“Images are not quite ideas, they are stiller than that, with less implication outside themselves. And they are not myth, they do not have the explanatory power; they are nearer to pure story. Nor are they always metaphors; they do not say this is that, they say this is.“

Robert Haas, Twentieth-Century Pleasures (1984)

I’m just done reading a book it’s taken me 42 years to read, The Man With the Golden Arm. Great book, beautifully written by Nelson Algren, a once-famous author now thoroughly forgotten. I bought the book in 1977. I bought it because Algren was currently living in the next town over, Paterson, and was somewhat of a local celebrity, a Chicago born critically acclaimed writer who decided to move to Paterson just for the hell of it. Knowing Paterson, that took guts. The book is about junkies in Chicago in the 1940’s. It won the National Book award when it was first published in 1949. Hemmingway said it was one of the best American works of fiction of the first half-century. Algren, who went on to also write the cult classic A Walk on the Wild Side in 1956, was apparently a pretty interesting guy himself, a self-taught author, self-professed Communist and Anarchist who hung out with, and wrote of, Chicago’s junkies and prostitutes and petty criminals ( he also carried on with Simone de Beauvoir, the French feminist philosopher and girlfriend of John Paul Sartre, throughout the 50’s and 60’s; anyone bad-ass enough to be banging Sartre’s girlfriend deserved attention).

That book sat on my shelves, unread, until a few weeks ago. Innumerable times over the years I’d open it, read a few of its dense pages, and put it down. It simply didn’t grab my imagination. And then, a week or so ago, I told myself I was going to read it. Period. The time had come. So, I did, and I loved it. In hindsight, it was a work that needed 42 years of my maturation to fully appreciate; Algren’s beautifully intricate writing style, full of metaphor, doesn’t lend itself to topical reading but requires your full attention. Given that, it’s a remarkably evocative novel, the writing easily lending itself to a vivid imagination.

Yesterday, I rented the film version, starring Frank Sinatra. Bad idea. Not only was it a shitty movie, it somehow poisoned my delight in the book itself. As a dedicated reader, I’ve learned one thing about film adaptations of books I’ve previously read: don’t watch them if you want to retain the imaginative enjoyment you derived from reading the book. That’s because, once viewed, irrespective of the quality of the movie itself, the movie’s image asserts its hegemony and wipes from your mind’s eye how you as a reader imagined the characters and unfolding plot. The visual image offered by the movie now has become truth, something more brutely powerful than your own memory and imagination. Like it or not, the movie’s interpretation is now mine. In fact, after seeing the movie, I can’t even remember how I had imagined the story I’d read. It’s gone, bludgeoned unconscious with the literalness of the photo image.

My experience with Algren’s book – and then watching the movie – points to a larger problem of images, that of how their literalness can interfere with the workings of our imagination. As noted by Owen Hulatt, a scholar of the cultural philosopher Theodor Adorno, the more our reality is comprised of the factuality of images, the less room there exists to exhibit ‘imagination and spontaneity’ – rather, images “sweep us along in a succession of predictable moments, each of which is so easy to digest that they can be ‘alertly consumed even in a state of distraction.”

*************

Photographic images are everywhere, increasingly curated for us; algorithms decide what we see, when we see it, and how we see it. While this is great for those who want to influence us (advertisers, politicians etc) this surfeit of images and our easy familiarity with them has caused us to become imaginatively lazy. Why? In Roland Barthe’s mind, what defines the image is its stubborn factuality. Photos are traces of things, real things out there. In this sense, they tell us a truth. I would submit that photographs give us, at best, an impoverished ‘truth,’ a truth of brute ‘facts’ that in its literalness leaves little room for imagination. This has nothing to do with popular criticisms of altered images and photoshopped realities. It’s more existential than that. Photos are “unisensory” i.e. no other sense nor the imagination itself is needed to understand them. Given they are unisensory, a photo cannot convey the full depth of experience, because nothing other than the visual is required to grasp them.

In his cult-classic The Origins of Consciousness and the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind (1976),** psychologist Julian Jaynes contends that imagination is fundamental to consciousness itself, or rather, more precisely, consciousness is imagination in the sense that all consciousness depends on metaphor, which is itself a type of imagination. Metaphoric thinking = this is like this is like that. Sven Birkerts, in The Gutenberg Elegies (1994), notes the inextricability of metaphor and imagination: ‘Metaphor requires a perceptual power and ability, a re-seeing, a re-analogizing’ … fostered through a ‘depth of attention’ that, in turn, breeds imagination.” Jaynes would say that’s the architecture of our minds. Reality is comparison, and comparison is imagination.

Metaphoric comparisons are not only part of the architecture of language and mind but they are elemental to human thought and imagination. To make sense of new things – to give them a reality – we compare them to other things, familiar things from our environment, our culture, our identities, things that we previously came to conceptualize by doing the same, ad infinitum. It is these mental connections that give rise to consciousness itself, which consists of the primary experience between ourselves and the world, as well as sensitivity to the nature and details of that experience. Metaphor is how we mentally access and internally narrate language, image, and sensory experience. And, it’s the basis of all human creativity. Aristotle, speaking of the poet, claimed that “the greatest thing by far is to be a master of metaphor. It is the one thing that cannot be learned from others; and it is also a sign of genius, since a good metaphor implies an intuitive perception of the similarity in dissimilars.”

*************

So, we’ve established that metaphorical thinking is really important and yet, in our hyper image-saturated world, I’m starting to suspect we are losing the imaginative power to create and find meaning through metaphor. As always, kids are the bellwether, kids who’ve found their reality via web-based versions of the real, the punchy over-saturated image or the 40 word tweet. Consider the experience of poet Sara Holbrook , who wrote a recent article for Forbes titled ‘The Writer Who Couldn’t Answer Standardized Test Questions About Her Own Work (Again)!’ which documented her frustration with her students’ desire to “dissect” her poems e.g. understand the ‘best reason’ for a simile she chose to use etc . “Forget joy of language and the fun of discovery in poetry;” what students wanted was “line-by-line dissection, painful and delivered without anesthetic,” as one might approach the dissection of a frog. This sort of literal, factual dissection of artistic creations was what they knew, having been bred into them as heirs to a culture where information is increasingly gleaned via the visual, and factual investigation has replaced imaginative interpretation as the standard by which creative expressions are critiqued.

In 2014, a Harvard research team set out to study the decline in creativity among high-school students by comparing both visual artworks and creative writing collected between 1990-95, and again between 2006-11. Examining the style, content and form of adolescent art-making, the team sought to define a potential ‘generational shift’ between pre- and post-internet creativity. What they claimed to find was that the creative-writing of the two groups showed a “significant increase in young authors’ adherence to conventional writing practices related to genre,” what they defined as a trend toward formulaic styles without significant imaginative deviation, while their visual creations were informed and inspired by “expansive mental repositories of visual imagery” [think: stock photography] easily available in the public domain. They noted in both “a significant increase in and adherence to strict realism,” and a turn away from metaphoric thinking. The team cited standardized testing as a likely source of this lack of creativity, but also the proliferation of visual culture and its role in new modes of casual communication – in other words, visual literalism (“selfies”, emojis etc) standing in for words and feelings.

*************

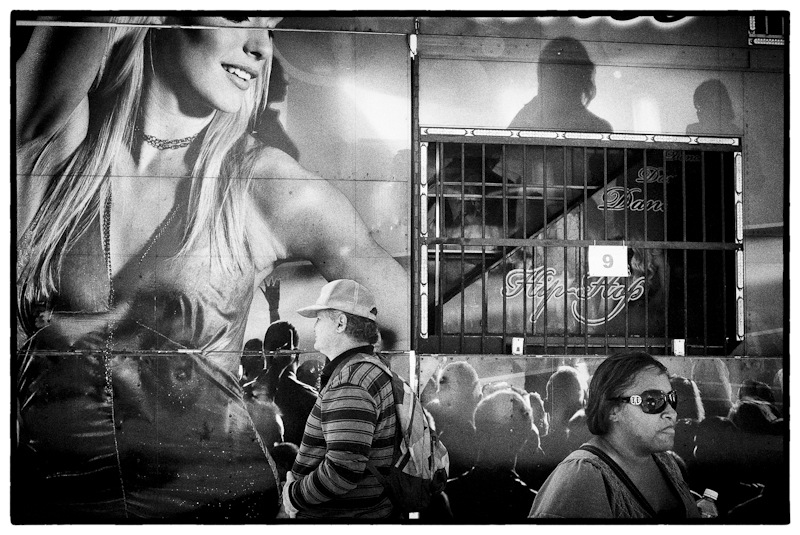

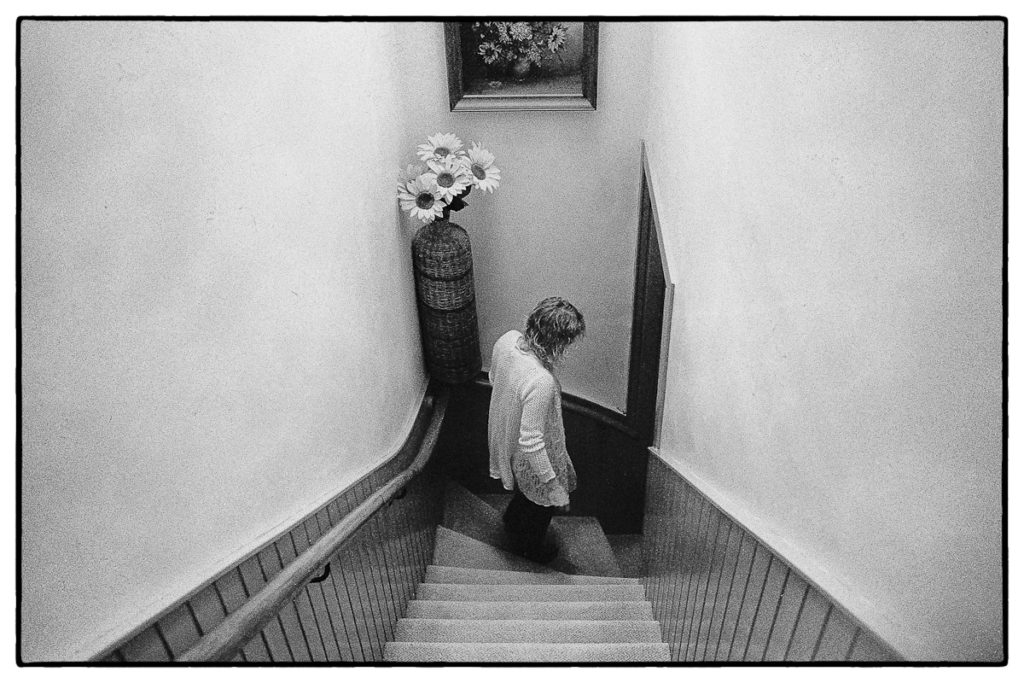

What’s the point of all of this? Hell if I know. The fact that I’m on my third bourbon, neat, isn’t helping to clarify things, except I do see a transition I’ve been making – probably subconsciously in response to the issues I’ve articulated here – in my photography. I was trained as a documentarian, and my idea of the photo has traditionally been less a means of creative expression than as a vehicle to transmit knowledge. However, lately I find myself more focused on producing images that possess ambiguity, that need to be read into. Maybe it’s a subliminal response to what I consider all the regressive trends currently ascendant in photographic culture – sharpness, image quality, technical brilliance etc – and in visual culture generally, the use of images as a means of documenting what is presented as “the real” [selfies and all the airbrushed nonsense people post on social media sites]. I’m increasingly getting to a point where I want my photos to be explicitely about the “not real,” about what might be imagined as opposed to what I claim is. That’s the place I want to share, if that’s possible, to make of stubborn facts something more than just what is via the viewer’s imagination. That’s what Nelson Algren did with his writing. Of course, he died broke and friendless in a cold-water flat in Paterson, New Jersey, completely forgotten.

Time for another bourbon.

** One of the truly mind-bending books I’ve ever read. Every educated person should read it at least once.

Views: 999

In my case rather like buying and reading a copy of Robert Franks America, knew it existed , obtained one, teasing myself notviewing yet, but this article making me that viewing tonight. Thanks

I’m going to deviate from your question. Our daughter is a university professor of Illustration and Design. She’s also a published artist, works on commission for private collectors, etc. She know her schitt (dad bragging a bit, but…)

In the 12 years she has worked on the post-secondary level, she has noticed the following decline in the many of students she teaches:

1. Lack of curiosity about the world/space they live in;

2. Decline in basic motor skills (they can’t manipulate an x-acto knife, etc.)

3.Reluctance to venture into the ‘real world’, i.e., they won’t hop on the T (Boston Subway) to venture from their dorms in Cambridge into Boston;

4. Increased used of app based services: food delivered to their room via GrubHub, purchasing from Amazon rather than taking a 10 minute walk to the art store.

5. Difficulty with face to face communication (crits, talking to professors,etc.)

6. Copy rather than create to avoid any negative response to their work, etc.;

This has been a topic over the years shared with both my wife & me (Both retired educators.)

It’s discussed and worried over at faculty meetings, department meetings and at the upper echelon of the university. They are flummoxed.

Creativity is on the decline.

Very interesting, Dan.

Indeed, very interesting, but perhaps not surprising given the ‘virtual world’ many now inhabit.

Actually, I do find that both surprising and worrisome. How is it possible to even enter University with those traits? The word “narrow minded” is on the tip of my tongue-in-cheek, but I realise that has a very negative connotation.

The short reply: funding for arts programs in public schools is drying up.

The long answer: I taught in the public schools for 35+ years. My subject areas included photography, graphic design, architectural drawing and CAD. It was a small school, about 350 students (our district was lower middle class/working poor.) The wait time for my photo classes was two years. I retired in June of 2012. By September of 2012, my rooms had been stripped – 12 Beseler 23C enlargers in the dumpster, the computers were disposed of as surplus, and two rooms I used as classrooms were converted into a weight training facility. The darkroom was made into a storage room. Someone broke into the storage closet where all the cameras were kept (35mm up to 4×5) and stole the equipment.

At least the art program still was functioning. This June (2019) I got a call from the art teacher (she was in tears) saying the school eliminated the art program, and trimmed the music program to a half-time teacher. This is not a wealthy district…if it wasn’t for us, most of our students would never be exposed to the arts. BTW, this is in blue-state Connecticut.

Our daughter teaches a basic class on tools & techniques so the incoming 17 & 18 year old’s learn skills that should have been taught in HS. You don’t need to use a x-acto knife if you’re learning coding, I guess.

Another BTW: medical schools are seeing the same lack of basic eye/hand skills in their medical students.

Thanks for enduring a long reply.

If you are changing direction, Tim, it’s because in the end, personality will out.

In my case it harkens back to ’59 or so with the discovery of Saul Leiter on the pages of one of the Popular Photography Annuals (they did two versions, one colour-devoted). He made quite an impression on me, and then he disappeared from my radar until a handful of years ago.

I’d been at a complete loss, photographically, from the day I finished my last pro photographic assignment; I’d bought a digital camera and had no idea what I was going to do with it. Then, courtesy the Internet, Saul popped up again and, with him, my rekindled interest in his style of street, which was more about the look of the thing – the street, the street furniture – than of people. So there I was, an interest reborn in my dotage. Almost all my work from then onwards has been about the street and the hidden motifs that might or might not exist outwith my own belief that I have seen and photographed them.

Maybe you can discover something about yourself too, by wondering what really made you want a camera in the first place.

Insofar as today’s people and their communications go: I tend to eat lunch out most days, and the times I see an entire family at a table, heads down, fingers racing on cellphones, makes me wonder how the family came to be: procreation by App?

At least for photography, black and white can help in being clearly less literal, opening the door for imagination. Of course, for masters of colour, colour can be subverted for metaphor as well…

I generally think of colour photography in terms of commercial photography.

If anything, I feel that colour is usually a distraction, a visual perfume; very few photographers seem able to think of colour and photography as distinct entities, they just shoot the scene which naturally always happens to be coloured – hard to find anything in life that is devoid of colour. When you do that, you can hardly feel you’ve created anything much beyond a reporting of what you saw when you were there, wherever there was.

Those others, more gifted in my opinion, who can take a little bit of coloured something they see and turn that into something unique, a statement of their own, let’s say, they do deserve some kudos. Finding a simple block of colour and, by selection, creating a purely graphic design from it, feels worthy of respect. Not easy.

Yeah, black and white gives one an instant remove from stark “reality” but is not, of itself, worth anything if the conversion has not also made its own visual statement. There is every bit as much crappy b/white around as there is lousy colour.

The big problem that touches all photography is that not everything that gets photographed is interesting because it has been photographed. If legend is to be believed, it’s what drove a certain American street photographer called Garry Winogrand to shooting street simply in order to see what it looked like photographed. With thousands of cassettes behind him, and certainly those 10,000 hours, he appeared to be no further forward in his ability to know before making the shot.

As William Klien remarked when told he had a good eye, it takes more than that.

There’s work that floats my boat and work that doesn’t.

B&W or Colour doesn’t matter, as long as it gets me there.

First I’d need a boat to float, and realised that any boat I thought worth the having was way, way beyond my means.

Depressed me for years, such beauties under my nose every day, but utterly out of sight insofar as my pocket was (and is) concerned.

But hey, in the end, some brilliant rationalisation made it okay. Wonderful thing, self-deception!

🙂

On the subject of Emoji’s. It’s rather disturbing to see the multitude of variations churned out for purposes of USPs. Think about it for a sec.: what was the original purpose of an emoji? To provide a symbol for universally recognisable emotions. Emotions irrespective of age, gender, gender-affinity, background, race, upbringing, intellect, whatever.

Universal. As in: non-discriminating. Recognisable.

And then suddenly we need variations because somebody who doesn’t exactly grasp the concept of political correctness, thinks it is more politically correct to actually do provide discriminative emoji’s.

That’s the level of philosophical foundations we have reached.

Things will improve when social media is banned or burns out. It has turned into the most pervasive, largely negative influence in the world. It gets governments elected, kids bullied; possible suicides driven the extra yard, and people dumbed down below the lowest common denominator.

I managed without it and still do; I have never tweeted a tweet, faced a Facebook, had a single instance of Instagram. And you know what, I don’t feel any the worse off for it. If anybody needs to get in touch they have two ‘phone options, a website and e-mail. If that’s not enough, then they have confused me with somebody else of the same name. Or, more likely, they have just become confused.

With all those distractions, how do they manage to get anything done – if they do? I look here and, now, in but one other photo-related site. Doing that takes up a lot of time. The Internet offers many things to photographers, especially thousands of pictures by one’s favourite artists; for me, that’s plenty. I don’t need to know what every member of my family is doing every hour, on the hour; frankly, I think I’d often rather not know – and it’s probably mutual!

Rob

I have a flickr account, an email address & you can call/text me on my cell. I know my large dinosaur tail wrecks havoc when I’m out & about. Our daughter wants me to open up a Instagram account for my photography, but I don’t see how it will improve my life. All this stuff is a distraction and sucks up creative energy. But, I am an older guy, so I don’t know what I’m missing I guess.

Hell, even my fone is dumb.

🙂

Throughout the past couple of centuries, increasingly effective photo, cine and video technologies have made many of us into very lazy lookers. If brilliant and realistic artificial imagery can be effortlessly and endlessly experienced on the outside, why develop personal skills of imagination and visualization on the inside?

A similar effect can be observed in almost every aspect of modern culture as we eagerly surrender our native agency to mass-marketed machines, screens, programs and algorithms.

Ironically, one of the most vivid depictions of this phenomenon that I’ve seen is in the animated film “Wall-E”, the product of an elite team of imagineers at Pixar. They are the cream of the creative 1% whose job it is to continuously light up the eyeballs of the passive 99%.

Whenever I watch a recent Disney or Pixar animation I’m left with the impression of great storylines but of visual sterility. Long gone are the classics and the associated draughtsmanship.

Illustration vs. computation?

Of course; the more we surrender to the machines the less we will end up doing ourselves and, I guess, enjoying. And that doesn’t even look at what we may no longer even have the skill to do in the future, having allowed it all to atrophy away as if it didn’t matter

Caught a brief look at an Amazon centre the other day on television: huge space, robotic lines doing the work. And the ‘bots didn’t even pretend to look human-like. This is the penultimate scene of the play.

🙁