Which One Do You Prefer?

“Digital capture quietly but definitively severed the optical connection with reality, that physical relationship between the object photographed and the image that differentiated lens-made imagery and defined our understanding of photography for 160 years. The digital sensor replaced to optical record of light with a computational process that substitutes a calculated reconstruction using only one third of the available photons. That’s right, two thirds of the digital image is interpolated by the processor in the conversion from RAW to JPG or TIF. It’s reality but not as we know it… Veteran digital commentator Kevin Connor says, “The definition of computational photography is still evolving, but I like to think of it as a shift from using a camera as a picture-making device to using it as a data-collecting device.”

I ran across the above quote in an article in Time Magazine entitled “The Next Revolution in Photography Is Coming,” which, to put it charitably, is normally not the first place I look when I want cutting edge philosophical discussions, given its pedestrian readership usually located on the far end of any cultural curve. Nevertheless, it’s an interesting article, discussing things some of us, myself included, have been articulating since the inception of the digital age. Just a few years ago, saying essentially the same thing on a popular photo forum, I was roundly derided as a kook by the usual suspects. It’s not as if ignorance and lack of expansive thinking don’t have a consistent pedigree; if history teaches anything, it’s that the revolutionary implications of technological changes are never seen by the average guy until they’re impossible to ignore. Now, if Time is any indication, maybe it’s a message finally resonating with the generally educated public: the passage from analogue to digital “photography”, from a philosophical and practical perspective, is less an evolution than a revolution of the medium. What we’ve wrought, with our CMOS and CCD sensors that transform light into an insubstantial pattern of 1’s and 0’s, is not merely a difference of degree from traditional photography but rather a fundamental difference of kind. You can even make a claim that digital photography really isn’t ‘photography’ in the etymological sense of the word at all. As Mr. Connor suggests, its more accurately described as “data collecting.”

Until recently, photography worked like this: light reflected off people and things and would filter through a camera and physically transform a tangible thing, an emulsion of some sort. This emulsion was contained on, or in, some physical substrate, like tin, or glass, or celluloid or plastic. The photograph was a tangible thing, created by light and engraved with a material trace of something that existed in real time and space. That’s how “photography” got its name: “writing with light”.

Roland Barthes, the French linguist, literary theorist and philosopher, wrote a book about this indexical quality of photography called Camera Lucida. Its one of the seminal texts in the philosophy of photography, which means it’s often referred to while seldom being read, and even less so, understood. To summarize Barthes, what makes a photograph special is its uncanny indexical relationship with what we perceive “out there,” with what’s real. And its indexical nature is closely tied to its analogue processes. Analogue photography transcribes – “writes”- light as a physical texture on a physical substrate in an indexical relationship of thing to image (i.e. a sign that is linked to its object by an actual connection or real relation irrespective of interpretation). What’s important for Barthes’ purposes is that the analogue photograph was literally an emanation of a referent; from a real body, over there, proceeded radiations which ultimately touched the film in my camera, over here, and a new, physical thing, a tintype, or daguerreotype, or a film negative, was created, physically inscribed by the light that touched it.

Now photography is digital, and the evolution from film to digital is not merely about of the obsolescence of film as the standard photographic medium; rather, it’s the story of a deep ontological and phenomenological shift that is transforming the way we capture and store images that purport to copy the world. Where we used to have cameras that used light to etch a negative, we now have, in the words of Kevin Connor, digital data-collecting devices that don’t “write with light,” but rather which translate light into discrete number patterns which aren’t indexical and can be instantiated intangibly i.e. what is produced isn’t a ‘thing’ but only a pattern which contains the potential of something else, something else that requires the intercession of of third thing, computation.

*************

The First Photograph, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, 1827, Le Gras, France

The First Photograph, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, 1827, Le Gras, France

In August, 2003, I was sitting in the garden outside of Joseph Niépce’s Burgundy estate, where, from the window of which, Niépce had taken history’s first photograph. I was enjoying a pleasant late Summer afternoon in the company of George Fèvre, one of the unsung masters of 20th Century photography. A personal friend of Henri Cartier-Bresson, George was the master printer at PICTO in Paris and was the guy who printed HCB’s negatives from the 1950’s until HCB’s death in 2004. If you’ve seen an HCB or Joseph Koudelka print on exhibit somewhere, in all likelihood George printed it.

George was an incredibly nice man, humble to a fault, full of fascinating stories about the foibles of the photographic masters and very thoughtful about the craft of photography.

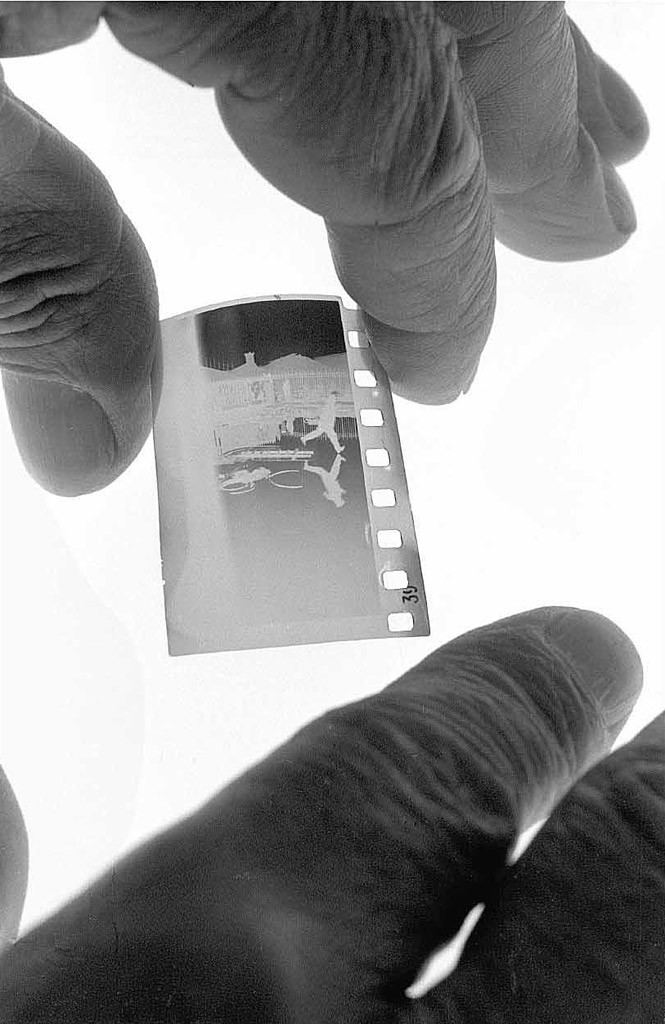

HENRI CARTIER-BRESSON, Behind the Gare St. Lazare (1932). Picto Labs, Paris. Hands: George Fèvre, Paris 5/11/87 © John Loengard

HENRI CARTIER-BRESSON, Behind the Gare St. Lazare (1932). Picto Labs, Paris. Hands: George Fèvre, Paris 5/11/87 © John Loengard

Up to that day I lived in the old familiar world of traditional photographic practices: aperture and shutter, exposure, film type, developer characteristics, contrast filters and paper grades, a world whose highest achievements George had helped promulgate. What better person to talk to about photography, and what better place to do it, where it all started.

Of course, I wanted to hear his stories, first person accounts of iconic photographers and their iconic prints, and George, always the gentleman, obliged without any sense of the significance of what he was remembering. To him, the specifics of how HCB or Koudelka worked, the quality of their negatives, and how George used them to create the stunning prints that made them famous were nothing special, all in a day’s work for him. What George was interested in talking about was Photoshop, something he had just discovered and of which he was fascinated. And he said something curious to me, something I always remembered and something I stored in memory for a better time to reflect on it.

What George said was this: Photoshop was amazing. Anyone could now do with a few keystrokes what he had laboriously done at such cost in the darkroom. It was going to open up the craft in ways heretofore unimagined. But it was no longer photography. There was something disquieting about the transformation. Photography’s tight bond with reality had been broken, its “indexical” nature, as Barthe would put it, had been severed, and it was this bond that gave photography its power. We were arriving at a post-photographic era, where image capture would become another form of graphic arts, its products cut free from ultimate claims to truth. There could be no claims to truthful reproduction because there was nothing written and no bedrock thing produced, just a numerical patter of 1’s and 0’s instantiated nowhere and capable of endless manipulation. The future would be the era of “visual imaging.”

Since that day, the cataract of digital innovation has not abated but intensified— we all know the litany because we are caught up in it on every side: 36 mp DSLRs with facial recognition and a bevy of simulations, camera phones, Lyto, Tumblr, Facebook — do I need to go on?

George Fèvre, Le Gras, France, August, 2003

George Fèvre, Le Gras, France, August, 2003

The changes have brought their benefits: giving people the chance at uncensored expression, allowing us to easily capture and disseminate what we claim to be our experiences. Of course, there are also new problems of craft and aesthetic. Previous technologies have usually expanded technical mastery, but digital technology is contracting it. The eloquence of a single jewel like 5×7 contact print has turned into the un-nuanced vulgarity of 30 x 40 tack sharp Giclee prints taken with fully automated digitized devices and reworked in Photoshop so as destroy any indexical relationship with the real.

We are currently living through a profound cultural transformation at the hands of techno-visionaries with no real investment in photography as a practice. All the more ironic in that this has happened at a time when popular culture now bludgeons us with imagery: while photography is dead, images are everywhere. You see imaging on your way to work, while you’re at work, at lunch time, on your way home from work, when you go out in the evening. Your computerized news feed and email inbox is full of it. Even what you read has become an adjunct to the primacy of the image. The problem is that the images digital processes give us possess no intrinsic proof of their truth, its non-instantiated computated product endlessly malleable and thus cut free from ultimate claims to truth. And it’s this claim to truth that gives photography its uncanny ability to communicate with us, to make us reflect, or to aid us in remembrance, or to help us see anew.

Views: 3295

Pierre Gassmann and Peter Turnley at PICTO, 1983

Pierre Gassmann and Peter Turnley at PICTO, 1983 A famous negative. Those are George Fevre’s fingers.

A famous negative. Those are George Fevre’s fingers.