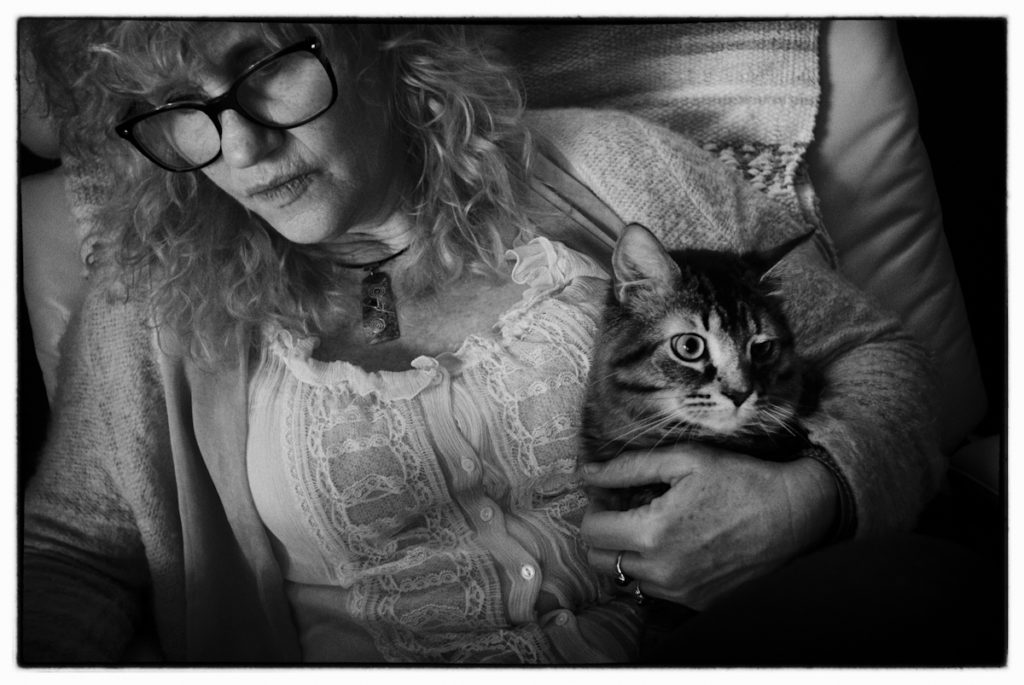

Wally Enjoying some Quality Time with the Wife – From a Fuji S5 Raw File

While I generally dislike almost everything about digital photography, one of the few things I’ve grown to love about it, as a matter of practical adaptation, is its versatility. (My dad would refer to this as “making chicken salad from chicken shit.”) You can start with a RAW file and create any variant of end result you prefer – color, B&W, sepia etc.

An old B&W film guy, I tend to remain one digitally, which means B&W output, which means, at the least, greyscaling RAW files. Unfortunately, simply greyscaling RAW files without more leaves you with what to me look like thin, plasticky photos that scream digital capture. Nothing wrong with that, I guess, if you like that look, but I think digital B&W looks like shit when compared to a good B&W negative wet-printed or scanned. It’s why the Leica MM Monchrom, a great idea in theory, never really interested me. You could argue that it instead of being a throwback to traditional B&W photography, it actually produces files that accentuate the worst aspects of digital B&W.

Enter “film emulation” software, which, surprisingly enough, attempts to take a digitally captured RAW file and create an end result that emulates the look you’d get were it to have been taken with a given film stock. Nik Silver Efex is the best example. Nik (now defunct) extensively researched the looks of various film stocks and produced algorithms that best mimicked the printed result of these films. Unlike what various self-appointed digital experts who give advice about the software seem to think, it isn’t simply a matter of applying an overlay of grain typical of a given film, but rather additionally, and much more importantly, replicating the characteristic exposure curve of a given film.

A Simple Greyscale. No Grain, No Film Exposure Curve Applied

What a lot of digital era photographers don’t seem to understand is that film captures light in a manner different from a digital sensor. A sensor doesn’t have an exposure curve; it captures light in a consistent linear fashion. Its “exposure curve,” if you could call it that, looks like a straight line ( see over there). What that means practically, is that, for example, if the light in one part of the photo is 4X the amount of light in another part of the photo, it will faithfully be recorded in such proportions by a sensor.

What a lot of digital era photographers don’t seem to understand is that film captures light in a manner different from a digital sensor. A sensor doesn’t have an exposure curve; it captures light in a consistent linear fashion. Its “exposure curve,” if you could call it that, looks like a straight line ( see over there). What that means practically, is that, for example, if the light in one part of the photo is 4X the amount of light in another part of the photo, it will faithfully be recorded in such proportions by a sensor.

Film meanwhile, doesn’t respond to light in this 1 to 1 fashion; rather, it does so idiosyncratically i.e. in its own individual way. This, much more so than simply the grain of a film, is what defines its specific character -what sets Tri-X apart (see to right) from HP5 for example. Typically, what happens with film is this: it’s less sensitive to low levels of light while being better able to reproduce highlights (as opposed to being “more sensitive” to highlights). Digital sensors tend to blow out highlights while film tends to compress highlight values and thus retain detail in strongly lit areas. The end result, generally speaking, is more nuance in the digital shadow detail and deeper blacks and more highlight detail with film.

This, much more so than simply the grain of a film, is what defines its specific character -what sets Tri-X apart (see to right) from HP5 for example. Typically, what happens with film is this: it’s less sensitive to low levels of light while being better able to reproduce highlights (as opposed to being “more sensitive” to highlights). Digital sensors tend to blow out highlights while film tends to compress highlight values and thus retain detail in strongly lit areas. The end result, generally speaking, is more nuance in the digital shadow detail and deeper blacks and more highlight detail with film.

And this is where emulation software runs into problems, because it’s necessarily working with a digital file to begin with, which means that it’s working with a file whose inherent highlights have already been compromised to some extent, and no amount of emulation can recreate highlight information that would be there on a film negative but’s that’s not contained in a digital file.

*************

Tri-X ASA 400

So, we’ve established that film emulation software, while really cool, isn’t completely accurate. At best, it ‘mimics’ the look of film. In any event, I prefer its compromises to the unedited look of greyscaled digital.

Below are the Nik emulations of a number of traditional film stocks. To my eye, some are better than others in recreating the native look of the film: Plus-X, HP5, Fuji Neopan 1600. The Tri-X emulation doesn’t work for me, and I think that’s a result of TRi-X’s contrastiness coupled with its ability to preserve highlight detail, an ability compromised when ’emulated’ by the native limitations imposed on software working with digital files as noted above.

And yes, Wally is an adorable cat, a seven-month-old Maine Coon Cat we found at the ASPCA shelter. Boy’s got a personality, sweet as can be. There’s plenty just like him at animal shelters everywhere. Do them, and you, a favor and go take one home. Best thing you’ll ever do.

The colour shot has a beautifully romantic look that could find many applications. It’s by far the best version of that shot (IMO!).

A problem I’ve seen with strictly digital experienced photographers trying their hand at faux filmic black/white and grain is this: they put grain over what’s supposed to be burned out highlight areas. In other words, they grey down with applied grain absolute white which, with printing film, didn’t happen. It’s an obvious give-away if you know film and printing it.

As for graining up things like Plus X and FP3/4 – they were films you used to keep grain as low as possible and to get it on tiny repros such as in your examples, would mean bloody awful exposures and processing.

Again, it highlights the reality that one can’t leap in with half-understood ideas and just apply “filters” in the hope of getting lucky. One may fool some folks, but not the older guys. It’s also sometimes the case that digital pix are treated with noise or its “effects” and then sharpened more than film would look sharp in those circumstances. Everything has to fit.

Rob

I think you’re right about the color shot. the fuji S5 does beautiful color, and its RAW files lend themselves well to B&W conversion. Its a wonderful camera, destned to be a cult classic f not already. I prefer its 6k output to that from my (gone now) D800.

https://cameraderie.org/threads/adding-a-gamma-curve-to-a-digital-image-thinking-out-loud-and-experiments.38778/

I wrote my own code to convert the 14-bit DNG files output by the M Monochrom to add a Gamma curve and convert to 16-bits. The extra 2-bits preserve accuracy after the multiply operation, it’s a reversible operation- I use a 14-bit to 16-bit look-up-table generated from the Gamma function. I end up batch processing all the files from the M Monochrom, convert to the 16-Bit DNG, then use Lightroom to export to JPEG. All written in FORTRAN…

Very cool, Brian. I’d love to see some converted files. Send me some….

It took some one like yourself Tim to put it in a concise and intellectual way of explaining the differences.

Not all that verbal garbage on social media regarding this subject. Another reason why I read your blogs and enjoy reading them as I am always learning from what you have to say.

Thanks,

Dominique.

My Maine Coon, “Rembrandt Lynxalot Coonflakes” aka “George”, left this world on 11th February.

His dad was a champion show cat, but George liked the home life and he spent thirteen happy years chez Stephen, following my EVERY move. I still talk to him every morning, even though he is three foot under. He was the most unusual cat, with far more dog like character than you would expect from a cat. He did well for a Maine Coon, the breed has a congenital heart defect.

He still appreciated the odd mouse though: http://www.i-shot-it.com/competition-photo.php?id=56ab9f2f08317

Like Rob, I find the colour version to be the most keepable…

But supposing you only had one copy, say the one that when put in context, was your least favourite, the simple grey-scaled copy… Would you mind? Or would you hurl it contemptuously into the bin?

Of course the one advantage of the digital version, it doesn’t take up any physical space, any contemptuous throwing would be a more prosaic exercise.

B&W was my main love when I started photography in the 70’s. But I never was a great printer. Oh, I could print a decent picture in the darkroom but I could always see the limitations and I never felt I was getting the best results. When I began shooting digital I concentrated on color because it was a part of the file. After playing with B&W for a while, I started to realize I actually was printing pretty good B&W pictures for the first time. And, dammit, I actually came to prefer the look of my B&W digital photos to most of the darkroom done B&W photos I see today. The problem I see with most digital B&W is that people tend to look for these canned “filmic” looks. Digital ain’t film and it looks like crap when you try to make it look like film.

From the photos you’ve posted on your site, I can see you’re a knowledgeable and excellent film-image maker. As well, your digital images look better than most I’ve seen. I’m a muddler. I tend to muddle along with a photo in Lightroom, trying stuff until I get it to look like I like it so I can print it (on an Epson, not in a tray). And every photo needs individual work to get it to look its best. Not a programmed formula or film simulation in my opinion. And if it doesn’t look like Tri-X or Acros or FP4, so f-ing what! It might turn out to be a good looking print without needing any sub-classification attached.

I agree with the Dogman. Let film be film and let digital be digital. Both are legit.

Just rewatched a video interview with Gianni Berengo Gardin where he recounts a youthful meeting with Ugo Mulas. Impressed, he says beautiful! to all the photos Ugo shows him until the latter stops, and says call one more picture beautiful and I shall throw you out of my house. Embarrassed, the young Gianni says well, they are beautiful, how else can I comment? Mulas says to him: there is beautiful and there is good; beautiful is surface and good means the thing has achieved meaning. I rather make good photographs.

IMO, digital allows too much local contol over a photograph. You can work on it for hours until you lose all sense of what you’re actually looking at, and so on the assumption that those hours are productive, out it goes into the world.

Film photography, on the other hand, allowed far less local control in normal circumstances, and so it held some semblance of honesty when you were done processing it.

So, in the sense that Mulas was thinking, how many good photographs do we come up with in a year? Not only has digital democratised photography, it has pretty much turned it into candyfloss. Is that a good thing?