Rungis, Paris, 2004. Sometimes you’ve got to look hard to see what’s in front of you

If I were to describe, as best I’m able, what I’ve spent a lifetime of photography doing, it would be this: I’ve tried to document “the plain sense” of the things that constitute my life. Putting words to something which is intuitive and ineffable, it’s the intellectual equivalent of trying to squeeze an elephant into a mason jar – it doesn’t capture all of the buried motivations, but it gets as close as words allow, so it’ll have to do. I’ve always respected Garry Winogrand’s explanation for why he photographed things, “to see how they look when photographed,” which is as good a no bullshit, anti-Artspeak explanation as I’ve yet heard.

All of this assumes my photography has any purpose. I can’t articulate any overarching explanation for why I photograph or why I photograph what I photograph. Attempts feel like ex post facto justifications for something that can’t put into words, the logic behind it being ineffable. My photography just is; the subject creates itself. I point the camera at things that make sense to me to photograph. Any needed rationalizations come later, at the point of editing, selecting, sequencing, articulating. What I’m left with defines what I’ve seen and how I’ve seen it.

*************

Portland. I love this Photo. Why? Hard to Say

There’s nothing more pretentious than an artist explaining his work. Invariably, the explanation sounds silly, forced, as if he has no real understanding of what he’s been doing. Some of my most awkward moments have been those times when a gallery visitor has asked me what a painting “means.” Anything you say will sound pretentious and foolish.*** The best response I’ve been able to come up with is “I don’t know, you tell me,” except that’s not really correct either. The honest response would be “I can’t articulate its meaning…but I know what it is. As for you, interpret it as you will.”

Our creative motivations are often opaque to us, but always larger than the restrictions imposed on them by words. Putting words to them often circumscribes rather than illustrates the work and, as such, weakens the work itself, boxing it in with artificial constraints. Dragan Novakovic, the subject of a recent post, described the impetus behind his early 70’s British photos, a coherent body of photographs if there ever was one: “I wish I could tell you that these photos are the fruit of a well-thought-out project and expatiate upon it (projects and concepts seem to be all the rage these days), but the truth is, they are all completely random shots.” I admire him for saying that. It takes courage to admit your conceptual naivete; in Mr. Novakovic’s defense, his photographs are so good they need no explanation. Whatever ‘naivety’ Novakovic possesses isn’t born of ignorance but rather his intuitive understanding that whatever he’s done – inspirationally and procedurally – can’t be reduced to an explanation. The explanation is the work itself.

One of my favorite recent photo books is Dive Dark Dream Slow by Melissa Catanese. No words, just a sequence of vernacular photos from the photography collection of a guy who collected anonymous 20th century “found” photography, the kind of photographs we paste into albums or stash in boxes stored in the attic along with other detritus of our lives. Ms. Catanese is the curator of the book in the sense larger than simply “editing” it. The work is really her’s, in that through her selection, sequencing and presentation of the photos she’s created something unique to her, something apart from the intentions of the various photographers or of the collector himself. What it “means”? Clearly, it “means” something to Ms. Catanese given the constraints she imposed on the materials. As to what that meaning is, she’s not saying, or, more precisely, she seems to be saying “It means what you make it mean.” And that’s the fascination of it. We as viewer get to give it a meaning.

One of my favorite recent photo books is Dive Dark Dream Slow by Melissa Catanese. No words, just a sequence of vernacular photos from the photography collection of a guy who collected anonymous 20th century “found” photography, the kind of photographs we paste into albums or stash in boxes stored in the attic along with other detritus of our lives. Ms. Catanese is the curator of the book in the sense larger than simply “editing” it. The work is really her’s, in that through her selection, sequencing and presentation of the photos she’s created something unique to her, something apart from the intentions of the various photographers or of the collector himself. What it “means”? Clearly, it “means” something to Ms. Catanese given the constraints she imposed on the materials. As to what that meaning is, she’s not saying, or, more precisely, she seems to be saying “It means what you make it mean.” And that’s the fascination of it. We as viewer get to give it a meaning.

************

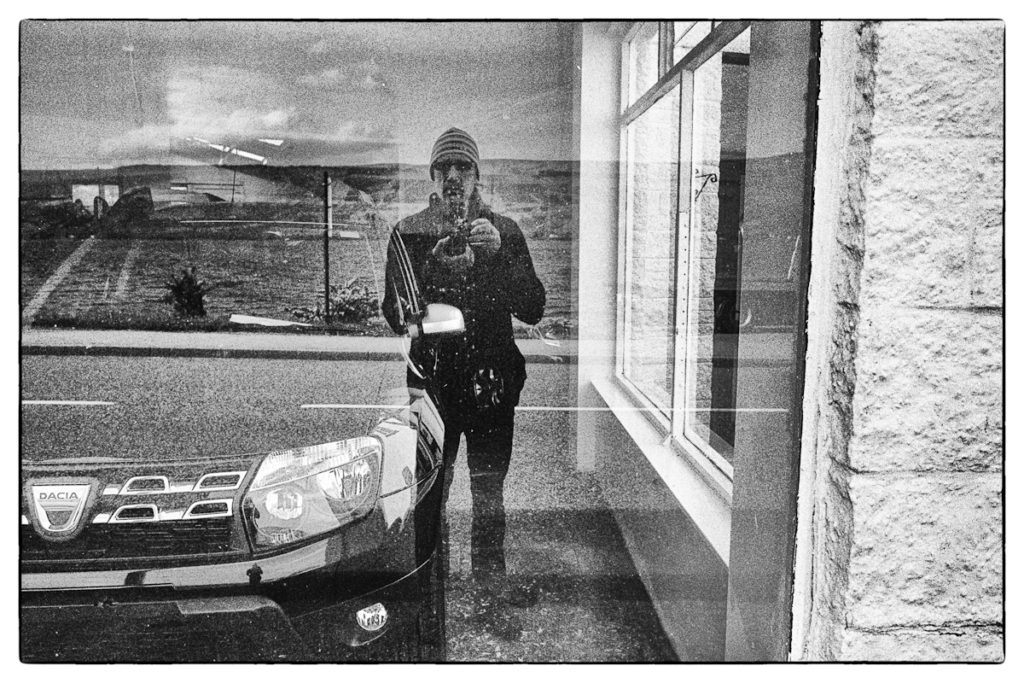

Loch Ness, Scotland 2016. There’s a monster down there somewhere…or so I’m told.

Photography, for me, is an activity in service to an internal, idiosyncratic dynamic. I’ve never made photographs for someone else’s consumption or delectation; I’ve made them to give exterior form to something interior. Hence the doing of it itself has been the payoff, sort of like going to therapy. Certainly there’s a sense of wanting to do it well, but ‘doing it well’ has little to do with what other people think of it, which to me is largely irrelevant. Doing it well means feeling as if what I’ve created expresses some logic internal to me. It’s got to resonate with me. If it does, I consider it done well; if it doesn’t, it isn’t, even if other people like it.

The reason why photography has interested me for so long is because it’s not been ‘about’ anything. I’ve never viewed it as a means to anything, and when I’ve put myself in a position to view it as a means to make a living I’ve quickly, and radically, lost interest. Whatever it is, it isn’t about that.

So, with all that said….I’ll try to articulate what I’ve been trying to do in a lifetime of photography. If it is anything, its been my attempt to locate my self, to give it contours by locating it in a specific time and place [see how pretentious that sounds?]. It’s been my attempt, to document what was (is) me. At heart I’m a documentarian. Anything said beyond that will just muddy the waters, so don’t ask me to explain.

*** My Artist Statement, generated after a few bourbons:

Ever since I was a student I’ve been fascinated by the ontology of mind. My work – scattered across various media yet forming a coherent whole – explores the relationship between subjective profundities and banal, prolifigate experience. Influences as diverse as Homer, Pynchon, Schopenhauer, van Gogh, Joyce, Aristotle, Coltrane, Pollock, and Pound inform my creative narratives. What started out as naive childish hope is now corroded by the hegemony of time, yet it has been leavened by the rich fund of common experience and memory. My work is the synthesis of these things, a re-imagining of what time sweeps into the past, the flux of phenomena screened through the bounded conceptual schema that is me, leaving the receptive clues to solipsistic meaning, assuming, of course, that we, in radical subjectivity, may ‘share’ a solipsism in any meaningful way.

Interesting thoughts. It’s something that I’m thinking about for quite some time now. Like you, I am not interested in reproducing pictures with widely agreed on aesthetic appeal. This got me thinking why I am taking the pictures I’m interested in, and what makes particular pictures work for me and others not. I started to read about definitions of the beautiful and about aesthetics as a philosophical discipline (this is my way of doing things). The findings were very interesting: From the outset of modern aesthetics (Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten c. 1750), philosophers mostly agree that experiencing aesthetical objects provides a kind of cognition/insight, similarly to scientific work and logical reasoning.

The fundamental difference to science/logic is that the cognition/insight gained through aesthetics is *not conceptual*, but rather intuitive.

Since we use words to shape concepts, I conclude that verbal concepts as a starting point for creating art are mostly pointless.

I organize my own work as projects; the iconic masterpiece photograph is not my thing. My way of working is to simply start taking pictures of things/places which I find compelling. Over time, there will be pictures which stand out from the bulk. These are my “beacons” which guide the refinement of the project – and if I’m lucky, a concept will emerge. It’s still hard to put the concept into words, but the “beacon” pictures kind of circumscribe what I’m after, I’m dialing in on the thing.

I believe some words about a project are helpful and interesting for the viewer – but if we could use words, why take pictures in the first place?

BTW, you have an interesting blog. Though I don’t use a film Leica, but a digital SLR, and work in color, I enjoy posts like this and also about jazz.

Best, Thomas

That’s a wonderful exercise in curator-speak! Congratulations are due.

I opted for brevity in my website declaration: WYSIWYG.

I thought it might be difficult for people to argue with an artist’s statement like that. Of course, there is ever the danger that the argument is diverted to one about whether or not the word artist might be out of place in the discussion, should there be a discussion which, so far, is something still in the future, probably a future beyond my period of personal interest.

Seriously, though, you really have spoken for many of us in describing the thought process behind some forms of non-pro photography. That said, as I was largely in the fortunate position of being given a gig and told to get on with it without many conditions being attached, to a large extent there wasn’t much to my work that was more than just an extension of my own mental makeup. After all, the work I got was because of what I was able to produce by the simple expedient of not really being able to be anyone else. On top of that, I did very little photography that was not work or work-related in some manner: I wasn’t really interested in anything else. However, once retirement reared its ugly head, photography went onto a distant back-burner until the death of my wife, at which point it became my survival technique and after a few lost years of this and thating, I came to a point where I discovered that my interests were really limited to a sort of Saul Leiter ethic, but mostly in black and white. I’ve done pretty much nothing else for a few years now.

But I would still have to join you in declaring that I have no real way of articulating either the sense of, or deeper motivations that make me press the button; all I can say is that I feel something reaching out to me, not really the other way around.

The best I can do is to write brief titles to my pictures. They kinda suggest what I think may have been suggested to me by whatever connected with me.

What an excellent piece Tim, something that I am incapable of. Indeed you suggested that I send you a piece, but so far I have failed to come up with anything worthwhile.

I have never willingly published any of my pictures, indeed a good friend who describes herself as a “professional photographer” asked me when dining in a restaurant, why I had that old camera with me, and could she see some of my “work” (they are just snapshots!). I told her that I liked it, it made me hesitate before I clicked the button, but there was nothing for her to see, it was for me. I would add that I also use digital cameras and colour film, I am not fussy.

Anyway, recently I keep reading things that resonate with me, this piece of yours (along with a good few of your earlier pieces), the comment by Rob above… (WYSIWYG indeed), a manifesto by Filmosaurus a couple of weeks back (a photograph doesn’t necessarily represent anything, it is a thing in itself), and weirdly the book by Sally Mann, who even though she seems to be in possession of a massive ego, does have some interesting stuff to say.

But when it comes down to it, I like buying cameras, I like walking with a camera it seems to make one look more intensively at the surroundings, I like messing around in the kitchen developing film and scanning the negatives and I don’t really feel the need to have anyone look/see my pictures, which might mean that I am ashamed of them, or I have a humungous ego.

I decided to refresh my rather poor darkroom skills and took a course a couple of weeks back, one of the blokes on the course introduced himself as someone who likes “things”, and certainly things are what you get when you take a snap, then develop and print it.

So as a result of recent events, I am publishing a few pictures on “Leica Fotopark” and I am going to use the darkroom much more than hitherto.

Nothing is written in stone.