstrated by that lens” (huh?) . This is the sort of fuzzy thinking cloaked as rational analysis that drives me nuts. Which begs the question: Am I doing the same thing? I suspect that some folks will see this essay as basically the same thing – a word salad dressed up objective analysis. And then there’s the cat pictures….]

Limits—self-imposed or otherwise—also tend to enforce creativity. I dig that.

Ingenuity maybe, in the sense of overcoming equipment problems, but creativity? I doubt that very much; more likely to induce frustration and a feeling of the hell with it!

I lived through a period where I had to use a Mamiya TLR with a 180mm lens to shoot my 6×6 headshots; frustration was the sole payback relieved only when I could afford a Hasselblad 500 Series camera system and put parallax forever out of my life.

Limits are positive only when you can’t avoid them, and so convince yourself otherwise via acts of huge self-deception. Nothing compares with freedom. If there is one avenue of self-imposed limitation that sometimes works – did for me – it’s time: push towards the end of a deadline and feel those juices flow!

Of course, as always in life, someone else’s MMD!

😉

Your comment has been knocking around in my sub-conscious for a day or two, Mark, probably because there’s something about the term “limits” in this context that doesn’t seem precisely right, but I’m having a hard time defining what my objection is. I think it’s this: “limits,” connotes something slightly defective, not whole, as if there’s something problematic in the experience that we need to work around. I don’t necessarily think that’s what you’re saying, just that the words we use can mis-characterize the experience. Maybe what I want you to say is that working within a certain technical or aesthetic paradigm can sharpen one’s creativity.

There isn’t any particular reason why digital cannot produce a thoroughly filmic look, as long as we’re inside the range of exposure the two mediums can handle (about which more in a moment). Mostly “film presets” don’t even come close, they’re just terrible imitations of what hipsters imagine film looks like.

From ToP: underexpose by 1/3 of a stop or so, and place a generous shoulder and toe into your tone curve to roll off highlights and shadows pleasingly. Then a large-radius unsharp mask lightly applied to taste seems to push the contrast around in a good way (I do not know the mechanism here, at all, but it seems to work.) Apply a little fake grain if you want.

Now, nobody *does* this, of course, so digital photos do tend to look different.

Also, and this is where things get interesting: film and digital fail completely differently. Digital audio is distinguishable from analog only by the fact that it is better, within the dynamic range of the equipment. Overdrive it, and things fall apart radically differently.

Staying within the dynamic range of photographic materials and equipment is rather trickier, though, since you can’t just dial back the gain on the sun, or the specular reflections.

“From ToP: underexpose by 1/3 of a stop or so, and place a generous shoulder and toe into your tone curve to roll off highlights and shadows pleasingly. Then a large-radius unsharp mask lightly applied to taste seems to push the contrast around in a good way (I do not know the mechanism here, at all, but it seems to work.) Apply a little fake grain if you want.”

Easier than this, just run them thru a film emulation software like Silver Efex which in effect does the same thing e.g. takes the linear capture of a sensor and places on top of it a mask that emulates the characteristic exposure curve of any given film while also giving that film’s grain structure. As for the underexposure, it’s a good general strategy for avoiding the clipped highlights characteristic of over-exposed digital capture.

But……to my eye, these strategies only go so far, and invariably they don’t quite get it. Maybe it has something to do with the fact that the exposure curve and the grain are added after the fact i.e. they’re not an intrinsic result of the capture itself, and also, in limited instances, a “generous shoulder” added after the fact isn’t going to solve the problem of clipped highlights when there’s no native information to work with i.e. they’re “clipped.”

Probably, I’m just overthinking it and it’s a placebo effect, who knows. I do love my S5 though, one of four digital cameras I’m partial to because of their B&W rendering: the M8, the Ricoh GXR with M Module, the Sigma SD Quattro…and the S5.

Well, yes, that’s why you underexpose! If you clip the highlights, then you’re into the land where digital and snacks fail quite differently and the game is usually over.

Sometimes you can cover it up adequately, sometimes not. It’s still my go to spot to examine when someone claims to be shooting film (surprisingly often they’re not).

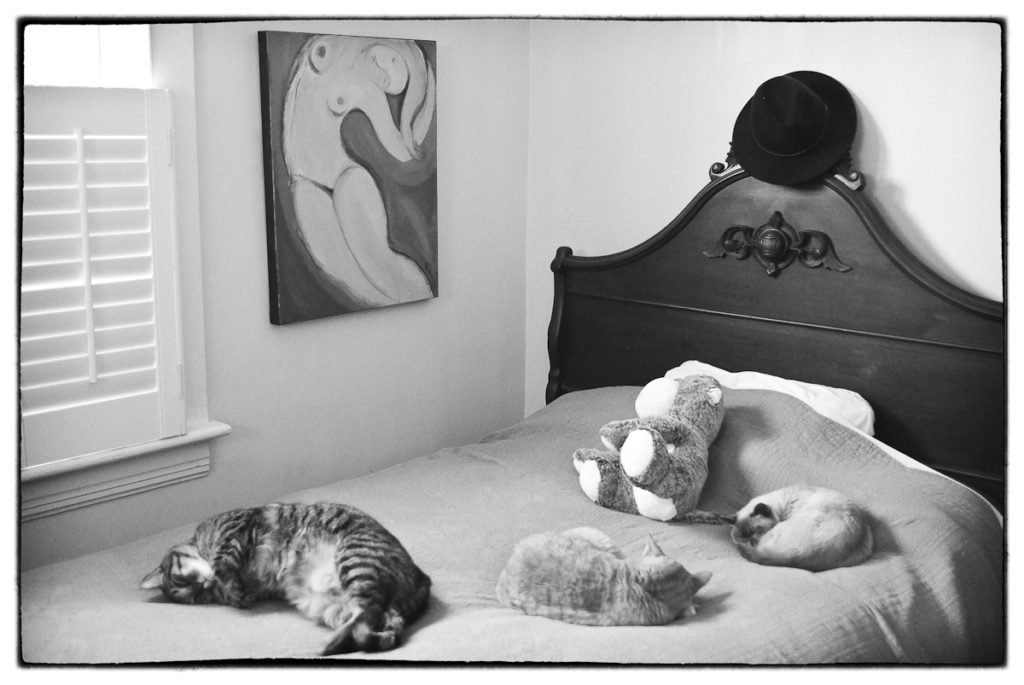

You can have the worst day of your life: lost your job, your spouse left you and your bank account was hacked by a 13 year old in some country you didn’t even know existed. You dog, however, doesn’t care. It will sit next to you wagging its tail and trying to climb into your lap. It will show you unconditional love.Your cat won’t come near you until you feed it. It will then cop an attitude of ‘is that all you’ll do for me?’ Snapping a pic of your cat with a digital Leica will not change it’s attitude. Your dog will see your historical double-winder, limited edition M3 with the modified viewfinder fitted with a low serial number Summilux in your hand and get all excited because it means squirrel chasing time. Life is good.

No question. Dogs are the Universe’s way of apologizing to us for the absurdity of existence. Cats are proof of the absurdity of existence.

I own the original CCD M Monochrom and also shoot a lot of Ilford XP5. Yes, they look different, but neither is better. I look at the MM1 as essentially three different film stocks.

At low ISO (320-800) it is like a T-grain film, but with a very flat tonal profile and extremely fine “grain”. Imagine a T-Max 25 with tones similar to Pan-F, but lower contrast (plenty is there to push and pull in post).

As mid ISO (1600-2500) it is much like a flatter toned T-Max 100, again very fine “grain” and a wealth of detail in shadows and unclipped highlights (always underexpose with an MM).

At high ISO (5000-10000) it is like Tri-X or HP5 (ISO 5000) or the same films pushed to 3200 (MM1 at ISO 10000). Crunchy tones, adequate detail and very grain-like noise.

I was an early adopter, getting my Monochrom in early 2013, and it remains my favorite ever digital camera and a very close second to my M5.

I could not agree more; after shooting film for several years i switched – mostly (I still have my M4 MP and and a couple more old ones) – to digital, and my main shooter is a (CCD) MM. Phenomenal camera, ridiculously good images….but in spite of being all in B&W and all processed through Silver Efex, you can always tell them apart from ‘real’ film.

I also used to get really good B&W from my M8, better so than the M9 i got subsequently.

I think the problem is that these digital files are simply ‘too good’ … one gets higher resolution, better ‘quality’, but loses something that is hard to pinpoint.

I do get excellent B&W images out of the MM, of course, and even my Ricoh GR and the Sony RX1R produce great results once converted and processed through Silver Efex – and, of course, the flexibility and ease of use of digital makes it all very compelling.

In the past, other than the M8, i found that the best digital cameras to get ‘film-like’ results were the Sigma DP1 (not the Merrill or the Quattro, those are again ‘too good’), and the Epson RD1 (which had the added bonus of a mechanical shutter which had to be cocked like on a real film camera!

You should try one of those small DP1 cameras, they are fairly inexpensive nowadays, the files are small and easy to process, the shooting process is close to analog (slow and thoughtful, no spray and pray possible, limited ISO capabilities); i think you might really like it!