This Woman Seems Like a Nice Person, or at Least She Looks Like One

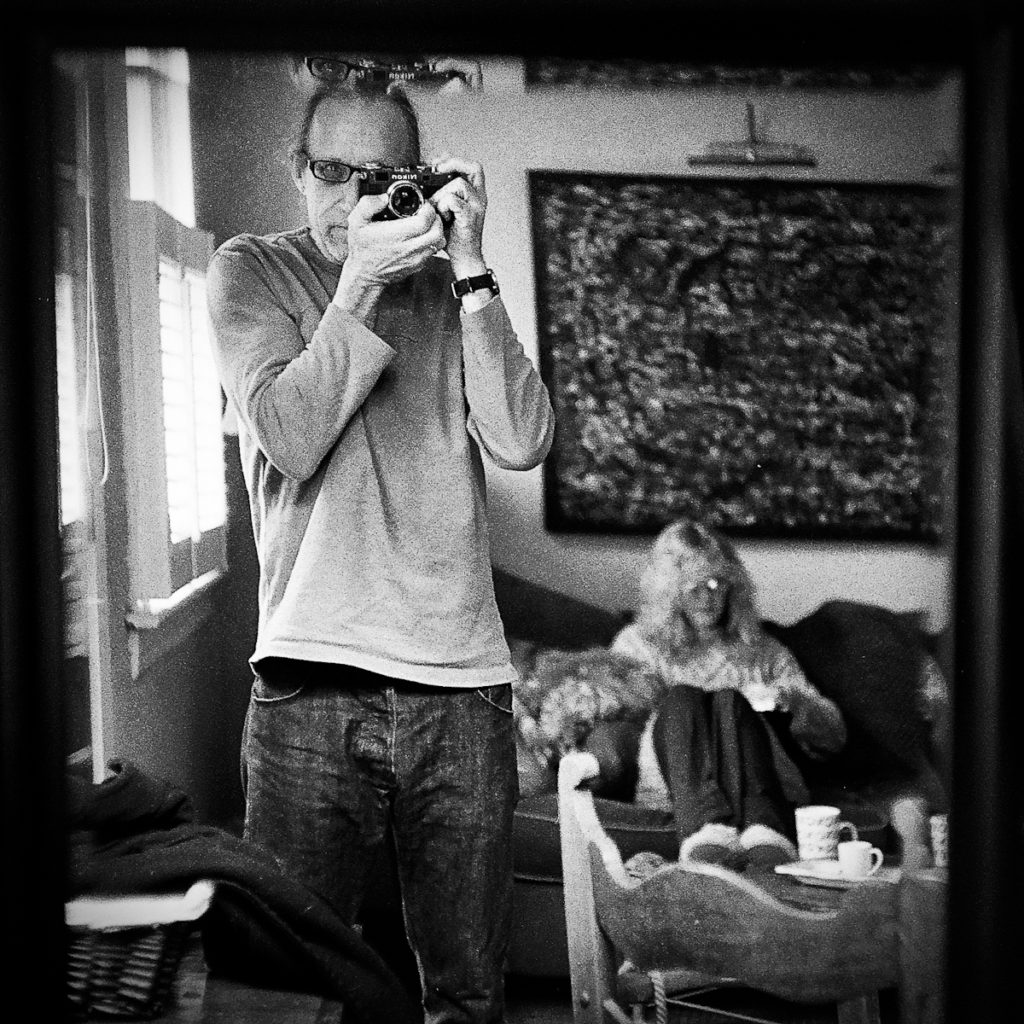

“Photographs furnish evidence,” wrote Susan Sontag in On Photography. “A photograph passes for incontrovertible proof that a given thing happened.” Sontag went on to admit that photographs might sometimes misrepresent situations, but the basic premise went unchallenged: Photos show us things that exist. It’s because of what we perceive as the photo’s truthful reliability, the “indexicality” issue we’ve beaten to death in the last post and accompanying comments. That’s a photo of me, over there; Sontag would say it’s evidence I exist. (I do.)

“Photographs furnish evidence,” wrote Susan Sontag in On Photography. “A photograph passes for incontrovertible proof that a given thing happened.” Sontag went on to admit that photographs might sometimes misrepresent situations, but the basic premise went unchallenged: Photos show us things that exist. It’s because of what we perceive as the photo’s truthful reliability, the “indexicality” issue we’ve beaten to death in the last post and accompanying comments. That’s a photo of me, over there; Sontag would say it’s evidence I exist. (I do.)

Of course, Sontag wrote in 1977, before digital photography was a thing. Now, go to the website “This Person Does Not Exist”. There you’ll see nice, unmanipulated photos of different men and women, normal looking people you’d expect to meet during your day, people just like me up there – except that the photos aren’t of real people. The people in the photos do not exist and never have existed (one of these non-existent persons is shown in the photo heading this post). Their existence has been generated via an algorithm, in this case, a “generative adversarial network” which produces original digital data [read: a new photo] from existing sets of digital data [read: 1’s and 0’s created by a digital camera]. The generative algorithm scans photos of real faces and creates new photos of new faces from them. Voila! A real photo of a fake person.

Now, take a look at that photo. If I hadn’t told you the above, if I were to tell you that was my wife, or a friend, or a family member, and that’s what she looked like, you’d believe me. All you readers arguing with me in the comments section about indexicality, you’d believe me because photos, film or digital, basically tell the truth, right? OK, it’s digital, so maybe it might have been photoshopped a bit, a few pimples removed, eyes brightened, a few crow’s feet smoothed over…but the person is real, they stood in front of someone with a digital camera, obviously they exist, and they probably look something like that. Right. You guys crack me up, unable as you are to see past the outdated conceptual blinders you wear. For those of you arguing against the idea that there really isn’t much difference between the presumed truthfulness of film versus digital photos, go to the website and look around.

*************

in 1945, film critic André Bazin (1918-58) wrote an essay entitled ‘The Ontology of the Photographic Image’. ‘Ontology’ is a word you’ll see a lot in philosophy. It’s the study of the ultimate “being” of a thing (e.g. “What do we mean when we say a thing is an animal?”). To discuss the ontological status of photography is to consider what particular kind of thing a photograph is. Kazin’s interest in the ontology of photography leads to Susan Sontag (On Photography, 1977) and Roland Barthes (Camera Lucida, 1980).

I’ve already discussed Barthes at length elsewhere. In Camera Lucida, Barthes employed a philosophical method associated with Jean-Paul Sartre called “phenomenology”, Barthes himself noting the book was written “in homage to L’Imaginaire by Jean-Paul Sartre.” Sartre wrote L’Imaginaire in 1940, a few years before Kazin’s essay, wherein he applied the ideas of Edmund Husserl, the founder of phenomenology, to investigate various kinds of images, including photographs.

Sartre’s point in L’Imaginaire is that there are different kinds of apprehending, correlated with different kinds of objects. Sartre says that when looking at photos we must “intend pictorially”; i.e. apprehending something as a picture is different from apprehending something as a simple object. “If it is simply perceived, [the photo] appears to me as a paper rectangle of quality and, with shades and clear spots distributed in a certain way. If I perceive that photograph as ‘photo of a man standing on steps’, the neutral phenomenon is necessarily already of a different structure: a different intention animates it.” That’s classic phenomenology, where every conscious experience has “intentionality,” which is a fancy way of saying that everything we think is shaped by the category we place the thing thought about.

Barthes, following Sartre, notes the difference involved in perceiving a photo versus perceiving it as a photo. For Barthes the essence of perceiving something as a photograph is ‘that-has-been’: “In photography,” he writes, “I can never deny that the thing has been there”. The person in the photo exists, Barthes is saying; the photo is the proof. By contrast, no painted portrait can compel me to believe its subject had really existed. Hence “This-has-been; for anyone who holds a photograph in his hand, here is a fundamental belief… nothing can undo unless you prove to me that the image is not a photograph.”

So, what of the analyses of Bazin, Sartre, Sontag, and Barthes in the digital age? I’ve discussed the implications of Barthes’ thought here. Listen again to what Barthes considered the ontology of photography: “This-has-been; for anyone who holds a photograph in his hand, here is a fundamental belief… nothing can unless you prove to me that the image is not a photograph.” Using this definition, a digital photograph is not a photograph in Barthes’ sense of the word. This is true of all digital photos, and not just the real images of fake people on “This Person Does Not Exist,” because the necessary connection to the real thing photographed has been severed and replaced by its connection with a string of 0s and 1s stored in a computer file. With the onset of the digital age, in the words of William Mitchell, there is now “an ineradicable fragility of our ontological distinctions between the imaginary and the real.”

*************

Jean Baudrillard, Enjoying a Gitanes While Thinking Deeply

So, if digital images are not photographs in the traditional sense, what is their ontological status – what kind of thing are they? According to Jean Baudrillard (1929 – 2007), French philosopher, cultural theorist, political commentator… and photographer, digital images are “simulacra.” Baudrillard was a Semiotics guy like Barthes, who wrote about diverse subjects, including consumerism, gender relations, economics, social history, art, Western foreign policy, and popular culture. He is best known, however, for his thinking about signs and signifiers and their impact on social life, in so doing popularizing the concepts of simulation and hyperreality. And, luckily for us, he was minimally aware enough of his surroundings not to get run over by a truck, like Barthes, and so lived to see the digital age.

Baudrillard’s post-digital world is made up of surfaces populated with self-proliferating “simulacra”, which are not copies of the real but their own thing, the hyperreal. Where classic philosophy saw two types of representation— 1) faithful and 2) intentionally distorted (simulacrum)—Baudrillard sees four: (1) basic reflection of reality; (2) perversion of reality; (3) pretense of reality (where there is no model); and (4) simulacrum, which “bears no relation to any reality whatsoever.” Digital photos are in the 4th category – simulacra – and are generated “by models of a real without origin or reality: a hyperreal. The territory no longer precedes the map… it is the map that precedes the territory. It is … whose vestiges persist here and there in the deserts that are… ours. The desert of the real itself.”

The problem with our new digital world, as Baudrillard sees it, is that our sense of reality is in the process of being inexorably altered by the endless profusion of non-reality based images, “simulacra.” In phenomenological terms, the categories we assign things to have been altered; that is to say, digitization has altered our ontology. As Sartre noted, from a phenomenological perspective, photographs form a distinctive category of objects. To see a picture as a photograph is to put it in a category. Now, for Baudrillard, to see something as a digital image is to locate it within the category of simulacra, the not-real, if only subconsciously (Baudrillard would say that we will gradually transition consciously once we’ve realized the ruse is up). This is the radical opposite of Sontag’s claim for analog photography. For Baudrillard, with digital’s severing of indexicality, we can never be certain what kind of image we are seeing, and so, by default, we must assign it to the category of simulacrum. Where once the image world provided us with windows onto reality, the image world now surrounds us in fictitious landscapes that heighten ontological uncertainty by eradicating the distinction between real and not real.

*************

Do the programs that produce these images of unreal people or unreal objects include in their datasets, data from digital images of real people or real objects?

It has never been quite as clear cut as the philosophers would like, but then, nothing is. Photo-realistic painting/drawing has been a thing for some time now, after all, and does not seem to be much different from the results of an AI. That is to say, the opportunity to mis-categorize photo-like objects has been with us for a while. The point has to be, therefore, simply that these opportunities are more numerous, and will fairly soon reach the point is being universal.

The notion that we, nowadays, categorize photographs we see online “differently” is certainly a notion that’s being floated. I’ve floated it. I’m not certain about that, though.

For the most part, the default assumption remains that the category of the thing we’re looking at is — functionally — an index. There may be some subconscious machinations that re-categorize it, or (possibly this is saying the same thing) you can say that people are simply more suspicious of the veracity of pictures.

It does seem inevitable that trust of “photographs” will vanish completely in a few years, but my best guess is actually that something we did not predict and cannot currently imagine will occur instead.

In part it depends on what happens with the digital photographs people make. If, as a category, they remain roughly as trustworthy as the analog photos of yore, then people will continue to trust them in roughly the same way, I speculate.

People will begin (have already begun?) to mentally subtract modifications: her eyes are probably not that big, her lips are not that full, and her skin is not that smooth.

Where do we land then? Is it then a simulacra that nonetheless provides a useful pointer back to the real world? We will, likely, still recognize the subject of the portrait, and there remains an element of “this-as-been” lying around here, most likely, but maybe not.

Good read but I am not sure that your example is pertinent for several reasons.

Your image generated by algorithms has nothing to do with photography or at least no relation with its etymology.

The fact that an image can be created by algorithms removes nothing from the real (if not true) character of digital photography. When your dentist gives you a dental X-ray, do you question his diagnosis on the grounds that it is based on a digital image? I hope not…

After Barthes, Baudrillard. I hope that neither Foucault, no Derrida nor Deleuze have written on the photography… Back to Baudrillard. I do not know where you saw that he made a link between digital photography and simulacrum. If there is simulacrum, it is in the use that one wants to give to the representation of the real much more than in its technical aspect. Nothing new here, it has always been part of photography (read Pierre Bourdieu – “Un art moyen, essai sur les usages sociaux de la photographie” – , it gives a good description of the use of photography as a tool of social conformity to class codes as well as contrived significant). The fact that the simulacrum becomes dominant today is primarily due to the predominance of the society of entertainment that requires a faithful medium to its objectives to maintain the majority in the consumerist illusion. As Guy Debord wrote decades ago in “La société du spectacle”, publicity has replaced reality and, I would add, it happened way before the digital age.

This guy totally agrees with you, Nic

“When your dentist gives you a dental X-ray, do you question his diagnosis on the grounds that it is based on a digital image? I hope not…” No, but I certainly could…and that’s Baudrillard’s point. We now can’t rely on the basic truthfulness of photography as a process; rather we need to rely on the person claiming the photo is true. My dentist? I assume he’s not messing with me. My real estate agent? Maybe, maybe not.

What is the purpose of portraiture?

The answer of course is to produce a likeness of the person who is featured in the portrait. For centuries, people have paid good money to have an artist make their likeness, something which has become somewhat cheaper over the years, particularly with the advent of the Kodak Box Brownie.

There have always been people, often French (or living under French influence), who have set out to confuse the issue. There have also been those who have set out to be as accurate in their art as is possible, Vermeer being a good example.

However the fact remains that the purpose of portraiture is for an artist to produce a likeness of his client, one that will satisfy.

Oliver Cromwell wanted to be perceived as a commoner when he insisted that when he was painted whilst head of the English Commonwealth that the artist ensured that his imperfections were reflected in his official portrait… “warts and all”. Robert Plant hates to be photographed from a particular angle, and gets angry if someone depicts the side that he doesn’t want seen. Pádraic Pearse would only be photographed from the right side, since he had a pronounced squint in his left eye.

Either way, the client might well refuse to pay, if the result is something he doesn’t want, so the artist who produces a picture of someone who doesn’t even exist, will be a poor artist and the person who creates the program that made that happen will not sell many copies of his program.

Of course there is a counter to this: I am not sure how popular it is now, but a couple of years back my kids thought it was great fun to snap me and then turn me into a dog, or a monkey or something, there were/are apps made specifically for this purpose. They were all the rage at the time.

I suppose there is less freedom with the silver nitrate system than there is with either pigment or 1’s and 0’s, but the latter is definitely more convenient, especially if you are being paid to produce a portrait.

If you aren’t, you might want to remove a crows foot, or stick some puppy ears on, but as I said in the last piece, that is just part of the fun.

In the end, one’s choice of medium is just that.

I am picking nits, but M Baudrillard is enjoying a Gitane, unless the other one he was smoking has been digitally removed.

“This-has-(maybe)-been”

Is that phone call, email or text message from a human or a robot? Is that visage on the screen of an actual person or a simulacrum? Is that Facebook pal a true friend or an algorithm? Is that news story imaginary or factual? By now, audio-visual simulation and manipulation is so easy and effective that fake is the new normal. It would take an impossible amount of time and effort to verify reality in all the media inputs we receive every day, so we must choose between accepting most of it at face value or doubting just about everything. Naturally, acceptance is the easier choice.

A tiny aesthetic community still exists that values things like optical images projected on photographic emulsions or sound waves engraved in phonographic grooves, but it’s on the wane. The creative limitations of chemical and mechanical media are so many and those of electronic media so few that the choice in the cultural marketplace was made many decades ago. Real life is bounded and boring while virtual life is boundless and exciting. Why stay here on terra firma when we can so easily go to the infinite and beyond?

I see you wore shades for your latest photo. Gotta be careful now, someone might steal your face. Did the Grateful Dead not have the future figured out a long time ago or what?

As mentioned before, I don’t subscribe to the idea that photographers, as distinct from lawyers or prosecutors, really have a spiritual difficulty in accepting either film or digital original exposures. They are just different ways of getting to the same end point: an image. We can quibble about the way each treats highlights, shadows and so on, but if our pictures look good when we save them…

Of course, this ignores all the ramifications of possible fraud or misrepresentation of whatever has been photographed, which is what your Barthes Peroid postings have been about. This was always possible, especially in press situations where words accompany images. That digital manipulation creates a far greater opportunity for that cannot be denied. But does that, of itself, create more distrust of images today? I’m not convinced. Since the advent of Trump, everything has been corrupted with regard to received information thanks to the popularity of that phrase, fake news. We just doubt pretty much everything that comes over as official stance, even if the grain is from genuine Tri X straight out of the cassette.

Does it matter, outwith politics etc. or are some of us just adopting some imaginary moral high ground for reasons not quite clear? Since giving up printing, I find that I enjoy looking at photographs just as much on a screen. In fact, and I really have no idea why, despite having a calibrated monitor, my images always give me most satisfaction viewed on an iPad; maybe the look on those screens is as close to glazed WSG as one can get? And that was my standard.

I have dozens of expensive, nice prints in their archival sleeves in boxes I no longer open; I wonder if I am alone there, am missing something or have just accepted that the times they have changed, like it or not? My website gives me a very convenient place to store my pix for instant viewing for whatever purpose; it doesn’t matter if anyone else sees it or not: the convenience is mine.

In order to make available access to correspondents’ pix, as mentioned in reply to your question about contributions from the readership, why don’t those of us with websites make them available as a matter of course?

http://www.roma57.com

Rob