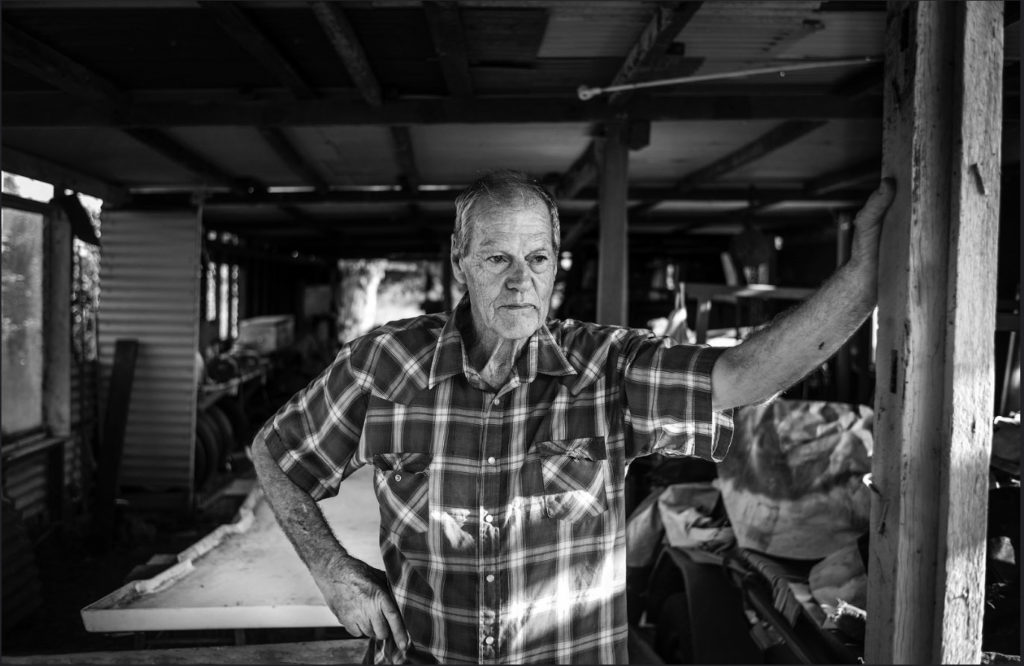

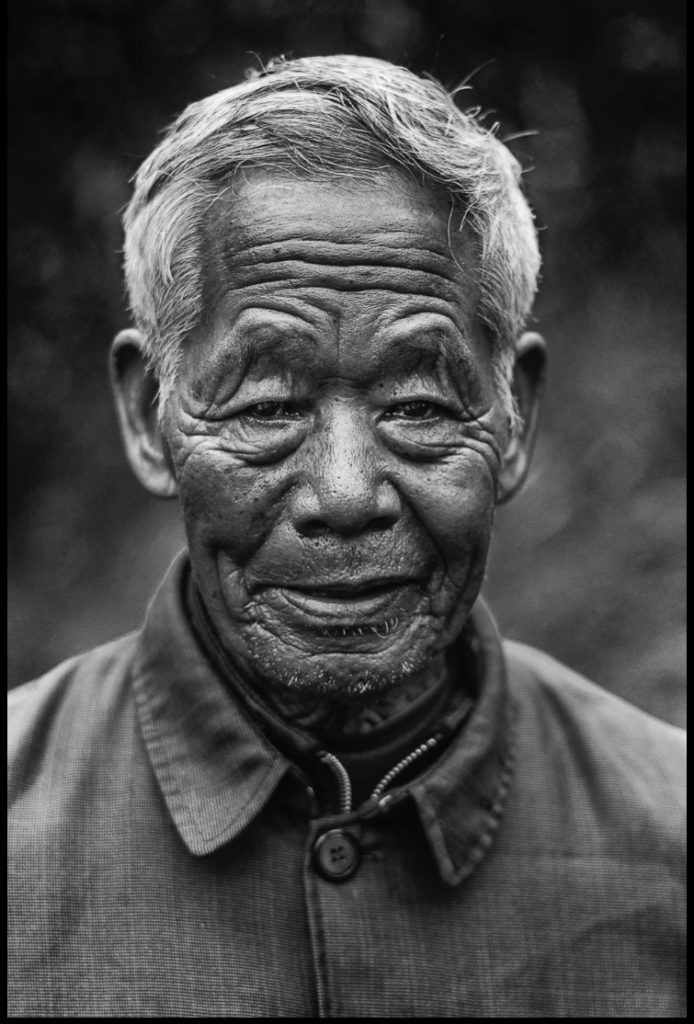

Peter Davidson is a former commercial photographer who now shoots for himself with a “hopelessly outdated” M9. The photos are all Mr. Davidson’s

Here are two cameras, both important, but separated by twenty years. The Kodak Brownie 127 and Leica M6. Each a delight to hold, simple to use and each delivering that photographic experience as a photographer, I relish. The opportunity to capture some fleeting quintessential moment that not only speaks to and for me, but to others. Personally, there is no argument as to which camera was the more valuable. The Brownie of course. And not just because that Brownie was my first camera back in 1965 and the M6 merely my first Leica in 1985. No, it was because the Brownie’s simplicity enabled me to see while not thinking (or indeed knowing) how to capture that what I saw. It just worked. And basically any camera that works well, and I don’t just mean in the mechanical sense, is essentially a means to an end. They are tools. So is this strange phenomenon of Leicaphilia a love of photography or of the tool? What is going on?

As I’m typing this, my nine year old and hence positively prehistoric and ancient (for digital) M9 is balefully staring back at me with its even older (25 years old in fact) Summicron IV single eye. Alongside is standing my equally old 90mm Tele-Elmarit with its fine coating of lens-fungus that gives results in a kind of cut-price Thambar way. All are in beautiful mint condition (apart from some fungus of course, but that is nothing). I look after my cameras. They are my tools and I trust that if I look after them, they will look after me. I shake my head at the wannabe war photographers who love to own a brassed and abused camera because of its ‘patina’. If it was previously owned by HCB, ok. If not, no thanks.

I’ve been a working advertising cum editorial professional photographer since 1971. That means, though still spritely for a man now pushing seventy years old with two major heart attacks under his belt, my eyes are not what they were. Nor are many other things. And I’m retired. All of which means I now photograph for myself and no one else.

So to return to my opening paragraph and the M6. I didn’t know any professional colleagues in my photographic field who owned a Leica back in the day. It wasn’t really the right tool for most jobs. Or any job really. It was full frame, in 21st Century speak, and as such technically limited. The Hasselblad was much bigger and hence better technical tool. As was 4×5 film and 8×10 film. The same rule applies today of course. For 35mm, or full frame if you prefer, the SLR ruled as it still does, but that is now changing. Basically, what I’m imperfectly trying to say, is that I was a TTL man through and through. The rangefinder was alien…

With my Nikon I could see exactly what I was shooting and focus quickly anywhere in the frame and could change a film roll almost one handed in the dark. The M6 was non of those things. What it was though, was a beautiful mechanical thing. A gorgeously built icon of photography. So, finding myself with some money to spare, I bought one. And found it so slow and difficult to use it drove me mad. It didn’t suit my photographic style. So I put it away for over twenty years, bringing it out occasionally to try and master the damned thing. Gradually, very gradually, it began to grow on me as my shooting style changed and I warmed to the experience. I realised, as I had long suspected, the camera wasn’t at fault, the fault lay with me.

I discovered I only needed to return to the Kodak Brownie state. Shoot don’t think. Relax. Let the camera do the work. Trust in the camera. Finally I began to fully appreciate the quiet unobtrusiveness of the small lens/camera form factor. Less intimidating for my subjects, being humble and quiet and therefor better. After nearly forty years as a photographer, I began to ‘get it’. So, of course, I sold my M6…

And bought an M9. Why? Because while I appreciate film, it’s a total pain in the arse. All my life I’ve battled Kodachrome exposure intolerance and while I loved Tri-X granularity, the whole film processing snafus, dust, scratches and water marks I can do without. And while I loved splashing about in darkrooms for hours, frankly I haven’t got many hours left.

The M9 is a flawed camera and hopelessly outdated. On paper. However, it’s secretly a film camera. That’s because it’s limitations are clear and to get the best from the camera you must work within its limitations and not in spite of them. Then it rewards you handsomely. And really, isn’t that the basis of the whole analogue resurgence? And it’s monochrome output, if the ISO is kept below 800, is to my mind the digital equivalent of Tri-X. You see, I know what this camera does. When I pick it up I know, for instance, that I will not have pressed some obscure button and accidental changed the shooting mode. Everything is simply laid out, visible and accessible. It works. It doesn’t get in the way. I don’t have to spend hours prodding menu buttons to make it do what I want. So of course I’m thinking of selling it…

Mainly because I’m finding it ever harder to focus manually. But what to get? I’ve checked out the small compact competition and they are fine, with quick auto focusing and comparatively very cheap but compromised either by ergonomics, sensor size or physical lens size. The thing is, on the M9 the 35mm Summicron lens is tiny. Really, really tiny. The Q by comparison has a huge ugly lens on its front. And it’s too wide at 28mm. And it’s fixed. I’m not convinced enough yet to part with my beloved M9. And if I do, it might have to be another Leica. Beloved? Did I use the term ‘beloved?’ Oh dear, have I contracted the strangely communicable disease of Leicaphilia? As I said earlier at the beginning of this piece, what is going on? Or as our yoof might text, WTF?

Yes, I am more attached to this camera than I am to my other long held and venerable cameras. The M9 welcomes my hand, feels right, comfortable and reassuringly solid and dependable. As do my Nikons of course… But they, in the end, are more tools for technical photographic challenges, while the M9 is more a tool for the heart, for expressiveness and intimacy. For capturing the human experience. It facilitates creating photography of meaning. So of course, as with any favourite craftsman’s tool, it also captures the heart of the photographer. How could it not?