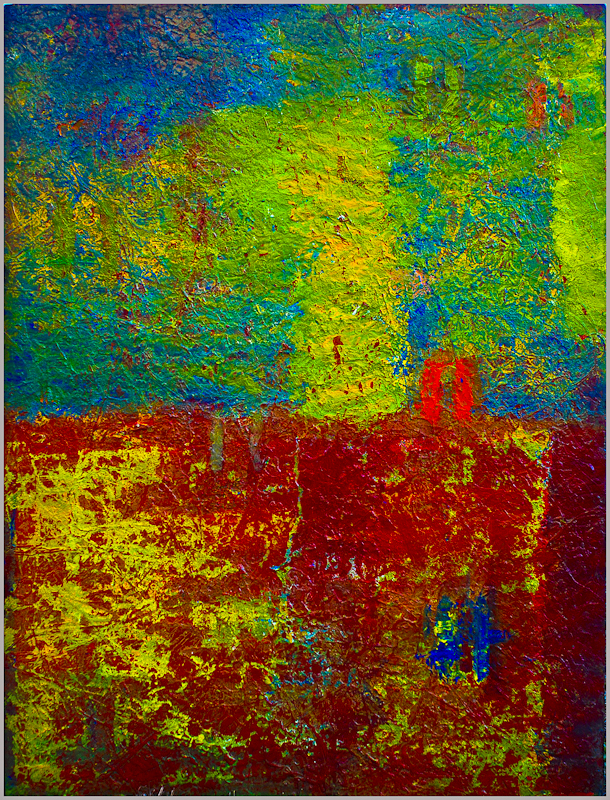

Took this in 1976. Still Love It, Because it Says Something to Me. Bonus Points: What’s the Punctum?

As I’ve mentioned before, I became a ‘painter’ for a while. I’d had no formal training, nor did I really know much about the history of painting as a representational or creative medium apart from having read about Carravagio and Picasso and van Gogh and Pollock. I knew what I was supposed to like, what I actually liked (van Gogh and Pollock!) and that was about it. Some of my photos hung in a gallery that also represented the Macedonian abstract painter Robert Cvetkovski, and it happened that he needed a place to stay while hosting a major exhibition of his work here in North Carolina, so he stayed with me for a few months. I watched him work and, being bored, decided to take a canvas and try to paint in a similar non-representative fashion. Hell, I thought, if he could do it, so could I. So I did, and, in my initial flush of excitement, foolishly thought I wasn’t bad at all. In fact, I talked the gallery owner into giving me a show, at which a pleasant, enthusiastic couple stood with me in front of one of my paintings and inquired as to my creative influences. It was at that moment I realized I was a poseur.

Basically, being the dummy I was (am) – and leaving aside the larger question of the Macedonian guy and his authenticity – I foolishly ignored the vast functional difference between what I was doing and what those did who created the genre of abstract painting, artists who sought to express deep convictions about life, emotion, and experience through what they knew about color, line, shape, and representation. My paintings of drips and blobs and primitive shapes – sometimes quite visually appealing – weren’t really art, because they weren’t authentic to me. They were, at best, decoration, which is what I see them as now, with the benefit of hindsight. I was mimicking creating ‘Art’, appropriating the symbols and modes of expression of others. I was a poseur.

Untitled, 2005. At Least I Didn’t Title it “Metaphysical Daydream Part 14“.

This concept of ‘authenticity’ provides us a way to differentiate legitimate art or action from those that merely pretend (the ‘pretentious’), those done in what Jean-Paul Sarte calls ‘bad faith’ – modes of expression not true to the artist or actor’s essential individuality. Authenticity is about using a form of expression that comes from within, not merely appropriating someone else’s form of expression. As long as what you’re doing is expressing who you are as opposed to signaling who you admire or who you think you should be to impress others, you’re not a poseur.

*************

Being true to your essential creative nature, as opposed to apeing other’s, can be frightening; you’re exposing the most vital part of yourself to other’s critical judgments, and other people can be clueless, mean, judgmental pricks [guilty as charged]. Sartre claimed that exposing your real self to the gaze of others could be so overwhelming it could cause mental, emotional and physical distress, what he referred to as “nausea.” Yet he saw this profound discomfort as necessary if you were going to be true to yourself ***. This was the price of being authentic. Sartre saw it as a process driven by discomfort, where to be true to your inner calling happened when the psychic embarrassment in being inauthentic became greater than the discomfort of expressing something true to yourself, in effect putting you out there for others to observe and critique. And that’s what happened to me: after that period of painting in ‘bad faith,’ after the profound internal embarrassment of standing in front of my work mouthing inauthentic babble about what ‘it meant,’ I made a decision to abandon the idea that my output needed to please or impress anyone but me…and in the process became a much better photographer and painter.

All this doesn’t mean you have to be completely unique, without influences – sui generis – to be authentic. I certainly have influences that show in my work. That’s the nature of creative expression – it always comes from antecedents that it can be linked to the current work and in some partial way help explain it without exhausting its meaning. Look at Trent Parke, the guy whose video I previously posted; if you’re a photography aficionado, you can see his influences, but those influences don’t define him. He’s added something to make what he creates his own. Likewise, it doesn’t mean you can’t be commercially successful. It doesn’t require you laboring in anonymity or critical irrelevance, trusting that someday someone will recognize you. It just means that you’ll need to ignore whatever commercial or critical pressures that encourage you to conform to anyone’s ultimate vision but your own.

Authenticity is the drive to achieve something from within, to create work you know feels ‘right’ as opposed to work that appeals to other’s sense of right. It manifests itself in devotion to your unique vision backed up with hard work to achieve it, the ultimate irony being that authentic expression usually appears effortless and belies the amount of work invested, while the inauthentic gives the unmistakable impression of “trying too hard.” The “Train Guy,” the guy I was critiquing a few posts ago, he’s trying way too hard.

*** Which begs the question: how can Sartre talk about being authentic when his entire philosophy is premised on the claim that we have no ‘true’ self but rather that we make it up as we go along?