By Anthony Lane, New Yorker Magazine, September 24, 2007

Fifty miles north of Frankfurt lies the small German town of Solms. Turn off the main thoroughfare and you find yourself driving down tranquil suburban streets, with detached houses set back from the road, and, on a warm morning in late August, not a soul in sight. By the time you reach Oskar-Barnack-Strasse, the town has almost petered out; just before the railway line, however, there is a clutch of industrial buildings, with a red dot on the sign outside. As far as fanfare is concerned, that’s about it. But here is the place to go, if you want to find the most beautiful mechanical objects in the world.

There have been Leica cameras since 1925, when the Leica I was introduced at a trade fair in Leipzig. From then on, as the camera has evolved over eight decades, generations of users have turned to it in their hour of need, or their millisecond of inspiration. Aleksandr Rodchenko, André Kertész, Walker Evans, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa, Robert Frank, William Klein, Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander, and Sebastião Salgado: these are some of the major-league names that are associated with the Leica brand—or, in the case of Cartier-Bresson, stuck to it with everlasting glue.

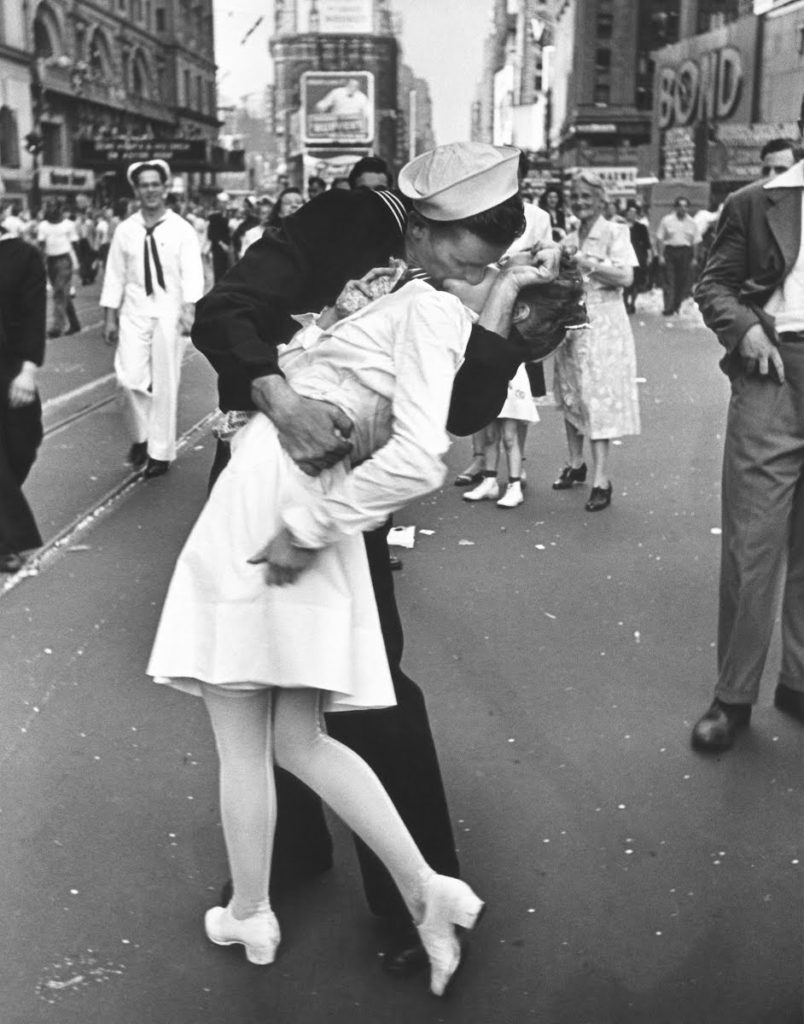

Even if you don’t follow photography, your mind’s eye will still be full of Leica photographs. The famous head shot of Che Guevara, reproduced on millions of rebellious T-shirts and student walls: that was taken on a Leica with a portrait lens—a short telephoto of 90 mm.—by Alberto Díaz Gutiérrez, better known as Korda, in 1960. How about the pearl-gray smile-cum-kiss reflected in the wing mirror of a car, taken by Elliott Erwitt in 1955? Leica again, as is the even more celebrated smooch caught in Times Square on V-J Day, 1945—a sailor craned over a nurse, bending her backward, her hand raised against his chest in polite half-protestation. The man behind the camera was Alfred Eisenstaedt, of Life magazine, who recalled:

I was running ahead of him with my Leica, looking back over my shoulder. But none of the pictures that were possible pleased me. Then suddenly, in a flash, I saw something white being grabbed. I turned around and clicked.

He took four pictures, and that was that. “It was done within a few seconds,” he said. All you need to know about the Leica is present in those seconds. The photographer was on the run, so whatever he was carrying had to be light and trim enough not to be a drag. He swivelled and fired in one motion, like the Sundance Kid. And everything happened as quickly for him as it did for the startled nurse, with all the components—the angles, the surrounding throng, the shining white of her dress and the kisser’s cap—falling into position. Times Square was the arena of uncontrolled joy; the job of the artist was to bring it under control, and the task of his camera was to bring life—or, at least, an improved version of it, graced with order and impact—to the readers of Life.

*************

Still, why should one lump of metal and glass be better at fulfilling that duty than any other? Would Eisenstaedt really have been worse off, or failed to hit the target, with another sort of camera? These days, Leica makes digital compacts and a beefy S.L.R., or single-lens reflex, called the R9, but for more than fifty years the pride of the company has been the M series of 35-mm. range-finder cameras—durable, companionable, costly, and basically unchanging, like a spouse. There are three current models, one of which, the MP, will set you back a throat-drying four thousand dollars or so; having stood outside dustless factory rooms, in Solms, and watched women in white coats and protective hairnets carefully applying black paint, with a slender brush, to the rim of every lens, I can tell you exactly where your money goes. Mind you, for four grand you don’t even get a lens—just the MP body. It sits there like a gum without a tooth until you add a lens, the cheapest being available for just under a thousand dollars. (Five and a half thousand will buy you a 50-mm. f/1, the widest lens on the market; for anybody wanting to shoot pictures by candlelight, there’s your answer.) If you simply want to take a nice photograph of your children, though, what’s wrong with a Canon PowerShot? Yours online for just over two hundred bucks, the PowerShot SD1000 will also zoom, focus for you, set the exposure for you, and advance the frame automatically for you, none of which the MP, like some sniffing aristocrat, will deign to do. To make the contest even starker, the SD1000 is a digital camera, fizzing with megapixels, whereas the Leica still stores images on that frail, combustible material known as film. Short of telling the kids to hold still while you copy them onto parchment, how much further out of touch could you be?

To non-photographers, Leica, more than any other manufacturer, is a legend with a hint of scam: suckers paying through the nose for a name, in a doomed attempt to crank up the credibility of a picture they were going to take anyway, just as weekend golfers splash out on a Callaway Big Bertha in a bid to convince themselves that, with a little more whippiness in their shaft, they will swell into Tiger Woods. To unrepentant aesthetes, on the other hand, there is something demeaning in the idea of Leica. Talent will out, they say, whatever the tools that lie to hand, and in a sense they are right: Woods would destroy us with a single rusty five-iron found at the back of a garage, and Cartier-Bresson could have picked up a Box Brownie and done more with a roll of film—summoning his usual miracles of poise and surprise—than the rest of us would manage with a lifetime of Leicas. Yet the man himself was quite clear on the matter:

I have never abandoned the Leica, anything different that I have tried has always brought me back to it. I am not saying this is the case for others. But as far as I am concerned it is the camera. It literally constitutes the optical extension of my eye.

Asked how he thought of the Leica, Cartier-Bresson said that it felt like “a big warm kiss, like a shot from a revolver, and like the psychoanalyst’s couch.” At this point, five thousand dollars begins to look like a bargain.

*************

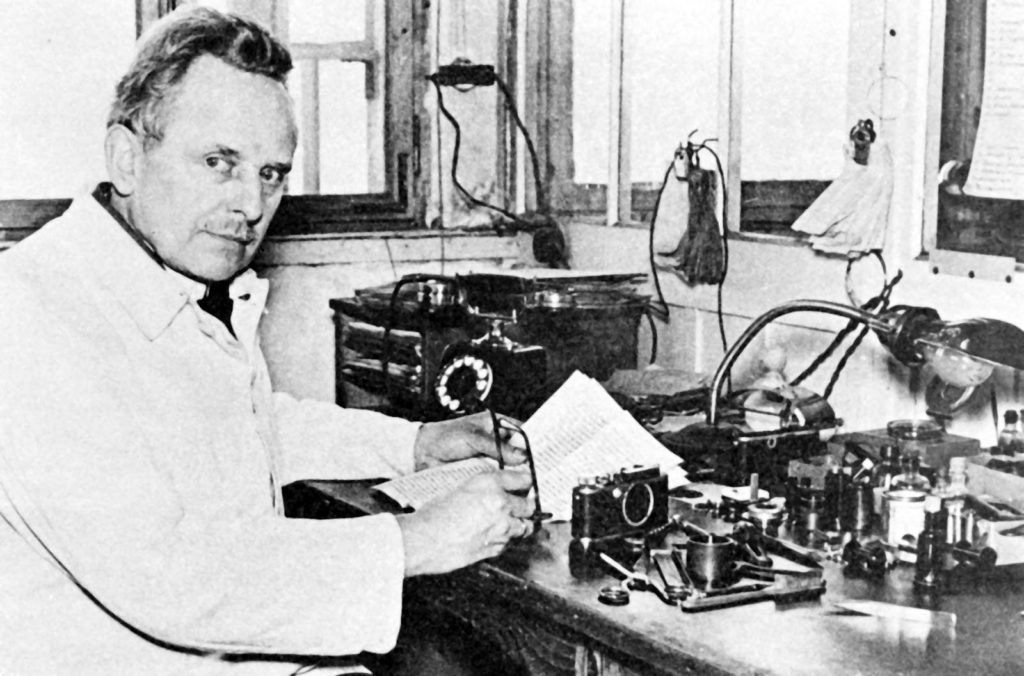

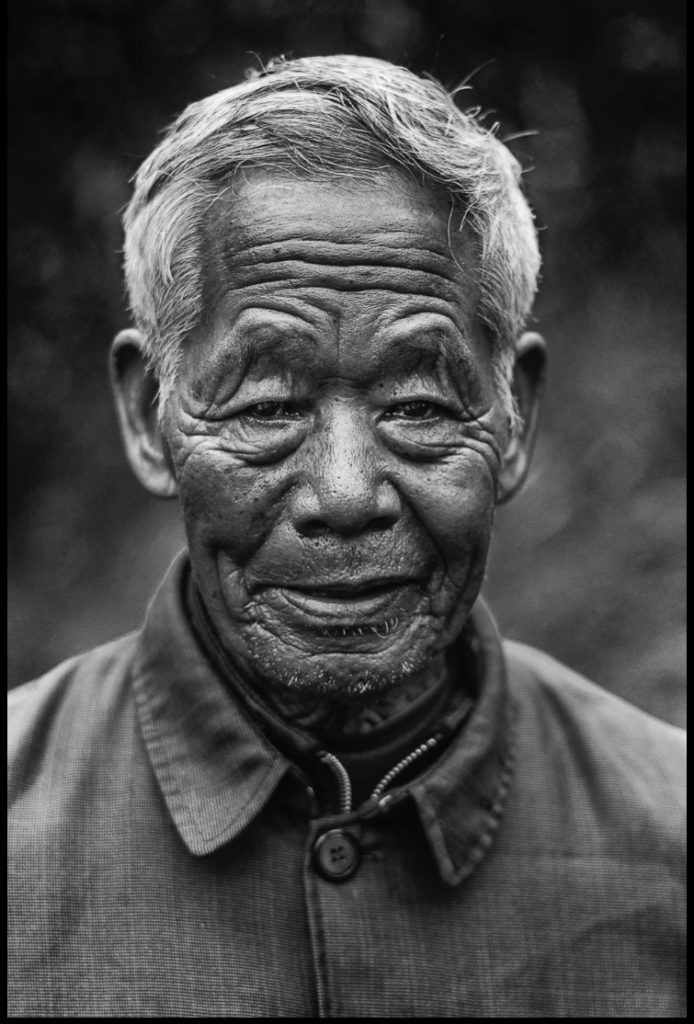

Oscar Barnack at his Desk

Many reasons have been adduced for the rise of the Leica. There is the hectic progress of the illustrated press, avid for photographs to fill its columns; there is the increased mobility, spending power, and leisure time of the middle classes, who wished to preserve a record of these novel blessings, if not for posterity, then at least for show. Yet the great inventions, more often than not, are triggered less by vast historical movements than by the pressures of individual chance—or, in Leica’s case, by asthma. Every Leica employee who drives down Oskar-Barnack-Strasse is reminded of corporate glory, for it was Barnack, a former engineer at Carl Zeiss, the famous lens-makers in Jena, who designed the Leica I. He was an amateur photographer, and the camera had first occurred to him, as if in a vision, in 1905, twenty years before it actually went on sale:

Back then I took pictures using a camera that took 13 by 18 plates, with six double-plate holders and a large leather case similar to a salesman’s sample case. This was quite a load to haul around when I set off each Sunday through the Thüringer Wald. While I struggled up the hillsides (bearing in mind that I suffer from asthma) an idea came to me. Couldn’t this be done differently?

Five years later, Barnack was invited to work for Ernst Leitz, a rival optical company, in Wetzlar. (The company stayed there until 1988, when it was sold, and the camera division, renamed Leica, shifted to Solms, fifteen minutes away.) By 1913-14, he had developed what became known as the ur-Leica: a tough, squat rectangular metal box, not much bigger than a spectacles case, with rounded corners and a retractable brass lens. You could tuck it into a jacket pocket, wander around the Thuringer woods all weekend, and never gasp for breath. The extraordinary fact is that, if you were to place it next to today’s Leica MP, the similarities would far outweigh the differences; stand a young man beside his own great-grandfather and you get the same effect.

Barnack took a picture on August 2, 1914, using his new device. Reproduced in Alessandro Pasi’s comprehensive study, “Leica: Witness to a Century” (2004), it shows a helmeted soldier turning away from a column on which he has just plastered the imperial order for mobilization. This was the first hint of the role that would fall to Leicas above all other cameras: to be there in history’s face. Not until the end of hostilities did Barnack resume work on the Leica, as it came to be called. (His own choice of name was Lilliput, but wiser counsels prevailed.) Whenever you buy a 35-mm. camera, you pay homage to Barnack, for it was his handheld invention that popularized the 24-mm.-by-36-mm. negative—a perfect ratio of 2:3—adapted from cine film. According to company lore, he held a strip of the new film between his hands and stretched his arms wide, the resulting length being just enough to contain thirty-six frames—the standard number of images, ever since, on a roll of 35-mm. film. Well, maybe. Does this mean that, if Barnack had been more of an ape, we might have got forty?

*************

When the Leica I made its eventual début, in 1925, it caused consternation. In the words of one Leica historian, quoted by Pasi, “To many of the old photographers it looked like a toy designed for a lady’s handbag.” Over the next seven years, however, nearly sixty thousand Leica I’s were sold. That’s a lot of handbags. The shutter speeds on the new camera ran up to one five-hundredth of a second, and the aperture opened wide to f/3.5. In 1932, the Leica II arrived, equipped with a range finder for more accurate focussing. I used one the other day—a mid-thirties model, although production lasted until 1948. Everything still ran sweetly, including the knurled knob with which you wind on from frame to frame, and the simplicity of the design made the Leica an infinitely more friendly proposition, for the novice, than one of the digital monsters from Nikon and Canon. Those need an instruction manual only slightly smaller than the Old Testament, whereas the Leica II sat in my palms like a puppy, begging to be taken out on the streets.

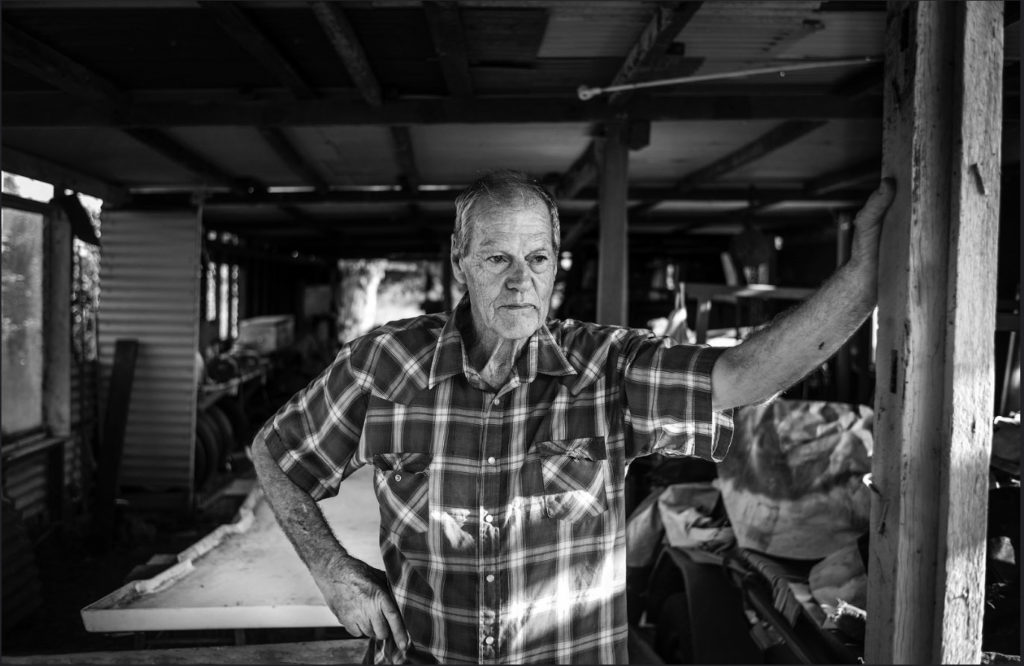

That is how it struck not only the public but also those for whom photography was a living, or an ecstatic pursuit. A German named Paul Wolff acquired a Leica in 1926 and became a high priest to the brand, winning many converts with his 1934 book “My Experiences with the Leica.” His compatriot Ilsa Bing, born to a Jewish family in Frankfurt, was dubbed “the Queen of the Leica” after an exhibit in 1931. She had bought the camera in 1929, and what is remarkable, as one scrolls through a roster of her peers, is how quickly, and infectiously, the Leica habit caught on. Whenever I pick up a book of photographs, I check the chronology at the back. From a monograph by the Hungarian André Kertész, the most wistful and tactful of photographers: “1928—Purchases first Leica.” From the catalogue of the 1998 Aleksandr Rodchenko show at moma: “1928, November 25—Stepanova’s diary records Rodchenko’s purchase of a Leica for 350 rubles.” And on it goes.

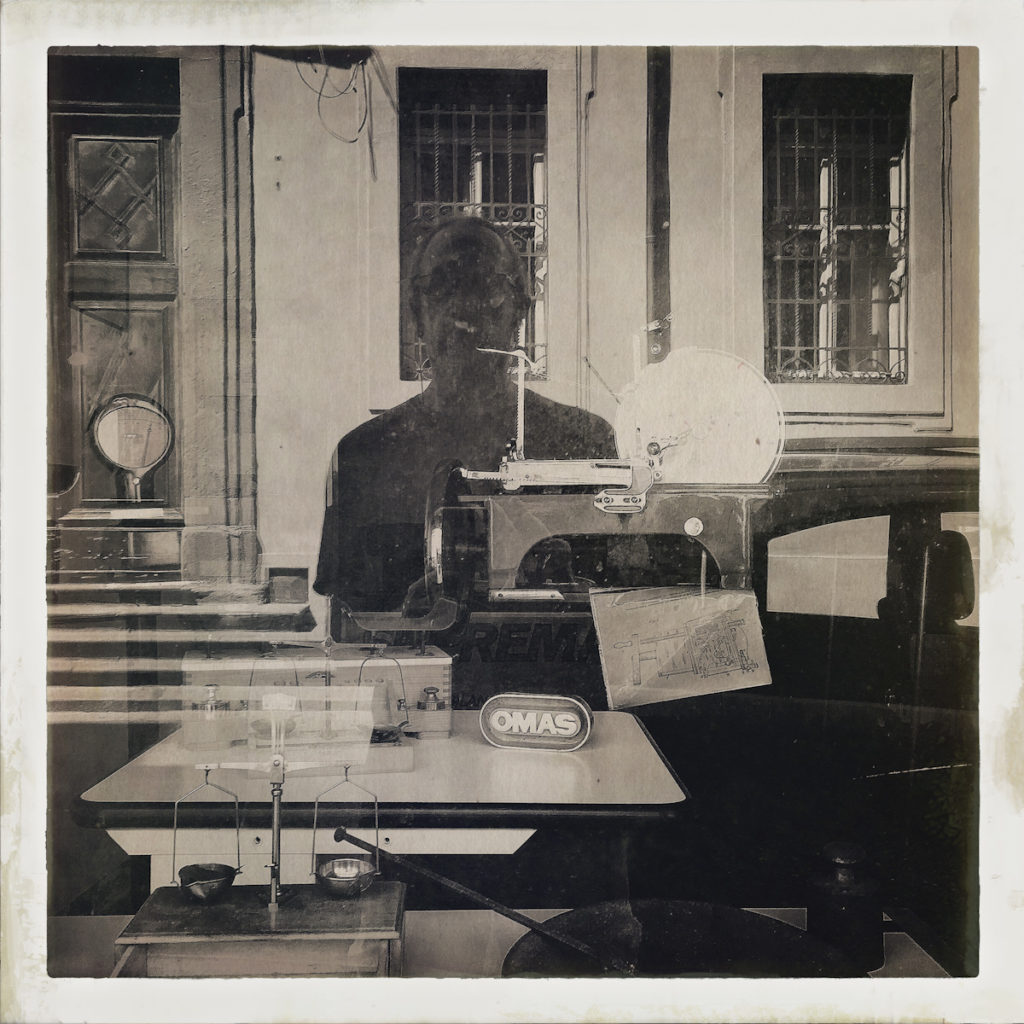

Ilsa Bing

The Russians were among the first and fiercest devotees, and anyone who craves the Leica as a pure emblem of capitalist desire—what Marx would call commodity fetishism—may also like to reflect on its status, to men like Rodchenko, as a weapon in the revolutionary struggle. Never a man to be tied down (he was also a painter, sculptor, and master of collage), he nonetheless believed that “only the camera is capable of reflecting contemporary life,” and he went on the attack, craning up at buildings and down from roofs, tipping his Leica at flights of steps and street parades, upending the world as if all its old complacencies could be shaken out of the bottom like dust. There is a gorgeous shot from 1934 entitled “Girl with a Leica,” in which his subject perches politely on a bench that arrows diagonally, and most impolitely, from lower left to upper right. She wears a soft white beret and dress, and her gaze is blank and misty, but thrown over the scene, like a net, is the shadow of a window grille—modernist geometry at war with reactionary decorum. The object she clasps in her lap, its strap drawn tightly over her shoulder, is of the same make as the one that created the picture.

When it came to off-centeredness, Rodchenko’s fellow-Russian Ilya Ehrenburg went one better. “A camera is clumsy and crude. It meddles insolently in other people’s affairs,” he wrote in 1932. “Ours is a guileful age. Following man’s example, things have also learned to dissemble. For many months I roamed Paris with a little camera. People would sometimes wonder: why was I taking pictures of a fence or a road? They didn’t know that I was taking pictures of them.” Ehrenburg had solved the problem of meddling by buying an accessory: “The Leica has a lateral viewfinder. It’s constructed like a periscope. I was photographing at 90 degrees.” The Paris that emerged—poor, grimy, and unposed—was a moral rebuke to the myth of bohemian chic.

*************

You can still buy a right-angled viewfinder for a new Leica, if you’re too shy or sneaky to confront your subjects head-on, although the basic thrust of Leica technique has been to insist that no extra subterfuge is required: the camera can hide itself. If I had to fix the source of that reticence, I would point to Marseilles in 1932. It was then that Cartier-Bresson, an aimless young Frenchman from a wealthy family, bought his first Leica. He proceeded to grow into the best-known photographer of the twentieth century, in spite (or, as he would argue, because) of his ability to walk down a street not merely unrecognized but unnoticed. He began as a painter, and continued to draw throughout his life, but his hand was most comfortable with a camera.

When I spoke to his widow, Martine Franck—the president of the Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation, in Paris, and herself a distinguished photographer—she said that her husband in action with his Leica “was like a dancer.” This feline unobtrusiveness led him all over the world and made him seem at home wherever he paused; one trip to Asia lasted three years, ending in 1950, and produced eight hundred and fifty rolls of film. His breakthrough collection, published two years later, was called “The Decisive Moment,” and he sought endless analogies for the sensation that was engendered by the press of a shutter. The most common of these was hunting: “The photographer must lie in wait, watching out for his prey, and have a presentiment of what is about to happen.”

There, if anywhere, is the Leica motto: watch and wait. If you were a predator, the moment—not just for Cartier-Bresson, but for all photographers—became that much more decisive in 1954. “Clairvoyance” means “clear sight,” and when Leica launched the M3 that year, the clarity was a coup de foudre; even now, when you look through a used M3, the world before you is brighter and crisper than seems feasible. You half expect to feel the crunch of autumn leaves beneath your feet. A Leica viewfinder resembles no other, because of the frame lines: thin white strips, parallel to each side of the frame, which show you the borders of the photograph that you are set to take—not merely the lie of the land within the shot, but also what is happening, or about to happen, just outside. This is a matter of millimetres, but to Leica fans it is sacred, because it allows them to plan and imagine a photograph as an act of storytelling—an instant grabbed at will from a continuum. If you want a slice of life, why not see the loaf?

*************

The M3 had everything, although by the standards of today it had practically nothing. You focussed manually, of course, and there was nothing to help you calculate the exposure; either you carried a separate light meter, or you clipped one awkwardly to the top of the camera, or, if you were cool, you guessed. Cartier-Bresson was cool. Martine Franck is still cool: “I think I know my light by now,” she told me. She continues to use her M3: “I’ve never held a camera so beautiful. It fits the hand so well.” Even for people who know nothing of Cartier-Bresson, and for whom 1954 is as long ago as Pompeii, something about the M3 clicks into place: last year, when eBay and Stuff magazine, in the U.K., took it upon themselves to nominate “the top gadget of all time,” the Game Boy came fifth, the Sony Walkman third, and the iPod second. First place went to an old camera that doesn’t even need a battery. If the Queen subscribes to Stuff, she will have nodded in approval, having owned an M3 since 1958. Her Majesty is so wedded to her Leica that she was once shown on a postage stamp holding it at the ready.

It’s no insult to call the M3 a gadget. Such beauty as it possesses flows from its scorn for the superfluous; as any Bauhaus designer could tell you, form follows function. The M series is the backbone of Leica; we are now at the M8 (which at first glance is barely distinguishable from the M3), and, with a couple of exceptions, every intervening camera has been a classic. Richard Kalvar, who rose to become president of the Magnum photographic agency during the nineties, remembers hearing the words of a Leica fan: “I know I’m using the best, and I don’t have to think about it anymore.” Kalvar bought an M4 and never looked back: “It’s almost a part of me,” he says. Ralph Gibson, whose photographs offer an unblinking survey of the textures that surround us, from skin to stone, bought his first Leica, an M2 (which, confusingly, postdated the M3), in 1961. It cost him three hundred dollars, which, considering that he was earning a hundred a week, was quite an outlay, but his loyalty is undimmed. “More great photographs have been made with a Leica and a 50-mm. lens than with any other combination in the history of photography,” Gibson said to me. He advised Leica beginners to use nothing except that standard lens for two or three years, so as to ease themselves into the swing of the thing: “What you learn you can then apply to all the other lengths.

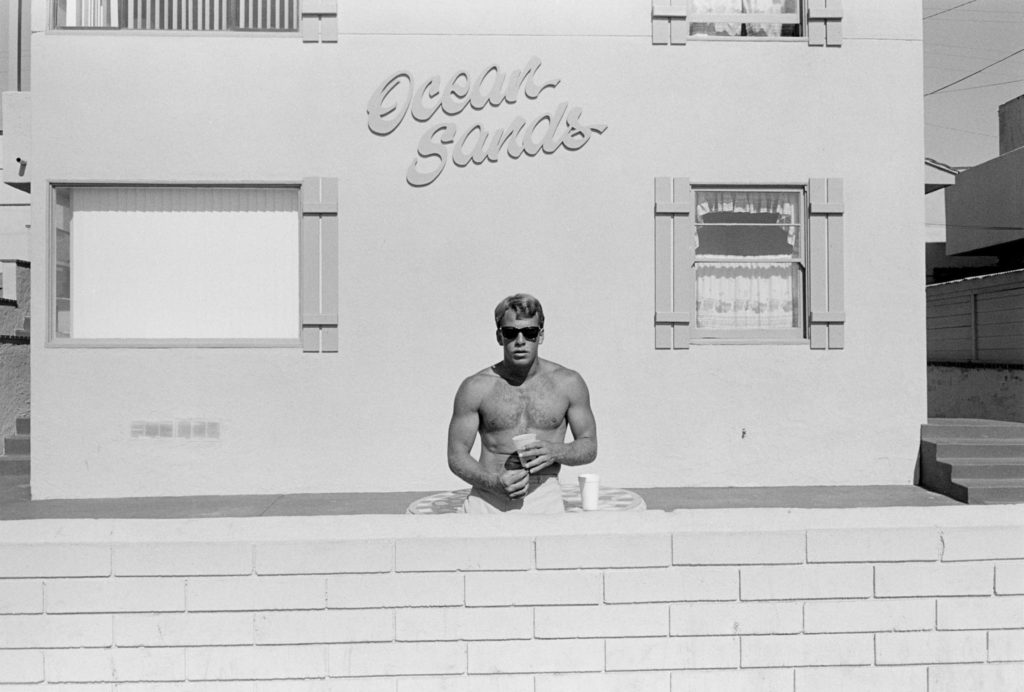

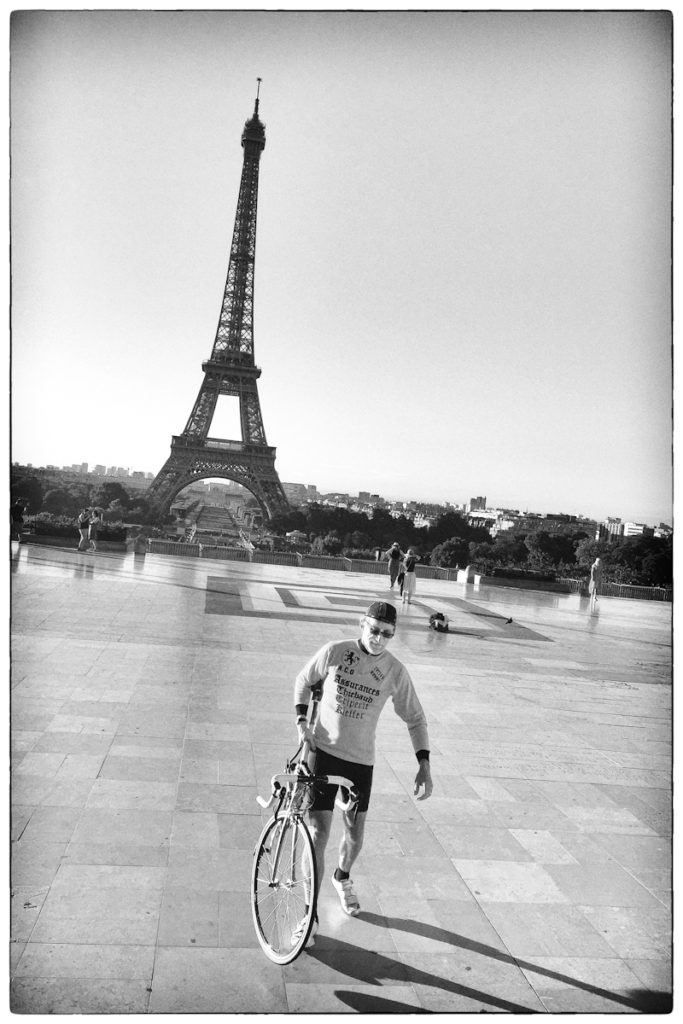

One could argue that, since the nineteen-fifties and sixties, the sense of Europe as the spiritual hearth of Leica, with the Paris of Kertész and Cartier-Bresson glowing at its core, has been complemented, if not superseded, by America’s attraction to the brand. The Russian love of the angular had exploited the camera’s portability (you try bending over a window ledge with a plate camera); the French had perfected the art of reportage, netting experience on the wing; but the Leicas that conquered America—the M3, the M4, and later the M6, with built-in metering and the round red Leica logo on the front—were wielded with fresh appetite, biting at the world and slicing it off in unexpected chunks. Lee Friedlander, photographing a child in New York, in 1963, thought nothing of bringing the camera down to the boy’s eye level, and thus semi-decapitating the grownups who stood beside him. (All kids dream of that sometime.) Men and women were reflected in storefront windows, or obscured by street signs; many of the photographs shimmered on the brink of a mistake. “With a camera like that,” Friedlander has said of the Leica, “you don’t believe that you’re in the masterpiece business. It’s enough to be able to peck at the world.” One shot of his, from 1969, traps an entire landscape of feeling—a boundless American sky, salted with high clouds, plus Friedlander’s wife, Maria, with her lightly smiling face—inside the cab of a single truck, layering what we see through the side window with what is reflected in it. I know of long novels that tell you less.

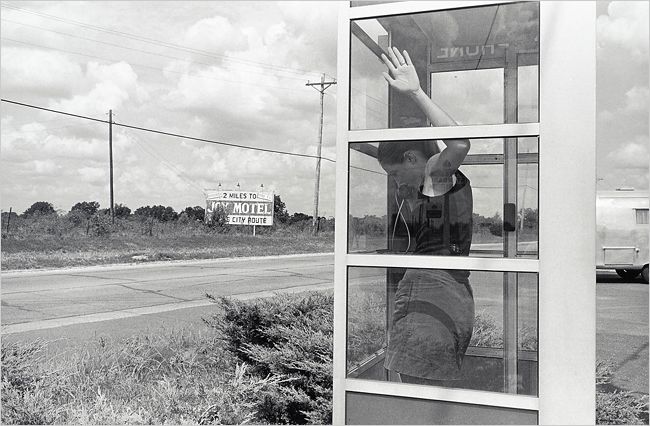

Before Friedlander came Robert Frank, born in Switzerland; only someone from a mountainous country, perhaps, could come here and view the United States as a flat and tragic plain. “The Americans” (1958), the record of his travels with a Leica, was mostly haze, shade, and grain, stacked with human features resigned to their fate. No artist had ever studied a men’s room in such detail before, with everything from the mop to the hand dryer immortalized in the wide embrace of the lens; Jack Kerouac, who wrote the introduction to the book, lauded the result, taken in Memphis, Tennessee, as “the loneliest picture ever made, the urinals that women never see, the shoeshine going on in sad eternity.” Then, there was Garry Winogrand, the least exhaustible of all photographers. Frank’s eighty-three images may have been chosen from five hundred rolls of film, but when Winogrand died, in 1984, at the age of fifty-six, he left behind more than two and a half thousand rolls of film that hadn’t even been developed. He leavened the wistfulness of Frank with a documentary bluntness and a grinning wit, incessantly tilting his Leica to throw a scene off-balance and seek a new dynamic. His picture of a disabled man in Los Angeles, in 1969, could have been fuelled by pathos alone, or by political rage at an indifferent society, but Winogrand cannot stop tracking that society in its comic range; that is why we get not just the wheelchair and the begging bowl but also a trio of short-skirted girls, bunched together like a backup group, strolling through the Vs of shadow and sunlight, and a portly matron planted at the right of the frame—a stolid import from another age.

*************

Garry Winogrand’s M4

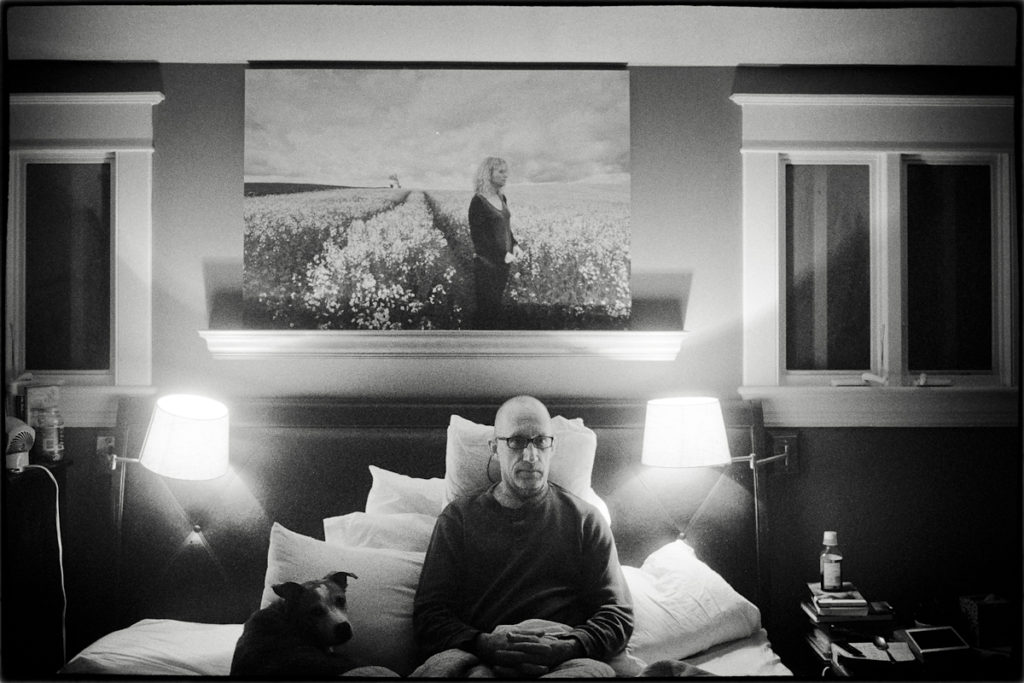

I recently found a picture of Winogrand’s M4. The metal is not just rubbed but visibly worn down beside the wind-on lever; you have to shoot a heck of a lot of photographs on a Leica before that happens. Still, his M4 is in mint condition compared with the M2 owned by Bruce Davidson, the American photographer whose work constitutes, among other things, an invaluable record of the civil-rights movement. And even his M2, pitted and peeled like the bark of a tree, is pristine compared with the Leica I saw in the display case at the Leica factory in Solms. That model had been in the Hindenburg when it went up in flames in New Jersey in 1937. The heat was so intense that the front of the lenses melted. So now you know: Leica engineers test their product to the limits, and they will customize it for you if you are planning a trip to the Arctic, but when you really want to trash your precious camera you need an exploding airship.

If you pick up an M-series Leica, two things are immediately apparent. First, the density: the object sits neatly but not lightly in the hand, and a full day’s shooting, with the camera continually hefted to the eye, leaves you with a faint but discernible case of wrist ache. Second, there is no lump. Most of the smarter, costlier cameras in the world are S.L.R.s, with a lumpy prism on top. Light enters through the lens, strikes an angled mirror, and bounces upward to the prism, where it strikes one surface after another, like a ball in a squash court, before exiting through the viewfinder. You see what your lens sees, and you focus accordingly. This happy state of affairs does not endure. As you take a picture, the mirror flips up out of the light path. The image, now unobstructed, reaches straight to the rear of the camera and, as the shutter opens, burns into the emulsion of the film—or, these days, registers on a digital sensor. With every flip, however, comes a flip side: the mirror shuts off access to the prism, meaning that, at the instant of release, your vision is blocked, and you are left gazing at the dark.

To most of us, this is not a problem. The instant passes, the mirror flips back down, and lo, there is light. For some photographers, though, the impediment is agony: of all the times to deny us the right to look at our subject, S.L.R.s have to pick this one? “Visualus interruptus,” Ralph Gibson calls it, and here is where the Leica M series plays its ace. The Leica is lumpless, with a flat top built from a single piece of brass. It has no prism, because it focusses with a range finder—situated above the lens. And it has no mirror inside, and therefore no clunk as the mirror swings. When you take a picture with an S.L.R., there is a distinctive sound, somewhere between a clatter and a thump; I worship my beat-up Nikon FE, but there is no denying that every snap reminds me of a cow kicking over a milk pail. With a Leica, all you hear is the shutter, which is the quietest on the market. The result—and this may be the most seductive reason for the Leica cult—is that a photograph sounds like a kiss.

From the start, this tinge of diplomatic subtlety has shaded our view of the Leica, not always helpfully. The M-series range finder feels made for the finesse and formality of black-and-white—yet consider the oeuvre of William Eggleston, whose unabashed use of color has delivered, through Leica lenses, a lesson in everyday American surrealism, which, like David Lynch movies, blooms almost painfully bright. Again, the Leica, with its range of wide-aperture lenses, is the camera for natural light, and thus inimical to flash, yet Lee Friedlander conjured a series of plainly flashlit nudes, in the nineteen-seventies, which finds tenderness and dignity in the brazen. Lastly, a Leica is, before anything else, a 35-mm. camera. Barnack shaped the Leica I around a strip of film, and the essential mission of the brand since then has been to guarantee that a single chemical event—the action of light on a photosensitive surface—passes off as smoothly as possible. Picture the scene, then, in Cologne, in the fall of 2006. At Photokina, the biennial fair of the world’s photographic trade, Leica made an announcement: it was time, we were told, for the M8. The M series was going digital. It was like Dylan going electric.

In a way, this had to happen. The tide of our lives is surging in a digital direction. My complete childhood is distilled into a couple of photograph albums, with the highlights, whether of achievement or embarrassment, captured in no more than a dozen talismanic stills, now faded and curling at the edges. Yet our own children go on one school trip and return with a hundred images stashed on a memory card: will that enhance or dilute their later remembrance of themselves? Will our experience be any the richer for being so retrievable, or could an individual history risk being wiped, or corrupted, as briskly as a memory card? Garry Winogrand might have felt relieved to secure those thousands of images on a hard drive, rather than on frangible film, although it could be that the taking of a photograph meant more to him than the printed result. The jury is out, but one thing is for sure: film is dwindling into a minority taste, upheld largely by professionals and stubborn, nostalgic perfectionists. Nikon now offers twenty-two digital models, for instance, while the “wide array of SLR film cameras,” as promised on its Web site, numbers precisely two.

Lee knows what is at stake, being a Leica-lover of long standing. Asked about the difference between using his product and an ordinary camera, he replied: “One is driving a Morgan four-by-four down a country lane, the other one is getting in a Mercedes station wagon and going a hundred miles an hour.” The problem is that, for photographers as for drivers, the most pressing criterion these days is speed, and anything more sluggish than the latest Mercedes—anything, likewise, not tricked out with luxurious extras—belongs to the realm of heritage. There is an astonishing industry in used Leicas, with clubs and forums debating such vital areas of contention as the strap lugs introduced in 1933. There are collectors who buy a Leica and never take it out of the box; others who discreetly amass the special models forged for the Luftwaffe. Ralph Gibson once went to a meeting of the Leica Historical Society of America and, he claims, listened to a retired Marine Corps general give a scholarly paper on certain discrepancies in the serial numbers of Leica lens caps. “Leicaweenies,” Gibson calls such addicts, and they are part of the charming, unbreakable spell that the name continues to cast, as well as a tribute to the working longevity of the cameras. By an unfortunate irony, the abiding virtues of the secondhand slow down the sales of the new: why buy an M8 when you can buy an M3 for a quarter of the price and wind up with comparable results? The economic equation is perverse: “I believe that for every euro we make in sales, the market does four euros of business,” Lee said.

*************

I have always wanted a Leica, ever since I saw an Edward Weston photograph of Henry Fonda, his noble profile etched against the sky, a cigarette between two fingers, and a Leica resting against the corduroy of his jacket. I have used a variety of cultish cameras, all of them secondhand at least, and all based on a negative larger than 35 mm.: a Bronica, a Mamiya 7, and the celebrated twin-lens Rolleiflex, which needs to be cupped at waist height. (“If the good Lord had wanted us to take photographs with a 6 by 6, he would have put eyes in our belly,” a scornful Cartier-Bresson said.) But I have never used a Leica. Now I own one: a small, dapper digital compact called the D-Lux 3. It has a fine lens, and its grace note is a retro leather case that makes me feel less like Henry Fonda and more like a hiker named Helmut, striding around the Black Forest in long socks and a dark-green hat with a feather in it; but a D-Lux 3 is not an M8. For one thing, it doesn’t have a proper viewfinder. For another, it costs close to six hundred dollars—the upper limit of my budget, but laughably cheap to anyone versed in the M series. So, to discover what I was missing, I rented an M8 and a 50-mm lens for four hours, from a Leica dealer, and went to work.

If you can conquer the slight queasiness that comes from walking about with seven thousand dollars’ worth of machinery hanging around your neck, an afternoon with the M8 is a dangerously pleasant groove to get into. I can understand that, were you a sports photographer, perched far away from the action, or a paparazzo, fighting to squeeze off twenty consecutive frames of Britney Spears falling down outside a night club, this would not be your tool of choice, but for more patient mortals it feels very usable indeed. This is not just a question of ergonomics, or of the diamond-like sharpness of the lens. Rather, it has to do with the old, bewildering Leica trick: the illusion, fostered by a mere machine, that the world out there is asking to be looked at—to be caught and consumed while it is fresh, like a trout. Ever since my teens, as one substandard print after another glimmered into view in the developing tray, under the brothel-red gloom of the darkroom, my own attempts at photography have meant a lurch of expectation and disappointment. Now, with an M8 in my possession, the shame gave way to a thrill. At one point, I stood outside a bookstore and, in a bid to test the exposure, focussed on a pair of browsers standing within, under an “Antiquarian” sign at the end of a long shelf. Suddenly, a pale blur entered the frame lines. I panicked, and pressed the shutter: kiss.

On the digital playback, I inspected the evidence. The blur had been an old lady, and she had emerged as a phantom—the complete antiquarian, with glowing white hair and a hint of spectacles. It wasn’t a good photograph, more of a still from “Ghostbusters,” but it was funnier and punchier than anything I had taken before, and I could only have grabbed it with a Leica. (And only with an M. By the time the D-Lux 3 had fired up and focussed, the lady would have floated halfway down the street.) So the rumors were true: buy this camera, and accidents will happen. I remembered what Cartier-Bresson once said about turning from painting to photography: “the adventurer in me felt obliged to testify with a quicker instrument than a brush to the scars of the world.” That is what links him to the Leicaweenies, and Oskar Barnack to the advent of the M8, and Russian revolutionaries to flashlit American nudes: the simple, undying wish to look at the scars.

Views: 195

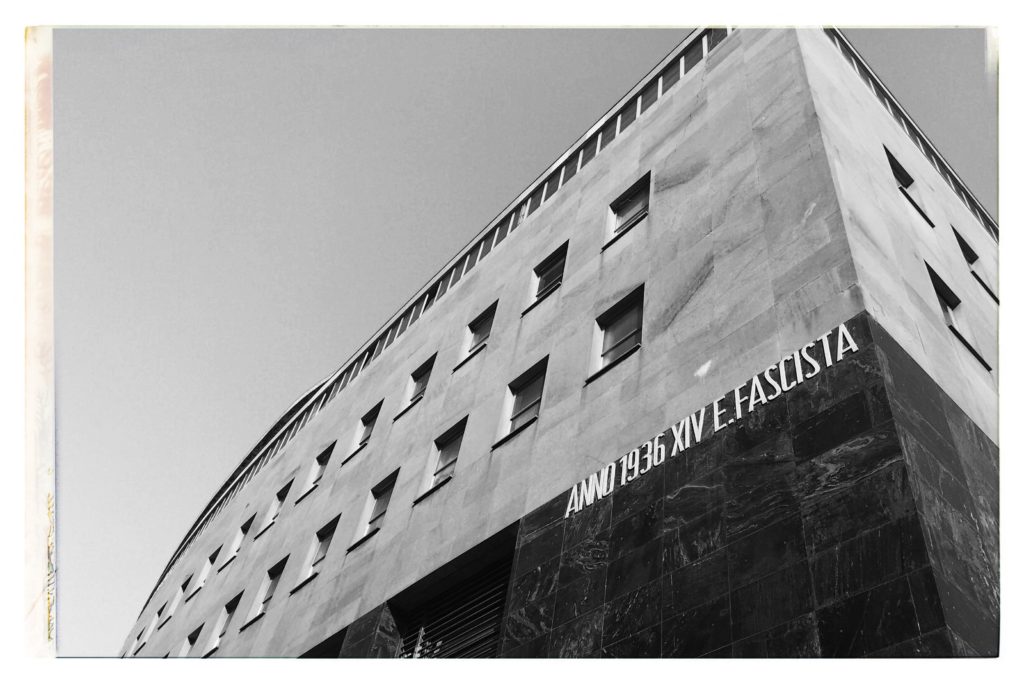

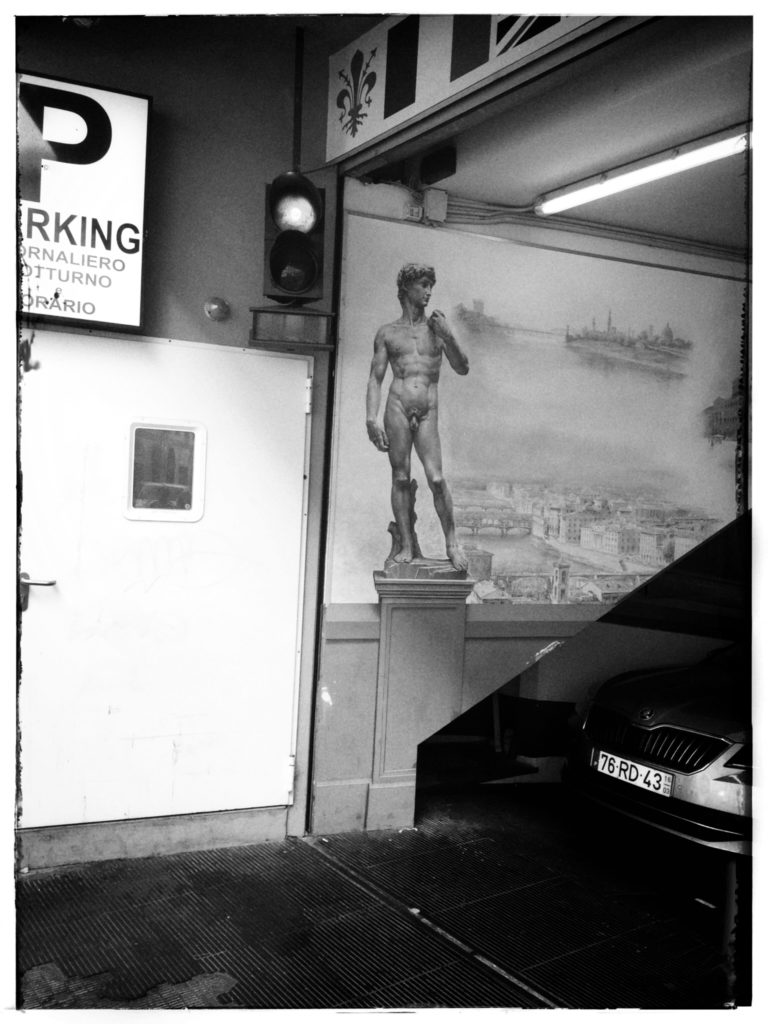

Florence

Florence