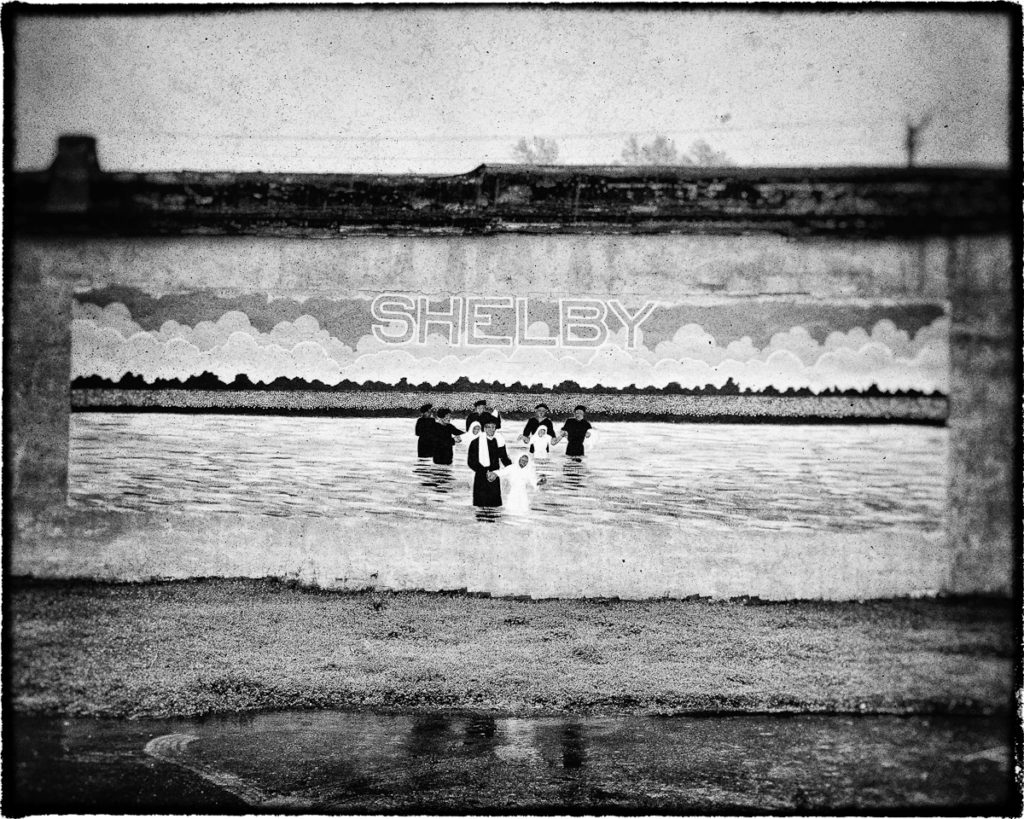

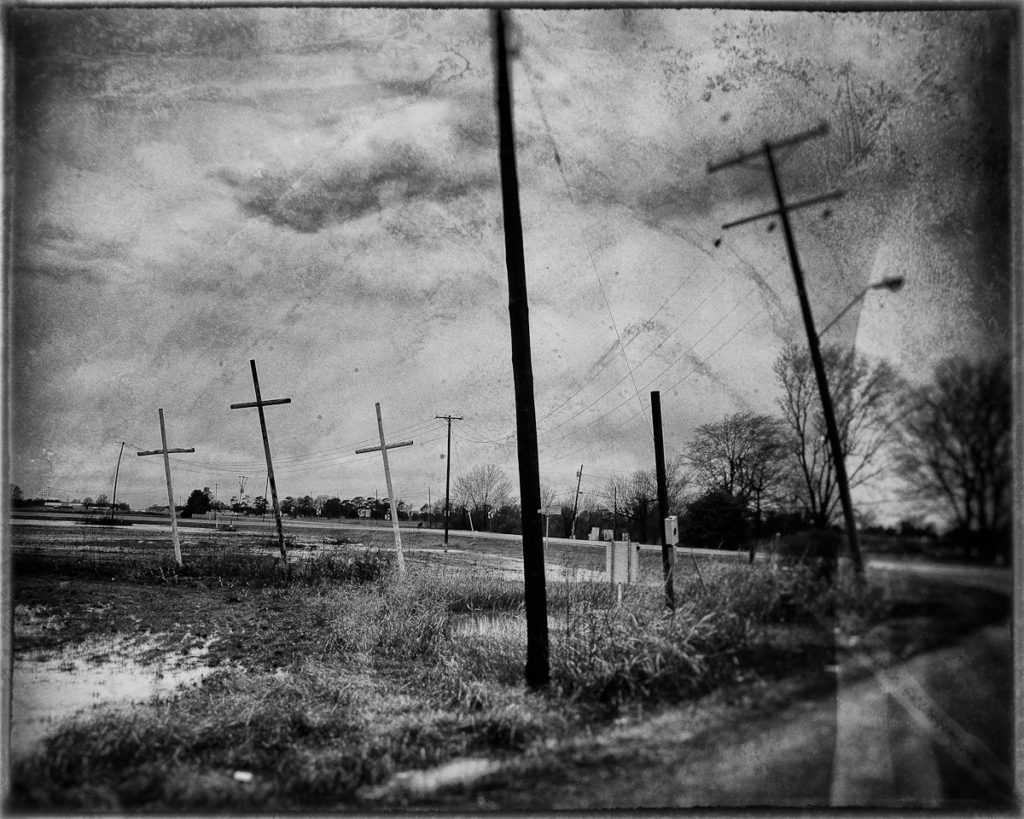

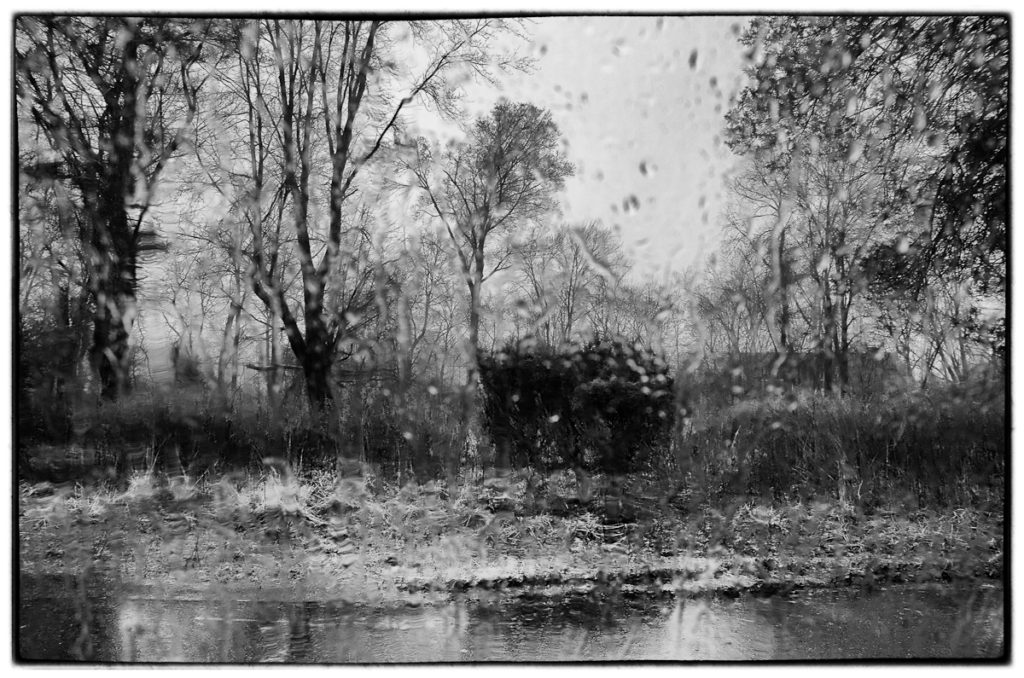

Intersection, Hwy 49 and Hwy 61, Clarksdale, Mississippi, 4×5 “Wet Plate”

Above is a picture of the Mississippi crossroads where blues legend Robert Johnson sold his soul to the Devil in return for the ability to play guitar. Unfortunately, it didn’t work out well for Mr. Johnson; while he created some great blues, he died young and broke and unrecognized, his grave somewhere unknown in the Delta. It’s been sung and talked about enough in popular American culture to have become a recognizable thing globally. The Crossroads. Located at the corner of Highway 61 and Highway 49 in Clarksdale, Mississippi, I took the photo on Highway 61 just north of the Highway 49 intersection so I could get the dead dog in the picture. Seemed appropriate. If you look to the right side of the photo you’ll see the traffic lights that sit at the intersection.

The bargain Johnson supposedly struck at this intersection is what we call “Faustian,” not really a ‘bargain’ at all, where someone trades something essential for personal gain, the gain being to receive what they think will make them happy but doesn’t. It makes things worse when all is said and done. If you’re familiar with classical European literature you’ve read about Dr. Faustus, the famous scientist who trades his spiritual and moral integrity for knowledge and power and then comes to a ruinous end. Writing a gloss on the legend in his play Faust, Goethe took some liberties with the story, now a wager between Dr Faust, who can find no meaning in his life, and Mephisto, the Devil, who promises to give his life meaning if Faust agrees to serve him forever after.

The the story is this: a man strikes a deal, depriving himself of a freely-willed human future in return for the quick and easy, a quicksilver shortcut to the goal, and in the process loses the good of what he possessed without gaining anything better when it’s all done, in fact, what’s been gained is a much impoverished version of what he started with. It’s called “a deal with the Devil.”

*************

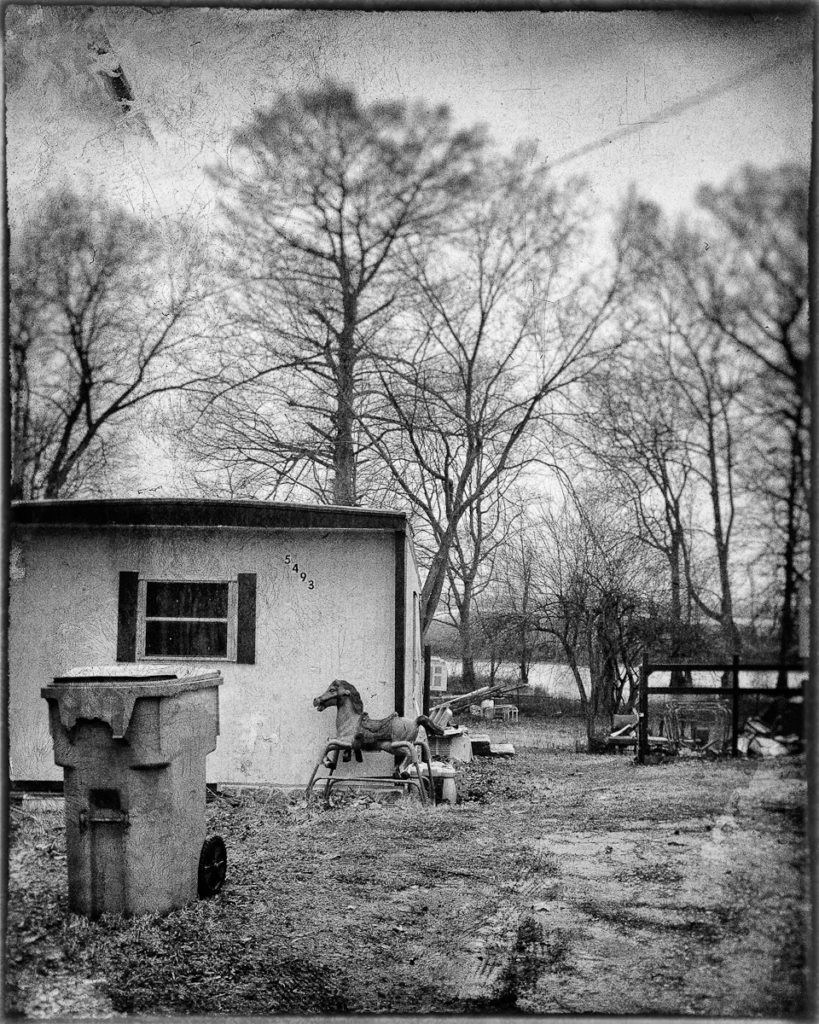

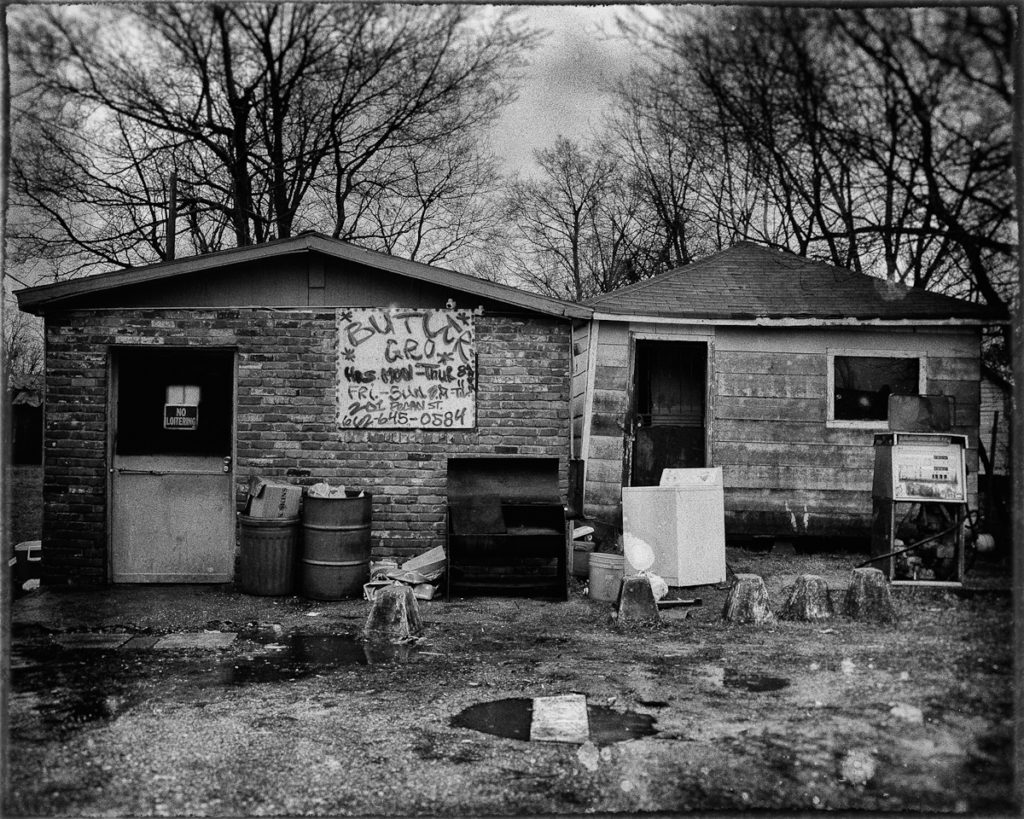

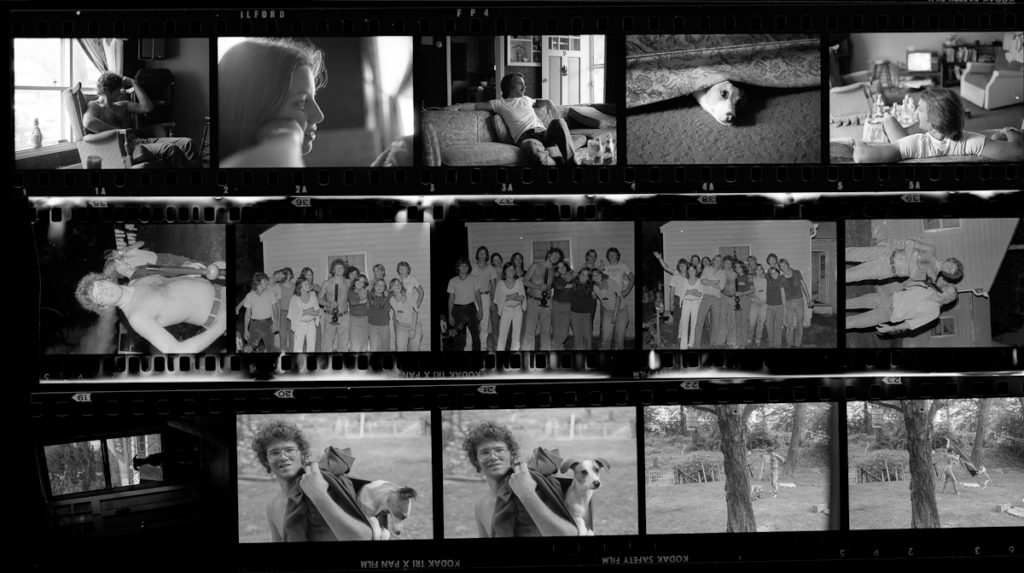

Somewhere in the Mississippi Delta (Can’t Remember), 4×5 “Wet Plate”

As I mentioned in a previous post, I’d recently read Sally Mann’s Hold Still, a great read if you’re interested in the interior lives and thought processes of artists. There’s few photographers I’d class as ‘artists,’ but Sally Mann would be one of them, so I was interested to read what she had to say. In the process, I got to thinking about her use of a view camera and the slow, deliberate nature of her craft. It’s so unlike what digital, or even 35mm film, allows. I also like the results. There’s nothing more beautiful than an 8×10 b&w contact print. She’s also a Southerner, as am I, with an eye for the Gothic details of life in Deep South America. Her recent work involved a trip from Memphis to New Orleans via the Mississippi Delta taking pictures of things that caught her eye along the way. She did it with her view camera and with wet plates, liquid emulsions she brushed onto 8×10 glass plates and used as the negatives for her 8×10. In addition to involving a lot of prep work, she’d also have to immediately develop the plates in the back of her pickup under a black cloth. What she gets when she gets a good shot is something really interesting, imprecise, sometimes blurry and diffuse, often with serendipitous features that give a powerful character to the final prints. It’s obviously a difficult process to master, which gives heft to the work because they’re the result of skill and hard mastery. They say “this is something that took skill and hard work and incredible perseverance, and in the end produced something beautiful.”

Which got me thinking: I’ve been through the Delta a number of times with my camera, so I know it well, and I’ve also spent some time with alternative processes, and – you know – the idea of shooting the Delta with a view camera and some funky emulsions sounded like a great trip, so I started thinking of what I’d need to do the work. I’ve got a view camera and tripod, I’ve got the time; all I’d really need to do is figure out how to do the emulsions. Or even simpler, I could do set pieces on regular 8×10 negative film – they still make it – and then contact print it. That would be a fun project, and certainly one I could exhibit if the work was decent.

But then I had a further thought: I wonder, in all of the post-processing software I’ve got loaded onto my computer but never much use, do I have a “wet plate emulation?” I searched around and, yes, I did. So…I pulled up my Mississippi Delta photos and after cropping them to 4×5 for authenticity, started running a few of them through the wet plate emulation and damn!, a lot of them looked really good. Exhibition quality if printed on good pigment paper at 8×10. It really is powerful work if I might say so myself.

*************

But…there’s something wrong with this. I’m not sure I can articulate it, except to say that my ‘wet plates’ and Sally Mann’s wet plates occupy two different poles of artistic merit. Assuming you think my wet plates are as evocative as Ms. Mann’s from a visual standpoint, you could say they have equal creative merit, but is that really the criterion for assessing the relative worth of our Delta work, or is there something more, something more evanescent but crucial, that’s present in her work and absent in mine?

I would argue there is. Her’s possess an authenticity that mine mimics, even though they might look similar technically. She dragged an 8×10 view camera around for 1000 miles, jugs of dangerous chemicals in tow, which relegated her going places that would accommodate her. I drove around, pointed my Leica M8 at everything and shot. At each location, she’d spend an hour or two developing her plates, drying them, inspecting them, repeating the process until she got what she wanted. I pushed a shutter and chimped the results, brought thousands back on an SD card and ran the keepers thru emulation software on my Mac. Once home she fastidiously contact printed her best plates, producing 20 or so exquisite silver prints. I tee’d up my Epson R3000, loaded in the Moab Lasal Exhibition Luster Paper, and effortlessly printed off 40 8×10 prints that could pass in a pinch for contact prints.

So…am I going to exhibit my Delta “wet prints?” No. Because to do so would be deceptive, although many photographers born in the digital age might disagree. It’s the result that matters, right? Tell that to Sally Mann. That’s the Devil’s Bargain we’ve made with digital. What used to be the product of craft and deep skill is now just a mouse click away. We still get the same results, but the honest pride of work well done has been taken from the process. We’ve wished for one thing and received another in the guise of the quick and easy, the thing that we thought would liberate us. Same thing Robert Johnson did at those crossroads in Clarksdale, Mississsippi, the story old as civilization.