French Post-Modernist Intellectual Roland Barthes, Pondering the Studium/Punctum Distinction With the Aid of Non-filtered Gauloises

Consider this Part Two of my previous post on Barthes’ Camera Lucida. There, I gave what I considered the gist of Barthes’ thesis on Camera Lucida, the main point you as a photographer can take away from the book. My intent was to de-mythologize the book and make it intelligible to an educated lay readership. In my opinion, any thinker who can’t articulate his thought so that it’s understandable to an educated lay reader probably doesn’t have very coherent ideas to begin with.

Which is not to say Barthes didn’t have much to say. He did. He just suffers from the annoying tendency of “French Intellectuals” to make their thought sound more profound than it really is by expressing it in jargon that obscures it. This has had the unfortunate result that it’s also allowed less interesting thinkers than Barthes, or often thinkers with nothing to say, to join the debate simply via having mastered the appropriate in-group jargon (read this woman if you have questions). Much of modern Semiotics thought, of which Barthes is a pioneer, is, honestly, a mess of incoherent garbled nonsense.***

While I’m not denigrating Barthes’ thought, it’s instructive to compare Barthes’ Camera Lucida with Susan Sontag’s On Photography, written about the same time. Where Barthes is maddeningly opaque – he speaks of “the wound” of the punctum, the “Dearth-of-Image,” the “Totality of Image,” i.e. the usual jargonist clap-trap – Sontag, good practical, American intellectual she is, gets to her point clearly and concisely, absent in-group jargon, seemingly without the need legitimize her thought by unnecessarily obfuscating it.

*************

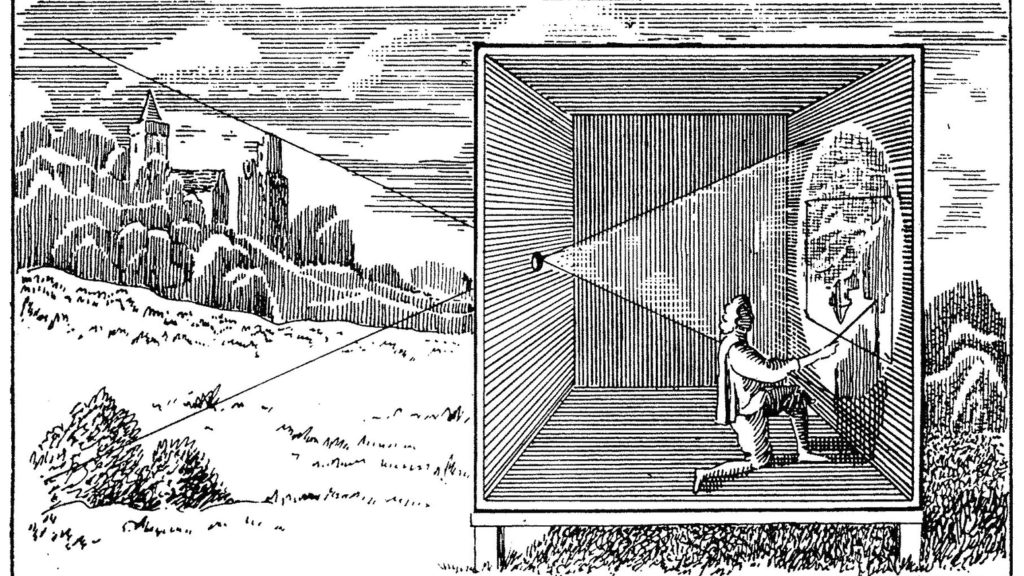

The Camera Obscura, Predecessor of the Photographic Camera

The question I posed at the end of Part One was this: What, if any, are the implications of Barthes’ ideas, as expressed in Camera Lucida, for ‘post-analog’ (i.e digital) photography? After posing the question, I then suggested the answer should be fairly obvious. As I see it, it’s this: Digital capture has severed the direct connection between the thing photographed and the resulting photo. “Photography” as commonly practiced today no longer possesses the one characteristic that made it unique among communicative media – its “Indexical,” as opposed to its “Iconic” relationship with what is real, what’s actually out there.** As such, you could argue it isn’t even “photography” anymore as the term is understood etymologically, but rather a new species of graphic arts. [Years ago, when I was naive enough to think that one could actually intelligently discuss issues like this on the net, I suggested this on a popular photography forum, whereupon forum “mentors” chortled at such  ridiculousness (one “mentor” – a retired insurance salesman who mentors readers on the intricacies of varoius camera bags – opined that only an idiot could think such ludicrous things), forum members pointed at me and laughed, moderators’ heads exploded, and shortly after I was summarily banned, for life, no possibility of reprieve, banished to the nether regions of web-based photographic discourse. My response? I started Leicaphilia.]

ridiculousness (one “mentor” – a retired insurance salesman who mentors readers on the intricacies of varoius camera bags – opined that only an idiot could think such ludicrous things), forum members pointed at me and laughed, moderators’ heads exploded, and shortly after I was summarily banned, for life, no possibility of reprieve, banished to the nether regions of web-based photographic discourse. My response? I started Leicaphilia.]

At the time Barthes wrote, when photography was the result of analog processes identical to those of the camera obscura (see above), we could rightfully assume that a photo necessarily dealt in the real and was more or less faithful evidence of the real. While someone could manipulate an analog photograph to a certain extent, the exception proved the basic rule: photography, in the words of Susan Sontag, was the stenciling off of the real. It was “evidence” of the real. For Barthes, that’s what makes photography absolutely unique as a medium of communication, Its very essence as a medium.

Digital capture doesn’t “stencil off” anything; rather, it turns everything into computer code which then needs to be reconstituted by more computer code. The “digital revolution” isn’t about simply providing more efficient photographic tools; rather, it’s a profound revolution of how we recreate the visual with similarly profound implications for its claim to being “true” by simply being. Unlike the photographic processes Barthes analyzed, digital processes de-materialize everything into non-material 1’s and 0’s ephemerally housed in computer “memory,” data that must then wait for an algorithm to reconstitute it “realistically” or transmogrify it into anything else imaginable, dependent upon the intentions of the algorithm’s creator. Need to make your selfie more sexually attractive, your landscape more picturesque? Need to remove an ex from a family portrait? There’s a “filter” (i.e. a certain computer algorithm designed to translate the latent data a certain way to acheive a certain pre-determined result) for that. Hell, those 1’s and 0’s that constitute the RAW file, or the DNG or the JPG, can just as easily be output as music if that’s your desire, the point being that the guarantee of indexicality that Barthes sees as exclusive to photography is a thing of the past. To quote Wim Wenders: “The digitized picture has broken the relationship between picture and reality once and for all. We are entering an era when no one will be able to say whether a picture is true or false. They are all becoming beautiful and extraordinary, and with each passing day, they belong increasingly to the world of advertising. Their beauty, like their truth, is slipping away from us. Soon they will really end up making us blind.”

The blind already exist. They’re the smug enthusiasts who think an interest in “photography” only means better cameras with greater resolution, easier capture and hassle-free output, who would dismiss those like Wenders who recognize something more profound at play while they simultaneously embrace – no, celebrate – the technologies undermining and ultimately destroying photography itself.

**Indexical Signs = signs where the signifier is caused by the signified, e.g., light enters a camera lens, is focused on a silver halide substance, and produces a negative via a photochemical process. Iconic signs = signs where the signifier resembles but is not directly caused by the signified, e.g., a digital “photo”, wherein the “photo” has no direct causation by the signified and thus can only be said to “resemble” the signified.

*** For an example of what passes for intelligent discourse in Semiotics, this from the Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, literally opened at random :

The phenotext is constantly split up and divided, and is irreducible to the semiotic process that works through the genotext. The phenotext is a structure (which can be generated, in generative grammar’s sense); it obeys rules of communication and presupposes a subject of enunciation and an addressee. The genotext, on the other hand, is a process; it moves through zones that have relative and transistory borders and constitutes a path that is not restricted to the two poles of univocal information between two full-fledged subjects.

To create your very own post-modernist essay, go here and click on the generator at the top of the page.