“Where is my home? It is indistinct as an old cellar hole, now a faint indentation, merely, in a farmer’s field. And I sit by the old site by the stump of an old oak that once grew there. Such is the nature of where we have lived.” Henry David Thoreau

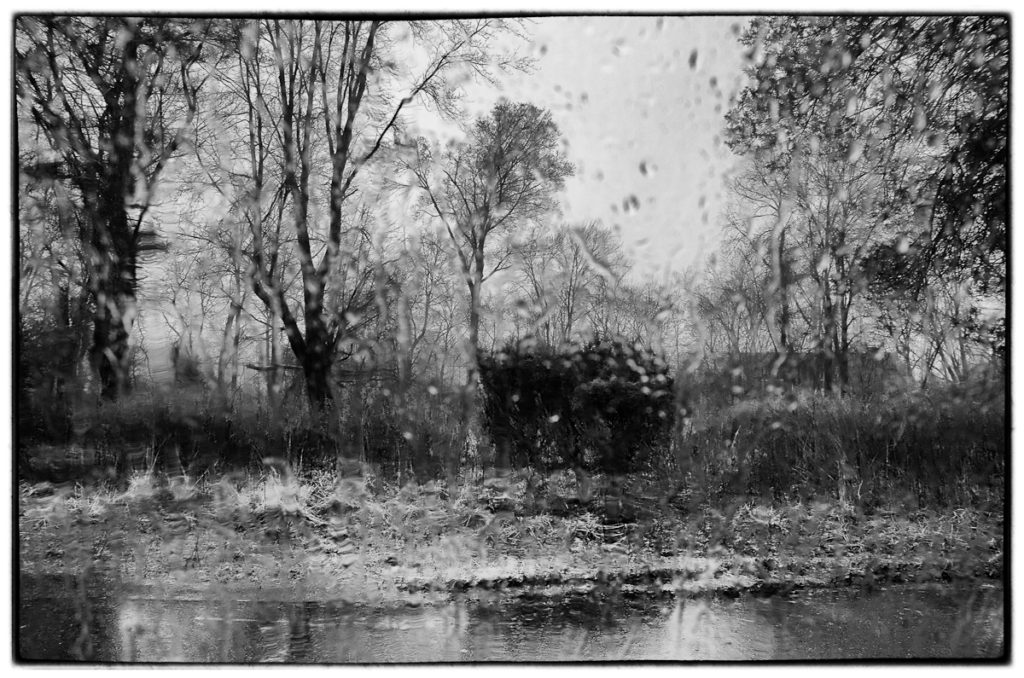

Above is a picture of what remains of 9 Grand St, Wayne, New Jersey. It’s now just a muddy patch of bog in a run-down working class neighborhood, mostly abandoned, prone to flooding by the Passaic River, which it backs up against. Back in the 70’s, when I lived there, it used to flood occasionally, but nothing like it does now, and most of the houses on the street, where people I knew lived, have either been torn down or are unoccupied, surrendered by owners who cashed out insurance claims, gave up and moved elsewhere.

I’d been in the area visiting my mother, age 80, who lives nearby, and decided to ride by and see the old neighborhood. The house is gone, though I recognize a few trees in the yard and can, with a bit of imagination, remember how it sat on the land. What’s interesting to me is how vivid my memories are of this place, in part because I lived here during a time in my life when I was young and healthy and had my whole adult life ahead of me. Having a number of amorous young women living within a stone’s throw of my bedroom window didn’t hurt either. I also had a camera, something I carried everywhere with me, so I documented much of the life I then lived.

*************

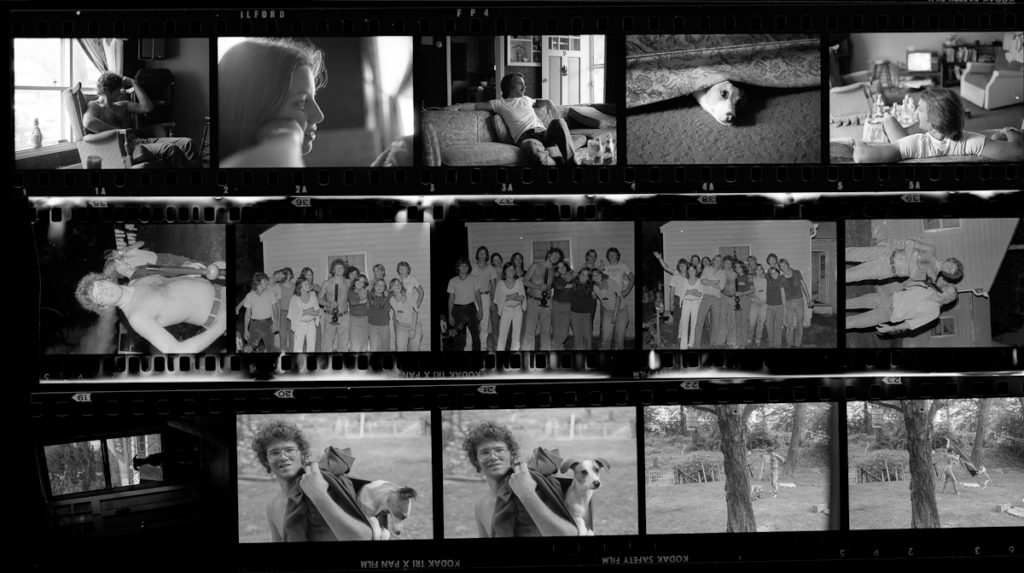

Fun Times at 9 Grand St circa 1977

I’ve been thinking a lot about photography and memory since I read Sally Mann’s Hold Still. Sally Mann is a favorite of mine. She’s made her name documenting life and family growing up in the Shenandoah Valley. Her photography is beautiful and moving and anyone with an interest in documentary or fine art photography should be familiar with it. She’s also a brilliant writer and a strikingly beautiful woman even now. I won’t lie – I’ve got a serious crush on her. Unlike most books written by photographers or about photography, Hold Still is a great read, both as an auto-biographical narrative and as a means to understand Ms. Mann’s photography. It’s the product of a lifetime spent documenting her life in an intentional way, a lesson of the payoff for photographers with the foresight to habitually record the quotidian details of everyday life.

Hold Still got me thinking about the emotional aspect of memory, how memories change over the years, some taking on broader emotional meaning and some fading to irrelevancy. It’s inevitable to an extent, new experiences encoding over old memories and changing those older memory’s salience, this being the normal process of how humans form a narrative of their lives. In particular, what I’ve been thinking about is how my interest in photography affected that process, warping it in a way that tracks the intensity of my photographic interest over the years.

Hold Still got me thinking about the emotional aspect of memory, how memories change over the years, some taking on broader emotional meaning and some fading to irrelevancy. It’s inevitable to an extent, new experiences encoding over old memories and changing those older memory’s salience, this being the normal process of how humans form a narrative of their lives. In particular, what I’ve been thinking about is how my interest in photography affected that process, warping it in a way that tracks the intensity of my photographic interest over the years.

In 1977 I was 18, a complete and total fuck-up, having had decided a year before to boycott my senior year of high school at an evangelical church school to set out on my own, which brought me to 9 Grand St, where I – typical dropout – did drugs, drank beer, chased women ( girls actually), avoided work, and documented much of it with my beat up Nikon F and later my new Leica M5. Nobody I knew had a Leica or even knew what they were. Leica’s were those odd cameras you saw in the back of Modern Photography, completely unlike the SLR’s everyone was buying, rare and expensive and mysterious. I remember being fascinated that, unlike other rangefinder cameras, whose market by the 70’s had been reduced to inexpensive fixed-lens consumer grade snapshot shooters, you could change lenses on a Leica. Wow. For some reason, a rangefinder with a 21mm wide angle or 90mm tele with auxiliary finder intrigued me, being the sort of thing that would signal to happy-snappers that what I was doing photographically was serious. I eventually bought one, a story I won’t bore you with as I’ve mentioned it often elsewhere.

Above are two sequential frames taken in that house, as best I can tell from the first roll of film I ran through my new Leica, a 20 exposure roll of Ilford FP4. That’s me to the left, and on the right, my girlfriend at the time. I have a clear recollection of it: the shiny new M5 passed between us while I shot a test roll and tried to figure out my new camera. If I look smug and self-satisfied, it’s because I was. Young and handsome, a new Leica, attractive and willing girlfriend – perfect. Or, at least, that’s what I think when I look at those pictures. The reality at the time, meanwhile, less idyllic, just another confused kid trying to figure out where his life might take him.

That I even have these memories is because I memorialized them with a camera. Had I not, the specifics would be long forgotten, the young woman a blurred memory. She was a summer fling, nothing special, but it’s amazing to me the clarity of my memory of her, all of which comes back when I see the photograph – the way she talked, the way she moved, the small particulars that made her her. A few years later I got serious about my life – college, then graduate school, then law school, in the process developing my first real adult relationships with women – but those subsequent memories, the one’s I should remember with particularity, are often less precise, blurry to the point of irretrievability, because I had put my camera away to get on with life and hadn’t documented any of it.

*************

I recently read a study that claims photographing our experiences impairs our ability to remember them. That isn’t the case for me. What I’ve photographed over the years comes back viscerally to me when I review old negatives in a way those not photographed can’t. Looking through contact sheets from my Grand St years, I’d spy a person I hadn’t thought of in 40 years, and instantly their name and some buried memory involving them would come back to me.

The difference may be this: today, iPhone photography is so quick and easy, so constantly available, that it’s become a rote, unthinking activity. I watched 17 y/o’s at a birthday party last night, hundreds of photos snapped with iPhones – along with the required gathering around the screen to look at the results, most destined for the digital trash can. Watching these kids – the same age as I was when I took those Grand St photos, I couldn’t help think that they were missing much of the experience itself, staring at their screens, texting instead of chatting, obsessively photographing the particulars – the food, the drink, the conviviality forced for the camera – instead of experiencing it.

Either that, or it’s become a means of distancing oneself from an activity, a way of keeping reality at arm’s length. You see this in art museums or tourist destinations, people with phone out, staring at screens, not experiencing what’s around them.

Film photography has, for me, always been about being in the experience, both the experience of the photographic act and the experience of what’s in front of me. It brings with it a level of mindfulness, an intentionality that comes from a certain focus required of a manual camera and film. It’s the sort of mindfulness that creates enduring memories – and tangible negatives to refer to years later. I can still remember passing that Leica between us, 40 years ago, sitting in my living room on 9 Grand Street with that girl. I remember her name, the contours of her body, the things we did. Had I grown up in the digital age, I’m not sure I’d have either those photos or those memories. Something to think about.

Views: 2011