Ludwig Wittgenstein. He Resigned His Chair in Philosophy at Cambridge University to Become a Shepard.

The last few posts we’ve been discussing the “ontology” of photography – what, at base, photography is. For the thinkers I’ve already written of – Jean-Paul Sartre, Susan Sontag, Roland Barthes, Jean Baudrillard – the important thing about photography, its claim on our imagination, is its relationship to what’s “real.” For Roland Barthes, whom we’ve discussed at length, photography was a memento mori, indexical evidence of what had been, and this is what gives it its uniqueness as a medium of representation. Similarly, for Sontag, photography was a “stenciling off of the real,” conclusive evidence proving the reality of the photo’s subject. Both Sontag and Barthes wrote prior to the digital age,

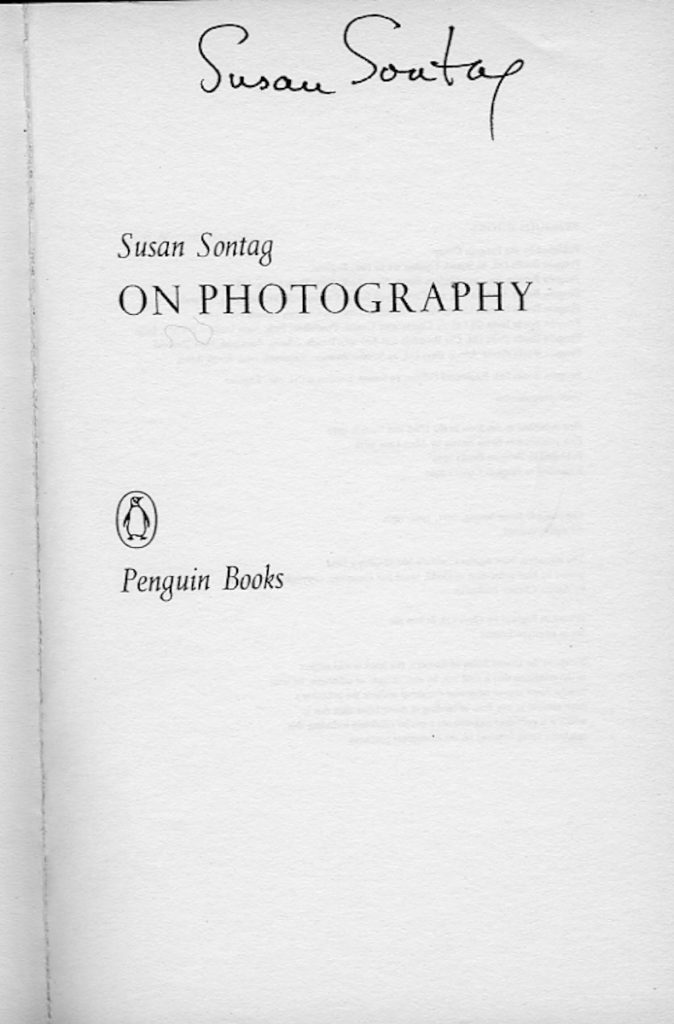

Barthes meeting his maker via a truck in Paris in 1980 (there’s an interesting recent French novel The Seventh Function of Language, by Laurent Binet, whose premise is that Barthes was murdered by other Semioticians), while Sontag did live into the digital age but never updated her thinking about photography (I met her in Paris in 2004, where she signed my copy of On Photography…which, you gotta admit, is pretty cool).

Barthes meeting his maker via a truck in Paris in 1980 (there’s an interesting recent French novel The Seventh Function of Language, by Laurent Binet, whose premise is that Barthes was murdered by other Semioticians), while Sontag did live into the digital age but never updated her thinking about photography (I met her in Paris in 2004, where she signed my copy of On Photography…which, you gotta admit, is pretty cool).

Sartre, Sontag, Barthes all saw photography as basically honest, allowing us access to the real, a function of its “indexicality.” They weren’t questioning the truth of photography itself. Baudrillard might be, but his issue was with the severing of indexicality, which is about a type of photography and not photography itself.

Now, I’d like to discuss an Austrian born “analytic” philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, whose criticism of photography is of a different type. Wittgenstein’s critique goes to photography’s roots, where even traditional indexical photography – the analog process where light stencils itself onto film – isn’t truthful. This is ironic because, for Wittgenstein, photography is a practical expression of his preferred means of perception, his motto being “Don’t think, look!”

*************

Wittgenstein (1889-1951) worked primarily in logic, the philosophy of mathematics, the philosophy of mind, and the philosophy of language. From 1929 to 1947, he taught Philosophy of Language at Cambridge. While alive he published one book, the 75-page Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921), one article and one book review. A second work, Philosophical Investigations, contradicting everything he had espoused in the Tractatus, was published posthumously in 1953. Bertrand Russell, Wittgenstein’s mentor – and subsequent protege – himself a philosopher of enduring significance, described him as “the most perfect example I have ever known of genius, ” and Wittgenstein is now considered a seminal figure in Western Philosophy. A survey of American university professors ranked the Investigations the most important philosophical work of the 20th-century.

Once you get past the work’s complexity, Wittgenstein’s main point is simple – not everything we know can be put into words. While most things can be said some things must be shown. In this, he agreed with Thoreau, who said that ” you can’t say more than you can see,” except that Wittgenstein goes further than Thoreau and believes you can see much more than you can say. More can be shown than can be said, because, for Wittgenstein, to think was not to mentally verbalize but rather to picture.

“Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent,” is the famous last sentence of the Tractatus. Unspoken is Wittgenstein’s premise the things about which we must be silent are actually the most important ( do you see what he did there?). We can’t verbally reason our way to these truths, as Western thought has tried to do since Socrates, but rather we need to look.

**************

Wittgenstein was Into Selfies Long Before it was a Thing

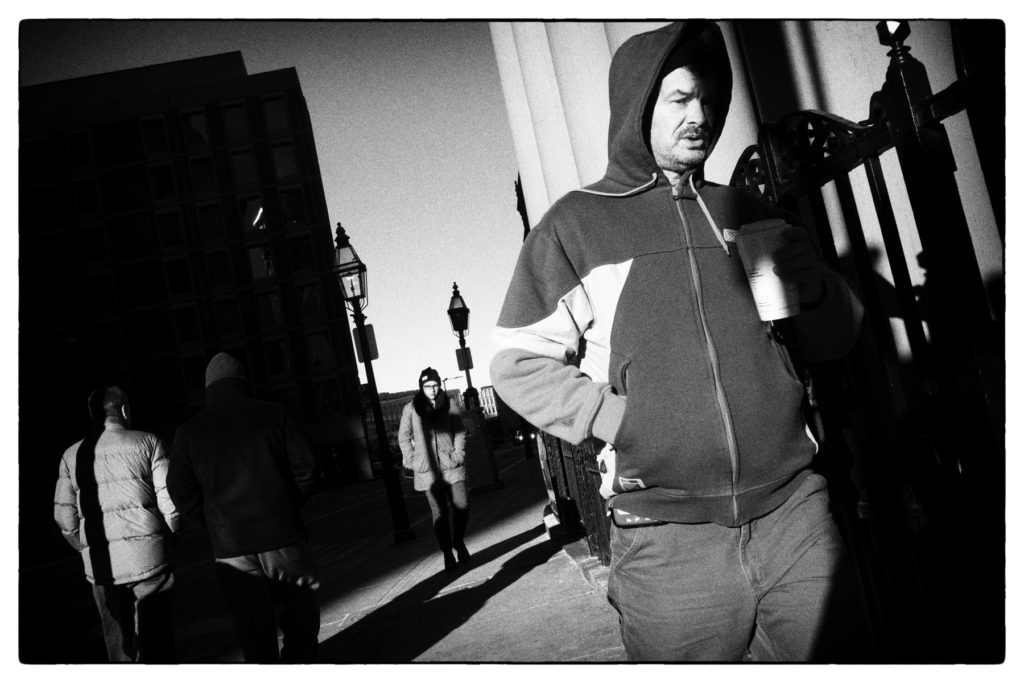

Given that, it shouldn’t surprise you that Wittgenstein was a photography buff. Apparently, he loved photography, annoying his friends by constantly taking pictures of them with cheap cameras. But, in spite of his interest, photography represented its own conundrum for Wittgenstein. It was not the problem of indexicality as it had been for Barthes et al. For him the problem was more fundamental, involving larger issues of visual representation and its capacity to reflect “the truth” of a thing.