Film photographers never much cared about bokeh. The first time I think I even heard the word was when we were well into the digital era, probably on some internet forum, where the hive mind argue vehemently, and endlessly, about some non-sensical brain-splitting, optical hair-splitting issue, the functional analogue of mediaeval theological debates about just how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. When it comes to bokeh, what everyone agrees is this: whatever lens you buy, it’s got to have beautiful bokeh. Not angry bokeh, or harsh bokeh, or clinical bokeh. Beautiful bokeh.

Bokeh is a digital phenomenon, a photographic meme that’s taken wing with the digital herd’s overriding obsession with optics. Or maybe, upon reflection, it isn’t so silly, but rather points up what I see as an inherent flaw in the nature of digital capture – the sort of transparent, ultra-lucidity of digital files, their noiseless purity that just looks….false. I can best describe it as a certain lack of presence, a sterility in continuous digital tones, obvious in how digital capture renders clear blue skies, skies that film renders, even when blank, with a certain heft and fullness. Digital renders skies thin and transparent, lifeless in their plastic perfection.

And I think this might be why we are now obsessed with bokeh: it’s this sterility in the very nature of digital capture that has brought to the fore our obsession with ways of masking it.

*************

Narrow depth of field and subsequent emphasis on bokeh is a function of photography as a process. It’s not an organic offshoot of the human experience of seeing, but rather a photographic artifact, a result of the process of capture itself. It’s certainly not replicating a natural way of seeing. It’s what philosophers refer to as a “construct,” produced by the characteristics of photographic optics.

But so is grain. We don’t see grain. Grain is a traditional artifact of the film process. Grain gives that patina of distance, the step back from the real that helps us see the obvious – photographs aren’t transparent windows onto what is “out there”, they’re opaque at best, more a mirror turned back on the photographer than the view out if a window looking out.

I’m not advocating the position that an emphasis on bokeh (or grain) is somehow a violation of photography as a transcription of really. The underlying premise of that claim would be that there is one true way to recreate something photographically that corresponds to what is actually there, and the photographic effect we call bokeh is a perversion of that transcription. Of course, that notion is nonsense, based on the premise that photographs do, or even can, accurately transcribe reality.

The idea that photos accurately transcribe reality is a “common sense” opinion the average person holds about the basic integrity of the photograph as a reflection of what is “out there.” But it’s wrong. Some cultural philistine once sought out Picasso while he was resident in Paris. The guy wanted to tell Picasso he wasn’t a good painter because his portraits didn’t “look like” the people he was painting. Picasso asked him what he meant by “what people look like,” to which the philistine pulled a small B&W photo of his wife from his pocket, to which Picasso replied “so, your wife is very small, completely flat, and has no color?”

*************

So, bokeh is an artifice, added by the process itself, not inherent in how a scene represents itself to human vision. But so is grain. Bokeh is a relatively new phenomenon, created by fast optics that easily express – some would say overemphasize – it. Grain is produced by the silver halide process itself. Different processes, different effects.

There was a time, in the pre-digital age, when photographers tried to minimize grain, seeing it as a flaw in the process, or, at least, accepted it as the cost of shooting ‘high speed’ films in available. light. If you look at Robert Frank’s American photos they’re grainy, not, I suspect, because he meant them to be that way but rather because it was a necessary effect of getting the shot at all. Of course, if you shot extremely slow films like Panatomic-X or Pan-F, you could largely avoid it up to a certain point, but the slow ISO of those films made the trade-off difficult. Hence, the ‘grain-less’ C41 films like Ilford’s XP2 Super. Ilford actually manufactured two “chromogenic” C-41 compatible black-and-white films, their own XP2 Super and Fuji’s Neopan 400CN. Kodak produced a similar film, BW400CN.

These films worked like color C-41 film; development caused dyes to form in the emulsion. Their structure, however, is different. Although they may have multiple layers, all are sensitive to all colors of light, and are designed to produce a black dye. The result is a black-and white image with no silver halide grain particles.

*************

As a film photographer, I prefer some grain in my images. Certainly, now more so in the digital era when digital capture makes the ‘grainless’ look normal. I love the grainy look of Robert Frank in London/Wales, Valencia and The Americans. But I don’t think he was thinking of graininess when he photographed. He was just trying to get a workable negative. It’s ironic, then, that that heavy graininess has become so associated as an integral part of the work once digital capture came along. This emphasis on grain – which I’m prone to – is something I developed in the digital era. Grain gives me a way of giving a certain heft to the image; it’s why I typically shoot film above its box speed and develop in speed-enhancing developer like Diafine. I didn’t do that back in the day. I do it now because I think it’s what differentiates the film look from the digital look. It’s also why I run all my digital files through Silver Efex to, at a minimum, add grain structure to an otherwise ‘flat’ digital file. In this sense, grain has become as much a function of digital capture as has the emphasis on bokeh.

You’re absolutely right: bokeh was a new one on me, too. The closest that I think I came to thinking about it, namelessly, was when I used my 150mm Sonnar on the ‘blad, outdoors. It wasn’t really bokeh, anyway, it was the marked shape of the diaphragm that appeared in some shots. I though it looked pretty cool; added something extra. Thing is, straight fashion photography didn’t often mean my going into wide apertures: the need was to show lots of detail. I spent a lot of time at 125th and f8.

An exception, always, was the 8/500 Nikkor Reflex: its doughnuts bokeh was the reason for buying. I discovered that if you focus beyond a distant subject, it (the subject) goes out of focus in a quite interesting way. You can, obviously, control the degree of OOF effect by looking at the screen.

Yes, my main thought about grain was usually how to keep it as low as possible, unless I thought it was going to add some atmosphere to a shot. That decision was made by selecting either 125ASA or 340/400 ASA stock. Once that decision was made, I thought no more about it. I never did go the way of over-developing, because that brought problems of blocked highlight that I didn’t often want. However, there was – and probably still is – a general penchant for very white faces in fashion photography (black/white) during the period when I was in it. That’s so much easier to pull off in digital. I think the worst thing about digital comes after the shoot: all that sitting time at a computer. I have grown to hate it, which perhaps has added to my mojo going AWOL. The user experience with the little iPad, as used here and now, slouched on the couch, is quite different and most pleasant, even if it means a sore back when I go to bed.

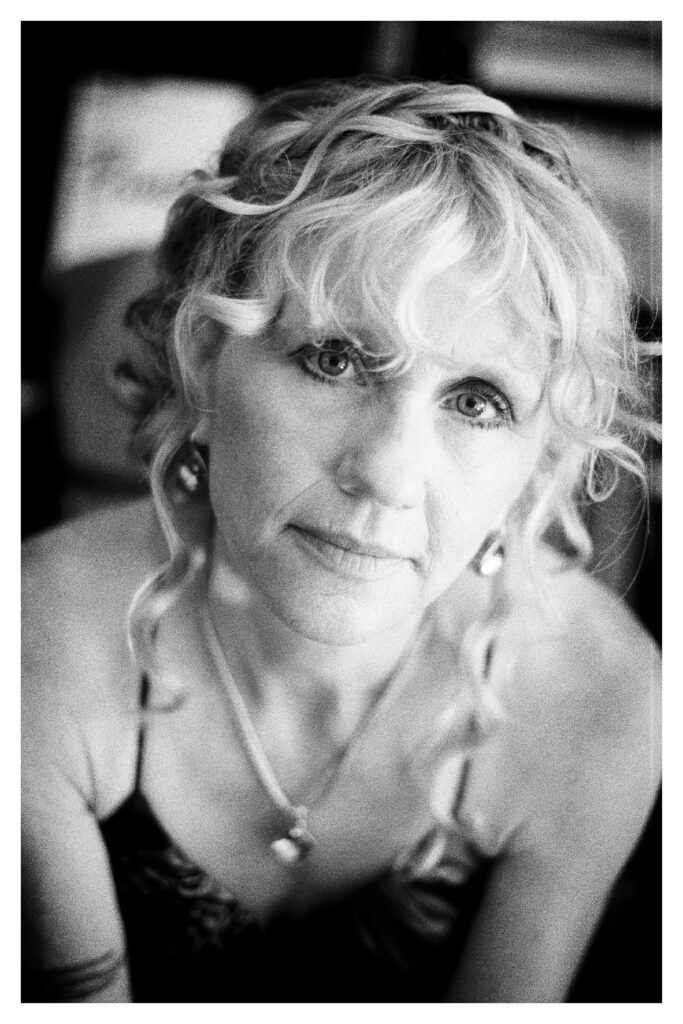

The expression on her face, to answer your rhetorical question :).

I encountered bokeh for the first time watching a youtube video on photography for my entertainment in 2019. I think you must be right, some of the comparisons used vintage lenses but all were mounted on digital cameras.

Prior to that, blur occurred when you missed focus, or the shutter speed was too slow for the subject matter, or you were indoors at your kid’s party trying to get pictures without a flash using ASO [sic] 400 colour film.

Except once, there was this memorable article in Darkroom & Creative Camera Techniques of July/August 1995 in the Leica Mystique issue by Carl Weese talking about Leica lenses. He talked about his photo ‘The Ganges, Benares, India, 1969’ taken at night and the beautiful coma defects found in a 1960s 35 Summilux. But he wasn’t talking bokeh.

Swirly bokeh from old lenses, highlights of sharp edged flattened disks all over the background, I think would have been edited out of photobooks of the period as distracting. I can’t think of a single example of such a photograph. What I will say is that lenses with such swirly bokeh often give horrible photos on digital, I have images of ducks on water in strong sunlight taken with an old long lens which results in pinpoint overexposure, i.e. white dots, ringed with chromatic aberrations, from reflections off the water, and distracting jittery backgrounds which are either absent or much better controlled with long lenses from the digital era. Bokeh to me is an epiphenomenon of lens design which has been placed in centre stage.

I have a photo of one of my kids taken on Tri-X printed at 10″ x 15″ that is completely grainless to the astonishment of my father-in-law. You can view it at any distance. It was developed in full strength XTOL as one does, scanned at 3000 x 2000 ppi by the local shop on their Noritsu, so when you pixel peep you see pixels before you might see grain, and consequently the photo is grainless. It does not look like any digital I produce, though.

To me ‘bokeh’ is just a blurry background that isolates the point of focus and sometimes looks kind of cool. Grain is a signal that any film photograph is just a simulacrum made up of little specks that were transformed by the light rays from real life outside the camera. There’s no there there, it’s only a detailed sketch of what the lens could see while the shutter was open.

With film the distinction was clear, but digital imaging increasingly offers the pretense of reality. That’s all it is though… a pretense. Maybe that’s why I still use film quite a bit and have no interest in ultra high resolution digital sensors.

Be sure to include this chapter in your “Tutorial for those Digital Souls Desiring Authenticity, Process and Tactility”

To elaborate on Bill B’s answer to the question, it’s the eyes.

Bill and I are looking at the entire image, the whole, not the elements. Arranging the elements is the job of the creator and the success remains in the arrangement. I’ve commented before that we “creators” sometimes are not even aware of how we do the arranging–it’s just a coming together naturally for us.

I love reading about optics. I’ve bought my share of really nice lenses simply because they have certain characteristics I find fascinating. One of them is the Nikkor 85/1.4 AF-D, sometimes referred to as the “Nikon cream machine” based on its bokeh rendering. I like this lens for how it handles the out of focus areas in photos. It’s very lovely in my eyes. But it’s only one of the numerous pieces that make for the whole. I don’t think much about it when shooting. I slap that 85mm on, knowing it will do what it does and I can go about shooting pictures. When I look at photos, I don’t see the bokeh or the grain or the contrast or the shadow detail. I see a picture and, if it’s put together well, I see a good picture. I might deconstruct later but the picture is what is important. That’s why I see a lovely woman in the photo of your wife, Tim. Especially the eyes.

Agreed.

Tim, the images of your wife speak volumes.