[Editor’s Note: In 1952, Henri Cartier-Bresson published Images à la Sauvette, (what is known in English as The Decisive Moment, although the French title translates as “Images on the run”). Images à la Sauvette included a portfolio of 126 of Cartier Bresson’s photos This is the book’s 4,500-word philosophical preface, written by Cartier Bresson himself]

*************

by Henri Cartier-Bresson (1952)

There is nothing in this world without a decisive moment. Cardinal Retz

I, like many another boy, burst into the world of photography with a Box Brownie, which I used for taking holiday snapshots. Even as a child, I had a passion for painting, which I “did” on Thursdays and Sundays, the days when French school children don’t have to go to school. Gradually, I set myself to try to discover the various ways in which I could play with a camera. From the moment that I began to use the camera and to think about it, however, there was an end to holiday snaps and silly pictures of my friends. I became serious. I was on the scent of something, and I was busy smelling it out.

Then there were the movies. From some of the great films, I learned to look, and to see. Mysteries of New York, with Pearl White; the great films of D.W. Griffith – Broken Blossoms; the first films of Stroheim; Greed; Eisenstein’s Potemkin; and Dreyer’s Jeanne d’ Arc – these were some of the things that impressed me deeply.

Later I met photographers who had some of Atget’s prints. These I considered remarkable and, accordingly, I bought myself a tripod, a black cloth, and a polished walnut camera three by four inches. The camera was fitted with – instead of a shutter – a lenscap, which one took off and then put on to make the exposure. This last detail, of course, confined my challenge to the static world. Other photographic subjects seemed to me to be too complicated, or else to be “amateur stuff.” And by this time I fancied that by disregarding them, I was dedicating myself to Art with a capital “A.”

Next I took to developing this Art of mine in my washbasin. I found the business of being a photographic Jack-of-All-Trades quite entertaining. I knew nothing about printing, and had no inkling that certain kinds of paper produced soft prints and certain others highly contrasted ones. I didn’t bother much about such things, though I invariably got mad when the images didn’t come out right on the paper.

In 1931, when I was twenty-two, I went to Africa. On the Ivory Coast I bought a miniature camera of a kind I have never seen before or since, made by the French firm Krauss. It used film of a size that 35mm would be without the sprocket holes. For a year I took pictures with it. On my return to France I had my pictures developed – it was not possible before, for I lived in the bush, isolated, during most of that year – and I discovered that the damp had got into the camera and that all my photographs were embellished with the superimposed patterns of giant ferns.

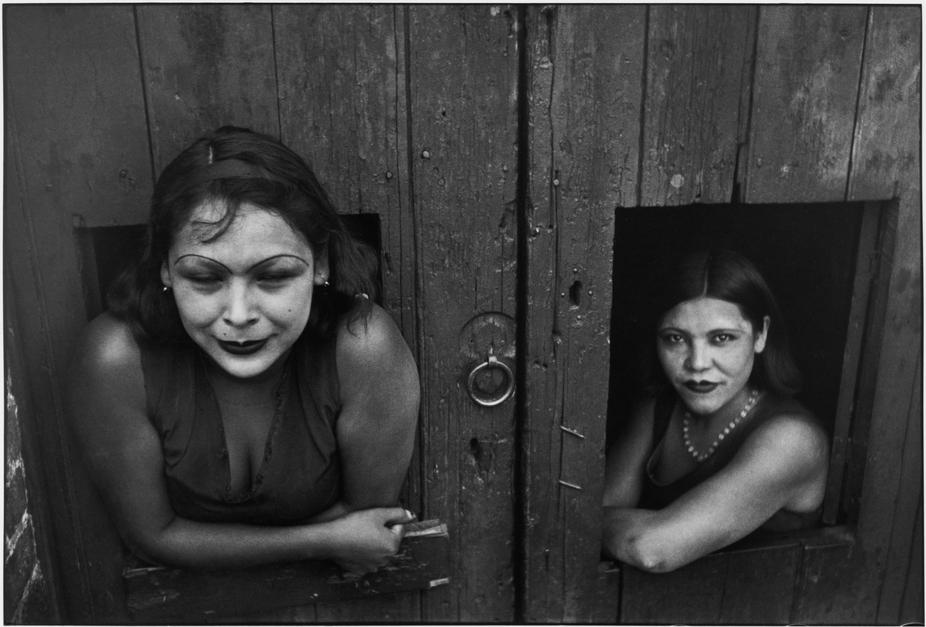

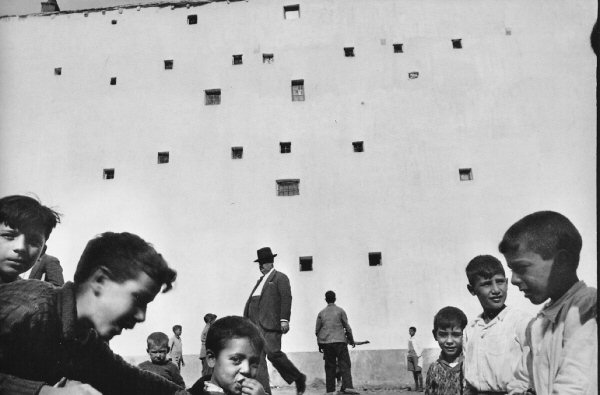

I had had blackwater fever in Africa, and was now obliged to convalesce. I went to Marseille. A small allowance enabled me to get along, and I worked with enjoyment. I had just discovered the Leica. It became the extension of my eye, and I have never been separated from it since I found it. I prowled the streets all day, feeling very strung-up and ready to pounce, determined to “trap” life – to preserve life in the act of living. Above all, I craved to seize, in the confines of one single photograph, the whole essence of some situation that was in the process of unrolling itself before my eyes.

The idea of making a photographic reportage, that is to say, of telling a story in a sequence of pictures, never entered my head at that time. I began to understand more about it later, as a result of looking at the work of my colleagues and at the illustrated magazines. In fact, it was only in the process of working for them that I eventually learned, bit by bit, how to make a reportage with a camera, how to make a picture-story.

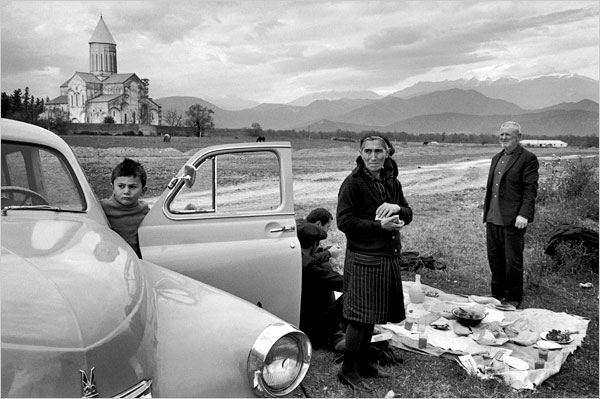

I have traveled a good deal, though I don’t really know how to travel. I like to take my time about it, leaving between one country and the next an interval in which to digest what I’ve seen. Once I had arrived in a new country, I feel almost like settling down there, so as to live on proper terms with the country. I could never be a globetrotter.

In 1947, five freelance photographers, of whom I was one, founded our cooperative enterprise called “Magnum Photos.” This cooperative enterprise distributes our picture- stories to magazines in various countries.

Twenty-five years have passed since I started to look through my view-finder. But I regard myself still as an amateur, though I am still no longer a dilettante.

*************

The Picture Story

What actually is a photographic reportage, a picture story? Sometimes there is one unique picture whose composition possesses such vigor and richness, and whose content so radiates outward from it, that this single picture is a whole story in itself. But this rarely happens. The elements which, together, can strike sparks from a subject, are often scattered – either in terms of space or time – and bringing them together by force is “stage management,” and, I feel, contrived. But if it is possible to make pictures of the “core” as well as the struck-off sparks of the subject, this is a picture-story. The page serves to reunite the complementary elements which are dispersed throughout several photographs.

The picture-story involves a joint operation of the brain, the eye and the heart. The objective of this joint operation is to depict the content of some event which is in the process of unfolding, and to communicate impressions. Sometimes a single event can be so rich in itself and its facets that it is necessary to move all around it in your search for the solution to the problems it poses – for the world is movement, and you cannot be stationary in your attitude toward something that is moving. Sometimes you light upon the picture in seconds; it might also require hours or days. But there is no standard plan, no pattern from which to work. You must be on the alert with the brain, the eye, the heart, and have a suppleness of body.

Things-As-They-Are offer such an abundance of material that a photographer must guard against the temptation of trying to do everything. It is essential to cut from the raw material of life – to cut and cut, but to cut with discrimination. While working, a photographer must reach a precise awareness of what he is trying to do. Sometimes you have the feeling that you have already taken the strongest possible picture of a particular situation or scene; nevertheless, you find yourself compulsively shooting, because you cannot be sure in advance exactly how the situation, the scene, is going to unfold. You must stay with the scene, just in case the elements of the situation shoot off from the core again. At the same time, it’s essential to avoid shooting like a machinegunner and burdening yourself with useless recordings which clutter your memory and spoil the exactness of the reportage as a whole.

Memory is very important, particularly in respect to the recollection of every picture you’ve taken while you’ve been galloping at the speed of the scene itself. The photographer must make sure, while he is still in the presence of the unfolding scene, that he hasn’t left any gaps, that he has really given expression to the meaning of the scene in its entirety, for afterward it is too late. He is never able to wind the scene backward in order to photograph it all over again.

For photographers:, there are two kinds of selection to be made, and either of them can lead to eventual regrets. There is the selection we make when we look through the view-finder at the subject; and there is the one we make after the tiles have been developed and printed. After developing and printing, you must go about separating the pictures which, though they are all right, aren’t the strongest. When it’s too late, then you know with a terrible clarity exactly where you failed; and at this point you often recall the telltale feeling you had while you were actually making the pictures. Was it a feeling of hesitation due to uncertainty? Was it because of some physical gulf between yourself and the unfolding event? Was it simply that you did not take into account a certain detail in relation to the whole setup? Or was it (and this is more frequent) that your glance became vague, your eye wandered off?

For each of us space begins and slants off from our own eye, and from there enlarges itself progressively toward infinity. Space, in the present, strikes us with greater or lesser intensity and then leaves us, visually, to be closed in our memory and to modify itself there. Of all the means of expression, photography is the only one that fixes forever the precise and transitory instant. We photographers deal in things that are continually vanishing, and when they have vanished, there is no contrivance on earth that can make them come back again. We cannot develop and print a memory. The writer has time to reflect. He can accept and reject, accept again; and before committing his thoughts to paper he is able to tie the several relevant elements together. There is also a period when his brain “forgets,” and his subconscious works on classifying his thoughts. But for photographers, what has gone is gone forever. From that fact stem the anxieties and strength of our profession. We cannot do our story over again once we’ve got back to the hotel. Our task is to perceive reality, almost simultaneously recording it in the sketchbook which is our camera. We must neither try to manipulate reality while we are shooting, nor manipulate the results in a darkroom. These tricks are patently discernible to those who have eyes to see.

In shooting a picture-story we must count the points and the rounds, rather like a boxing referee. In whatever picture-story we try to do, we are bound to arrive as intruders. It is essential,

therefore, to approach the subject on tiptoe – even if the subject is still-life. A velvet hand, a hawk’s eye – these we should all have. It’s no good jostling or elbowing. And no photographs taken with the aid of flashlight either, if only out of respect of the actual light – even when there isn’t any of it. Unless a photographer observes such conditions as these, he may become an intolerably aggressive character.

The profession depends so much upon the relations the photographer establishes with the people he’s photographing, that a false relationship, a wrong word or attitude, can ruin everything. When the subject is in any way uneasy, the personality goes away where the camera can’t reach it. There are no systems, for each case is individual and demands that we be unobtrusive, though we must be at close range. Reactions of people differ much from country to country, and from one social group to another. Throughout the whole of the Orient, for example, an impatient photographer – or one who is simply pressed for time – is subject to ridicule. If you have made yourself obvious, even just by getting your light-meter out, the only thing to do is to forget about photography for the moment, and accommodatingly allow the children who come rushing at you to cling to your knees like burrs.

*************

The Subject

There is subject in all that takes place in the world, as well as in our personal universe. We cannot negate subject. It is everywhere. So we must be lucid toward what is going on in the world, and honest about what we feel.

Subject does not consist of a collection of facts, for facts in themselves offer little interest. Through facts, however, we can reach an understanding of the laws that govern them, and be better able to select the essential ones which communicate reality.

In photography, the smallest thing can be a great subject. The little, human detail can become a leitmotiv. We see and show the world around us, but it is an event itself which provokes the organic rhythm of forms.

There are thousands of ways to distill the essence of something that captivates us; let’s not catalogue them. We will, instead, leave it in all its freshness…

There is a whole territory which is no longer exploited by painting. Some say it is because of the discovery of photography. However it came about, photography has taken over a part of this territory in the form of illustration.

One kind of subject matter greatly derided by present- day painters is the portrait. The frock coat, the soldier’s cap, the horse now repel even the most academic of painters. They feel suffocated by all the gaiter buttons of the Victorian portrait makers. For photographers – perhaps because we are reaching for something much less lasting in value than the painters – this is not so much irritating as amusing, because we accept life in all its reality.

People have an urge to perpetuate themselves by means of a portrait, and they put their best profiles forward for posterity. Mingled with this urge, though, is a certain fear of black magic; a feeling that by sitting for a camera portrait they are exposing themselves to the workings of witchcraft of a sort.

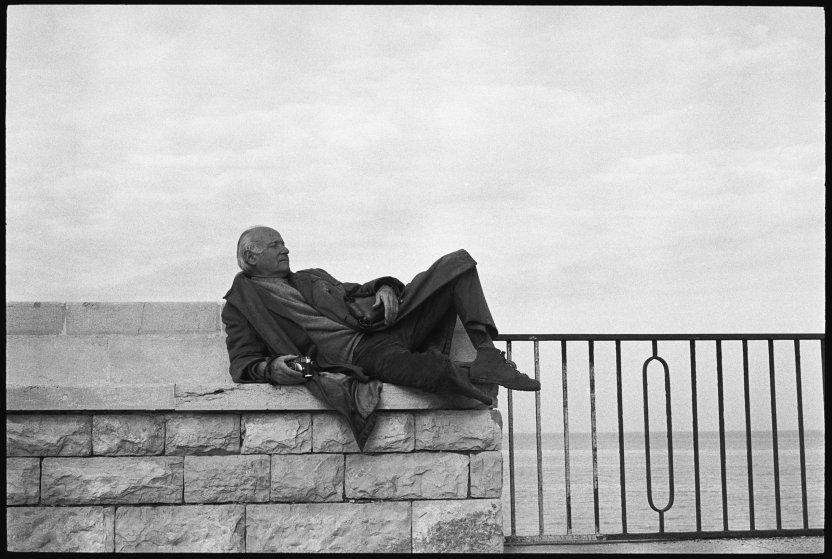

One of the fascinating things about portraits is the way they enable us to trace the sameness of man. Man’s continuity somehow comes through all the external things that constitute him – even if it is only to the extent of someone’s mistaking Uncle for Little Nephew in the family album. If the photographer is to have a chance of achieving a true reflection of a person’s world – which is as much outside him as inside him – it is necessary that the subject of the portrait should be in a situation normal to him. We must respect the atmosphere which surrounds the human being, and integrate into the portrait the individual’s habitat – for man, no less than animals, has his habitat. Above all, the sitter must be made to forget about the camera and the photographer who is handling it. Complicated equipment and light reflectors and various other items of hardware are enough, to my mind, to prevent the birdie from coming out.

What is there more fugitive and transitory than the expression on a human face? The first impression given by a particular face is often the right one; but the photographer should try always to substantiate the first impression by “living” with the person concerned. The decisive moment and psychology, no less than camera position are the principal factors in the making of a good portrait. It seems to me it would be pretty difficult to be a portrait photographer for customers who order and pay since, apart from a Maecenas or two, they want to be flattered, and

the result is no longer real. The sitter is suspicious of the objectivity of the camera, while the photographer is after an acute psychological study of the sitter.

It is true, too, that a certain identity is manifest in all the portraits taken by one photographer. The photographer is searching for identity of his sitter, and also trying to fulfill an expression of himself. The true portrait emphasizes neither the suave nor the grotesque, but reflects the personality.

I infinitely prefer, to contrived portraits, those little identity-card photos which are pasted side by side, row after row, in the windows of passport photographers. At least there is on these faces something that raises a question, a simple factual testimony – this in place of the poetic identification we look for.

Composition

*************

If a photograph is to communicate its subject in all its intensity, the relationship of form must be rigorously established. Photography implies the recognition of a rhythm in the world of real things. What the eye does is to find and focus on the particular subject within the mass of reality; what the camera does is simply to register upon film the decision made by the eye. We look at and perceive a photograph, as we do a painting, in its entirety and all in one glance. In a photograph, composition is the result of a simultaneous coalition, the organic coordination of elements seen by the eye. One does not add composition as though it were an afterthought superimposed on the basic subject material, since it is impossible to separate content from form. Composition must have its own inevitability about it.

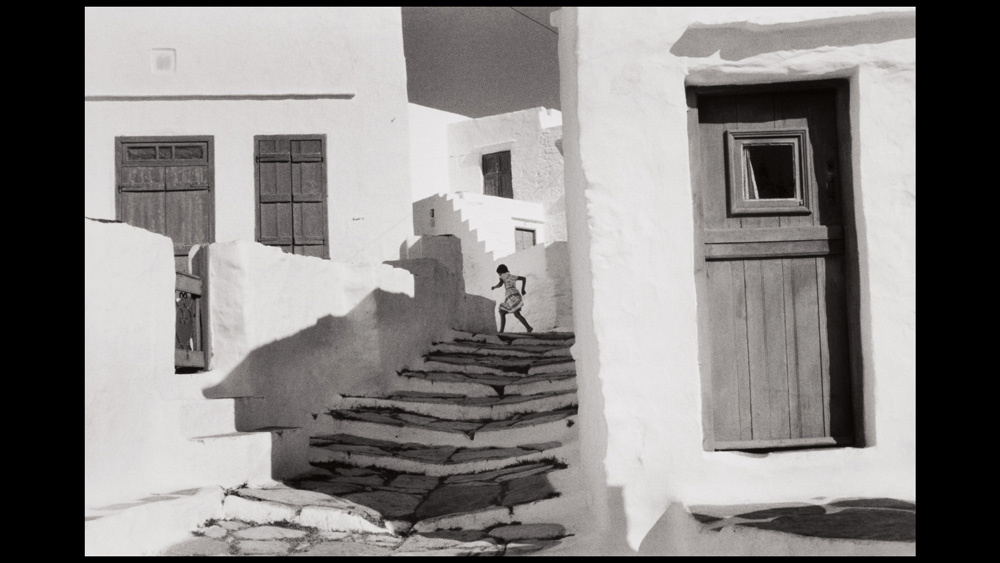

In photography there is a new kind of plasticity, the product of instantaneous lines made by movements of the subject. We work in unison with movement as though it were a presentiment of the way in which life itself unfolds. But inside movement there is one moment at which the elements in motion are in balance. Photography must seize upon this moment and hold immobile the equilibrium of it.

The photographer’s eye is perpetually evaluating. A photographer can bring coincidence of line simply by moving his head a fraction of a millimeter. He can modify perspectives by a slight bending of the knees. By placing the camera closer to or farther from the subject, he draws a

detail – and it can be subordinated, or he can be tyrannized by it. But he composes a picture in very nearly the same amount of time it takes to click the shutter, at the speed of a reflex action.

Sometimes it happens that you stall, delay, wait for something to happen. Sometimes you have the feeling that here are all the makings of a picture – except for just one thing that seems to be missing. But what one thing? Perhaps someone suddenly walks into your range of view. You follow his progress through the viewfinder. You wait and wait, and then finally you press the button – and you depart with the feeling (though you don’t know why) that you’ve really got something. Later, to substantiate this, you can take a print of this picture, trace on it the geometric figures which come up under analysis, and you’ll observe that, if the shutter was released at the decisive moment, you have instinctively fixed a geometric pattern without which the photograph would have been both formless and lifeless.

Composition must be one of our constant preoccupations, but at the moment of shooting it can stem only from our intuition, for we are out to capture the fugitive moment, and all the interrelationships involved are on the move. In applying the Golden Rule, the only pair of compasses at the photographer’s disposal is his own pair of eyes. Any geometrical analysis, any reducing of the picture to a schema, can be done only (because of its very nature) after the photograph has been taken, developed, and printed – and then it can be used only for a postmortem examination of the picture. I hope we will never see the day when photo shops sell little schema grills to clamp onto our viewfinders; and the Golden Rule will never be found etched on our ground glass.

If you start cutting or cropping a good photograph, it means death to the geometrically correct interplay of proportions. Besides, it very rarely happens that a photograph which was feebly composed can be saved by reconstruction of its composition under the darkroom’s enlarger; the integrity of vision is no longer there. There is a lot of talk about camera angles; but the only valid angles in existence are the angles of the geometry of composition and not the ones fabricated by the photographer who falls flat on his stomach or performs other antics to procure his effects.

Color In talking about composition we have been so far thinking only in terms of that symbolic color called black. Black-and-white photography is a deformation, that is to say, an abstraction. In it, all the values are transposed; and this leaves the possibility of choice.

Color photography brings with it a number of problems that are hard to resolve today, and some of which are difficult even to foresee, owing to its complexity and its relative immaturity. At present [1952], color film emulsions are still very slow. Consequently, photographers using color have a tendency to confine themselves to static subjects; or else to use ferociously strong artificial lights. The slow speed of color film reduces the depth of focus in the field of vision in relatively close shots; and this cramping often makes for dull composition. On top of that, blurred backgrounds in color photographs are distinctly displeasing.

Color photographs in the form of transparencies seem quite pleasing sometimes. But then the engraver takes over; and a complete understanding with the engraver would appear to be as desirable in this business as it is in lithography. Finally, there are the inks and the paper, both of which are capable of acting capriciously. A color photograph reproduced in a magazine or semiluxury edition sometimes gives the impression of an anatomical dissection which has been badly bungled.

It is true that color reproductions of pictures and documents have already achieved a certain fidelity to the original; but when the color proceeds to take on real life, it’s another matter. We are only in the infancy of color photography. But all this is not to say we should take no further interest in the question, or sit by waiting for the perfect color film – packaged with the talent necessary to use it – to drop into our laps. We must continue to try to feel our way.

Though it is difficult to foresee exactly how color photography is going to grow m photoreporting, it seems certain that it requires a new attitude of mind, an approach different than that which is appropriate for black-and-white. Personally, I am half afraid that this complex new element may tend to prejudice the achievement of the life and movement which is often caught by black-and-white. To really be able to create in the field of color photography, we should transform and modulate colors, and thus achieve liberty of expression within the framework of the laws which were codified by the Impressionists and from which even a photographer cannot shy away. (The law, for instance, of simultaneous contrast: the law that every color tends to tinge the space next to it with its complementary color; that it two tones contain a color which is common to them both, that common color is attenuated by placing the two tones side by side; that two complementary colors placed side by side emphasize both, but mixed together they annihilate each other; and so on.)

The operation of bringing the color of nature in space to a printed surface poses a series of extremely complex problems. To the eye, certain colors advance, others recede. So we would have to be able to adjust the relations of the color one to the other, for colors, which in nature place themselves in the depth of space, claim a different placing on a plane surface – whether it is the flat surface of a painting or a photograph.

The difficulties involved in snapshooting are precisely that we cannot control the movement of the subject; and in color-photography reporting, the real difficulty is that we are unable to control the interrelation of colors within the subject. It wouldn’t be hard to add to the list of difficulties involved, but it is quite certain that the development of photography is tied up with the development of its technique.

*************

Technique

Constant new discoveries in chemistry and optics are widening our field of action considerably. It is up to us to apply them to our technique, to improve ourselves, but there is a whole group of fetishes which have developed on the subject of technique.

Technique is important only insofar as you must master it in order to communicate what you see. Your own personal technique has to be created and adapted solely in order to make your vision effective on film. But only the results count, and the conclusive evidence is the finished photographic print; otherwise there would be no end to the number of tales photographers would tell about pictures which they ever-so-nearly got – but which are merely a memory in the eye of the nostalgia.

Our trade of photo-reporting has been in existence only about thirty years. It came to maturity due to the development of easily handled cameras, faster lenses, and fast fine-grain films produced for the movie industry. The camera is for us a tool, not a pretty mechanical toy. In the precise functioning of the mechanical object perhaps there is an unconscious compensation for the anxieties and uncertainties of daily endeavor. In any case, people think far too much about techniques and not enough about seeing.

It is enough if a photographer feels at ease with his camera, and if it is appropriate to the job he wants it to do. The actual handling of the camera, its stops, its exposure-speeds and all the rest of it are things which should be as automatic as the changing of” gears in an automobile. It is no part of my business to go into the details or refinements of any of these operations, even the most complicated ones, for they are all set forth with military precision in the manuals which the manufacturers provide along with the camera and the nice orange calf-skin case. If the camera is a beautiful gadget, we should progress beyond that stage at least in conversation. The same applies to the hows and whys of making pretty prints in the darkroom.

During the process of enlarging, it is essential to re-create the values and mood of the time the picture was taken; or even to modify the print so as to bring it into line with the intentions of the photographer at the moment he shot it. It is necessary also to re-establish the balance which the eye is continually establishing between light and shadow. And it is for these reasons that the final act of creating in photography takes place in the darkroom.

I am constantly amused by the notion that some people have about photographic technique – a notion which reveals itself in an insatiable craving for sharpness of images. Is this the passion of an obsession? Or do these people hope, by this trompe l’ oeil technique, to get to closer grips with reality? In either case, they are just as far away from the real problem as those of that other generation which used to endow all its photographic anecdotes with an intentional unsharpness such as was deemed to be “artistic”.

*************

The Customers

The camera enables us to keep a sort of visual chronicle. For me, it is my diary. We photoreporters are people who supply information to a world in a hurry, a world weighted down with preoccupations, prone to cacophony, and full of beings with a hunger for information and needing the companionship of images. We photographers, in the course of taking pictures, inevitably make a judgment on what we see, and that implies a great responsibility. We are, however, dependent on printing, since it is to the illustrated magazines that we, as artisans, deliver raw material.

It was indeed an emotional experience for me when I sold my first photograph (to the French magazine Vu).That was the start of a long alliance with magazines. The magazines produce for us a public, and introduce us to that public; and they know how to get picture-stories across in the way the photographer intended. But sometimes, unhappily, they distort them. The magazine can publish exactly what the photographer wanted to show; but the photographer runs the risk of letting himself be molded by the taste or the requirements of the magazine.

In a picture-story, the captions should invest the pictures with a verbal context, and should illuminate whatever relevant thing it may have been beyond the power of camera to reach. Unfortunately, in the sub-editor’s room, mistakes sometimes slip in that are not just simple misspellings or malapropisms. For these mistakes the reader often holds the photographer responsible. Such things do happen.

The pictures pass through the hands of the editor and the layout man. The editor has to make his choice from the thirty or so pictures of which the average picture-story consists. (It is rather as though he had to cut a text article to pieces in order to end up with a series of quotations!) For a picture-story, as for a novel, there are certain set forms. The pictures of the editor’s choice have to be laid out within the space of two, three, or four pages, according to the amount of interest he thinks they are likely to arouse, or according to the current state of paper shortage.

The great art of the layout man lies in his knowing how to pick from this pile of pictures the particular one which deserves a full-page or a double-page spread; in his knowing where to insert the small picture which must serve as an indispensable link in the story. (The photographer, when he is actually taking the pictures for his story, should never give a thought to the ways in which it will be possible to lay out those pictures to the most advantage.) The layout man will often have to crop one picture so as to leave only the most important section of it – since, for him, it is the unity of the whole page or of the whole spread that counts above all else. A photographer can scarcely be too appreciative of the layout man who gives his work a beautiful presentation of a kind which keeps the full import of the story; a display in which the pictures have spatially correct margins and stand out as they should; and in which each page possesses its own architecture and rhythm.

There is a third anguish for a photographer – when he looks for his story in a magazine. There are ways of communicating our photographs other than through publication in magazines.

Exhibitions, for instance; and the book form, which is almost a form of permanent exhibition.

I have talked at some length, but of only one kind of photography. There are many kinds. Certainly the fading snapshot carried in the back of a wallet, the glossy advertising catalog, and the great range of things in between are photography. I don’t attempt to define it for everyone. I only attempt to define it to myself;

To me, photography is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event as well as of a precise organization of forms which give that event its proper expression.

I believe that, through the act of living, the discovery of oneself is made concurrently with the discovery of the world around us, which can mold us, but which can also be affected by us. A balance must be established between these two worlds – the one inside us and the one outside us. As the result of a constant reciprocal process, both these worlds come to form a single one. And it is this world that we must communicate.

But this takes care only of the content of the picture. For me, content cannot be separated from form. By form, I mean a rigorous organization of the interplay of surfaces, lines, and values. It is in this organization alone that our conceptions and emotions become concrete and communicable. In photography, visual organization can stem only from a developed instinct.

Tim

Why did you change the lead photograph? It is one of my favorites.

The first shot, of the praying women above a valley, apparently was the one that drove David Bailey into serious photography.

HC-B does go on a bit; there’s not a little touch of my way or the highway about his writing which, of course, is not to contradict him, but to point out that there is more than one way of skinning the proverbial cat. Not, of course, that I have ever skinned a cat, though I did go through a very brief period where I skinned birds (dead ones).

In essence, what he says could be edited down to the simple fact that, still life specialists aside, the photographer’s eye has to multi-task very rapidly, totally on auto.

It’s become an almost universally known thing about HC-B that he loved to talk about geometry. That’s so much a rather grand way of saying design or composition, and for him, it did become yet another little personal tab of public reference along with decisive moment, though something rather out of focus in the back of my mind tells me the latter expression was actually lifted from someone else’s lexicon.

I don’t mean to belittle the man; he is one of my first heroes in his field and I did put my money down and buy, never regretting the book for a moment, unlike several other such purchases that annoy the hell out of me for acting on impulse.

Perhaps the reality of the thing is this: his piece, here, makes good introductory reading for the non-photographer, whereas for anybody else who has worked a camera for some time, it’s not telling us anything we haven’t already realised pretty quickly by ourselves.

But boy, his pictures are something else. We can work cameras all our lives and never get there.

Thanks for your efforts.

On the title, from the booklet that accompanies a later Steidl edition: Cartier-Bresson drew up a list of 45 title suggestions (in French). The first was “A pas de loup” (tiptoeing), the second, “Images a la sauvette.” This second one proved difficult to translate and the English title was ultimately extracted from the introduction. “Inspired by his French publisher, imposed by his American publisher, this expression did not belong to Cartier-Bresson…”

And “a la sauvette” doesn’t exactly translate to “on the run”. Closer would be “in haste”, but there is also a sense of “stolen”, and a hint of “just in time”, which I suppose is where “decisive” came from…

I think you’re close to the meaning. The french say a street vendor is selling “a la sauvette” or without a license, so there’s a sense of sneakiness.

Rob, skin or pluck a bird? In our home if you shot it, you cleaned it. That sure as heck convinced me to buy chicken from a butcher.

As for his holy highness H C-B, he made his own path, didn’t seek approval from anyone, and defined ‘cool.’ Wasn’t bad w/a Leica either.

Never did like his art, but he wouldn’t care.

No, mine were not edible birds. They were, on the whole, diminutive creatures the size of sparrows, only far more pretty, for which sin they fell prey to the airgun. This killer craze lasted a couple of weeks during a holiday at a schoolfriend’s tea estate up in the Nilgiris.

The idea was to make a collection, much as other kids collected stamps or coins or both. It was all part of an era when tigers were still fair game. Fortunately, I think all the southern tigers had been driven out already, or we might have had the tables turned on us. However, there was plenty of wild boar running freely. Today, I think both ventures deplorable, but then I don’t live in an unprotected hut.

In retrospect, it shows just how easily youth is sucked into handing out death for little or no valid reason; we should not be surprised that wars continue apace.

Rob