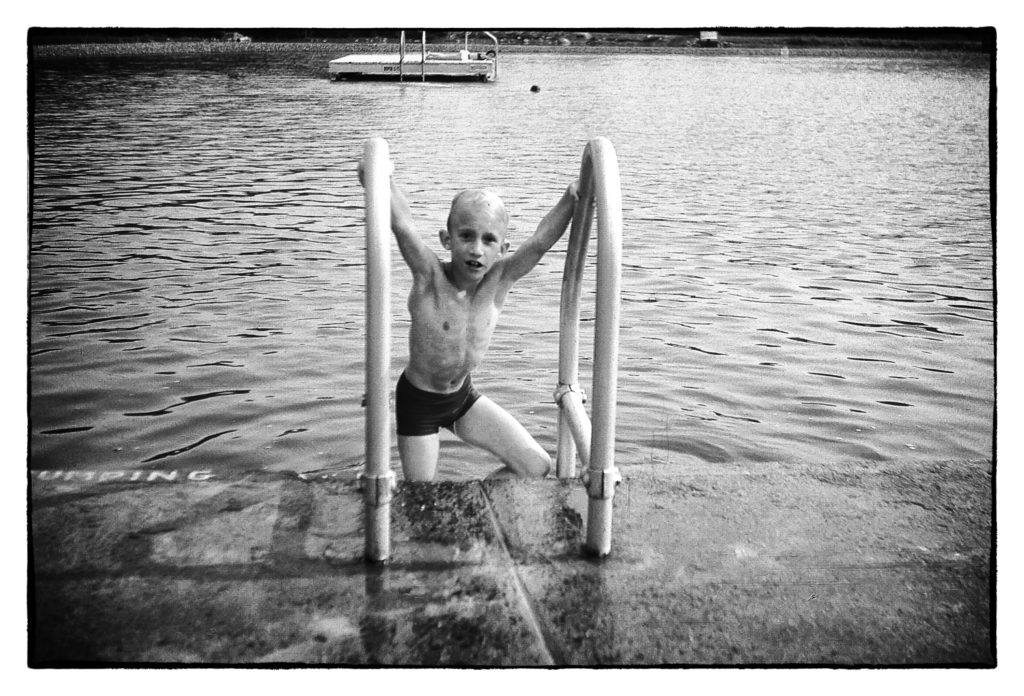

Let’s Call this “Self-Portrait, 1966″.

As you probably can tell by all the references I’ve recently made to German philosopher Martin Heidegger (1899-1976), I’ve had the misfortune of reading him at some length in the past few years. (Try reading Being and Time on your day off and you’ll better understand what I mean). I say ‘misfortune’ because he’s pretty much unreadable, obtuseness being part of his philosophical schtick, his assurance to you that he’s telling you something deep and profound if only you’re smart enough to understand.

Heidegger did say some important things, evident by his continued relevance in current academic discourse, even if, in addition to being unreadable, he was an odious fascist who embraced Nazism and flourished under it. Specifically, for our purposes, some interesting things to say about the visual artist and art, about the artist’s need for ‘authenticity’ and the process of self-definition creative pursuits offer us. [Remember: you as a photographer are a ‘visual artist’, so all of this applies to you].

Heidegger is considered an ‘Existentialist’, which, in addition to requiring you to sit in Parisian cafes and expound radical political theories, requires your belief that you don’t have any fixed nature but make yourself up as you go along i.e. there’s no such thing as ‘human nature’; you get to define yourself any way you want. For Heidegger, you are a ‘self-interpreting being’ who makes yourself what you are in the course of the activity of your life. To be human is to be an Artist of yourself.

Heidegger sees your ‘Art’ – the self-conscious practice of creating palpable expressions of your inner being i.e. you taking photos- as a part of the process of self-construction that constitutes your life. Heidegger is pointing to the immense importance of creative activities in the process of you being human. The process of creating ‘Art’ i.e. palpable things like novels or paintings or photographs – is distinct from, yet part of, that larger creative act that is your being. Think of your art as permanently fixed creative action, a temporal snapshot – a slice of life – you take from the larger evolving creative process that is your lived life.

*************

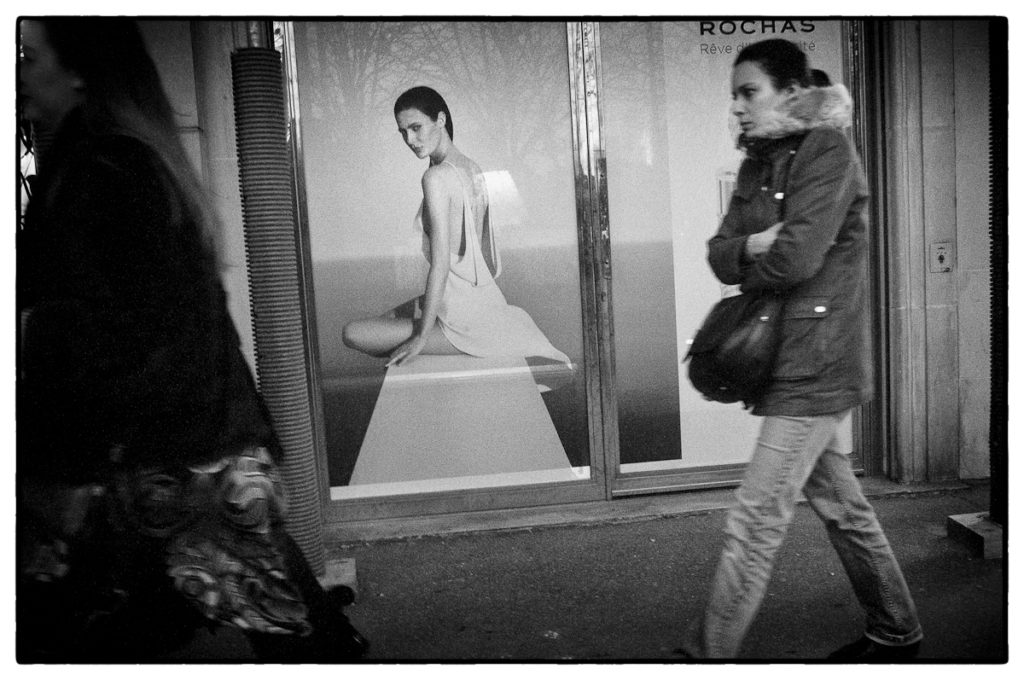

Susan, Cape Cod. Me Looking at Her Looking at Me – A Perfect Visual Encapsulation of Heidegger’s Theory of Self

We aren’t alone in this process of creating ourselves. In Heidegger’s view, our being is also defined by the world into which we are “thrown.” Your identity is only possible in what Heidegger calls “shared forms of life” in a “public life world.” There’s no you without the context provided by others, the world you didn’t choose but rather are thrown into. If this is true it introduces a certain serendipity into your supposed ‘self-creation’; you are responsible for creating yourself, yes, but your ability to do so is circumscribed in some sense by the existential realities of others. Insofar as your palpable creations are concerned i.e. your photos, they are the creations of an interactive process that presupposes a third party, the recipient of your work – the viewer, the critic – as a necessary part of the process by which you create yourself. If your art is a formative exchange between you and your work, Heidegger also understands it as a formative exchange between your work and others, and this dynamic is as much a part of the artwork as is your relationship to the work.

Post-Heideggerian heavy thinkers like Merleau-Ponty, Hans-Georg Gadamer and Paul Ricoeur share this ‘dialectical’ concept of truth in art. Only through this dialogue with your work and with others through your work can you authentically express yourself. The ‘meaning’ of an artwork is the sum of dialogue of differing viewpoints brought to the exchange, both spoken and unspoken, between you, and its viewer. What others think about your work matters to you.

*************

Philosophical speculation can be fascinating. Often, though, I find myself wondering whether a given philosopher’s thought mirrors reality rather than an elaborately spun intellectual puzzle. Is Heidegger correct? Are we really somehow defined by how others see us? Are we at the mercy of other’s understanding of what we’re doing? Does it really matter what others say of our self-expression? If so, it seems to compromise the very premise of Heidegger’s notion of art as self-construction. How is it ‘me creating myself through my life and my artistic decisions’ if my truth, my definition, is also dependent on your understanding? How could you possibly participate in my own self-definition? Seems a contradiction in terms.

I don’t buy it. If my photography is a form of ‘self-creation’ I shouldn’t need input into what I’m doing. I’m doing it for me, not you, and it needs to make sense to me and if it does it doesn’t matter to me if it makes sense to you. It’s why I’ve often resisted showing my work in public. I can’t remember ever getting a comment or critique that helped me understand what I was doing. It’s why photo competitions and portfolio critiques seem deflections of creative energy, and at worst, self-destructive. It’s the off-loading of creative responsibility on others, or, at the least, a refusal to take responsibility for your creative autonomy.

Critique my work all you want, it’s your right. I’m glad it’s out there and possibly a small piece in what helps you achieve your own self-definition. But don’t confuse your critique with something that’s going to aid me on my own creative path. You can’t know. You don’t have that power…unless I cede it to you, and if I cede it you, I’m abdicating my own responsibility for self-definition.

The bottom line: use your photography in a way that makes sense to you. Stop apeing others and create photos that have meaning for you. Forget the ‘shoulds’ that others always seem to want to impose on what is a uniquely personal and singular quest. Allow others to do the same. Each of us, in exercising our creative capacities is building a self. Build the self that works for you.