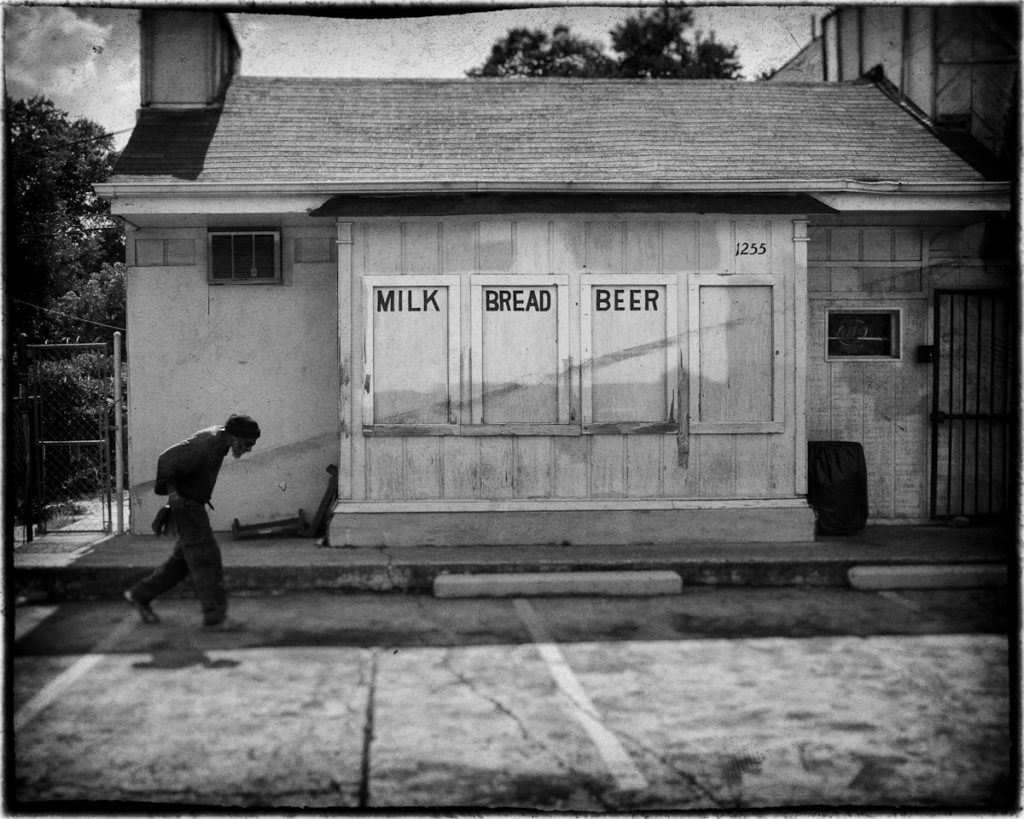

Is this a picture of a broken down hobby horse, or it it something else? Or is it both, or neither?

While there’s a lot of great photography, there are few, if any, thoughtful books about photography and what it means. Off the top of my head I can think of a few worth reading: Susan Sontag’s On Photography and Regarding the Pain of Others, Errol Morris’ Believing is Seeing, maybe Barthes’ Camera Lucida if for no other reason then everyone seems to refer to it, many, I suspect, without having read it. Most of the rest is poorly written and even more poorly thought through, crammed full of “post-structuralist” academic jargon, jargon being the best evidence that the writer doesn’t have any real idea what they’re talking about. Frankly, you’ll learn more about photographs by reading Vincent van Gogh’s Letters to Theo or Naifeh and Smith’s incredible biography of him, Van Gogh: A Life, both which will give you insight into what personal vision is, how one develops it and how easy it is to compromise it unless you steadfastly guard it.

For many of us, photography isn’t simply a technology for informing or recording. It is more about the aesthetic and emotional payoff for us as the photographer, being able to create something that communicates what we see and how we see it. Every good photo has something original in its approach, going against the grain of common seeing, evidence of the idiosyncratic way a single person sees and thinks. Good photographers, ones who create meaningful, original work, can’t do it any other way: their way of seeing is necessarily as idiosyncratic as their mind and body, and to produce photos without that idiosyncracy would be dishonest to themselves and their audience. Apeing someone else’s style is for the neophyte or the creatively barren.

*************

A photograph is, to use a metaphor, a visual poem. We read a poem because we want to know how the poet “sees” the subject of the poem. We read it for what Barthes calls its punctum: that peculiar way of seeing, or writing (which in a poem is the same thing)—the poet’s style. Likewise, we read a novel or an essay not simply to learn something but to see through someone’s eyes, to follow the traces of their mind on the page as they come to terms with a theme or an idea or an experience. But it’s not a static one-way thing. It’s also about discovering what we think of what the poet thinks. Writing poetry is collaboration between poet and reader, both bringing their persons to the text.

So too with photography. A photograph operates as both a document and a creation. The level at which it gets interpreted depends on the viewer. Good photography is a collaborative effort, requiring a skilled and creative photographer and an intelligent and receptive viewer. Roland Barthes makes the distinction, in Camera Lucida, between two planes of the photograph: the studium, which is the explicit subject of the image, the information we learn from it; and the punctum, “that aspect (often a detail) of a photograph that holds our gaze without condescending to mere meaning or beauty.” The punctum exists in the head of the viewer; it may change from person to person, or it may change for the same viewer at different viewings. In my experience, a photo can mean different things to me at different times.

This, obviously, has implications for one’s ability to write “about” a photograph. If “what it means” changes even for the photographer – not even mentioning the role the viewer plays – then explaining it with language seems a fool’s errand at best. There is nothing more pretentious than photographers trying to “explain” their work. My advice for those of you who think you need to: the work speaks for itself. If you feel you need to explain, the work probably isn’t very good in the first place and your explanation will simply box you in and further diminish what little impact the work itself might have. Better to shut up and let your audience decide for themselves. What they think of it may differ from what you think. That’s OK. There’s room for both, by necessity.

I think John Szarkowski did the best job writing about the “why” of the photograph and really, the photographer. In particular, his two books, “The Photographer’s Eye” and “Mirrors and Windows” did a great job explaining the slippery and subjective aspects of photography. I recommend them!

Steve W

I think that if you can fully explain your picture with words, you should probably have written an essay rather than taken a photograph.

Conversely, I think that if you cannot talk *around* your photograph, give me some related words and ideas, some failed attempts to explain it, then your photograph probably isn’t very good.

You have a point. I like to put a title to my snaps because, in so doing, I get a little verbal charge over and above the visual.

These titles usually make absolute sense at their christening, but now and again, on revisits, I wonder what the hell I’d been thinking about. I suppose that’s the price of having a quiet smile to oneself. That third parties may also wonder is neither here nor there: it’s done for my personal pleasure, which is enough for me. Very rarely, the title springs to mind as I shoot, but it usually comes as part of the processing job, something that is inspired (that sounds a bit heavy!) as the image metamorphoses from straight, flat record to its ultimate state.

Rob

The moment you mention van Gogh’s ‘Letters to Theo’ I think: The daybooks of Edward Weston. Those two volumes never fail to get me back to the essence of photography.

I have never read either Willem, so that is probably my loss. Your comment made me go and look for the Weston books though, and I have ordered them.

The main reason, during my search for the best value, I stumbled on this little quote:

“I would say to any artist, don’t be repressed in your work, dare to experiment. Consider any urge, if in a new direction all the better, as a gift from the Gods not to be lightly denied by convention or a priori concept. Our time is becoming more and more bound by logic, absolute rationalism; this is a straitjacket It is the boredom and narrowness which rises directly from mediocre mass thinking.”

Edward Weston

It’s like he knew about mobile phones in the 1930’s., and had clearly been exposed to socialism.

Well, he did photograph vegetables.

Yes. Van Gogh’s Letters to his brother are as profound as his painting. Vincent was a remarkable man in many ways.

I never give any narative to any of my photo’s, it is what it is. I see what I see and you will see what you will see in my or any photographs. I recently read a book called Why photography matters by Jerry L Thompson its about how photographs works not only as an artistic medium also as a way of knowing. pretty interesting you might want to check it out.

Dominique.

Thank you for a great article. I think there are two more authors who write about photography in a meaningful way: John Berger and Karl Ove Knausgard in their essays. Saying this just in case you have not seen their essays yet. Would be interested to hear your opinion about them.

Best regards

I’d thoroughly recommend “The pleasures of good photographs” (Gerry Badger, Aperture). And not just because he appreciates Atget, Szarkowski and Evans. For the others: something about Sontag always seemed dated and Barthes, well, it is equally incomprehensible in French!

You’re just in time for my post on Barthes, Henry.