It is always good to keep your eyes wide open, because you never know what you will discover. The drive to live life more alertly being an instinctive need, whether you are an artist by trade or desire, the art of seeing well is a necessary skill, which fortunately can be learned. -Michael Kimmelman

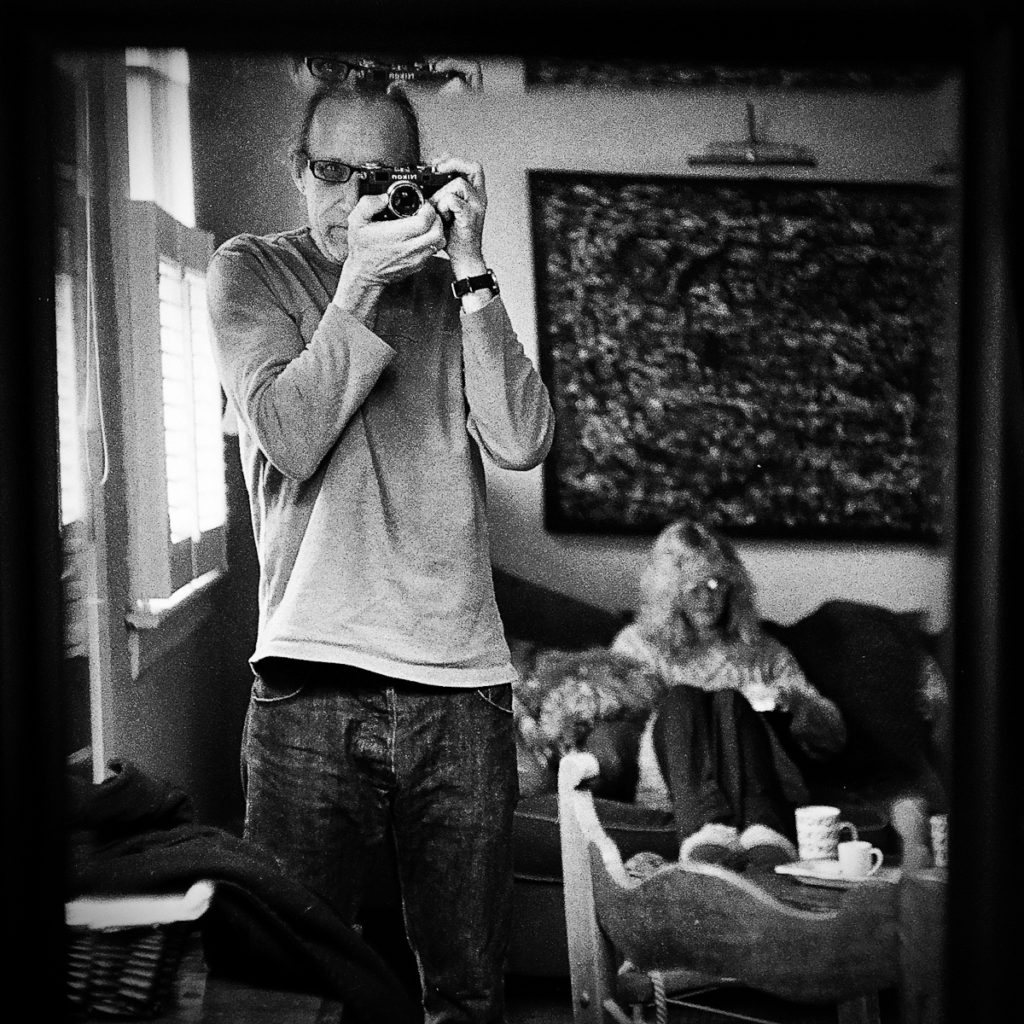

What’s the point of photography? Maybe the bigger question is: what’s the point of looking at things, really looking at them? That’s what we’re doing when we photograph. Granted, we’re placing a value on preserving how something looks, whether it be a lover, a pet, a glimpse of what we daily encounter…. but we’re also attending to it in the moment. That’s why we value simple photographic tools – mechanical rangefinders the perfect example – that get out of our way and allow us to experience the moment without having to ‘interface’ with a machine and its requirements.

A good example is the difference between using my M5 or my Ricoh GXR with the M module. I rarely even use the meter in my M5; I find it more a disturbance than a help. What I like is the big, clear 35mm window, no clutter, just a focusing patch and you’re done dealing with the machine. Look at the light, set your exposure and forget the little details. The rest is looking. The Ricoh? Great little camera, but I’m constantly fiddling with something – a menu, an ISO setting, something flashing on the damn LCD – my attention drawn away from what I’m trying to see. It’s the story of every digital camera I’ve ever used; once you reach a certain level of competency i.e. you’ve distilled the photographic act down to its basics, all those technological ‘aids’ – those things camera makers promised us would make our experience better – just get in your way.

*************

For that matter, what’s the value of what we as photographers create? What’s the value of looking at a photo hung in a gallery or museum or published in a book? Why is it so important to us? For me, the point is the process of perceiving itself. It meets some primal need humans possess. But it also has to be disinterested to be an aesthetic experience. Looking at porn isn’t aesthetic, no matter how well done; the reason it isn’t is because we’re motivated by something other than the enjoyment of beauty. A genuinely aesthetic experience of beauty is aimless. We only fully apprehend the experience when we remain disinterested. A vested interest in what you’re looking at gives you tunnel vision. You see what you’re looking for, and as such, you don’t really see.

Photography allows me to move through the world with an attitude of detachment, in a state of heightened awareness. I’m always looking…which means I’m seeing things people habituated to their environments typically don’t. That’s pretty cool; we’re not here long. Best to pay attention while we are.

Photography – or, more precisely, film photography, where there’s typically a lag between what we see and how we see it reproduced by the camera – amplifies the enjoyment I get in looking. It allows me a second chance to see something I’ve already seen and to see it with new eyes. It’s why I find myself increasingly drawn to photograph the people I love. I’ll run a roll of HP5 through my camera in a day or two, just shooting domestic scenes around me – my wife, the kids, my dogs – and throw it in the pile of rolls to be developed at some later time. That invariable means a year or two down the road, when I’ve accumulated enough unexposed film to shame myself into doing something about it. When I develop them I’m always amazed at what I get. The banal circumstances of my domestic experience seem somehow re-valued and take on a larger meaning. The photo puts them in context. I understand what I see – and value it – just a bit better.

*************

Howard Axelrod, in The Stars in Our Pockets, addresses the technological processes that remove us from having to pay attention. GPS is an instructive example: with it we passively navigate our environment without reference to its larger context or where within that context we fit. It’s all end result – do we get there, or don’t we. (He doesn’t address the larger issue – that we’re also using a machine to move through space which itself mitigates our environmental interaction). Axelrod asks, “Will we still be able to achieve a kind of orientation that is really a kind of wisdom?”

It’s this “orientation that is really a kind of wisdom” that photographic looking gives. The heightened attention it cultivates can be difficult to practice. Really looking with disinterest requires effort. You can’t do it if your attempts to do so are mediated by tools that divert your attention instead of focusing it. In a photographic context it requires the correct tool, something that remains transparent to our purposes. This is why we hold onto those cameras that become extensions of our seeing through excellent haptics and long usage. Usually I don’t even recall putting the M5 to my eye; it’s such a simple act, done so many times, that its reflexive now. The digital camera? Not a chance. Even though it’s full of the technologies that supposedly simplify my experience – auto exposure, autofocus, auto ISO, facial recognition, etc etc, they’re never transparent to the act; I’m always scrolling through some fucking menu, or looking for some dial to turn or button to push in response to some LCD readout. The camera is telling me what to see.

There’s a reason we love our old mechanical film cameras. When used competently and correctly, they allow us to give ourselves over to the moment. We can exist in the moment for no reason or purpose other than that of the experience alone, for the appreciation and apprehension of what’s in front of us. That’s a remarkable gift. It’s also what’s required if one wants to produce work of any meaning, work that will help others see as well.

Views: 28

Great job, Tim! Another brand new angle (at least for me) to tackle the issue between film and digital photography. Anyway, thank you and congratulations!

Regards,

Jinw

By having to wait a while (not seconds or minutes as you would with a digital camera) between taking the picture and seeing a contact or print, you allow yourself to forget some of the subjective aspects of the photo and can better judge it as an image in its own right. I sometimes go back to proof sheets and work prints a year or more later and discover images that I missed or just looked at differently earlier on.

Pieter, as with Saul Leiter, I’m in no great hurry.

The only time I process a file quickly is when I’m at home and have an idea for a shot and find the drive in my head actually to do it; then, yes, I do put it into the computer straightaway. At such times I thank God for digital because it’s cheap in cash terms, and gives me the chance to do it again at once if I am not pleased with what I shot. For outdoors stuff, I have no idea at the moment what is or is not on my card or even if there is anything there at all. As it’s all a matter of supreme indifference to me now, and nothing but a diversion, something with which to fill the long hours, it’s actually a safer bet because as far as I can tell, unlike film, files don’t suffer from any loss of latent image if you take a long time between exposure and processing.

That’s something that worries me about Tim’s technique of saving films for months before processing them. It might be interesting to shoot the same thing on two rolls, process one immediately, and dump the other in the “next year” bag. Given that the same camera and setting is used, would the difference be visible? Without a densitometer, perhaps not unless one had been using transparency film.

Sometimes, not knowing something can make you a happier person. I often think that of death, but on the other hand, if one knew the date of it, then it would be possible to make an informed choice about how much to spend, whether or not to start on the G&Ts again or to bother having the car serviced. My diet would also change quite a lot. No, I wouldn’t start back on Lucky Strike (LSMFT!) or Chesterfield. I remember my mother bringing me back from Switzerland a few packs of Turmac ciggies when I was young. Never, ever found them in Britain. This was probably in the late 50s. I remember them as oval in cross-section, and not because of a crushed pack, which all these years later I remember as blue. Though it might easily not have been. The very thought of smoking is enough to give me the sensation of a sore throat, which is exactly what has happened to me right now. So much for the powers of autosuggestion; that’s one more reason why one must be careful for what one wishes.

🙂

Thanks Tim,

Regarding this: “Photography – or, more precisely, film photography, where there’s typically a lag between what we see and how we see it reproduced by the camera – amplifies the enjoyment I get in looking.”

This might well be another good reason for using film, for when we are photographing subjects (or objects) that are familiar, are we not actually taking a look at ourselves? Some kind of visual aide memoir? Perhaps by the enforced gap between the creative thought and the eventual revelation, might we not be revealing more about our “then state of mind”?

As I believe Kurt Vonnegut once wrote: “Enjoy the little things in life – because one day you’ll look back and realise they were the big things.”

I was accustomed to having “the family” around for Sunday lunch for many years. One such day, my mum and dad were complaining about mobile phones, this was before phones were “smart”. They had these dinky little devices that were only switched on when they wanted to make a call, otherwise the battery ran down (or something).

I pointed out that if they became separated, say when out walking or shopping, they would not be able to contact each other, so what was the point of having one in the first place? That went nowhere…

Then my son pointed out that they also had a camera, and you could make little snapshots, without carrying the “sureshot”. So my mum handed him the phone and said, show me, take my picture. So he did.

That was the last time they came for Sunday lunch, she died on the following Thursday. I carry that picture around in my wallet, it’s crap, but it is the only one there is.

As I believe Kurt Vonnegut once wrote: “Enjoy the little things in life – because one day you’ll look back and realise they were the big things.”

So true.

“I pointed out that if they became separated, say when out walking or shopping, they would not be able to contact each other, so what was the point of having one in the first place? That went nowhere…”

I know their feeling: my wife and I both had the old cellphones too, and they were always off unless WE wanted to make a call. Perhaps your folks were the same as us: we were always together. There was a snowball’s chance of us getting seperated or lost from one another, and in a little town like ours, we couldn’t avoid finding each other again just by going for a coffee at the regular bar. Life, as you no longer have to go out to work, changes completely. That aside, I have always thought of the cellphone as yet another intrusion, unless you use it very carefully, and for me, that means as an emergency measure.

And for those still working for a company, it is even worse: no respite and being at your employer’s whim, even when taking a shit.

For the working freelance: a godsend. But that’s professonal life, where you want all the connectivity with a possible client that you can get: it can mean work for you.

Basically, much of today’s fantastic means of communcation are about the transmission of trivia. And a wonderful way to avoid meaningful contact. Send a few e-mails or texts, and you can do without actually having to go and see people for ages! What’s not to like?

“1. This might well be another good reason for using film, for when we are photographing subjects (or objects) that are familiar, are we not actually taking a look at ourselves? Some kind of visual aide memoir? 2. Perhaps by the enforced gap between the creative thought and the eventual revelation, might we not be revealing more about our “then state of mind”?”

1. We are certainly looking at something that resonates. otherwise we wouldn’t be shooting it.

2. Our then state of mind is fleeting, and if we are doing as per (i), then we are on autopilot already and our “then” is no deeper than our image. What are you really expecting to discover during this hiatus between click and finished pic?

When I used to go away on long calendar shoots I was invariably using colour trasparency films. If it was on 135 format I’d go to Hemel Hempstead on return, and get the Kodachrome overnight rapid turnaround service they provided for pros – at additional cost. If larger format was needed, I’d have to use Ektachrome and that I got processed locally in Scotland. Either way, the time between the start of the gig and the editing process on my lightbox meant that by the time I had the Schneider Lupe 4x in hand, much of what I was looking at was kinda new to me, and often the great shots (in my head) were not so great, but something else that had gone unremarked at the time turned out surprisingly well. Of course, I sometimes got it right in the emotional moment, and what I thought great actually was. But none of this reveals anything about my mind processes in the moment, just about how much I was or was not being deceived by the mood during the shoot. If there’s to be a critical analysis of self to be discovered, perhaps it lies in how much we are aware of being constantly deceived. And if deceived is too harsh a word, maybe it might reveal how much we fail actually to understand our surroundings and their implications; our human failure to grasp the broader picture, as it were, and disassociate it from what we want things to be.

What’s the point of photography, Tim asked.

Good question, and perhaps it’s that in the sense of amateur photography it boils down to two main things: it lets us record memory, however imperfectly and how dangerously, and it allows us to express some developed or nascent artistic urge. Professionally, if you can pull it off, it provides a living which – if you get really lucky – also permits you to indulge your fantasies beyond what you could on your own dime. Money aside, if it’s a gig, that magically authorises and legitimises whatever you had in mind. It gives better Dutch courage than booze.

It can also become a crutch, a substitute for a real life. Could it be a hallucinogen?

I find it difficult to subscribe to the notion that something has to be “disinterested” to have aesthetic value or merit, and neither does it strike me as likely that looking at a photograph that interests one implies having tunnel vision. Surely, it’s the skill of the photographer that drives one to whatever one sees or fails to see in the image in the first place? Very often I don’t actually think that I see anything specific at all: I just derive mood and satisfaction from that. It’s why true abstracts can be fascinatingly attractive. Chickens, eggs?

Concerning living in the moment: for me, that happens when I put on a really long lens. I may have mentioned this here before, but the act of focussing my 500 Nikkor reflex gives me a greater buzz than the actual pictures derived from it: the difficulty of, and clear changes brought about in the act of focussing are tangible, almost edible, especially if you have some foreground stuff going on: that sense then is almost of 3D! You lose all of that dynamic in a single frame. And that’s also where motion scores heavily over stills, even in landscape – or perhaps even more so in landscape: you get more of the sense of place by scanning than by having to settle for picking the cherry. Often, there is no absolute cherry.

I may be midunderstanding both you and Axelrod, but surely, you have both put that horse in front of the cart? Isn’t it what’s in you that motivates the looking and seeing in the first place, and hardly the other way around, that by being disinterested you can see?

I agree about equipment complexities getting in the way, but not that digital cameras are more likely to distract one: it all depnds how you set them up, and some modern things in digital remove the need for manual adjustments that my film cameras did.

Perhaps you have a point when you mention the viewfinders on rangefinder bodies, but for anyone like me who enjoys shallow DOF, they are anything but helpful! Of course, if you really subscribe to f8 and be there, there’s no argument. Existing too much for the experience of the moment means one might never really require to load any film…

🙂