By Teju Cole. Reprinted from The Guardian 2/24/2020

Where can one find temporary help in this hectic world? People go on retreats, join religions, cushion themselves in headphones or lose themselves in novels. We counter the rush-hour stampede with a walk in the park, and against the public squall of political debate we set the private consolation of poetry. In an age of mayhem, everyone needs ballast and, for most people, I would guess, that ballast is made of several different things. Near the top of my personal list: photobooks. I take a photobook off the shelf and spend 20 or 30 minutes with it, and this brief immersion provisionally repairs the world.

It might be a book I’ve already looked at many times – which is even better. I’m not talking about simply looking at photographs. There are photos everywhere, and most of them are like empty calories. Many photos, even good ones, tend simply to show you what something looks like. But if you sequence several of them, in a book, say, or in an exhibition, you see not only what something looks like but how someone looks. A sequence of photographs testifies to a photographer’s visual thinking, a way of seeing revealed through choices of color, subject, scale and perspective. The photographs encountered in an exhibition might be beautiful new prints or vintage ones imbued with the aura of originality. But there are disadvantages to exhibitions: they can be noisy and crowded, open during inconvenient hours and have closing dates. With a book, though, the images and the photographer’s arrangement of them are yours for all time.

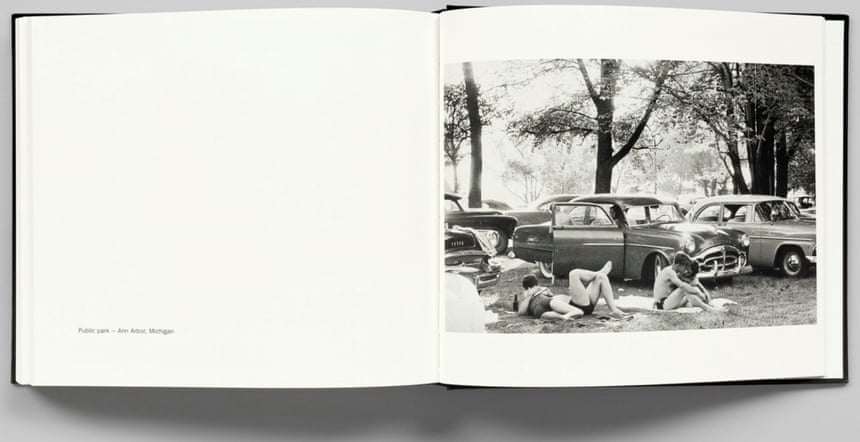

The photobook was born, by one account, when Anna Atkins made an album of her cyanotype studies of British algae in 1843. Henry Fox Talbot began to issue The Pencil of Nature, with tipped-in calotype images, the following year. It did not take other photographers long to seize on commercially distributing their photography in book form. The middle of the 20th century saw the publications of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s The Decisive Moment (1952) and Robert Frank’s The Americans (1958), and those two books, in strikingly different ways, became the looming influence against which almost all subsequent photobooks were measured. Even today, ask photographers what sent them down their chosen path and one or both of those books is likely to be mentioned as exemplars. The strength of the individual pictures is central to the success of a photobook (The Americans, like The Decisive Moment, is almost nothing but winners), but there are photographers of genius who have never made a truly great photobook; at best, they have made books of their great photos, which is a different matter.

*************

What makes a photobook great is how well it combines a large number of variables: the paper; print quality; stitching and binding; the weight, color and texture of the cover; the design and layout of the interior; the size and color balance of the images; the decision to use gatefolds or to print across the gutter; the choice to include or exclude text and, if so, how much of it, where in the book, and in what font; the trim size and heft of the book; even the smell of the ink! Every great photobook is a granary of decisions, an invitation into the realm of the senses. If a poem is great, I’m indifferent to the design choices made for the book in which it is published, unless the design is particularly atrocious. But I can tell whether a photobook has been meticulously made, or is merely a pile of pictures printed one after another. Truth be told, not all photographs in a photobook need to be great, and the real artists of the form know how to aerate their stupendous images with less forceful transitional ones.

But what a joy it is when all of those decisions seem right, when the print quality is meticulous, when a book crying out for matte paper is made with matte paper, when the color profile favors magenta over yellow, or cyan over magenta, depending on what the pictures need. The experience becomes multidimensional, and the memory of the work becomes idiosyncratically specific. I think not only of certain photographers’ styles, but also of the tactile and sensory trace of their books. The luxuriously uncut double pages of Rinko Kawauchi’s Illuminance are as much a thrill to the hands as her glimmering images are to the eye. Liz Johnson Artur’s self-titled book has a flawless combination of color images with those in black and white, the better to convey the effervescent generosity of her vision. The stippled deep purple cover of Gueorgui Pinkhassov’s Sightwalk is a braille-like prophecy of the delirious scatter of light within. These qualities are more enduring than whether a project is “important” or not. Investigative reports are important, but in our intimate moments it is sensibility that best restores us to our human selves. This is not to downplay the ethical dimension of photography, but to suggest that the ethical flourishes best when the formal conditions are in place to protect it.

*************

Of all the elements that make a photobook truly special, the most important is the order of the images. Look at this, the photographer says, then look at this, then look at this one. All books are chronological, but the feeling of being guided, of being simultaneously surprised and satisfied, is particularly intense in photobooks. I think of Masahisa Fukase’s legendary Ravens (1986), which is largely about the titular birds. It is gloomy, making great use of blur and nocturnal shooting, with a black and white palette, and set entirely in Japan. I thought about Ravens a lot when I was preparing Fernweh, though my book is superficially very different: set in the Swiss landscape, shot mostly in clear bright color in summer weather. I was aided by the way Fukase looked and looked again at the ravens, finding remarkable new ways to think about those unsettling birds. In one magical sequence, an image of a congress of ravens in the snow is followed by one of a single wing against a white field, followed by a photo of numerous corvid footprints on a lightly snowy surface, the footprints startlingly like the shapes of the birds themselves. And so, black on white was followed by black on white, which was followed by black on white – a virtuoso display of analogical thinking. This is language without words. Elsewhere, among many pictures of ravens, a sinister-looking cat suddenly appears and then a nude sex worker, and later an almost abstract closeup of a plane in flight. The trust in variation is wonderful. I tried to keep that trust in mind in making Fernweh.

In a world of deafening images, the quiet consolations of photobooks doom them to a small, and sometimes tiny, audience. They are expensive to make and rarely recoup their costs. In this way, they are a quixotic affront to the calculations of the market. The evidence of a few bestsellers notwithstanding, the most common fate of photobooks is oblivion. But it is precisely this labor-intensive and financially unsound character that allows them to sit patiently on our shelves like oracles. Then one day, someone takes one of them off the shelf and is mesmerized by the silent and unanticipated intensity. (The experience of reading a novel, by contrast, is not so silent, for the reader is accompanied by the unvocalized chatter of the text.)

Thanks Tim…

A great little guest essay, and one that has given me some new books to mull over. Along with another anticipated work from some bloke in North Carolina 🙂

My confidence in photobooks has been somewhat flat, following the acquisition of a seemingly endless succession of the not so good. The only one of which I will mention, being “Oxford” by Martin Parr, who used to be great, then ironic, but now apparently, innit for the money.

I share your disillusion with some of the stuff masquerading as monograph or similar. Perhaps we as individuals are just experiencing the same realities that face photobook publishers: they don’t want to produce such books because they don’t usually generate money, and when they do produce them, we sometimes buy and end up wishing we had not. Publishers probably knew this would happen before we did, but feel that they have to have a place at the table just to remain relevant. It makes sense that they would go with a famous name rather than with an unknown, however remarkable his pix may be: fame sells.

And even fame is no guarantee. I have an Annie Leibovitz that cost around a hundred euros and I’d sell it for twenty just to make more space on my limited shelves. I can’t bear to look at it; it’s like a reminder of my own lack of defence against impulse buying.

I note your remarks about Martin Parr; unlike you, I never did enjoy his work, feeling that he was far too vitriolic in his treatment of the lives of the great British unwashed. Of course, he is probably correct in his assessments, which might possibly explain Brexit (sorry – irresistible!). That said, industrial poverty is one terrible place in which to find oneself stranded, especially if education lets you see exactly where you are. It would be a saving mercy if those people simply had no idea about the way they live and the paucity of alternative opportunity open to them. (On the other hand, perhaps it explains the betting shops and pubs: many eyes may, after all, be wide open but helpless. ) Apart from that, I simply hated his flash photography style and especially his colour work.

I certainly don’t see myself as downtrodden, but I do have a flutter on Euromillions every week, and for five euros I get the chance twice a week to join the ranks of those who win – and some always do win – but since this pandemic came to play, the lottery has been suspended, and with it all my dreams of a graceful life that lets me travel wherever I want to travel without calculating how that would affect my liquidity. I don’t seek “things” at all, having far too much clutter in my life already: I just want the ability to come and go whenever and wherever the mood takes me. The feeling that time is running out doesn’t help very much. Time certainly accelerates as you get old. This is a well-known fact. Ask any astronomer.

I feel this post began with a couple of points in mind, but I think they may have become diverted in the journey to now. Well, I didn’t enjoy my lunch, so what can anyone expect?

🙂

You are right Rob, “vitriolic” is a far better choice than my rather wishy washy use of the word “ironic”, and I accept your correction. My first introduction to Parr’s work though was a feature in one of those old Sunday supplements of the abandoned Morris Minors in Ireland. I thought that they were rather good, it was the first time that I consciously noticed photography. The Morris Minor being (saving perhaps the Mini Minor) being the last car designed wholly by the human hand and eye.

Note that his early work was black and white (or c-41) analogue, whilst the latter is digitally manipulated computation.

In regard to your linking of Brexit to the paucity of the education of great swathes of Brits, I do not concur.

It seems to me that this lack has far more to do with the legacy of Thatcher’s horrific concept of the “core curriculum”, or “what” to think rather than “how” to think. The former being a manifest act of socialism, and the latter being an expression of conservatism.

This, despite the titular ‘CON’servative label that she applied to herself and her odious CONservative Party, which is no more conservative than the old Labour Party, that division being more regional than ideological.

The idea that education should only be connected to a grinding life of slave labour, rather than the flexibility to adjust and adapt to the ever changing world is banal, to say the least.

The traditional way in which this was done, was to teach apparently useless subjects, like Latin, ancient Greek and rhetoric, the point of which is not necessarily to use them, but to apply them to future problems.

Unfortunately, more than one generation of children have been instructed how to use a utilitarian product such as Microsoft Office, those who now, like a nasty pimply rash populate the corridors of power.

The only thing that you need to know about digital computers is that they slavishly do very simple things much faster than the analogue human brain, which operates on a quantum basis, particularly if that brain is trained in the how, rather than the what.

For those that have been taught how to think, rather than what to think, the profoundly (small c) conservative “Brexit” is instinctive. It leads to local people thinking about their history, by doing this, they (wittingly or not) preserve those conditions for our children, it is very much about the future, rather than the reactionary label that it has been tarred with by the socialists.

The surest way to lose the how, is to slavishly hand 90% of our effort to a socialist state (any of the many varieties) to splurge mainly on the current generation to the extent that it runs out of the wherewithal, cannot get away with taking yet more from the current generation without war, so steals from and rapes the future generations, merely in order to maintain that seat at the high table.

It then conceals its avariciousness by presenting conservatives as racists, xenophobes and more recently islamophobes… haters, if you like. In fact it is the socialist who hates not only the current generation, but the historical generations and those that have yet to be.

On the contrary, our country and the countries that have adopted those conservative values (that which is pink on the older maps) have been absorbing people of every race and creed throughout history. It was too cold and wet for any human being to survive here, (especially Scotchland) :-). Hence since the recession of the last ice age, we are ALL immigrants to these shores.

The conservative should ask one thing, that new people need to adopt our secular ways, and place the word of god beneath the practical settlement achieved through the application and acceptance of common law.

By all means persist in your Judaism, Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism or Islamism privately. Form local clubs and associations, use those traditions and apply them to your new, adopted situation. Such clubs (or little platoons) can apply their rules locally and to some very specific disciplines, such as religion, art, gardening, crafting, sport… the list goes on, and allow us to use our own money and time to invest in our local territory, regardless of how long we have been there and ensure that it endures.

That is oikophilia.

The alternative socialist (and its many varieties from menshivism to nazism), approach is to kill and hate everything that their current particular variety deems to be unclean. Socialism has led to more than two hundred million premature deaths during the last century, and does not look like going away any time soon.

The latter forms (corporatism, fascism or nazism) are hated by the socialists even more than conservatism, since they try to link socialism to territory, which is both risky and dangerous. They prefer their utilitarian globalism as it disposes of the tedious conservative values of home, history, nature and beauty, and all of those “useless things” that teach us so much.

The fastest way to make an impact on the socialist evil, is to starve it of our economic effort, to ignore its demands for funds to support whatever current rights of special interest they choose to employ. Hence the long march through the traditional (organically grown) institutions, comparatively quick to destroy, yet with nothing other than slavish obedience at the point of a gun, to paper over it.

Topically, the current confection known as “covid”, is being used by the state as a one of the increasingly regular and more obvious (to me) power grabs. It is going to lead to less anonimity, more taxes, more hidden inflation (QE and other such tools), more justification for the suspension of the fundamental rights of freedom, liberty and the pursuit of human happiness. all three of which are wholly derived from localist self government.

Sorry to say this Rob, but your apparent devotion to the globalist loving EU apparatchik declarations of freedom of movement, destruction of borders, free movement of captial and the precautionary principal, is merely “shilling” imposed by avaricious, power hungry criminals.

Resistance of such spivvish tricksterism has not and has never precluded the invocations of any of those freedoms, which can be arrived at through settlement by negotiation, co-operation and equitable agreement.

—————————————-

Who knew that a superficial analysis of the dross produced by Martin Parr, could be as polemic as the simple consumption of a madeleine turned out to be?

Stephen, you really should avoid the madeleine or, if you can’t resist it, have some better coffee with it. It obviously upsets your system. Personally speaking, I prefer meringues.

When my wife and our parents were alive, she and I used to drive periodically over to Scotland and spend six weeks going back and forth between the two houses. One of the main highlights – apart from Waterstones’ bookshops – was going into Marks & Sparks and buying meringues and chocolate éclairs to take home for elevenses or tea, depending on time of day. I used to have quite a sweet tooth. Today, I take no milk or sugar in tea – actually, I almost never have tea anymore but prefer a mug of hot water. Coffee still gets milk, but no sugar.

🙂

My preferred coffee is mostly Ethiopian and processed by the “natural” method. Such coffee is brought to the processor by hundreds of smallholders, often with as few as a dozen plants.

Unfortunately it is not in season at the moment, so I am ordering other African coffees. except Kenyan. My recent brews have been made from Rwandan, Burundi and DRC, beans, and again, they are mostly “naturals”. South or central American coffee is usually washed, apart from the occasional Guatamalan effort, and way too clean, all I get from most of them is acid. Possibly a contender for producing the caffeic acid that caffenol brewers rave over.

My Londinium lever espresso machine is on a timer, switches on at 5:00 am and switches off at 10:30 am after which, coffee is verboten.

Never consciously had a madeleine, don’t eat biscuits or anything else made from wheat… As you say meringues are a delightful sweet, although I am more partial to dates and “Snickers”.

I occasionally have a slice of toast from oats that the wiff gets from the “Wheat Free Bakery” from your manor in Scotland. Sainsbury provides my favourite butter, which is made from whey and is delightfully salty… No jams, marmalades, honey or nut butters, they bring me out in hives. My favourite sweet flavour is dark amber maple syrup.

But as you say Rob, water, hot or cold (but not icy) is a wonderful lube, for maintaining “regularity”. The occasional cup of builders, from Yorkshire sometimes gets a chance to be processed by me, strong and with a tiny amount of milk just to change the colour and add a little fat.

I don’t consume anything that might ferment in my disease ridden gut, so no alcohol, which is great shame since I really used to like Timothy Taylors and that one from Cornwall, ah yes… Doom Bar. Spirits are best used to power the car, or clean the needle on the record player.

And lastly Bob Dylan, rasping away at “When I paint my Masterpiece”, on countless different occasions, usually with different words, represents my continuing hope… though “Sailing round the world in a dirty gondola”, is looking more and more like a thing of the past.

His wailing encouages me to keep trying to produce something that is both personal and pleasing.

In the meantime, we will just have to look forward to praying to the analogue gods, here via Tim’s inspirational organ.

I wouldn’t argue with Teju Cole.

That said, I am not totally convinced that sequence in a book matters a lot other than in the case of two photographs appearing on opposite pages where the look of each image, its weight/internal dynamics, makes or breaks the overall look of the combination. You face the same situation when you hang two photos close together on a wall. Or try to balance two jugs on a shelf on a kitchen dresser. Of course, if the book is supposed to be telling a sequence-dependent type of story, that’s another matter.

My books on Saul Leiter don’t strike me as having any particular order to them in their structure – I look at each one and enjoy it for what I think each image in them to be. I think photo books work best when there is a picture on the right-hand page and a minimum of text on the left page.

However, there is no doubt that photography, for me, became what it became because of the printed pages of magazines and much less so because of books. As a kid, I had no access to galleries – I doubt that perhaps outside of New York any existed for photography back then – and perhaps that was not such a bad thing: it didn’t confuse my mind with photography as a lifestyle being possible through the art world rather than the commercial: no ivory towers beckoned, and no thoughts of being the bearer of important messages. I just wanted to make photographs because I loved them, and to get paid for the pleasure at the same time. That simple wish turned out to come loaded with a heap of practical difficulties and contradictions, I can promise you! I’m amazed it worked out as it did, and I’m still not sure exactly why I got lucky – other than that I threw my hat into the ring and believed in myself.

Ciao.

Teju Cole… Charlie Hedbo… ’nuff said,

Care to elaborate?

I really like what Cole writes about photography, but yes, his stance re: the Hebdo attacks is disgusting. He brings to mind Knut Hamsen, Nobel Prize winning author who wrote the sublime Growth of the Soil..but was also an unrepentant Nazi. Enough said from my end.

On the contrary: not enough said from your end! Write on whatever topic you please, but write. It brightens my day when I see a new thread on your site. And this has nothing to do with lockdown, either, which has had limited effect on my life other than forcing me to cook, which I can’t, and today I reached a point where a simple plate of pasta and tomato sauce had me wanting to push my plate away a third into the meal, which was perhaps not the fault of the meal, but okay, not the same damn thing three times a week. Oh, I also miss walking by the sea and dropping into a bar somewhere for a coffee. Simple things we take for granted until the unexpected day when we can’t.

Rob