Rungis, Paris, 2004. Sometimes you’ve got to look hard to see what’s in front of you

If I were to describe, as best I’m able, what I’ve spent a lifetime of photography doing, it would be this: I’ve tried to document “the plain sense” of the things that constitute my life. Putting words to something which is intuitive and ineffable, it’s the intellectual equivalent of trying to squeeze an elephant into a mason jar – it doesn’t capture all of the buried motivations, but it gets as close as words allow, so it’ll have to do. I’ve always respected Garry Winogrand’s explanation for why he photographed things, “to see how they look when photographed,” which is as good a no bullshit, anti-Artspeak explanation as I’ve yet heard.

All of this assumes my photography has any purpose. I can’t articulate any overarching explanation for why I photograph or why I photograph what I photograph. Attempts feel like ex post facto justifications for something that can’t put into words, the logic behind it being ineffable. My photography just is; the subject creates itself. I point the camera at things that make sense to me to photograph. Any needed rationalizations come later, at the point of editing, selecting, sequencing, articulating. What I’m left with defines what I’ve seen and how I’ve seen it.

*************

Portland. I love this Photo. Why? Hard to Say

There’s nothing more pretentious than an artist explaining his work. Invariably, the explanation sounds silly, forced, as if he has no real understanding of what he’s been doing. Some of my most awkward moments have been those times when a gallery visitor has asked me what a painting “means.” Anything you say will sound pretentious and foolish.*** The best response I’ve been able to come up with is “I don’t know, you tell me,” except that’s not really correct either. The honest response would be “I can’t articulate its meaning…but I know what it is. As for you, interpret it as you will.”

Our creative motivations are often opaque to us, but always larger than the restrictions imposed on them by words. Putting words to them often circumscribes rather than illustrates the work and, as such, weakens the work itself, boxing it in with artificial constraints. Dragan Novakovic, the subject of a recent post, described the impetus behind his early 70’s British photos, a coherent body of photographs if there ever was one: “I wish I could tell you that these photos are the fruit of a well-thought-out project and expatiate upon it (projects and concepts seem to be all the rage these days), but the truth is, they are all completely random shots.” I admire him for saying that. It takes courage to admit your conceptual naivete; in Mr. Novakovic’s defense, his photographs are so good they need no explanation. Whatever ‘naivety’ Novakovic possesses isn’t born of ignorance but rather his intuitive understanding that whatever he’s done – inspirationally and procedurally – can’t be reduced to an explanation. The explanation is the work itself.

One of my favorite recent photo books is Dive Dark Dream Slow by Melissa Catanese. No words, just a sequence of vernacular photos from the photography collection of a guy who collected anonymous 20th century “found” photography, the kind of photographs we paste into albums or stash in boxes stored in the attic along with other detritus of our lives. Ms. Catanese is the curator of the book in the sense larger than simply “editing” it. The work is really her’s, in that through her selection, sequencing and presentation of the photos she’s created something unique to her, something apart from the intentions of the various photographers or of the collector himself. What it “means”? Clearly, it “means” something to Ms. Catanese given the constraints she imposed on the materials. As to what that meaning is, she’s not saying, or, more precisely, she seems to be saying “It means what you make it mean.” And that’s the fascination of it. We as viewer get to give it a meaning.

One of my favorite recent photo books is Dive Dark Dream Slow by Melissa Catanese. No words, just a sequence of vernacular photos from the photography collection of a guy who collected anonymous 20th century “found” photography, the kind of photographs we paste into albums or stash in boxes stored in the attic along with other detritus of our lives. Ms. Catanese is the curator of the book in the sense larger than simply “editing” it. The work is really her’s, in that through her selection, sequencing and presentation of the photos she’s created something unique to her, something apart from the intentions of the various photographers or of the collector himself. What it “means”? Clearly, it “means” something to Ms. Catanese given the constraints she imposed on the materials. As to what that meaning is, she’s not saying, or, more precisely, she seems to be saying “It means what you make it mean.” And that’s the fascination of it. We as viewer get to give it a meaning.

************

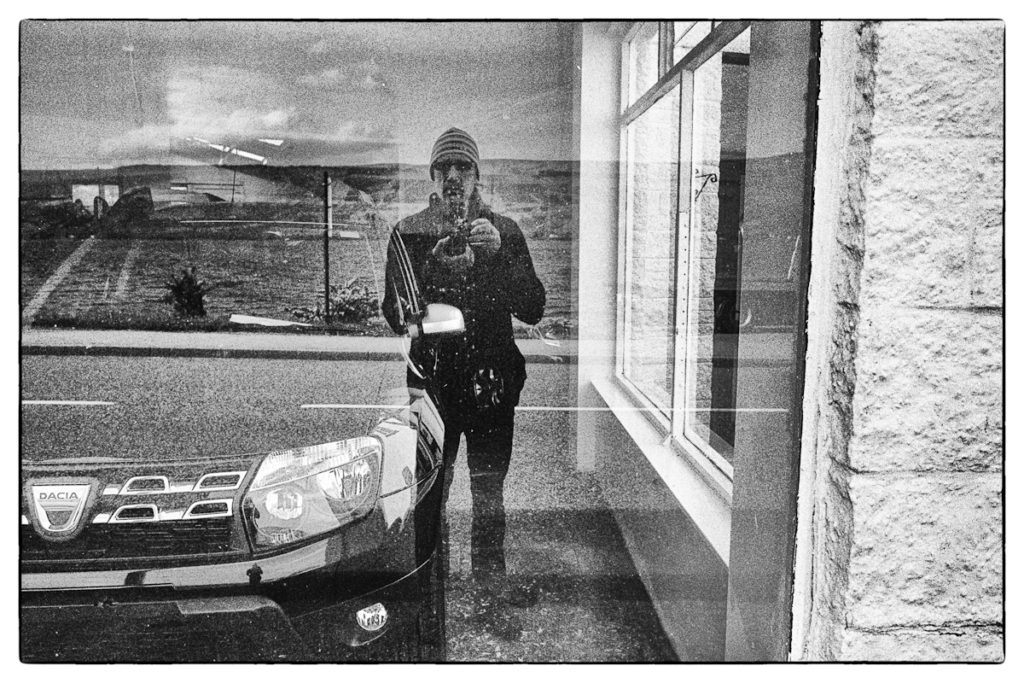

Loch Ness, Scotland 2016. There’s a monster down there somewhere…or so I’m told.

Photography, for me, is an activity in service to an internal, idiosyncratic dynamic. I’ve never made photographs for someone else’s consumption or delectation; I’ve made them to give exterior form to something interior. Hence the doing of it itself has been the payoff, sort of like going to therapy. Certainly there’s a sense of wanting to do it well, but ‘doing it well’ has little to do with what other people think of it, which to me is largely irrelevant. Doing it well means feeling as if what I’ve created expresses some logic internal to me. It’s got to resonate with me. If it does, I consider it done well; if it doesn’t, it isn’t, even if other people like it.

The reason why photography has interested me for so long is because it’s not been ‘about’ anything. I’ve never viewed it as a means to anything, and when I’ve put myself in a position to view it as a means to make a living I’ve quickly, and radically, lost interest. Whatever it is, it isn’t about that.

So, with all that said….I’ll try to articulate what I’ve been trying to do in a lifetime of photography. If it is anything, its been my attempt to locate my self, to give it contours by locating it in a specific time and place [see how pretentious that sounds?]. It’s been my attempt, to document what was (is) me. At heart I’m a documentarian. Anything said beyond that will just muddy the waters, so don’t ask me to explain.

*** My Artist Statement, generated after a few bourbons:

Ever since I was a student I’ve been fascinated by the ontology of mind. My work – scattered across various media yet forming a coherent whole – explores the relationship between subjective profundities and banal, prolifigate experience. Influences as diverse as Homer, Pynchon, Schopenhauer, van Gogh, Joyce, Aristotle, Coltrane, Pollock, and Pound inform my creative narratives. What started out as naive childish hope is now corroded by the hegemony of time, yet it has been leavened by the rich fund of common experience and memory. My work is the synthesis of these things, a re-imagining of what time sweeps into the past, the flux of phenomena screened through the bounded conceptual schema that is me, leaving the receptive clues to solipsistic meaning, assuming, of course, that we, in radical subjectivity, may ‘share’ a solipsism in any meaningful way.

Views: 1064