French Post-Modernist Intellectual Roland Barthes, Pondering the Studium/Punctum Distinction With the Aid of Non-filtered Gauloises

Consider this Part Two of my previous post on Barthes’ Camera Lucida. There, I gave what I considered the gist of Barthes’ thesis on Camera Lucida, the main point you as a photographer can take away from the book. My intent was to de-mythologize the book and make it intelligible to an educated lay readership. In my opinion, any thinker who can’t articulate his thought so that it’s understandable to an educated lay reader probably doesn’t have very coherent ideas to begin with.

Which is not to say Barthes didn’t have much to say. He did. He just suffers from the annoying tendency of “French Intellectuals” to make their thought sound more profound than it really is by expressing it in jargon that obscures it. This has had the unfortunate result that it’s also allowed less interesting thinkers than Barthes, or often thinkers with nothing to say, to join the debate simply via having mastered the appropriate in-group jargon (read this woman if you have questions). Much of modern Semiotics thought, of which Barthes is a pioneer, is, honestly, a mess of incoherent garbled nonsense.***

While I’m not denigrating Barthes’ thought, it’s instructive to compare Barthes’ Camera Lucida with Susan Sontag’s On Photography, written about the same time. Where Barthes is maddeningly opaque – he speaks of “the wound” of the punctum, the “Dearth-of-Image,” the “Totality of Image,” i.e. the usual jargonist clap-trap – Sontag, good practical, American intellectual she is, gets to her point clearly and concisely, absent in-group jargon, seemingly without the need legitimize her thought by unnecessarily obfuscating it.

*************

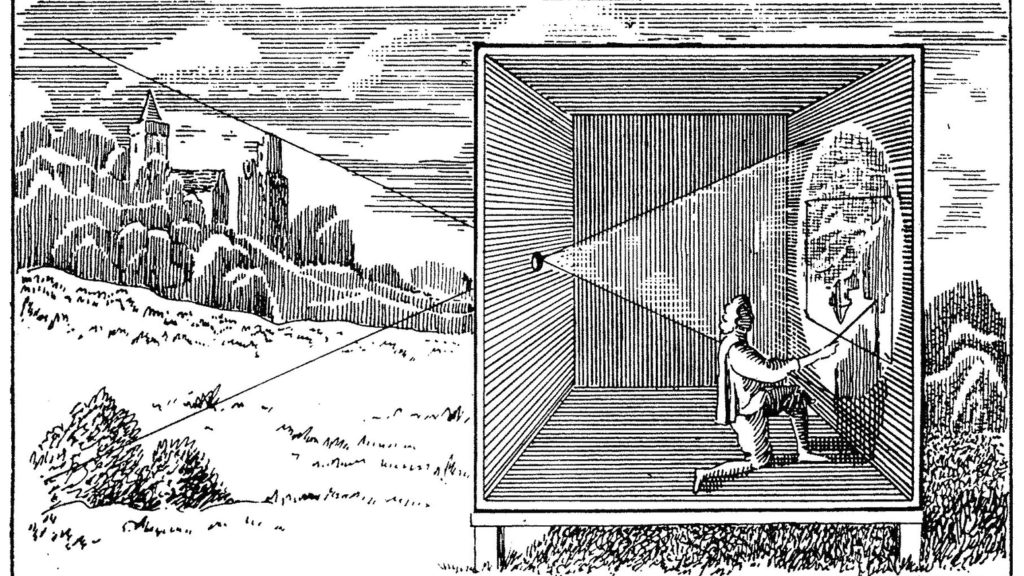

The Camera Obscura, Predecessor of the Photographic Camera

The question I posed at the end of Part One was this: What, if any, are the implications of Barthes’ ideas, as expressed in Camera Lucida, for ‘post-analog’ (i.e digital) photography? After posing the question, I then suggested the answer should be fairly obvious. As I see it, it’s this: Digital capture has severed the direct connection between the thing photographed and the resulting photo. “Photography” as commonly practiced today no longer possesses the one characteristic that made it unique among communicative media – its “Indexical,” as opposed to its “Iconic” relationship with what is real, what’s actually out there.** As such, you could argue it isn’t even “photography” anymore as the term is understood etymologically, but rather a new species of graphic arts. [Years ago, when I was naive enough to think that one could actually intelligently discuss issues like this on the net, I suggested this on a popular photography forum, whereupon forum “mentors” chortled at such  ridiculousness (one “mentor” – a retired insurance salesman who mentors readers on the intricacies of varoius camera bags – opined that only an idiot could think such ludicrous things), forum members pointed at me and laughed, moderators’ heads exploded, and shortly after I was summarily banned, for life, no possibility of reprieve, banished to the nether regions of web-based photographic discourse. My response? I started Leicaphilia.]

ridiculousness (one “mentor” – a retired insurance salesman who mentors readers on the intricacies of varoius camera bags – opined that only an idiot could think such ludicrous things), forum members pointed at me and laughed, moderators’ heads exploded, and shortly after I was summarily banned, for life, no possibility of reprieve, banished to the nether regions of web-based photographic discourse. My response? I started Leicaphilia.]

At the time Barthes wrote, when photography was the result of analog processes identical to those of the camera obscura (see above), we could rightfully assume that a photo necessarily dealt in the real and was more or less faithful evidence of the real. While someone could manipulate an analog photograph to a certain extent, the exception proved the basic rule: photography, in the words of Susan Sontag, was the stenciling off of the real. It was “evidence” of the real. For Barthes, that’s what makes photography absolutely unique as a medium of communication, Its very essence as a medium.

Digital capture doesn’t “stencil off” anything; rather, it turns everything into computer code which then needs to be reconstituted by more computer code. The “digital revolution” isn’t about simply providing more efficient photographic tools; rather, it’s a profound revolution of how we recreate the visual with similarly profound implications for its claim to being “true” by simply being. Unlike the photographic processes Barthes analyzed, digital processes de-materialize everything into non-material 1’s and 0’s ephemerally housed in computer “memory,” data that must then wait for an algorithm to reconstitute it “realistically” or transmogrify it into anything else imaginable, dependent upon the intentions of the algorithm’s creator. Need to make your selfie more sexually attractive, your landscape more picturesque? Need to remove an ex from a family portrait? There’s a “filter” (i.e. a certain computer algorithm designed to translate the latent data a certain way to acheive a certain pre-determined result) for that. Hell, those 1’s and 0’s that constitute the RAW file, or the DNG or the JPG, can just as easily be output as music if that’s your desire, the point being that the guarantee of indexicality that Barthes sees as exclusive to photography is a thing of the past. To quote Wim Wenders: “The digitized picture has broken the relationship between picture and reality once and for all. We are entering an era when no one will be able to say whether a picture is true or false. They are all becoming beautiful and extraordinary, and with each passing day, they belong increasingly to the world of advertising. Their beauty, like their truth, is slipping away from us. Soon they will really end up making us blind.”

The blind already exist. They’re the smug enthusiasts who think an interest in “photography” only means better cameras with greater resolution, easier capture and hassle-free output, who would dismiss those like Wenders who recognize something more profound at play while they simultaneously embrace – no, celebrate – the technologies undermining and ultimately destroying photography itself.

**Indexical Signs = signs where the signifier is caused by the signified, e.g., light enters a camera lens, is focused on a silver halide substance, and produces a negative via a photochemical process. Iconic signs = signs where the signifier resembles but is not directly caused by the signified, e.g., a digital “photo”, wherein the “photo” has no direct causation by the signified and thus can only be said to “resemble” the signified.

*** For an example of what passes for intelligent discourse in Semiotics, this from the Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, literally opened at random :

The phenotext is constantly split up and divided, and is irreducible to the semiotic process that works through the genotext. The phenotext is a structure (which can be generated, in generative grammar’s sense); it obeys rules of communication and presupposes a subject of enunciation and an addressee. The genotext, on the other hand, is a process; it moves through zones that have relative and transistory borders and constitutes a path that is not restricted to the two poles of univocal information between two full-fledged subjects.

To create your very own post-modernist essay, go here and click on the generator at the top of the page.

I am not sure about this…

One could say that digitisation might well lead to the end of photography as we know it, since no longer will there be a bunch of chemicals involved in sticking some silver to paper. Oh no, with digitisation the final image has undergone some relatively simple re-interpretation. I say simple since even though it is a mighty stack of do loops, compared with what goes on in the human brain, it is very straightforward.

Interestingly, your preceding article Tim, was an evaluation of a digital scanner, which I have always thought an odd concept, even though I use one nearly all the time. The same applies to some of the alternative printing methods, where enlargers do not work, where actual contact needs to be involved, thus requiring the construction (through use of software) of a digital negative.

The problem with digitisation is that it is still very much in its infancy, we have crude translation systems, largely based around the ascii standards, and these have the effect of imposing limits on dynamic range, there are tabulated ceilings and floors.

However the actual method by which the input information is acquired is the same, whether you be Vermeer with a sophisticated camera obscura and a tray of oily pigment, Don McCullin, fixing that same image in silver, with a touch of the old dodging, burning and tinting by way of human intervention, or an iPhonographer who relies on AR (the hive mind) to arrive at a conclusion.

I s’pose what I am suggesting is that the only problem with digital is that it is currently at the stone age in terms of its development, indeed within those binary/ascii limits it might even be more faithful than the Vermeer/McCullin methods, both of which are very individualistic and depend on the mind and intellect of the artist.

I guess the best thing, especially where “events” are involved, is not to really believe ANY image other than what you see in front of your own eyes. All recordings whether written, sung or read, are open to someone else’s interpretation.

As Picasso said when being shown a photograph of an interviewer’s partner…

“Small, isn’t she”.

OK, digital not the real thing because of algorithm bla bla bla. But is analog photography with its inherent chemical bias that different? If silver grains are real (no doubt), aren’t they selective by nature?

Not sure Roland Barthes writings on photography are the best thing he did. I much prefer his concept of bathmology which is IMO much more innovative.

I won’t comment on Gauloises, I quitted smoking decades ago, only to say they taste and smell pretty bad (OK, Gitanes are worse…).

Last comment: Agreed, Susan Sontag is way easier to read.

“OK, digital not the real thing because of algorithm bla bla bla. But is analog photography with its inherent chemical bias that different? If silver grains are real (no doubt), aren’t they selective by nature?”

No. They are not “selective” in the sense they are the result of a CONSISTENT, UNIFORM chemical process and as such have an “indexical” repeatable relationship to the thing photographed.

Digital, meanwhile has no underlying consistent process that guarantees uniform, predictable output. It’s all up to the software you use to reconstitute it.

Well, consistency of the process is not a guarantee of truth. Can you swear that reality has the discontinued aspect one can notice when looking at a negative through a magnifier? Is reality black and white or, for those shooting color film, has different color layers? When a film cannot catch a scene because of a lack of light, does it mean that reality does not exist? Why using different developers if silver is not selective? I would understand your argument if exposing a film was enough to get an image but it is not the case. After exposure, there is a chemical process use to, as the same time, create a real image and distord reality. A such, the whole analog process could be compared to an algorithm (process to solve a problem, having a negative in this case).

I’m not going to argue the point further. You’re wrong if the point you’re trying to make is that there is no fundamental difference in terms of indexicality between analogue capture via a consistent chemical process and a de-materialized digitization into computer code that must be reconfigured with other computer code written by people. If you can’t see that I’ve got nothing further to say other than we disagree…and you’re wrong….and you should look up the word “index” to further understand where you’re wrong.

Merriam-Webster’s definition of “index”

I’ve gone back into the post and added the following as clarification:

Indexical Signs: signs where the signifier is caused by the signified, e.g., light enters a camera lens, is focused on a silver halide substance, and produces a negative via a photochemical process.

VERSUS Iconic signs: signs where the signifier resembles but is not directly caused by the signified, e.g., a digital “photo”, wherein the “photo” has no direct causation by the signified and thus can only be said to “resemble” the signified.

See JR’s comment above for an excellent summary of the differences.

Merriam-Webster’s definition of “indexical”

Film is chemical or chemicophysical. Digital is electrophysical or electronic. Both are indexical. Both are caused by the action of light on a substrate, photographic emulsion or photographic electronic sensor. The problem is that the recording of the electronic sensor, an electronic record itself, is much more easily and arbitrarily altered than is the chemical record of the film emulsion.

Yes, I think we have to disagree on that. IMO, being analog or digital, there is still indexicality (how could it be different?). Even a digital image is not coming from nowhere.

Re Merlin Marquardt:

Film photography requires only impersonal chemical processes, no human required i.e. in theory the process could be completely mechanized with no human interpretation. Digital photography requires a human interpretation – a subjective intervention – of a prior dematerialized electronic process.

All of these processes, film and digital, require human interpretation. Film is “subjective”. Film is designed and processed by humans and can be subjectively altered. Seems similar to digital to me. It’s just less versatile or alterable.

I think there is the potential to break the indexicality in chemical development, but that potential is severely limited, and the point is that the indexicality is inherent in the process itself.

With digital the index is not inherent in the process itself, it only SEEMS to be because we have created the algorithms to mimic chemical processing. Breaking the indexicality is a severe feature of digital.

Digital’s awful disruption (seen on the veneer as progress and falsely customer-centric) applies not just to photography but almost every other field. AI and the algorithms ability to mimic a photographer is here, as it is in music, customer service advisers etc.

JR’s two-penneth

I think of the digital as rendering the index more optional, and perhaps more metaphorical. You can render your raw file as music, but you normally choose to render it as a picture.

The index was always a bit of a metaphor anyways. Light flies off of Roland’s mother and smashes into some silver halide and then… there are some steps… and then light hits Roland’s retina!

The magical steps in digital photography are distinctly more fraught and less reliable than the steps of silver photography. But I think the index, wounded perhaps by one of Roland’s damned puncta, survives after a fashion.

First, on Gauloises, it’s a crying shame you can no longer get them in the U.S.

Next, yes silver compounds “interpret” light to create an image and need to be “interpreted” by the developer to render that image, so in that respect there is a parallel to today’s digital process. However, the 0s and 1s of the digital “image” make it easy to modify that image, often with little evidence that there has been a change. Witness new smartphone cameras that allow you to change the apparent depth of focus in an image, something that was once only possible when the photo was originally shot.

I disagree with you. The film capture is the result of a CONSISTENT, UNIFORM chemical process and as such has an “indexical” repeatable relationship to the thing photographed.

Digital, meanwhile has no underlying consistent process that guarantees uniform, predictable output. It’s all up to the software you use to reconstitute it.

Well, yes, but ultimately what we consider as reality or an accurate representation of reality corresponds to what we perceive with our “retina” or “visual system”, our nervous system. What appears on our retina or on the wall of the camera obscura or any analog projection screen, not to mention any digital screen, can always be manipulated or “distorted”. An easy example would seem to be the problem of color balancing or color matching in print for publication and analog photographic prints and digital media. It all seems a little arbitrary. The nature of reality can be relative and elusive and subjective.

I don’t think that the new method of image capture leads to any automatic, definitive statement that the king is dead. Really, the differences are not so much dependent on cameras or capture method but in what people choose to do with their file or electronic negative.

In a sense, a decent file coming from the sensor as flat and unworked as the camera is capable of offering it, might even be argued to be less interpretative than film/developer combinations. Carry this argument to colour films, and you can have yourself a verbal party to end all verbal parties.

If anything, truth is, as ever, in the heart of the photographer; if he wants to create fantasy, then yeah, today it’s pretty easy, but you still need to have a reasonably sound aesthetic sense or the end product just looks silly.

For a long time I was very much biased against digital, mainly because of the awful plastic look that seemed to be the way it defined skin. Today, that aspect doesn’t cross my bows much because neither do pretty women. In my current photography I find digital to be a far more useful tool: I don’t have to spend money on consumables because I have even stopped printing (not exactly by choice but by courtesy of HP and my dead printer). That said, there is nonetheless something that I find superior about my few remaining glossies on double-weight Kodak paper deloped in D163. That’s down to physical printing methods, not the fault or glory of the capture medium itself. Which is where I think we came in?

I may possibly be missing the point in this Part 2, but as I see it, that punctum and studium thing has lost none of its viability through the changes in capture methods: the photographic image still needs them as, indeed, does a painting. Photography was only ever a proof of truth in the mind of non-photographers.

Rob

Fake is the new normal. Truth is inconvenient…and generally unprofitable.

Hello. Just wanted to comment. I just ordered Barthes book, however whilst travelling from Paris to Champery to Rome before returning to London I have been reading Leicaphilia as if my life depended on it. Reading page after page, binge-reading like my kids do on Netflix, hooked on the connections to other photographers, other lives.

Recently discovered whilst searching for mundane “technical” reviews of Leica products, I am drawn inwards by Leicaphilia’s coverage of the important aspects of the photographic life. I don’t know why but I am reminded now and then of the writer Valery (The Method of Leonardo da Vinci) and Sebald (The Rings of Saturn). Get an editor and publish a small book please! 🙂

One point of difference, I do like bourbon, but my passion is for single malt scotch taken neat, never diluted, and as I read the wonderful writing on George Fevre and Artee James I am sipping a dram of Balblair 1983, loving the waves hitting my senses, yet sad knowing the bottle is now nearly empty, and no I am not listening on a bluetooth speaker, but a CD of Sandy Denny through my dads old Wharfdale E30s.

PS I would recommend Geoff Dyers “The Ongoing Moment”, a challenge to get through easily, but his focus on the still image and the men and women who fought hard to make something of it, I find inspiring. Anyway, just saying and please keep up the writing!

Best wishes

JR

Thank you, JR. Good to have you as a reader. Feel free to submit something for the site.

I think we can all accept that Ralph Gibson is a good photographer. At the attached URL he talks about how to negotiate the way through the tech and come out at the other end, still a good photographer.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ov5i-T4fOxE

If you have something to say, the recording method is not relevant. His old boss, Dorothea Lange intended to send the government a message, she didn’t concern herself over the developer, camera, printer that was employed. She took a run up, tried about five or six different scenarios and finally arrived at what we know as “Migrant Mother”. She set out with what she called “a point of departure”, and ran with it.

Me? I will never be a good photographer, it’s just a bit of fun and is an awful lot more absorbing than listening to an album, or watching a couple of teams of sweaty blokes fighting over a piece of wet leather.

I don’t really think that the digital method of recording is any different from working with light sensitive chemicals, or oily pigment.

The important bit is whether one is liberated enough (or childish enough) to be able to get it down on paper.

Where there might be an advantage to the older methods is all in the degree of co-operation required to arrive at the tools of the trade.

Where digital is hellishly complicated, superficially to make it easier for the artist, but in reality because it makes big bucks for the business man…

The paintbrush is really simple, so simple that folks can get an impression of the local wildlife down on a cave wall around 17000 years ago… that is even before Kodak.

Either way, if you ain’t got the mojo, you ain’t going to make a name for yourself.

Robert Frank took 28000 pictures and only 83 of them made it into arguably the most influential book of photographs ever published.

I am digging deeper into this tonight. However, this article is exactly the type of thinking that brings me back here again and again. I feel as if I could just roll the dice and let that result guide me to any page and there would be something amazing at that destination.

That is very kind of you, Chris. Feel free to submit something if you ever find a free moment. Tim

Thank you, I’ve been thinking quite a bit about Leica’s hardware from the point of view of user centric design, and I might take a stab at that. BTW, I grew up in Linden, NJ, did my undergrad at Montclair State, where I first studied photography. I saw the picture of you and your family in Wayne. I can’t say I know Wayne very well, but I had many friends from there in the 1970’s.