Sigma sd Quattro, ISO 100, f 2.8 Handheld

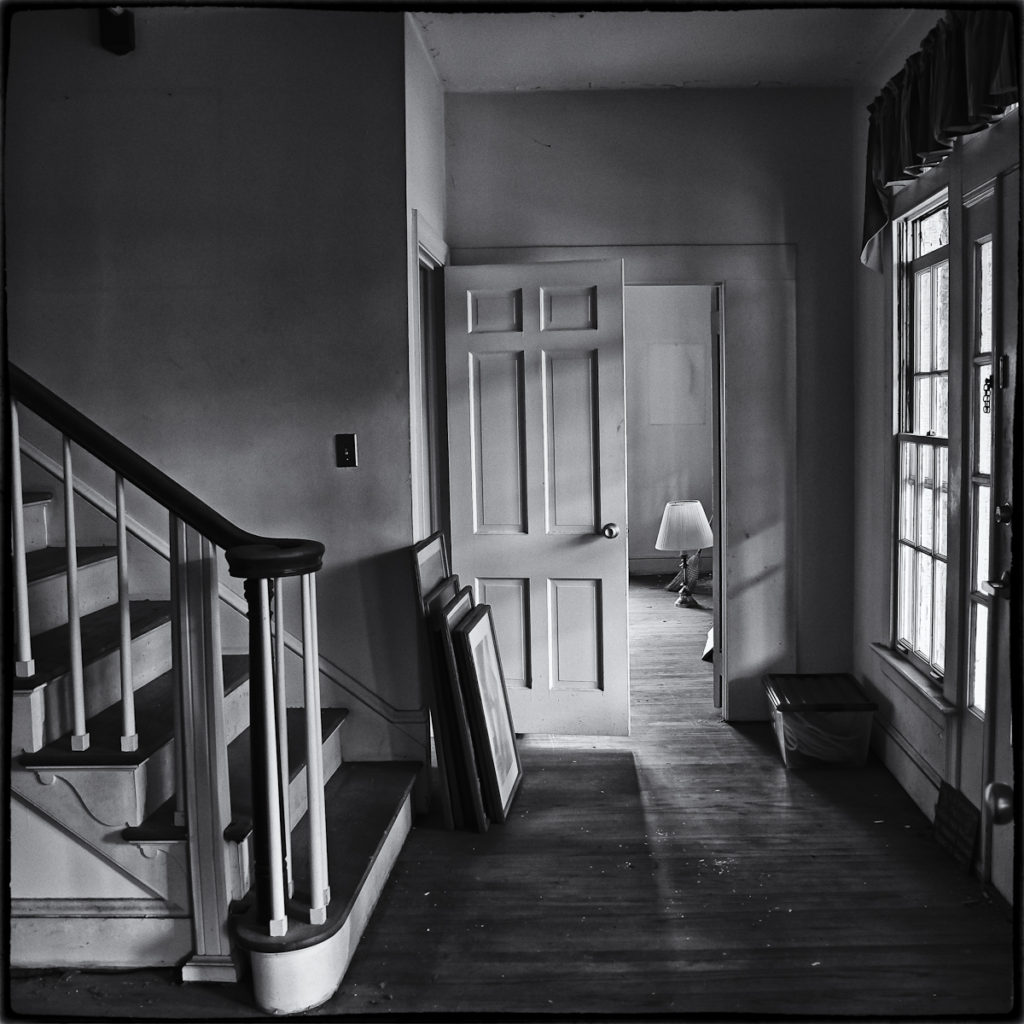

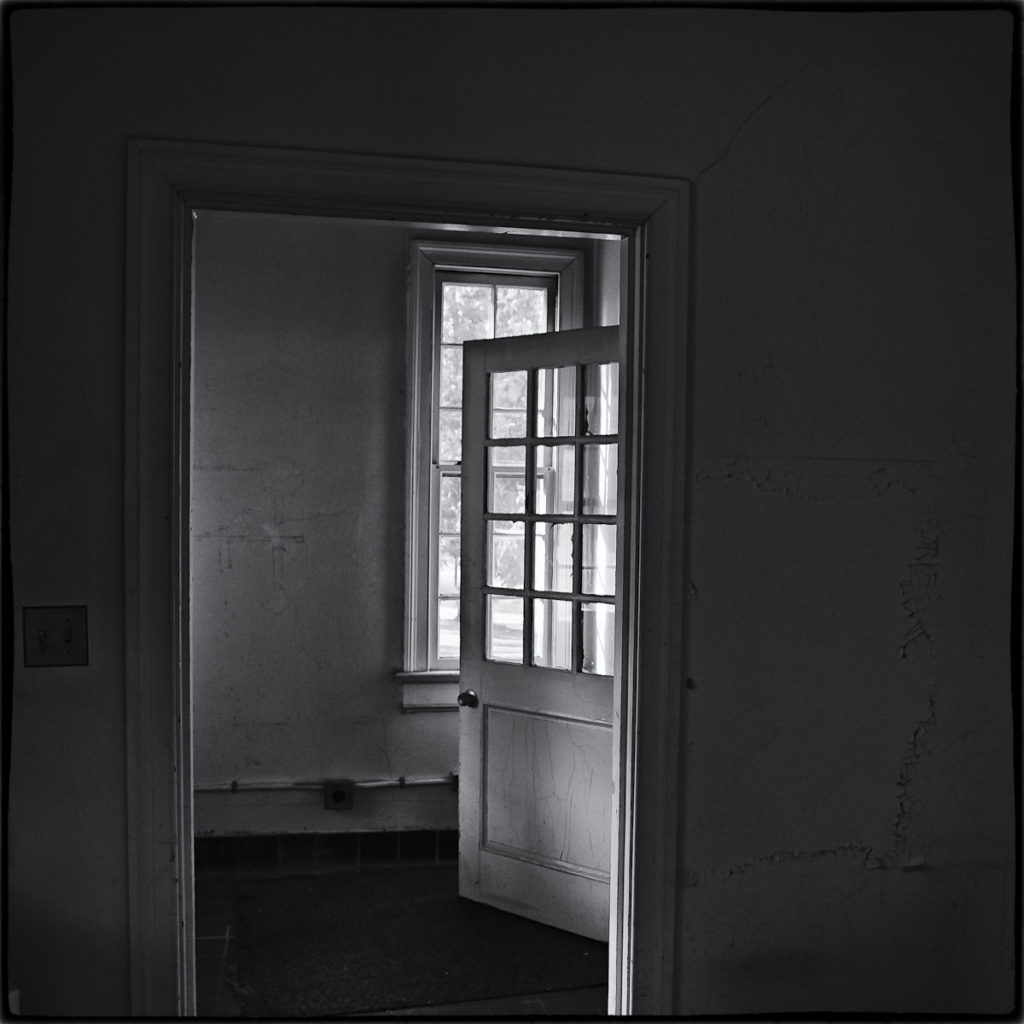

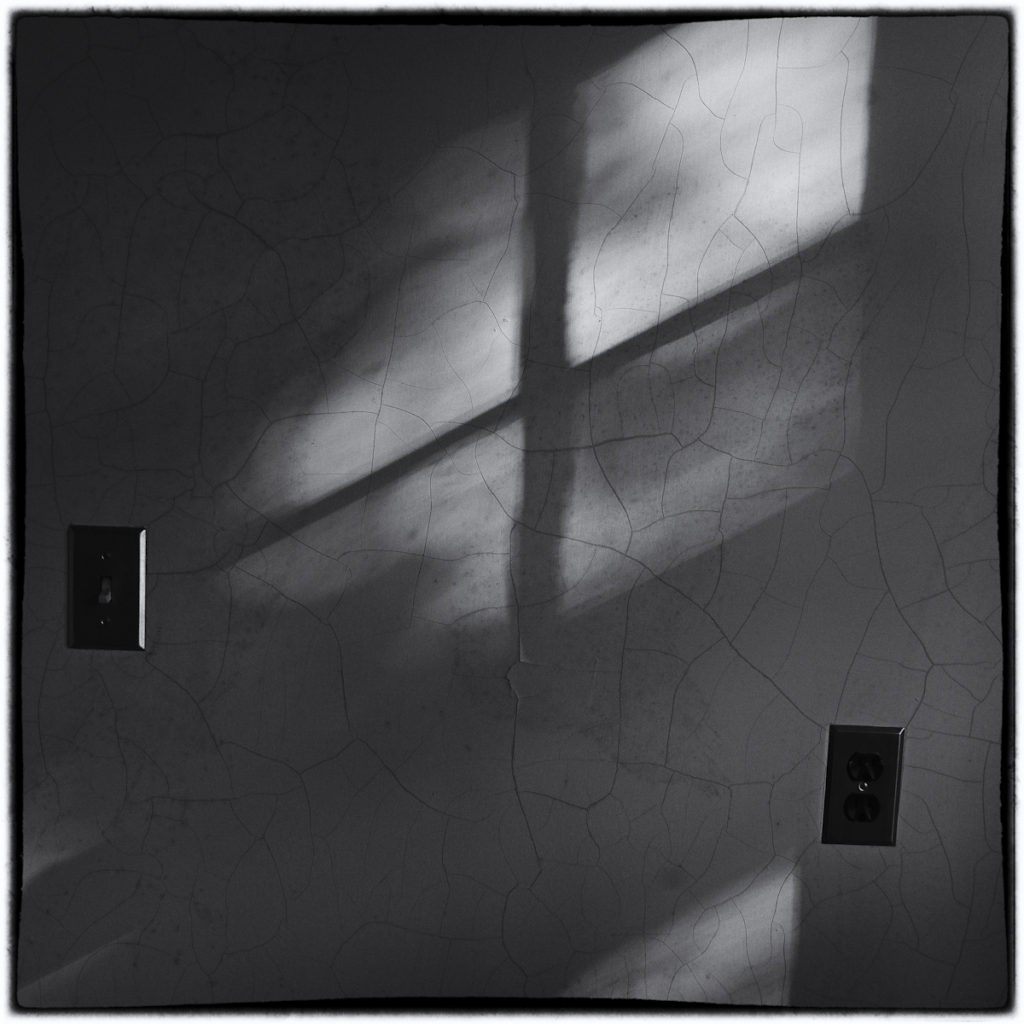

I’ve been engaged in an ongoing documentary project, photographing the grounds and buildings of the Dorothea Dix State Mental Hospital in Raleigh, North Carolina. (The photos that illustrate this piece are of the hospital director’s residence, now abandoned). The Dix campus is a stunningly beautiful piece of property that sits on the edge of downtown Raleigh. The city has been eyeing it for years, hoping to raze the hospital and buildings and convert the grounds to a public park. With the push to de-institutionalize mental health sufferers, the hospital and its numerous support buildings currently sit empty, falling into disrepair while waiting to be bulldozed and replaced with luxury hotels and manicured lawns.

I often walk my dog on the property, and when I do, I’ll usually make a point of taking a camera along with me, if for no other reason than it makes me look – really look – at what’s around me, and it affords the opportunity of recording it for posterity. One thing I’ve learned in 50 years of photographing things is that the things you most take for granted – the things you expect to always be there – are the things that ultimately aren’t. Time has a peculiar way of transforming the most ‘permanent’ of things.

I think, for example, of the year I spent in lower Manhattan in 1978, walking almost daily through the World Trade Center Plaza on my way to school on Broadway just north of the Twin Towers. I usually carried a camera – I was on my way to and from Art School studying photography – and yet I never bothered to photograph what was right in front of me because it all seemed so obvious, so blindingly ‘there’. In all my negatives from that time I find one photo – one – of the WTC towers, a basic tourist snap of the buildings themselves. In hindsight, I’d been given an incredible gift – and I’d squandered it. This, of course, is how we learn, if we learn at all. Often the most effective pedagogy is regret at missed opportunities.

*************

Sigma sd Quattro, ISO 100, f 2.8 Handheld 1/30th Second

As I’d expected to remain outside in the late-afternoon sun, I’d taken my Sigma sd Quattro with 17-50 2.8. Not exactly the camera I’d have taken were I expecting to be photographing inside, given the Sigma’s reputation for lack of usability at higher ISOs ( I most profitably use it at 100 ISO), but I’d tried a back door to the residence, found it open, and knew I’d probably not have the opportunity again, so in I went (missed opportunities and all that). All of the photos used to illustrate this piece were shot handheld at 100 ISO…with an f 1:2.8 lens. Indoors obviously. The point being, it can be done. Those of us raised shooting film became quite adept at it. We had to. Either that or we lugged a tripod around with us, which wasn’t always an option.

Which is all preface to a larger issue – the digital age’s fetish for large aperture lenses. Like most fetishes, it can’t be justified rationally. It makes no sense. In the digital age, when hyper ISO is a reality (10,000 ISO being common), there simply is no need for them. None, other than to pimp the one-trick pony that is ‘bokeh,’ which, to my eyes, is the single worst visual affectation brought about by digital capture. Suffice it to say that, as a general rule, the more you rely on bokeh to make your photographs interesting, the shittier the photographer you are. Full stop.

Back in the film era, high-speed lenses served a purpose. Most usable film stocks maxed out at 400 ASA. Tri-X and HP-5 – 400 ASA box speed films – were considered ‘fast’ films preferable for low-light handheld work. 10,000 ISO was a thing of science fiction, akin to flying cars. We learned to work within the parameters of the limitations of the technology. We became ‘photographers.’

The Noctilux: A $12000 Photographic Affectation. If You’re Rockin One of These in the Digital Age, Freud Would Say You’re Probably Insecure About the Size of Your Penis

It was these constraints that led to the production of high-speed lenses. It wasn’t for the bokeh. They were made and used for a reason – to maximize one’s ability to shoot in low light. Doing so was usually a two-fold strategy. Push your Tri-X or HP5 to 1600 ASA, and use the fastest lens – usually an f 1:1.4. If you had unlimited funds, you’d take advantage of the speed gain of the Noctilux or the Nikkor 50 1:1.2, but you usually did so only as a last measure, given the optical compromises inherent in large aperture lenses. Best bet was to learn to shoot handheld, which, with some practice, was easily doable down to 1/15th/sec with a 50mm lens and even lower with a 28mm.

*************

Given the above, I find it a delicious irony that high-speed optics are now all the rage. Were you to believe what you read on the enthusiast websites, any optic f2 or above is inferior. Serious photographers rock big aperture lenses. The irony, of course, is that we no longer need them. Lower light? Just jack up the ISO. Understanding this, and fighting the ‘common knowledge’ that says you need a Noctilux allows you the use of generally better optics, optics that just happen to be much less expensive because they’re so much cheaper to produce. You can buy the VC 35mm 1:2.5, a super sharp, contrasty modern lens if there ever was one, for $300; or you can buy the optically inferior VC 35mm 1:1.2 for 4 times the price. Your choice. Using an M10, it won’t make any difference in terms of low light ability. None. What the 2.5 will give you is sharper photos, all at 1/4th the price. Hell, it even has decent bokeh.

Views: 1530

I tend to agree.

I find superfast lenses virtually unusable when shot wide open. Even my Zeiss C Sonar at f/1.5 has slither thin DOF and limited use, but by f/2 it’s delightful and probably my favourite lens on a digital M. Couple of links below.

http://www.keithlaban.co.uk/Car_Corfu.jpg

http://www.keithlaban.co.uk/Quince.jpg

By Leica standards it is also delightfully inexpensive.

Yeah, but they [super fast lenses] look super sexy hanging off of your M10.

I don’t understand the rationale…fast lens, heavy optic cancels any advantage of holding the camera steady to prevent blur when used in low illumination natural or artificial light.

Back when most photos were reproduced in print, the limiting factor was the quality of the halftone on newsprint. If it was reproduced in a glossy publication, things were a bit better, but your image was only as good as the reproduction process. You needed to make prints in a darkroom to really show what these lenses were capable of rendering.

We though we were hot stuff shooting with a 1.4 lens. It was fast enough for low light photography, not too heavy and produced good images.

I get good results pushing Delta 400 to EI 800 and using my M-Rokkor 40mm f/2.0 lens. It weighs about 4 oz., sharp as a tack and gives me a nice, light portable kit with mounted on my M2 or Leitz-Minolta CL.

Here’s my work: flickr.com/photos/dcastelli9574/

its always been my understanding that the only thing these things are good for is for super shallow depth of field, which is kind of appealing for portraits, etc. Having one of these and spending 10k for a leitz version and using it at anything less than wide open is kind of silly, it seems to me, regardless of how much sharper they might get at smaller apertures. That being said, one of my favorite lenses is a vintage zeiss 50mm 1.5 sonnar ( i have a few iterations including a non-coated prewar version) all in contax mount. They are much sharper wide open than the nikon 1.4’s of the same era and have very shallow depth of field.

As far as using them in the digital age, the shallow depth of field feature can best be exploited by using modern cameras, digital or otherwise, which feature ultra high shutter speeds, unless you use ND filters, which is kind of inconvenient.

Yes, I noticed quickly that digital cameras had much higher speeds available than did the film cameras I was used to in my day, 1/2000 sec was as fast as my Nikons went – I think! I write think, because I seldom went over 1/500 sec. Latterly, I used Kodachrome a lot…

I like the tonality you get in your posted pictures here, but then again, I usually do. Today’s are no exception to the general rule.

However, I can’t agree with you about DOF/bokeh being some visual cop out, and nada mas; for starters, they are not the same thing and vary, lens to lens. I never owned anything faster than f1.8 in my life, and often wish that I could afford to go for one of those f1 babies. But I can’t. Period; end of my wish!

Indeed, one sometimes used faster optics in order to shoot in poor light, but certainly not always. As with focal lengths, they were chosen not only for their usual purposes. Wides were usually chosen for including more in cramped spaces, for example – but also in generously proportioned studios to create perspective effects that have often featured as definitive moments in fashion photography: during the 60s many of us shot half-length pix of models with a 35mm (on 135 cameras) in order to elongate heads at the height or corner of the frame; sounds less than pretty today, but was novel and commercially productive in the era.

Folks often use 300mm lengths to shoot the same shot today – Hans Feurer always did – and that produces its own handwriting that, if used well, becomes both personal trademark and damned effective as a photographic technique for isolating subject from background, if not wheat from chaff.

As with so much, different people need different things from the same tools, and it’s rash to generalise.

🙂

I hear you, I shoot f2.8 @1/30 ,1/15 all the time hand holding my M3. I actually like a bit of shake / haze at that speed.

In my rush to comment, I forgot to compliment you on the series of photos you posted. Nice tonality, a bit of mystery…reminds me of the work of Walker Evans during his FSA tenure. An empty space can be as much alive as a plaza full of people.

Thank you, Dan. I’ll take that as a compliment….although I could also think myself merely derivative of Walker Evans, which I could do with some truth, as he’s probably the photographer who’s influenced me the most. I grew up admiring his ‘simple’ documentary photographs and always considered him the standard to which I aspired, although I haven’t really thought much of him in years. His spartan simplicity obviously has been bred into me by long familiarity.

It’s interesting you’ve noticed the influence. I am, as we speak, reading Let U Now Praise Famous Men by James Agee with photos by Evans. A remarkable book. One of those books that everyone “is familiar with” but no-one has ever read. Agee is an amazing writer, and it’s an engrossing subject. I recommend it to anyone interested in documentary.

You’re most welcome. It’s a sincere observation.

I’ve just spend some time revisiting Margaret Bourke-White & Charles Sheeler’s work on pre WW2 industrial America. I did begin my adventure in photography with 4×5 format. Too formal & slow for me. That was in 1970.

I like fast lenses- but you know that.You have two that I worked on. I have an insane number of lenses F1.5 and faster, from a custom-converted 1934 5cm F1.5 Sonnar through to the 7Artisans 50/1.1. The latter: inexpensive, with the size and weight savings of a Sonnar. I bought two, one for the M9 and the second optimized for a deep yellow filter on the M Monochrom.

[url=https://flic.kr/p/2drxRKv][img]https://live.staticflickr.com/4893/46234101991_ce64118ebb_b.jpg[/img][/url][url=https://flic.kr/p/2drxRKv]G1016955[/url] by [url=https://www.flickr.com/photos/90768661@N02/]fiftyonepointsix[/url], on Flickr

Remember the old “Shoot Black Bears in Caves at Midnight” saying of the sixties? The M Monochrom and an F1.1 lens will do it.

[url=https://flic.kr/p/2c3J3n2][img]https://live.staticflickr.com/1957/45319452635_5c7b72a126_o.jpg[/img][/url][url=https://flic.kr/p/2c3J3n2]L1005693-Edit[/url] by [url=https://www.flickr.com/photos/90768661@N02/]fiftyonepointsix[/url], on Flickr

On the Nokton- I ended up using 1 layer of copper tape to get the focus “spot-on” at F1.1. Most of my lenses are optimized for wide-open use, those for the M Monochrom have a slightly thicker shim to account for focus shift with deep color filters. In the old days, photographers would bring their camera and new lens to a local technician to have “Zeroed”. These days- almost no one does this. The real myth is that all cameras and lenses are exactly calibrated to a standard and all will work with each other out of the box.