In my quieter moments, I’m finding myself more and more averse to photography. I’m pretty much sick of it. That’s what too much of a good thing will do. I’m overwhelmed by the constant bombardment of images via the internet, on my phone and computer, all made effortless by cel phones. Images have no value anymore. They’ve become the visual equivalent of junk mail, usually now in the service of someone’s idealized version of themselves or their lifestyle.

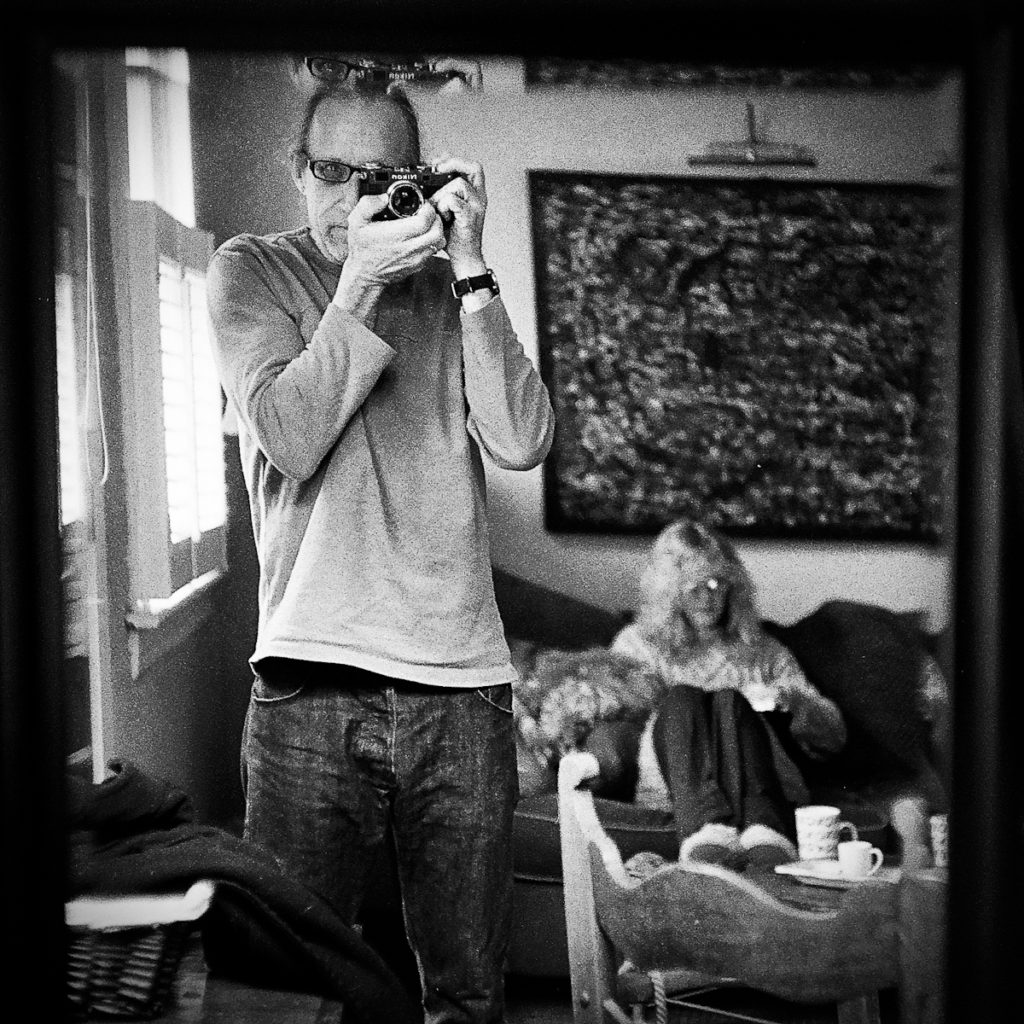

I’ve found myself painting again, probably because I’m increasingly frustrated by the lack of satisfaction photography offers me as a creative outlet. The photo above is a case lesson in why. I took it with a large film camera in 2005. I thought it was pretty cool, so it hung in my house. 15 years ago I could think it might say something about how I see things, something unique about me, both my creative vision and competence in the medium as a means to accomplish that vision. Now, it’s just another phone pic with a filter, something a 12 year old can do with an iPhone. Tell me why anyone should be impressed or even care.

And then there’s the sheer volume of images constantly inundating me everywhere. I’m bombarded with vulgar, banal and stupid images. It’s worn me out. I want to go back to a time when a single picture could move me with its unique beauty. Usually, the photos that did were relatively small and framed and hung on a wall someplace special. They were simple technologically – usually black and white – but they felt like precious jewels. See, for example, the exhibited work of Jacques Henri Lartigue, Walker Evans or Josef Koudelka. These works enriched my life, maybe because they were rare and beautiful and thus possessed a value that transcended their aesthetic worth.

Now, nothing can have that value anymore.

*************

James Lovelock talks of the serious malady affecting ecology, what he calls ‘Disseminated Primeatemaia’, the “plague of people” that threatens to overwhelm ecological balance. I immediately thought of the photographic analogy, ‘Disseminated Photomaia’, the plague of images overwhelming us. I’ve elucidated its subjective effects above.

This plague of images contains the kernel of a more existential transformation as well. It threatens to overwhelm and transform our conceptual reality. If you think about it, this is a plague unique to industrialized modernity. Prior to the 19th century and the advent of technologies of inexpensive reproduction and dissemination, images were rare things, encountered in churches and, more rarely, as artistic creations in the service of social and/or political power. Your average peasant very rarely encountered images in his daily life, maybe 10-20 in his lifetime. We encounter that amount every minute or so.

Unfortunately, we haven’t yet really internalized what this has done to our understanding of what’s ‘real.’ We naively consider ‘reality’ as being separate and distinct from images that reflect it; we think ‘reality’ creates its images. In fact, it’s the opposite. Even prior to the internet age, French philosopher Jean Baudrillard (1929-2007) noted that we post-industrial moderns inhabit a world created of constant and pervasive imagery, what he termed ‘hyperreality’. Baudrillard claimed that this hyperreality has reversed the relationship of image and reality: images now precede and shape reality as opposed to reflecting a prior reality. The image creates the reality; hence, the rise of the absurd phenomenon of internet “influencers” and other moronic Gen-X agit-prop airbrushing the real. No wonder kids are mainlining heroin, jumping off buildings and shooting up schools. Their ‘reality’ is an incoherent, fucked-up mess of false perfection, self-aggrandizement and consumerism.

Our experience of the world is filtered through preconceptions and expectations that are products of media culture. As John Divola notes in Continuity (1997), the images we see offer a representational ground on which we base our sense of reality, “the millions of such images seen in a lifetime form the internal visual index of what we accept to be real.” In a world saturated with reproductions, representations, and imitations, it becomes very difficult to conceptualize a ‘pure reality’ to which we can contrast the myriad of simulated realities we create out of image environment we’re imprisoned in. Simulations have transformed modernity’s conception of what is real, in our behavior, our bodies, our buildings, our procedures, and our environment. The arrow between the real and the image has been reversed: now ‘reality’ is an effect of images, rather than images springing from something prior to and deeper. Instead of art imitating life, life now imitates art.