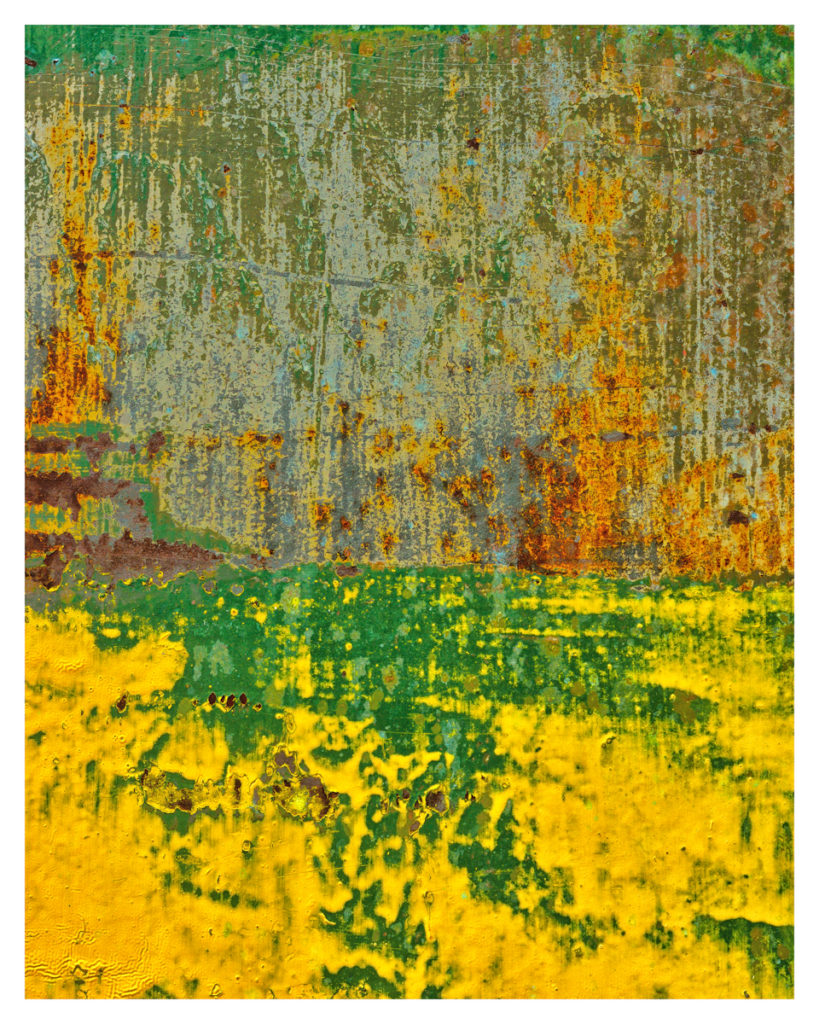

Untitled, 2005, (20×30 Acrylic on Canvas)

Above is a painting I did in 2005. It’s previously been exhibited in an ‘Art Gallery’ in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, which means the gallery owner thought it appropriate to consider as ‘Art.’ Now, irrespective of what you think of the painting and my skills as a painter, chances are you don’t find it unusual that it’s considered ‘Art’ and was offered as a work of ‘Art’ by a gallery that’s in the business of selling such things. Putting aside critical valuation, we agree that a painting is a work of ‘Art.’ I took a blank canvas, took various pigments, and using a brush I made something, a thing, physically created by me from an aesthetic idea I had in my mind. Voila! Art.

Using those same criteria, photography as an ‘Art’ form can be problematic. Photography (still and moving) is a different sort of a creative medium. It has its subjective element – what’s within the frame will always depend on someone’s choice and interpretation – but generally we consider it objective, objective in the sense that it’s a mechanical reproduction of an existing set of visual phenomena. The second characteristic – its status as an objective reproduction, a truthful documentation, the fact that it’s a mechanical means to more or less faithfully record whats “out there”, is seemingly what prevents many otherwise broad-minded people from considering it ‘Art.’

The argument- Is photography ‘Art?’ – is as old as the medium itself. Early photographers naively thought to claim it as ‘Art’ by selectively photographing “scenic” things, thus mimicking the ‘artistic’ treatment of traditional subjects of representational painting – a more exacting form of landscape painting, where the goal was fidelity to the real. Later photographers, like Alfred Steiglitz, founder of the Photo-Secessionist movement, sought to claim it as ‘Art’ by rejecting the larger definition of Art and placing it on equal footing with other forms of expression commonly considered as Art:

“Photography is not an art. Neither is painting, nor sculpture, literature or music. They are only different media for the individual to express his aesthetic feelings… You do not have to be a painter or a sculptor to be an artist. You may be a shoemaker. You may be creative as such. And, if so, you are a greater artist than the majority of the painters whose work is shown in the art galleries of today.”

This doublespeak, of course, is just another way of claiming its status as an art form without using the loaded word itself, to my mind ample evidence that, deep down, even Steiglitz himself felt a wee bit self-conscious about claiming photography to be ‘Art.’ Much has happened since Steiglitz’s era. From an institutional perspective, photography has been presented in American art galleries and art museums since the 1970’s, when “post-modernist” photographers like Friedlander, Winogrand, Arbus and Eggleston, among others, became recognized within the larger ‘Art World.’

*************

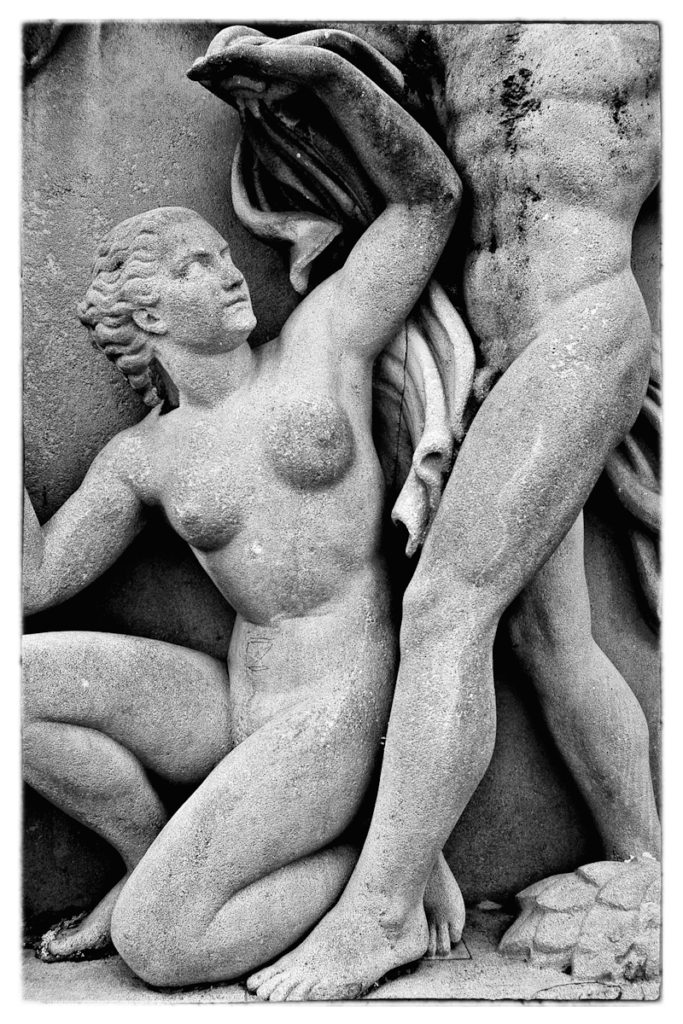

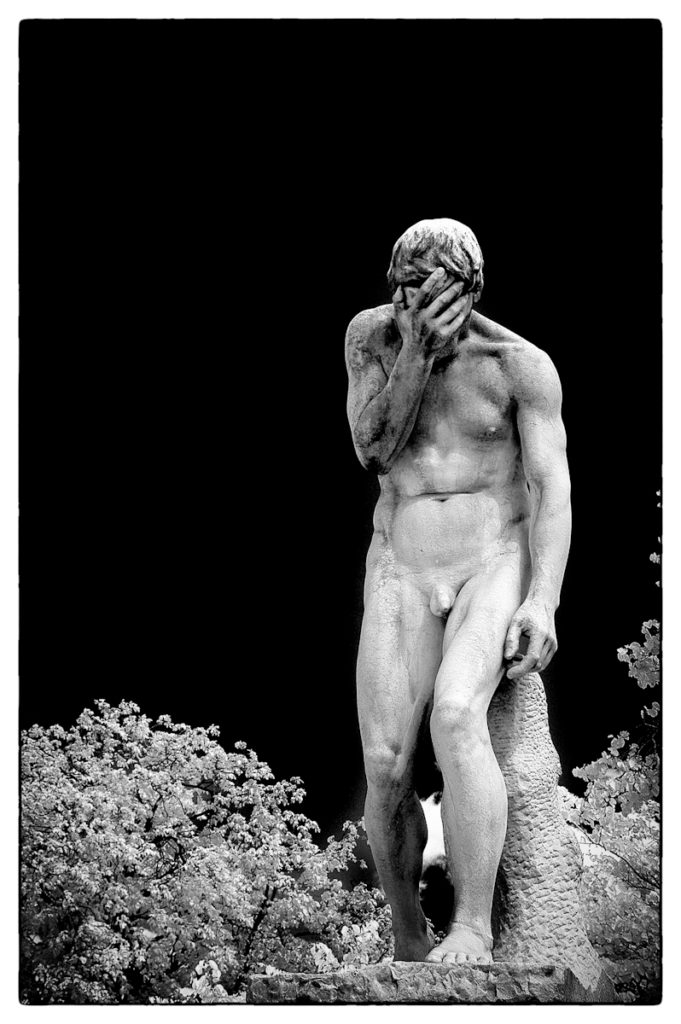

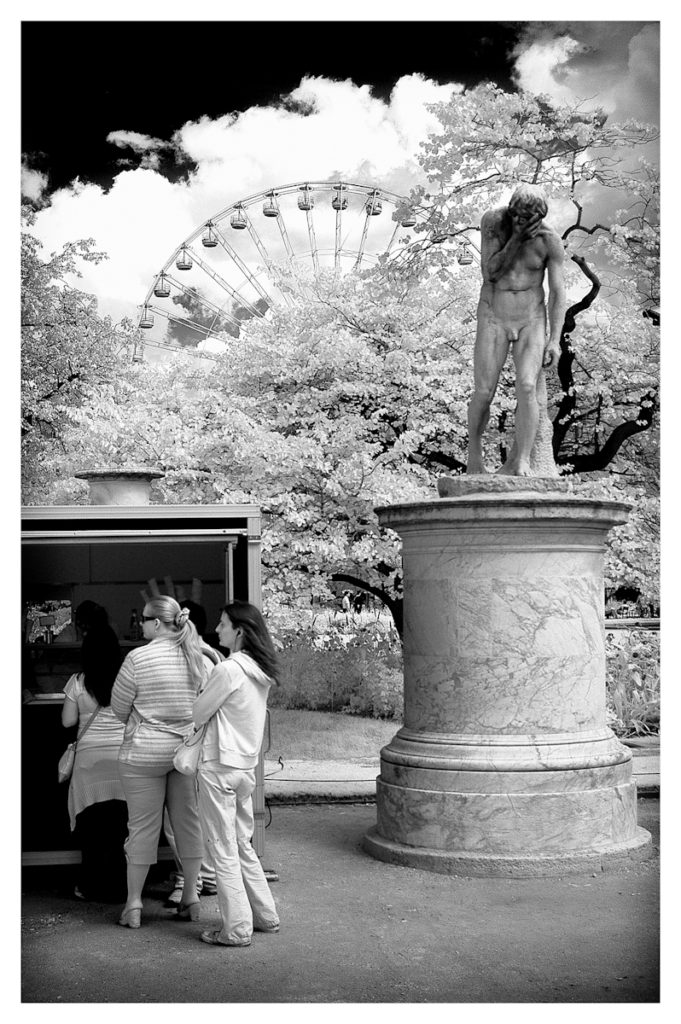

Whatever the official Art World line, from a lay perspective there continues to be a common-sense resistance to claim photography as ‘Art.’ Even I, who’s been involved with photography as a creative medium for most of my life, cringe when a photographer bills him or herself as an “artist”, and I’d like to explore the philosophical underpinnings of that discomfort. I suspect it has something to do with the “handedness” we associate with Art, the requirement of creating some ex nihilo, something unique and new. A precondition of ‘Art’ is that the Artist physically make it, physically impose form on undifferentiated material, whether that material be words or tones or rock or canvas. In photography, you could argue, we’re not doing that; instead we’re recording something already existent, something whose creation resides elsewhere. I’ve touched on this subject before in a piece entitled Formalism and Photography (Can Photos of Statutes Be Art?).

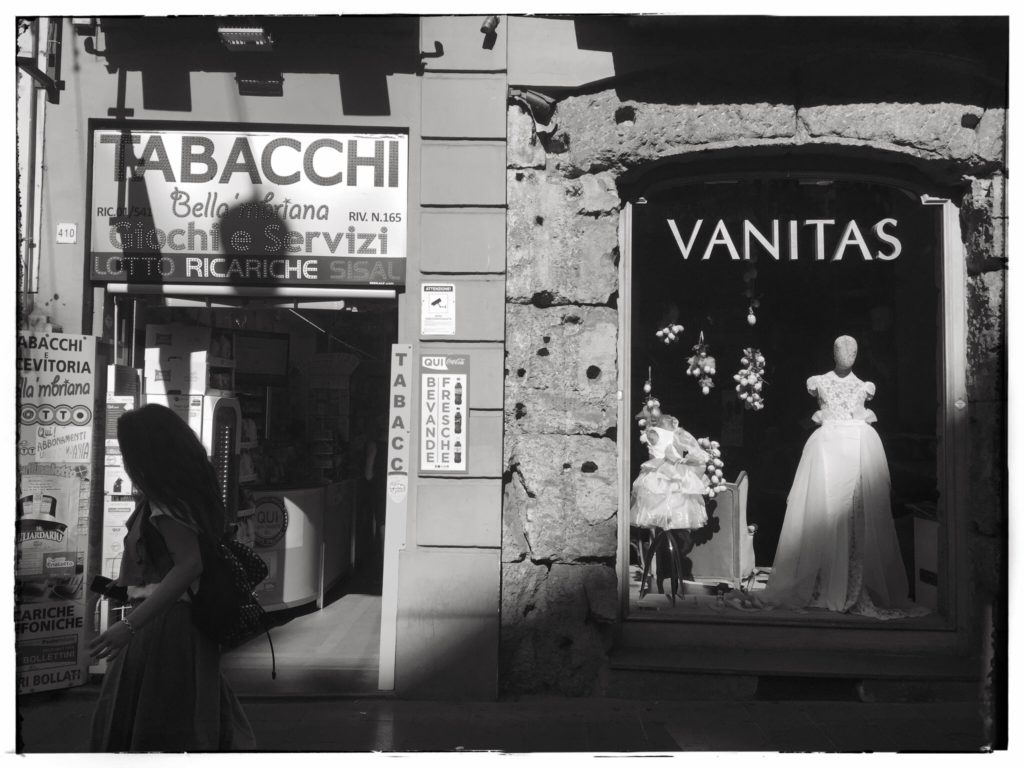

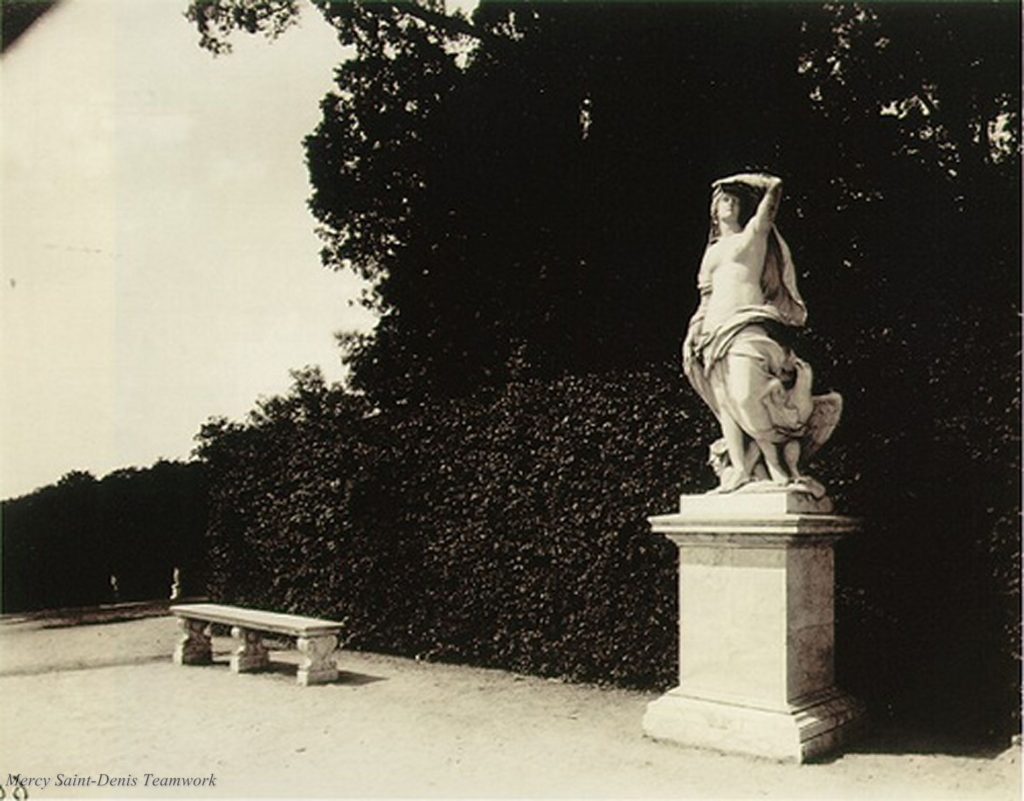

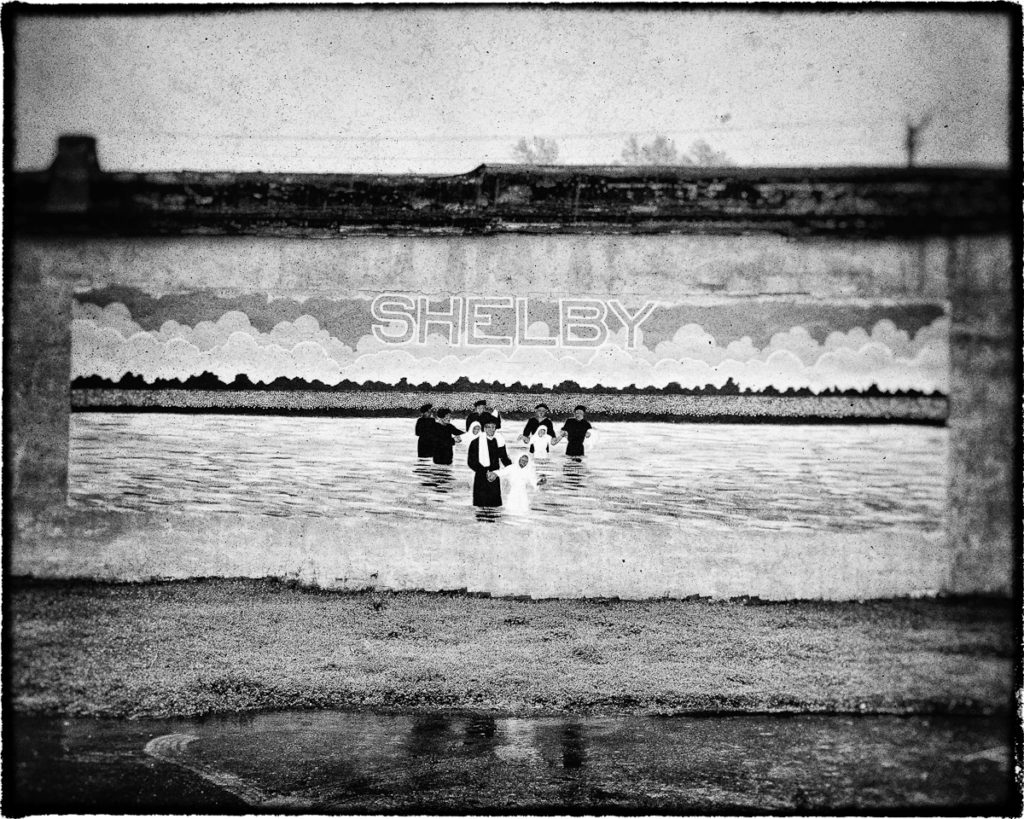

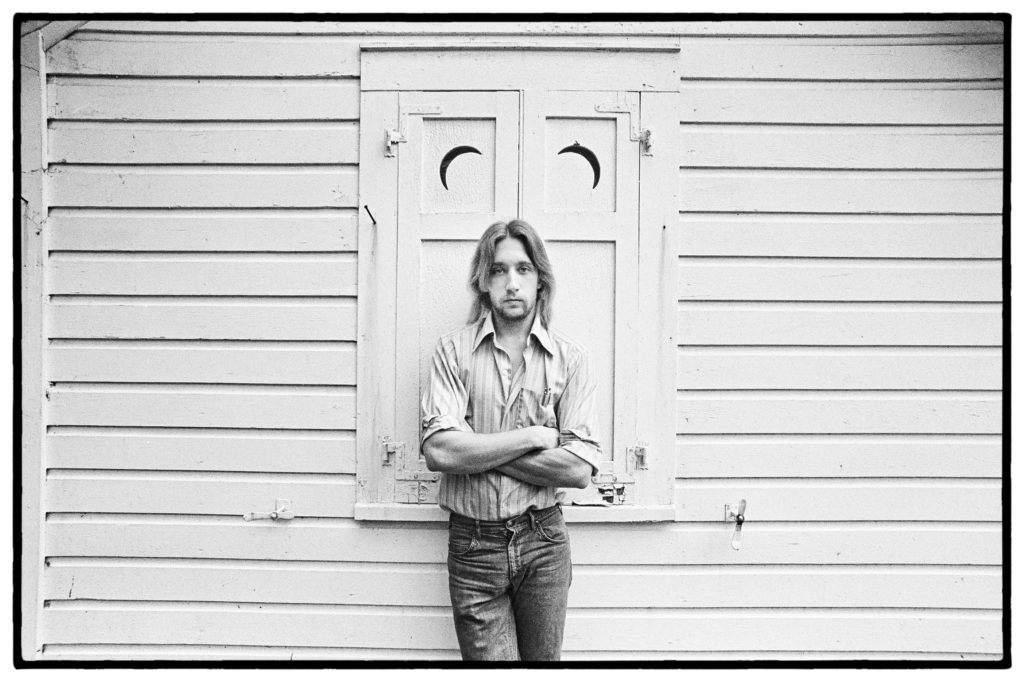

Untitled, 2016

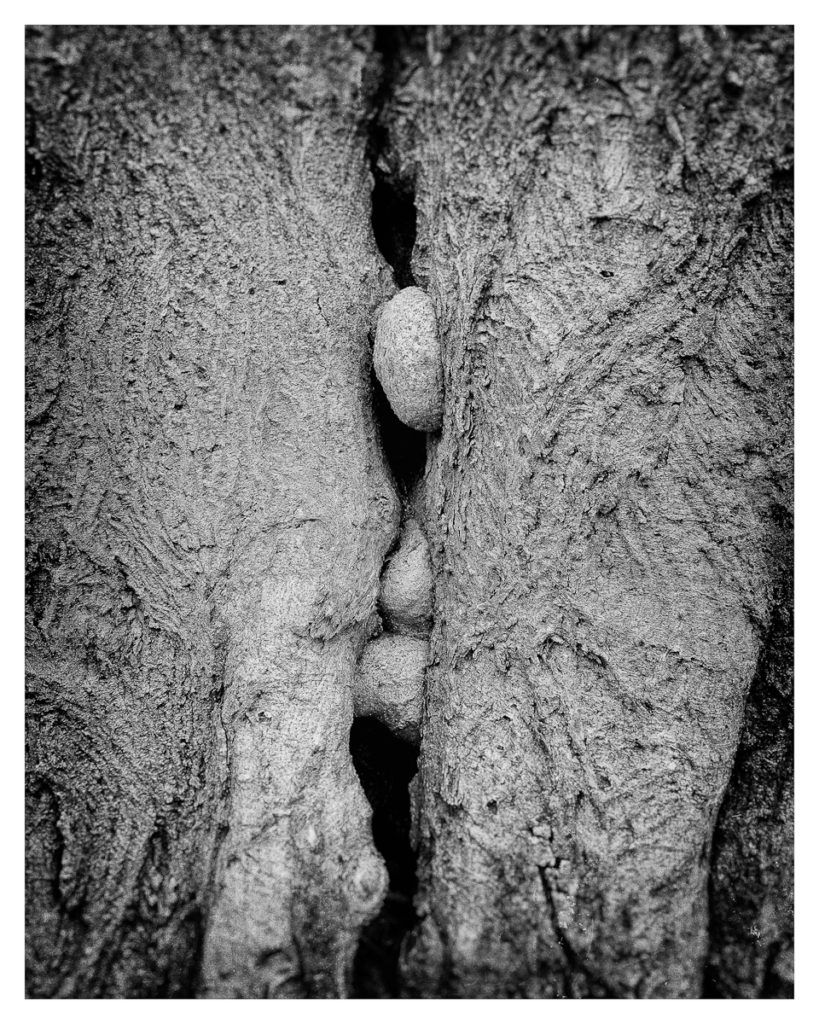

How about Untitled, 2016 above? Is it ‘Art’? It’s something I did in 2016. Formally, it’s remarkably similar to Untitled, 2005 above. Like the former, it’s “modern” in the sense that it’s not representational but rather its own aesthetic reality, created from the ground up by the artist. I consider it competently drawn, its color scheme consistent and complimentary, its pictorial elements situated in an aesthetically pleasing manner. I like it, and would be pleased to have a piece like it hanging in a conspicuous place in my home or, better yet, in someone else’s home, someone who valued it enough to purchase and exhibit it. Except, its not a painting. Its a photograph, a straight-up close-up of a section of a wall of a building recently torn down in the service of progress. What I did was merely isolate it from its larger context by photographing it and, with some very minor post-processing (contrast, saturation, sharpening etc), created the finished work you see, “created it” in the sense that a series of 1’s and 0’s now resides in a certain pattern on a hard disk on my computer. Its literal creation – how those pigments came to be in the manner they are – is an unintended consequence of building paint, weather and time.

As mentioned previously, we commonly consider a precondition of Art that the Artist physically make it, physically impose form on undifferentiated material. If this is so, then the work itself – a photograph – is problematic; have I “created” anything by simply recording it? Have I imposed form on something undifferentiated, i.e. incoherent and messy, when I photograph? Haven’t I rather just seen and selected, noted for other’s benefit as it were, something that already had a certain form, essentially simply pointing out something aesthetic that already existed, created naturally or by happenstance? Could it be the fact that I isolated the view itself be the creative act? Is that enough?

Additionally, there’s the issue of uniqueness. There’s only one of any given painting. We can reproduce it photographically, yes, but we don’t consider the reproduction to be a piece of Art. Now think about that in terms of photography. Unlike a painting, I’m able to print out my photograph in any number of sizes on any number of different media, run limited editions etc, and sell each individual print as its own work of Art. Yet, irrespective of the size or the type of medium I print it on, the underlying ‘artwork’ will be the same (or will it?). [ This has become an issue with the endless exact replicability of digital capture, as opposed to old school silver halide prints where each print is a unique individual interpretation of a negative.]

I suppose I could do the same thing with the painting i.e. photograph it and present the photographic reproduction as its own work and offer it for sale in a gallery in different sizes and on various media. Why not? Except there’s something intuitively wrong with that when we’re talking about photographic reproductions of two dimensional paintings, or so I think. What’s intuitively wrong with it are two things: first, the fact that it’s a photograph as opposed to something created ‘by hand,’ and second, that it’s not the unique created thing itself. These facts seem to change the terms of the debate.

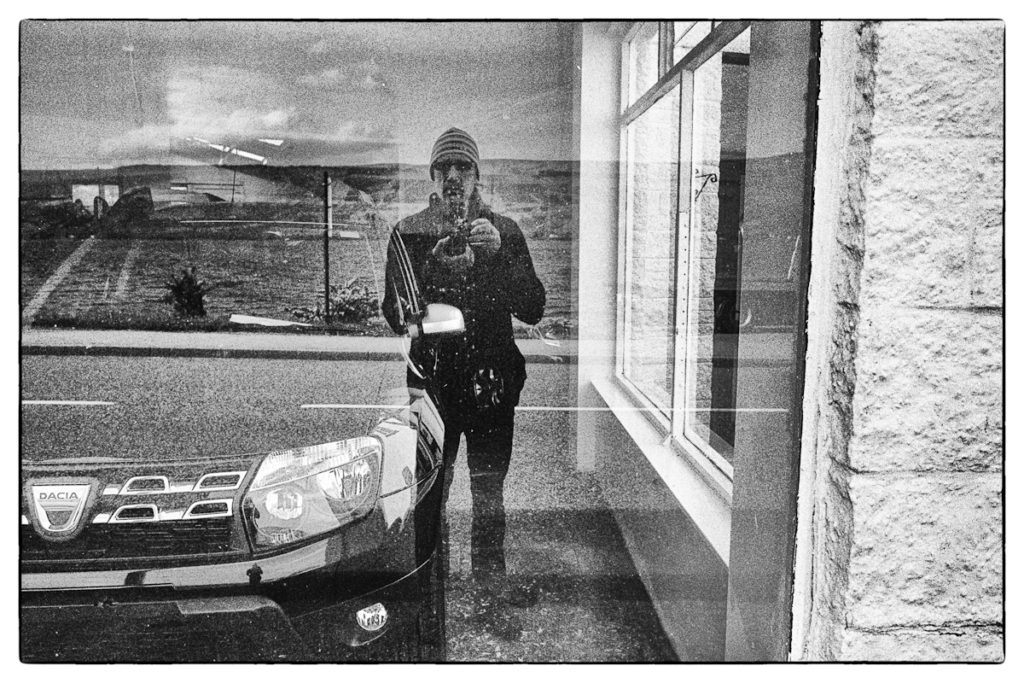

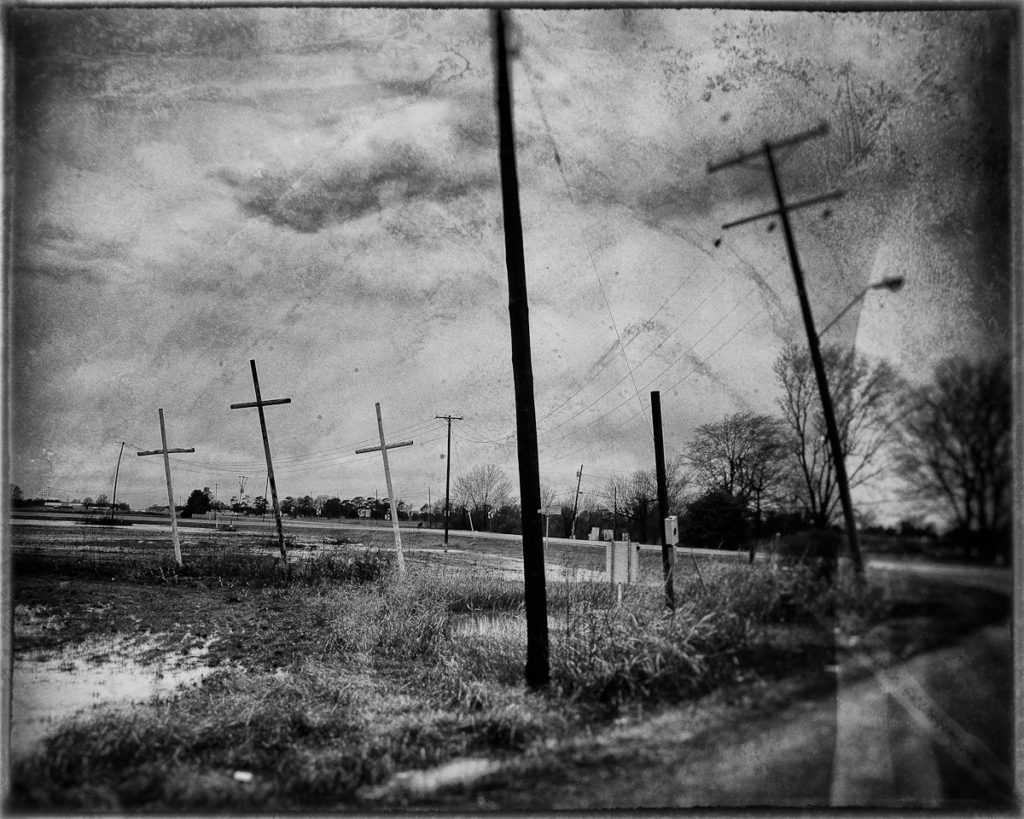

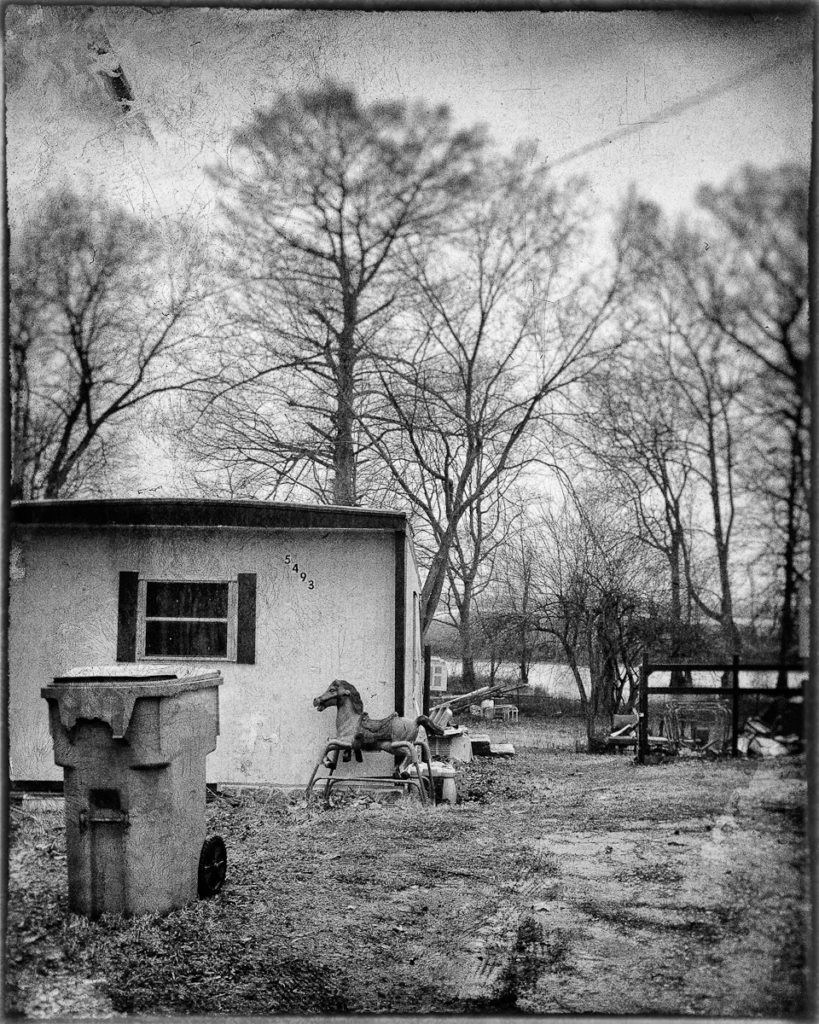

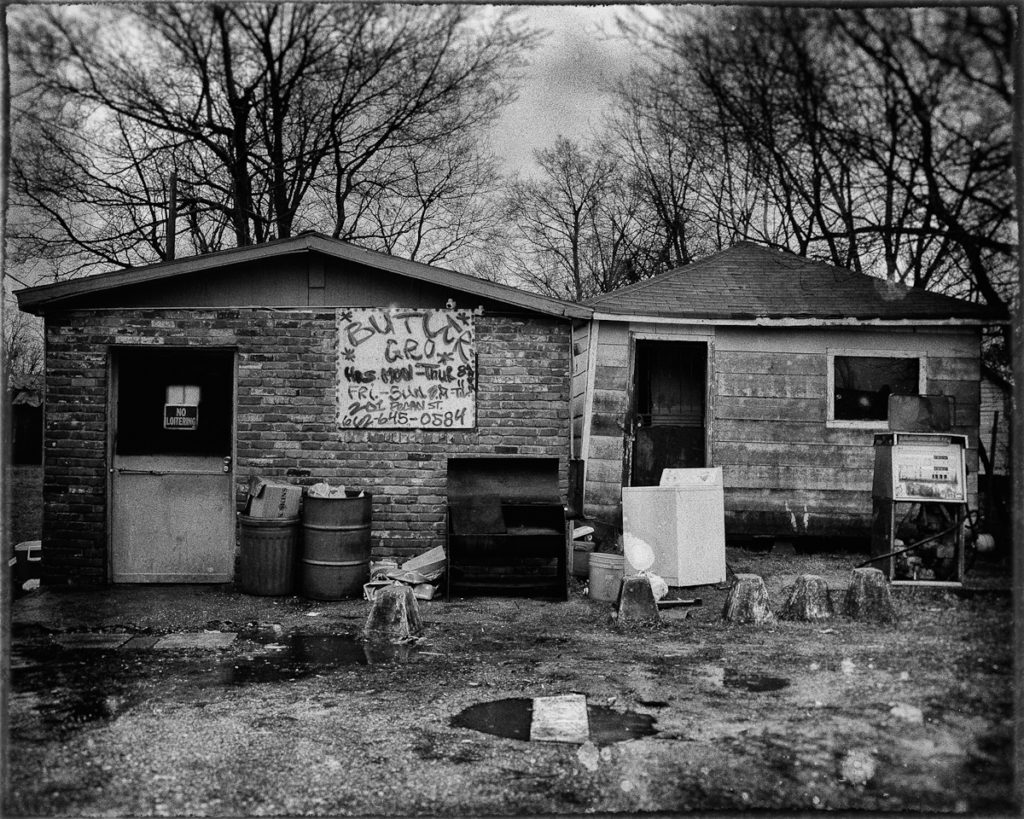

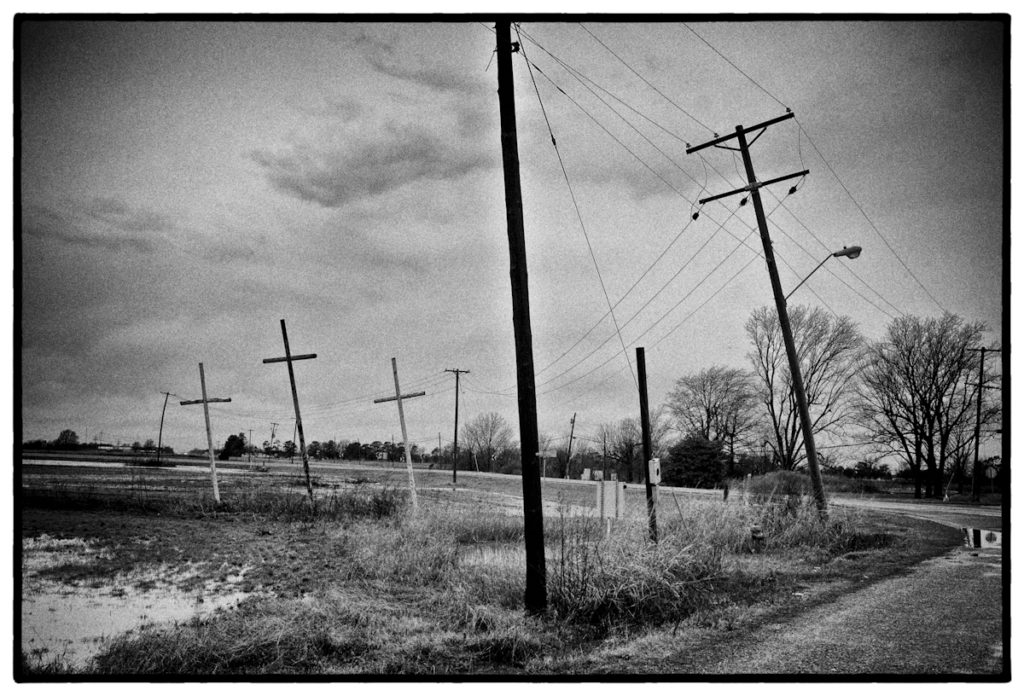

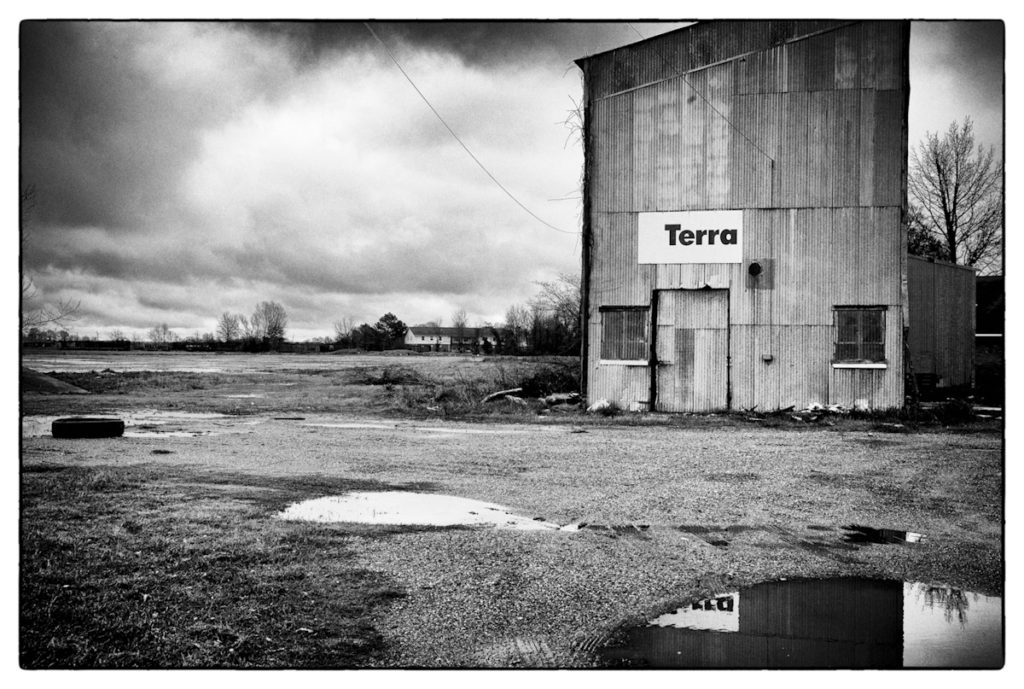

A Simple Picture I Took Out My Car Window Recently. If I Hung it in a Art Gallery and Titled it Untitled 2018 Would That Make it Art?

Of course, maybe the best response, and probably the closest to the truth, is the ” Institutional” definition of Art, somewhat cynical, that holds that ‘Art’ is whatever gets exhibited in an ‘Art Gallery’. We decide what it is simply by defining it as such. This is what Marcel Duchamp was claiming for Art when he exhibited a toilette bowl as part of an exhibition of his work in a gallery, asking his audience to look at the toilette bowl aesthetically by placing it in a context where we are, by definition, asked to do these things. Duchamp’s definition simply requires that there be an intent on the part of the artist to have what’s presented be seen in a certain way, even if the creative act is simply the presentation itself. What then, of things created without the aesthetic intention, where the intention can be understood as conveying the state of things at any given moment, like a photograph? Can Nick Ut’s My Lai photos be ‘Art’ if they’re viewed in an art gallery? How about the found photographs that Melissa Cantanese put together in her book Dive Dark Dream Slow that I’ve discussed before?

To my mind, learning to think of photography as an Art Form means first to recognize in a literal sense what a photograph is. It’s a two dimensional piece of paper with “indexical” markings on it. That’s it. That’s the most an Athenian citizen of Socrates’ time (Socrates himself, for that matter) or some primitive man pulled out of the forest in Papua, New Guinea, would be capable of seeing it as, because they’d not have the conceptual (as opposed to he intellectual) ability to do so, that conceptual ability given to us by the social, cultural and technical knowledge which we possess and which is a precondition to understanding it as something more. Without this embedded knowledge – what we take for granted – they literally couldn’t see the representational nature of the photo. They’d simply see the thing itself – the flattened 12×18 2 dimensional thing with a certain form embedded as part of it.

Somewhat paradoxically, I think it’s this two dimensional reality of photographs that opens the way to seeing them as ‘Art.’ Abstract painting only started making sense to me when I started thinking in non-representational terms, when I accepted the notion that paintings don’t need to be a transcription of anything; they can just be what they are, a thing, something with no function other than being its own reality. It’s what art historians term an understanding of the painting’s inherent “flatness.” Photos can be the same way. Forget for a second that Untitled 2016 was produced by a camera and in some sense depends on an existing visual arrangement contained somewhere “out there”; We can choose to see it as we’d see Untitled 2005. Just look at it, try to see what’s literally in front of you. Stop thinking of it as referencing something else. Just let it be itself. Analyse it in those terms. For that matter, there’s nothing keeping us from seeing Untitled 2018 in the same way…or is there?

This is the third in an ongoing series about philosophical issues and what they might have to say about photography. Part One can be found here, Part Two here.