Category Archives: analogue photography

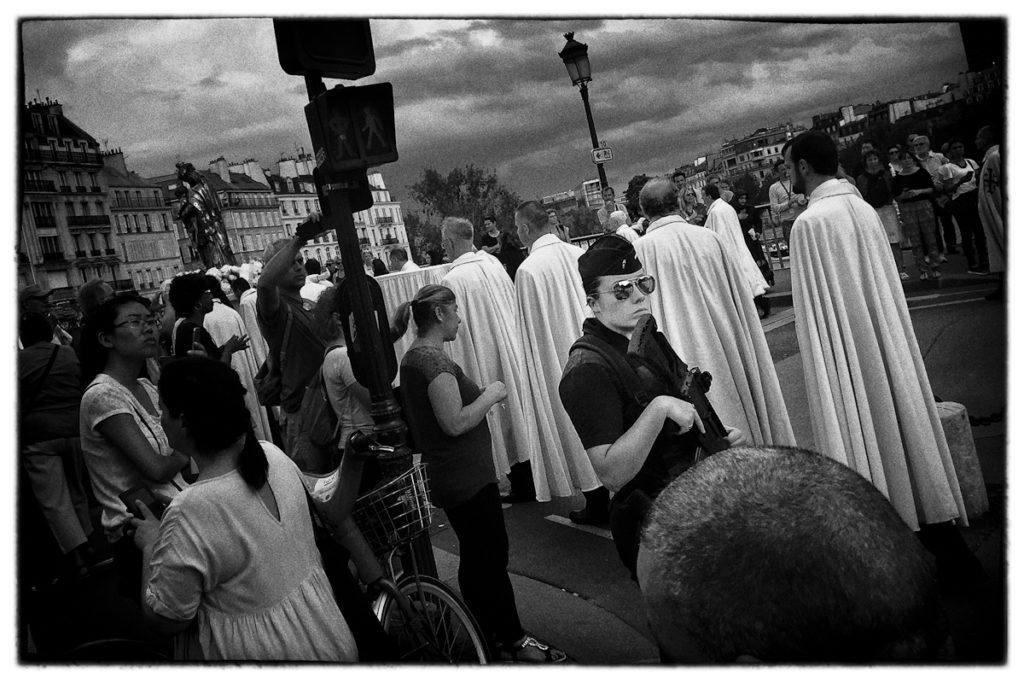

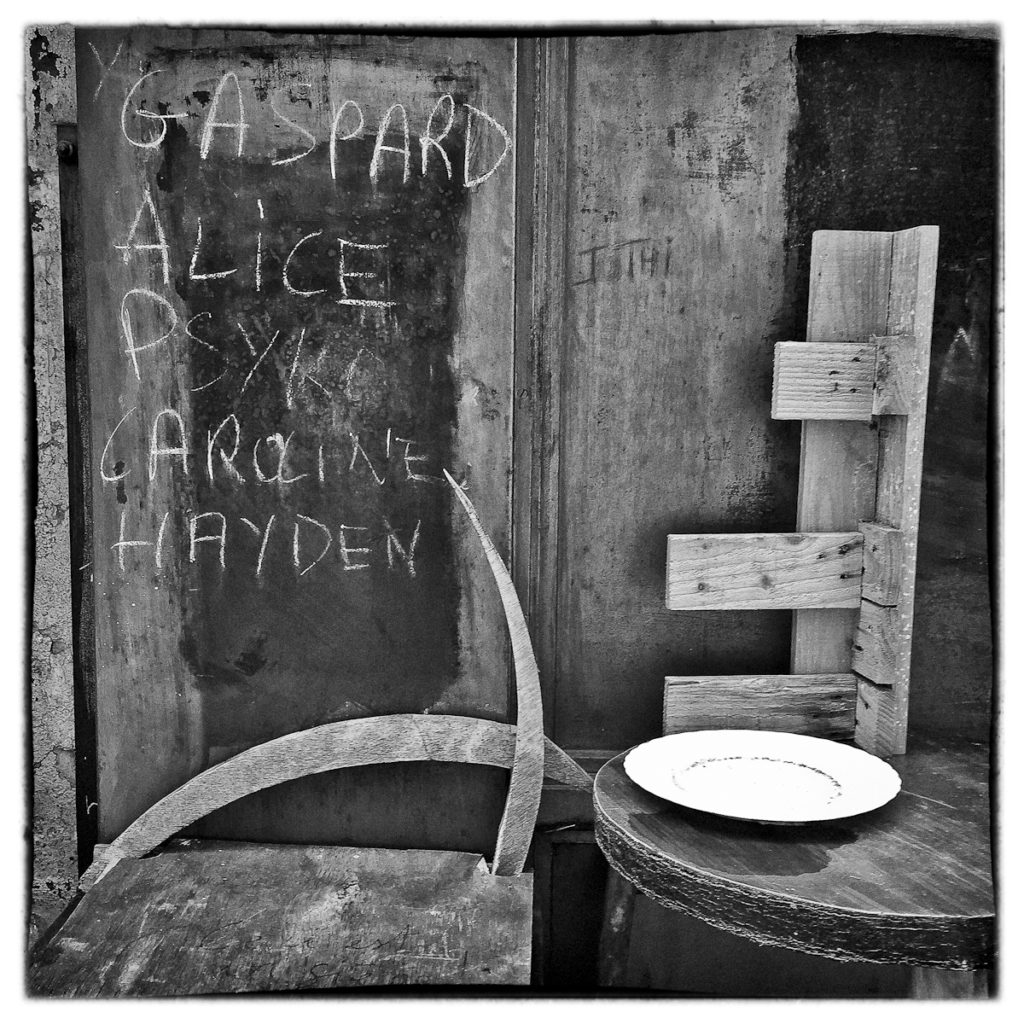

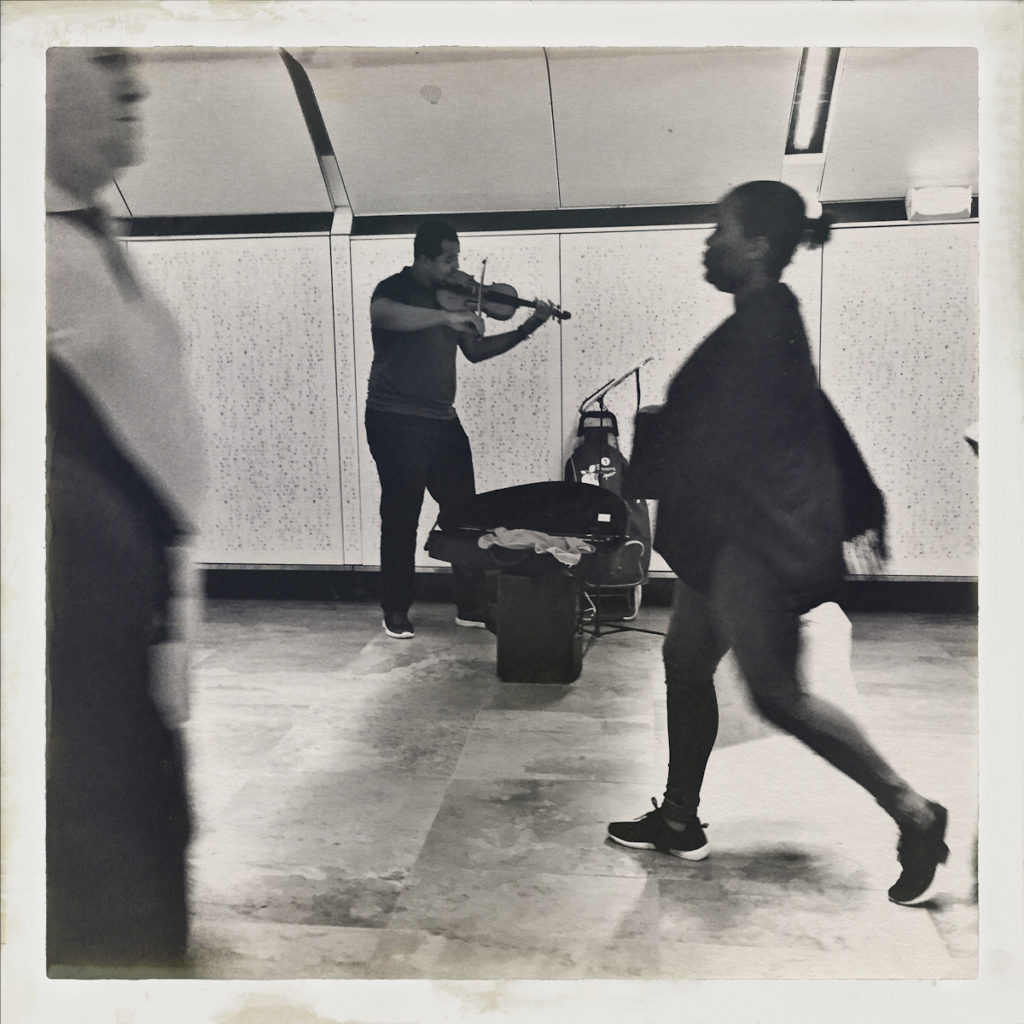

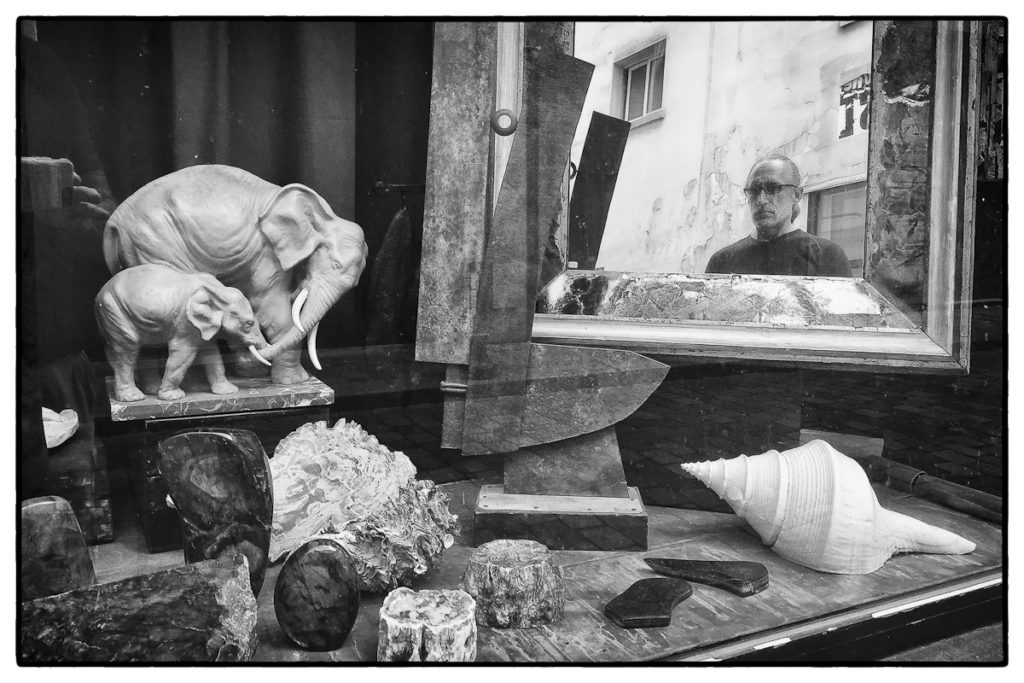

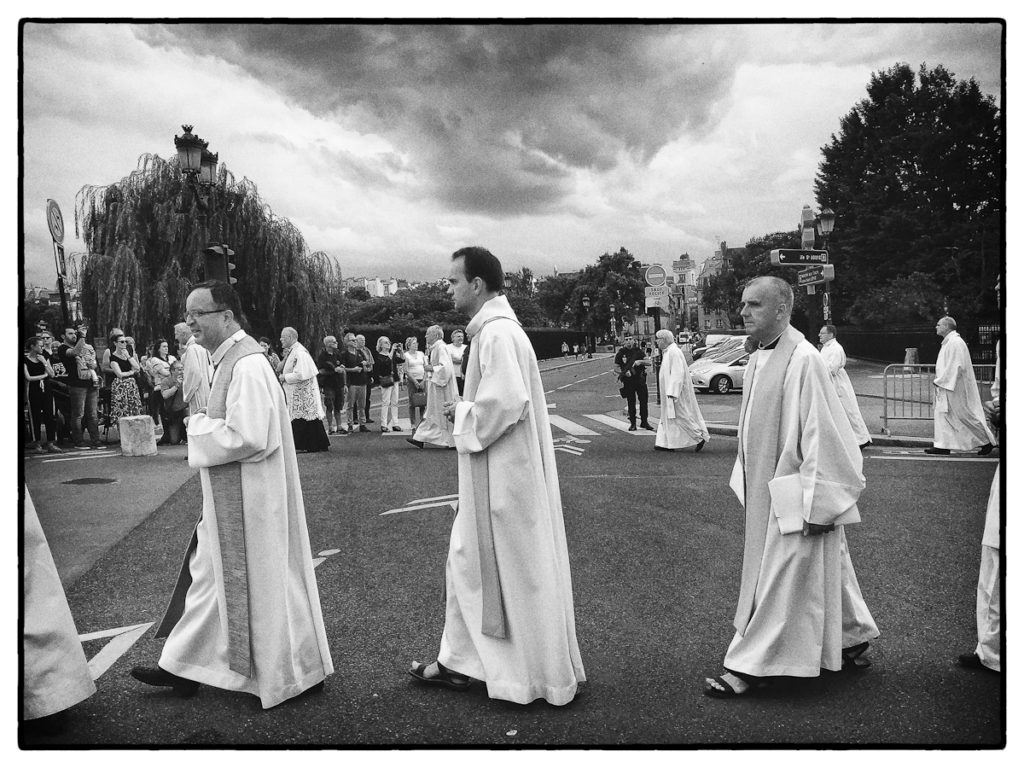

A Day in Paris

Paris, August 17, 2017

Has photography become too easy? I’m thinking it might have. The question, I guess, is, even if it has, why would that matter?

I’ve illustrated this post with photos I’d taken on one day, August 17, 2017, a day I spent chaperoning a first time visitor to Paris. The day started bright and clear, with increasing cloudiness as the morning progressed and, by afternoon, threatening rain.

I hadn’t even thought to take a camera with me. The day was just to be a day seeing the usual sights. Of course, I had my iPhone with me, and during the day, as much as habit as anything intentional, I took a few photos of things that interested me. Some were shot using filters – I presume I just chose a random filter for the hell of it – and others were post-processed in Snapseed on my phone.

Now, I’m not claiming any of these to be portfolio quality, but in reviewing them, I’m amazed at the quality and diversity of output I got with a simple camera phone and some free apps, all in a day’s walk around town. We used to expend a lot of time and energy and creative angst to get similar results back in the film era, weeks and months of hard labor both on the street and in the darkroom….and the results were indicative of a photographer possessed of technical competence and creative mastery. Back in the film era, the results below would have been the product of innumerable creative decisions about cameras and formats and films and developing and printing processes. Now, it’s indicative of a guy with some apps on his camera phone.

So, I’m not sure what argument I should be making…is this a good thing or a bad thing?

The State of Film Production 2019

Interesting presentation by the CEO of ADOX at the Finnish film fair in Helsinki, March 15, 2019, addressing the current state of film production. ADOX is one of the few remaining manufacturers committed to film production. We should be supporting them.

ADOX is the brand name the German company, Fotowerke Dr. C Schleussner GmbH of Frankfurt am Main, the world’s first photographic materials manufacturer, founded in 1860. The current rights to the ADOX name were obtained in 2003 by Fotoimpex of Berlin, Germany, a company founded in 1992 to import photographic films and papers from former eastern Europe. Fotoimpex established the ADOX Fotowerke GmbH film factory in Berlin to convert and package their films, papers and chemicals using machinery acquired from the closed AGFA (Leverkusen, Germany) and Forte Photochemical Industry (Hungary) photographic plants.

The currently constituted ADOX company has resurrected former ADOX films and AGFA films, paper and chemicals including the entire Agfa B&W chemistry line with the help of its former employees and it now holds the trademark for Rodinal film developer. Chemistry is currently produced by Calbe Chemicals, formerly a part of Agfa (OrWo).

In 2010 ADOX test- produced a slightly improved version of the original AGFA APX 400 as ADOX Pan and started full production of ADOX CHS II (100 ISO, equivalent to Efke KB 100), a black and white film using modern coating, which eventually took priority over attempts to re-introduce Agfa APX 400. In February 2015 ADOX purchased the Ilford Imaging, Switzerland (Ciba Geigy) machine E, medium scale coating line at Marly, Switzerland to coat photographic film and paper. ADOX CHS (II) was coated by ADOX in Marly from 2018. ADOX are also (2017-19) doubling the size of the film factory in Germany to add a small coating line using a former AGFA machine as well as space for small scale chemical production and film materials storage.

ADOX Products

Films:

- CMS 20 II ISO 20 An Agfa-Gevaert ortho microfilm converted by ADOX offering very high resolution, needing a special developer for contrast control. Format: 135, 120 [Editor’s Note: CMS 20 is an incredible film for large prints – high resolution with super fine grain.]

- CHS II 100 ISO The original ADOX R/KB21 film (Efke KB100 to 2012) classic 1950s ortho-panchromatic B&W print film. Introduced 2013 as a modern coating, but sold out by 2016. Due to Adox acquiring own coating line, it was not re-introduced until 2018, initially as sheet film. Format: 135, 120, Sheet film.

- Silvermax 100 ISO panchromatic B&W print film (Similar to the original Agfa APX 100). Coated at Inoviscoat. Format: 135

- SCALA 160 ISO panchromatic B&W reversal film (Same as Silvermax) Format:135

- HR-50 50 ISO Super-panchromatic ultra-fine grain – Agfa-Gevaert Aviphot 80 modified to enhance usability. May also be used as an infra-red film with suitable filtration. Introduced in 2018. Format: 135

- IR-HR PRO 50 ISO 80. Super-panchromatic fine grain film – Agfa-Gevaert Aviphot 80 as HR-50 without modification. Initial trial batch introduced 2018. Format: 135

Photographic Paper:

- MCC 110. Fibre based paper ( the Old Agfa Multicontrast Classic) emulsion made using original Agfa machinery.

- MCP 310. Premium Resin Coated photo paper with outstanding image quality ( Agfa Multicontrast Classic) emulsion made using original Agfa machinery.

- Fine Print Variotone. A newly developed warm tone paper made in cooperation with Harman Technology and Wolfgang Moersch

- Lupex. A slow speed contact fiber paper made with a silver chloride emulsion and replaces Kodak Azo or Fomalux.

Inkjet Photographic Paper:

- Art Baryta. Pure uncoated baryta base for coating with liquid emulsions

- Fibre Baryta. Inkjet paper using fiber-base from analog photo paper manufacturing (100% alpha-cellulose with a barium-sulfate coating) and is coated with an inkjet receiving layer plus a backside coating to minimize curling behavior.

- Fibre Monojet. An inkjet media optimized for the reproduction of black and white images.

Film Developers:

- RODINAL Liquid concentrate developer dating from 1891 and produced according to Agfa Leverkusen’s latest Rodinal formula from 2004

- ATOMAL 49. Powder-based Universal ultra-fine-grain developer for all types of B/W materials with good speed utilization and high compensating factor. (Development of Agfa Atomal with currently available chemistry)

- FX 39 II. Geoffry Crawleys FX-39 was a development of Willi Beutler’s formula for Neofin Red.

- Silvermax Developer. Specially formulated to increase tonal range in the Silvermax 21 film, formulated by SPUR

Paper Developers:

- ADOTOL NE. Liquid concentrate Neutral black working paper developer. Former Agfa developer

- NEUTOL WA. Liquid concentrate warm tone paper developer. Former Agfa developer

- MCC Developer. Liquid concentrate fine art developer For Multigrade Papers for neutral-black image tones. Former Agfa developer

- NEUTOL ECO. Liquid concentrate without hydroquinone based on ascorbic acid.

- ADOTOL KONSTANT Powder developer, which produces a neutral black image tone

- RA-4 Kit Liquid concentrate color paper developer kit

Other Chemicals:

- ADOSTOP ECO (2018) Liquid concentrate 100% citric acid based odorless stop bath.

- Acetic Acid 60% Acetic acid liquid concentrate for stop baths.

- ADOFIX Plus Liquid concentrate, high capacity express-fixer with a maximum capacity for black and white photo papers (RC and fiber), films and photographic plates.

- ADOFLO Highly liquid concentrated wetting agent

- ADOSTAB Liquid concentrate, image stabilizer, and wetting agent.

- SELENTONER Selenium toner for black and white photo materials (films or paper)

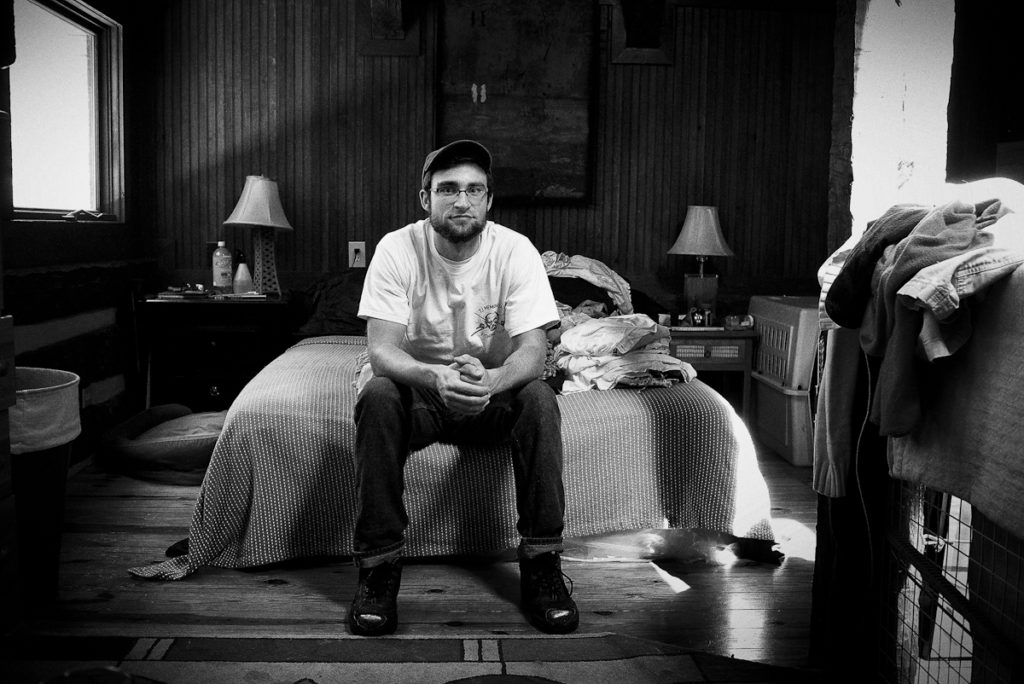

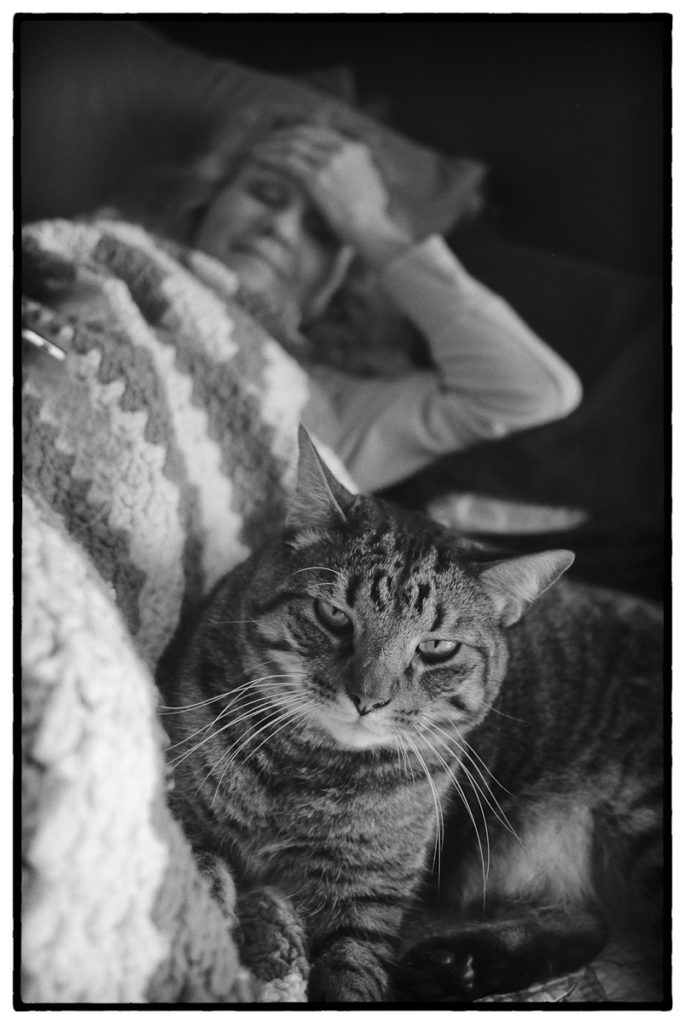

Various Creatures on My Bed

This Person Exists. Maybe.

This Woman Seems Like a Nice Person, or at Least She Looks Like One

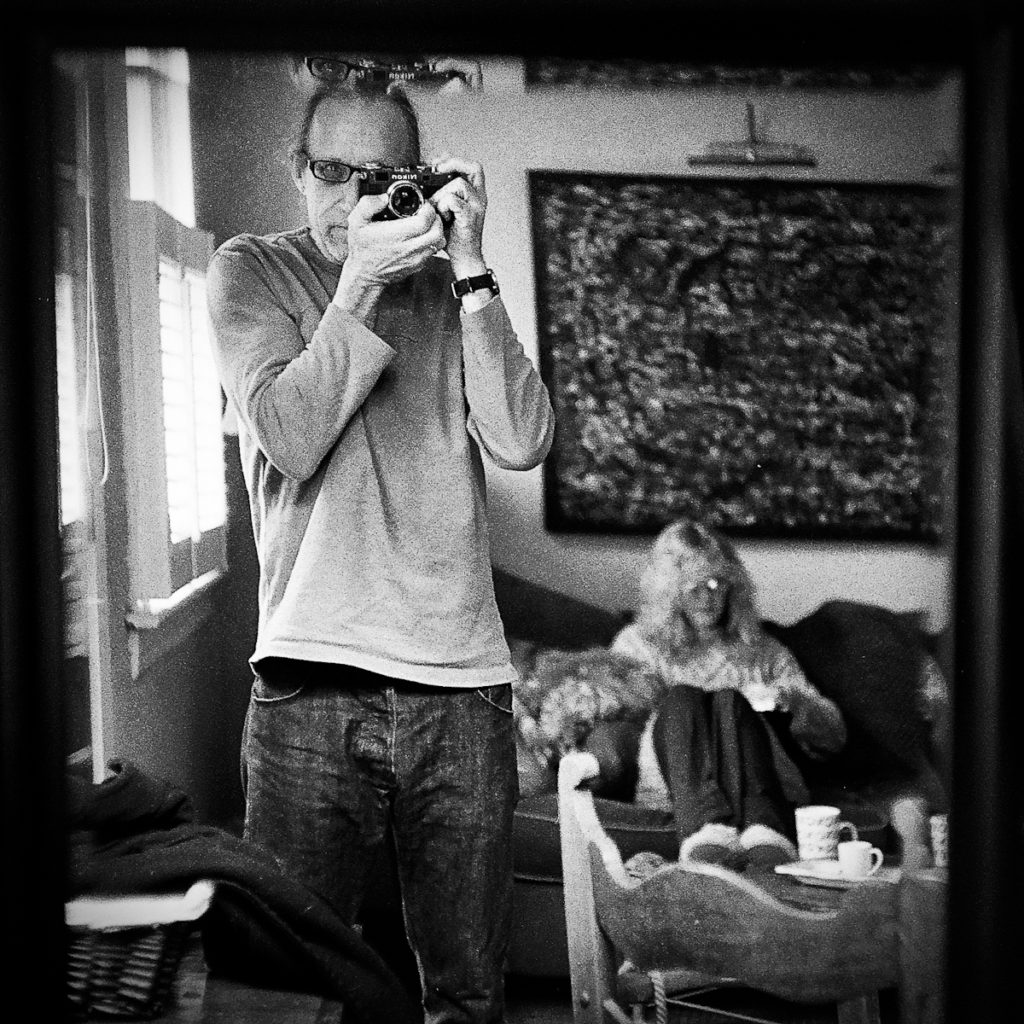

“Photographs furnish evidence,” wrote Susan Sontag in On Photography. “A photograph passes for incontrovertible proof that a given thing happened.” Sontag went on to admit that photographs might sometimes misrepresent situations, but the basic premise went unchallenged: Photos show us things that exist. It’s because of what we perceive as the photo’s truthful reliability, the “indexicality” issue we’ve beaten to death in the last post and accompanying comments. That’s a photo of me, over there; Sontag would say it’s evidence I exist. (I do.)

“Photographs furnish evidence,” wrote Susan Sontag in On Photography. “A photograph passes for incontrovertible proof that a given thing happened.” Sontag went on to admit that photographs might sometimes misrepresent situations, but the basic premise went unchallenged: Photos show us things that exist. It’s because of what we perceive as the photo’s truthful reliability, the “indexicality” issue we’ve beaten to death in the last post and accompanying comments. That’s a photo of me, over there; Sontag would say it’s evidence I exist. (I do.)

Of course, Sontag wrote in 1977, before digital photography was a thing. Now, go to the website “This Person Does Not Exist”. There you’ll see nice, unmanipulated photos of different men and women, normal looking people you’d expect to meet during your day, people just like me up there – except that the photos aren’t of real people. The people in the photos do not exist and never have existed (one of these non-existent persons is shown in the photo heading this post). Their existence has been generated via an algorithm, in this case, a “generative adversarial network” which produces original digital data [read: a new photo] from existing sets of digital data [read: 1’s and 0’s created by a digital camera]. The generative algorithm scans photos of real faces and creates new photos of new faces from them. Voila! A real photo of a fake person.

Now, take a look at that photo. If I hadn’t told you the above, if I were to tell you that was my wife, or a friend, or a family member, and that’s what she looked like, you’d believe me. All you readers arguing with me in the comments section about indexicality, you’d believe me because photos, film or digital, basically tell the truth, right? OK, it’s digital, so maybe it might have been photoshopped a bit, a few pimples removed, eyes brightened, a few crow’s feet smoothed over…but the person is real, they stood in front of someone with a digital camera, obviously they exist, and they probably look something like that. Right. You guys crack me up, unable as you are to see past the outdated conceptual blinders you wear. For those of you arguing against the idea that there really isn’t much difference between the presumed truthfulness of film versus digital photos, go to the website and look around.

*************

in 1945, film critic André Bazin (1918-58) wrote an essay entitled ‘The Ontology of the Photographic Image’. ‘Ontology’ is a word you’ll see a lot in philosophy. It’s the study of the ultimate “being” of a thing (e.g. “What do we mean when we say a thing is an animal?”). To discuss the ontological status of photography is to consider what particular kind of thing a photograph is. Kazin’s interest in the ontology of photography leads to Susan Sontag (On Photography, 1977) and Roland Barthes (Camera Lucida, 1980).

I’ve already discussed Barthes at length elsewhere. In Camera Lucida, Barthes employed a philosophical method associated with Jean-Paul Sartre called “phenomenology”, Barthes himself noting the book was written “in homage to L’Imaginaire by Jean-Paul Sartre.” Sartre wrote L’Imaginaire in 1940, a few years before Kazin’s essay, wherein he applied the ideas of Edmund Husserl, the founder of phenomenology, to investigate various kinds of images, including photographs.

Sartre’s point in L’Imaginaire is that there are different kinds of apprehending, correlated with different kinds of objects. Sartre says that when looking at photos we must “intend pictorially”; i.e. apprehending something as a picture is different from apprehending something as a simple object. “If it is simply perceived, [the photo] appears to me as a paper rectangle of quality and, with shades and clear spots distributed in a certain way. If I perceive that photograph as ‘photo of a man standing on steps’, the neutral phenomenon is necessarily already of a different structure: a different intention animates it.” That’s classic phenomenology, where every conscious experience has “intentionality,” which is a fancy way of saying that everything we think is shaped by the category we place the thing thought about.

Barthes, following Sartre, notes the difference involved in perceiving a photo versus perceiving it as a photo. For Barthes the essence of perceiving something as a photograph is ‘that-has-been’: “In photography,” he writes, “I can never deny that the thing has been there”. The person in the photo exists, Barthes is saying; the photo is the proof. By contrast, no painted portrait can compel me to believe its subject had really existed. Hence “This-has-been; for anyone who holds a photograph in his hand, here is a fundamental belief… nothing can undo unless you prove to me that the image is not a photograph.”

So, what of the analyses of Bazin, Sartre, Sontag, and Barthes in the digital age? I’ve discussed the implications of Barthes’ thought here. Listen again to what Barthes considered the ontology of photography: “This-has-been; for anyone who holds a photograph in his hand, here is a fundamental belief… nothing can unless you prove to me that the image is not a photograph.” Using this definition, a digital photograph is not a photograph in Barthes’ sense of the word. This is true of all digital photos, and not just the real images of fake people on “This Person Does Not Exist,” because the necessary connection to the real thing photographed has been severed and replaced by its connection with a string of 0s and 1s stored in a computer file. With the onset of the digital age, in the words of William Mitchell, there is now “an ineradicable fragility of our ontological distinctions between the imaginary and the real.”

*************

Jean Baudrillard, Enjoying a Gitanes While Thinking Deeply

So, if digital images are not photographs in the traditional sense, what is their ontological status – what kind of thing are they? According to Jean Baudrillard (1929 – 2007), French philosopher, cultural theorist, political commentator… and photographer, digital images are “simulacra.” Baudrillard was a Semiotics guy like Barthes, who wrote about diverse subjects, including consumerism, gender relations, economics, social history, art, Western foreign policy, and popular culture. He is best known, however, for his thinking about signs and signifiers and their impact on social life, in so doing popularizing the concepts of simulation and hyperreality. And, luckily for us, he was minimally aware enough of his surroundings not to get run over by a truck, like Barthes, and so lived to see the digital age.

Baudrillard’s post-digital world is made up of surfaces populated with self-proliferating “simulacra”, which are not copies of the real but their own thing, the hyperreal. Where classic philosophy saw two types of representation— 1) faithful and 2) intentionally distorted (simulacrum)—Baudrillard sees four: (1) basic reflection of reality; (2) perversion of reality; (3) pretense of reality (where there is no model); and (4) simulacrum, which “bears no relation to any reality whatsoever.” Digital photos are in the 4th category – simulacra – and are generated “by models of a real without origin or reality: a hyperreal. The territory no longer precedes the map… it is the map that precedes the territory. It is … whose vestiges persist here and there in the deserts that are… ours. The desert of the real itself.”

The problem with our new digital world, as Baudrillard sees it, is that our sense of reality is in the process of being inexorably altered by the endless profusion of non-reality based images, “simulacra.” In phenomenological terms, the categories we assign things to have been altered; that is to say, digitization has altered our ontology. As Sartre noted, from a phenomenological perspective, photographs form a distinctive category of objects. To see a picture as a photograph is to put it in a category. Now, for Baudrillard, to see something as a digital image is to locate it within the category of simulacra, the not-real, if only subconsciously (Baudrillard would say that we will gradually transition consciously once we’ve realized the ruse is up). This is the radical opposite of Sontag’s claim for analog photography. For Baudrillard, with digital’s severing of indexicality, we can never be certain what kind of image we are seeing, and so, by default, we must assign it to the category of simulacrum. Where once the image world provided us with windows onto reality, the image world now surrounds us in fictitious landscapes that heighten ontological uncertainty by eradicating the distinction between real and not real.

*************

A Photograph Taken with a Film Camera. These People Exist

What Barthes’ Camera Lucida Means in the Digital Era

French Post-Modernist Intellectual Roland Barthes, Pondering the Studium/Punctum Distinction With the Aid of Non-filtered Gauloises

Consider this Part Two of my previous post on Barthes’ Camera Lucida. There, I gave what I considered the gist of Barthes’ thesis on Camera Lucida, the main point you as a photographer can take away from the book. My intent was to de-mythologize the book and make it intelligible to an educated lay readership. In my opinion, any thinker who can’t articulate his thought so that it’s understandable to an educated lay reader probably doesn’t have very coherent ideas to begin with.

Which is not to say Barthes didn’t have much to say. He did. He just suffers from the annoying tendency of “French Intellectuals” to make their thought sound more profound than it really is by expressing it in jargon that obscures it. This has had the unfortunate result that it’s also allowed less interesting thinkers than Barthes, or often thinkers with nothing to say, to join the debate simply via having mastered the appropriate in-group jargon (read this woman if you have questions). Much of modern Semiotics thought, of which Barthes is a pioneer, is, honestly, a mess of incoherent garbled nonsense.***

While I’m not denigrating Barthes’ thought, it’s instructive to compare Barthes’ Camera Lucida with Susan Sontag’s On Photography, written about the same time. Where Barthes is maddeningly opaque – he speaks of “the wound” of the punctum, the “Dearth-of-Image,” the “Totality of Image,” i.e. the usual jargonist clap-trap – Sontag, good practical, American intellectual she is, gets to her point clearly and concisely, absent in-group jargon, seemingly without the need legitimize her thought by unnecessarily obfuscating it.

*************

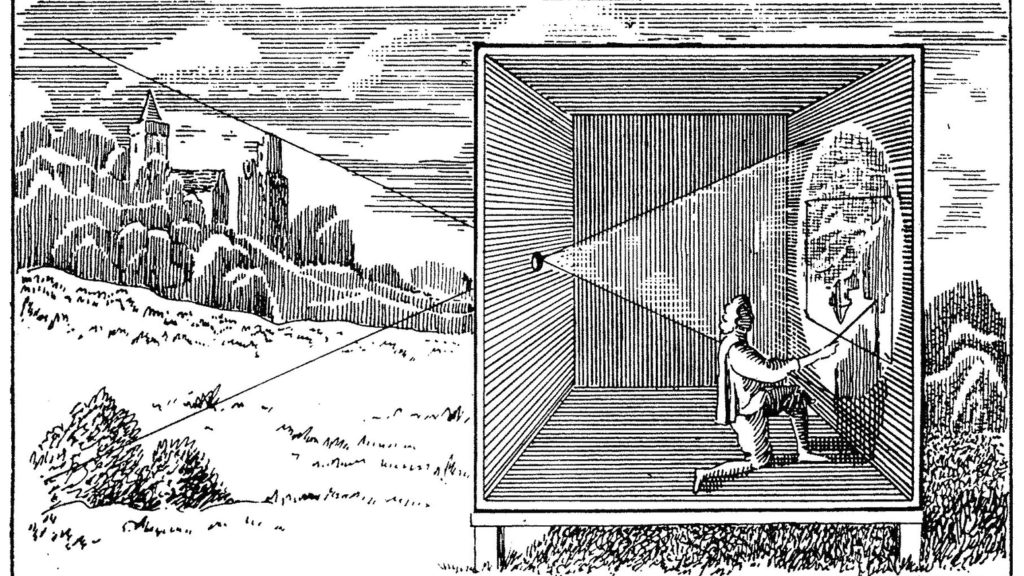

The Camera Obscura, Predecessor of the Photographic Camera

The question I posed at the end of Part One was this: What, if any, are the implications of Barthes’ ideas, as expressed in Camera Lucida, for ‘post-analog’ (i.e digital) photography? After posing the question, I then suggested the answer should be fairly obvious. As I see it, it’s this: Digital capture has severed the direct connection between the thing photographed and the resulting photo. “Photography” as commonly practiced today no longer possesses the one characteristic that made it unique among communicative media – its “Indexical,” as opposed to its “Iconic” relationship with what is real, what’s actually out there.** As such, you could argue it isn’t even “photography” anymore as the term is understood etymologically, but rather a new species of graphic arts. [Years ago, when I was naive enough to think that one could actually intelligently discuss issues like this on the net, I suggested this on a popular photography forum, whereupon forum “mentors” chortled at such  ridiculousness (one “mentor” – a retired insurance salesman who mentors readers on the intricacies of varoius camera bags – opined that only an idiot could think such ludicrous things), forum members pointed at me and laughed, moderators’ heads exploded, and shortly after I was summarily banned, for life, no possibility of reprieve, banished to the nether regions of web-based photographic discourse. My response? I started Leicaphilia.]

ridiculousness (one “mentor” – a retired insurance salesman who mentors readers on the intricacies of varoius camera bags – opined that only an idiot could think such ludicrous things), forum members pointed at me and laughed, moderators’ heads exploded, and shortly after I was summarily banned, for life, no possibility of reprieve, banished to the nether regions of web-based photographic discourse. My response? I started Leicaphilia.]

At the time Barthes wrote, when photography was the result of analog processes identical to those of the camera obscura (see above), we could rightfully assume that a photo necessarily dealt in the real and was more or less faithful evidence of the real. While someone could manipulate an analog photograph to a certain extent, the exception proved the basic rule: photography, in the words of Susan Sontag, was the stenciling off of the real. It was “evidence” of the real. For Barthes, that’s what makes photography absolutely unique as a medium of communication, Its very essence as a medium.

Digital capture doesn’t “stencil off” anything; rather, it turns everything into computer code which then needs to be reconstituted by more computer code. The “digital revolution” isn’t about simply providing more efficient photographic tools; rather, it’s a profound revolution of how we recreate the visual with similarly profound implications for its claim to being “true” by simply being. Unlike the photographic processes Barthes analyzed, digital processes de-materialize everything into non-material 1’s and 0’s ephemerally housed in computer “memory,” data that must then wait for an algorithm to reconstitute it “realistically” or transmogrify it into anything else imaginable, dependent upon the intentions of the algorithm’s creator. Need to make your selfie more sexually attractive, your landscape more picturesque? Need to remove an ex from a family portrait? There’s a “filter” (i.e. a certain computer algorithm designed to translate the latent data a certain way to acheive a certain pre-determined result) for that. Hell, those 1’s and 0’s that constitute the RAW file, or the DNG or the JPG, can just as easily be output as music if that’s your desire, the point being that the guarantee of indexicality that Barthes sees as exclusive to photography is a thing of the past. To quote Wim Wenders: “The digitized picture has broken the relationship between picture and reality once and for all. We are entering an era when no one will be able to say whether a picture is true or false. They are all becoming beautiful and extraordinary, and with each passing day, they belong increasingly to the world of advertising. Their beauty, like their truth, is slipping away from us. Soon they will really end up making us blind.”

The blind already exist. They’re the smug enthusiasts who think an interest in “photography” only means better cameras with greater resolution, easier capture and hassle-free output, who would dismiss those like Wenders who recognize something more profound at play while they simultaneously embrace – no, celebrate – the technologies undermining and ultimately destroying photography itself.

**Indexical Signs = signs where the signifier is caused by the signified, e.g., light enters a camera lens, is focused on a silver halide substance, and produces a negative via a photochemical process. Iconic signs = signs where the signifier resembles but is not directly caused by the signified, e.g., a digital “photo”, wherein the “photo” has no direct causation by the signified and thus can only be said to “resemble” the signified.

*** For an example of what passes for intelligent discourse in Semiotics, this from the Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, literally opened at random :

The phenotext is constantly split up and divided, and is irreducible to the semiotic process that works through the genotext. The phenotext is a structure (which can be generated, in generative grammar’s sense); it obeys rules of communication and presupposes a subject of enunciation and an addressee. The genotext, on the other hand, is a process; it moves through zones that have relative and transistory borders and constitutes a path that is not restricted to the two poles of univocal information between two full-fledged subjects.

To create your very own post-modernist essay, go here and click on the generator at the top of the page.

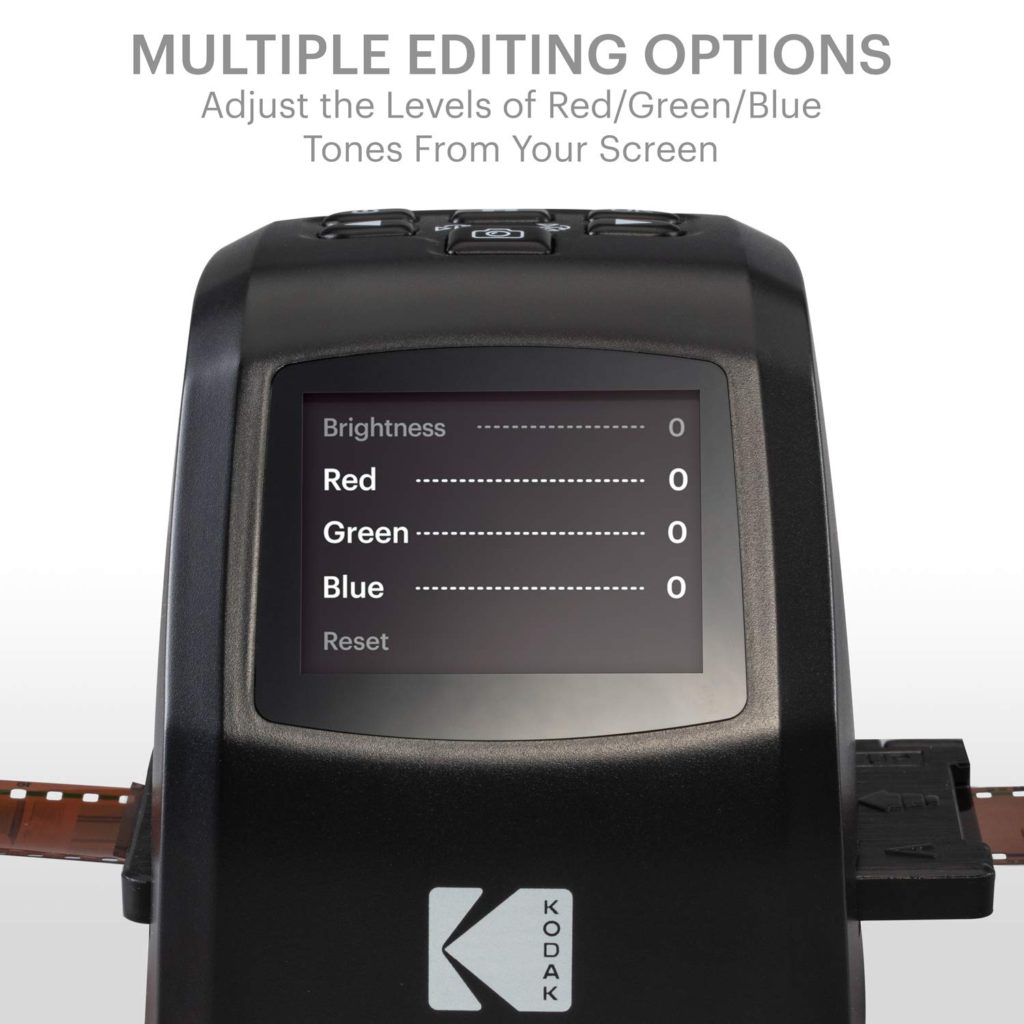

Is This the Scanner Film Users Have Been Asking For?

Made by Kodak, no less. Price $130. The ‘Kodak Mini Digital Film & Slide Scanner’ is a complete stand-alone unit (i.e. you don’t connect it to your computer) that converts 35mm film negatives into 14 or 22 mpx JPEG files. It’s small, has an integrated 2.4” LCD screen, one-press button operation, “simple user interface” and easy-load adapters for 135, 126, 110, Super 8 and Monochrome negatives and slides. It saves up to 128MB.

- Maximum Compatibility & Ease of Conversion w/ a Variety of Adapters Designed for Fast, Continuous Loading; Quality Up to 14/22MP w/ Adjustable Brightness, Color & Reverse/Flip

- UP2.4 LCD “User Interface” with Dedicated Scan & Home Buttons Provide One-Press Scanning & Quicker Menu Navigation; View & Edit Current Slide or Gallery Pictures on the Color Display [Internal Memory Holds Up to 128MB]

- Plug to View: The back of the device features an SD card slot, mini USB power connection and TV-out connection with cables included.

- Continuous Loading: Film and slides move effortlessly through the gadget’s loading dock, providing faster, smoother performance.

- Buttons include power, left arrow/reverse function, home, ‘Ok,’ right arrow/flip function and scan/capture for one-press convenience.

- Use Any SD Card Up to 32GB or Hook Up to Computer, Laptop or External Device Via USB 2.0

- Extended Accessories Pack Includes Universal Power Source for US, EU & UK, Cleaning Wand, USB Cable & TV Cable Power Adapter; Send & View Images on Mac/PC Computers, Big Screen TV, Etc.

No need for dedicated software programs, specialty machinery or even a computer to run it. Once your chosen adapter is installed, “smart technology” converts each slide or negative into a JPEG file that you can save via internal or external memory. Keep loading for “fast, continuous” photo scanning (I’ll believe that when I see it).

You view and edit photos on the scanner, so there’s no need for secondary software. Once the image appears onscreen, you use the flip and reverse functions to change orientation, adjust brightness and RGB values. Depending on the film scanned, the scanner allows you to “enhance resolution from 14 to 22 megapixels,” whatever that means.

Full Specs:

- Image Sensor – 14.0 megapixels (4416×3312); ½.33” CMOS sensor

- Display – 2.4” color TFT LCD

- Exposure Control – Automatic/Manual (-2.0 ~ +2.0 EV)

- Resolution – 14 megapixels/22 megapixels

- Scannable film types – 135 film (36 x 24mm), 126 film (27x27mm), 110 film (17 x 13mm), Super 8 film (4.01 x 5.79mm), Monochrome film, slides

- Scannable picture formats – B&W, slides, negatives

- Scanned file format – JPEG

- TV-Out Type – NTSC/PAL

- External Memory Support – SD Card

The only real downsides I see are these: First there’s no bulk scanning option like the Pakon, where you can scan an entire roll at one go; scanning is limited to single frames, with the caveat that it claims “fast, continuous” scanning if you’re willing to sit and feed it. Second, it’s limited to JPG output, so it may not be the best solution for those who intend to significant post-processing. For sharing output on the web, or simply for digital archiving, it looks really interesting.

Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida, Part One

The Studium of This Photo: Roland Barthes in 1980. The Punctum (For Me) of This Photo: Shortly After, Barthes Got Run Over by a Laundry Truck

” Color is a coating applied later on to the original truth of the black and white photograph. ” That’s a great quote, maybe my favorite thing Barthes has written. Funny I don’t remember having seen it before, but there it is on page 81 of Richard Howard’s translation of Camera Lucida published by Hill and Wang. I ran across it while re-reading the book. The quote stuck out for me because it’s so quotable, the sort of pithy bon mot that fits great in an essay about  photography. And it’s by Barthes no less, so it’s got tons of “crit lit” street cred. You’d think others would have liked it and used it, and I’d have run across it numerous times in past readings, given I read a lot about photography. But no, I’ve never seen it before.

photography. And it’s by Barthes no less, so it’s got tons of “crit lit” street cred. You’d think others would have liked it and used it, and I’d have run across it numerous times in past readings, given I read a lot about photography. But no, I’ve never seen it before.

Which is further proof of what I’ve long suspected: All sorts of people – from academic ‘critical theorists’ to the pretentious no-hopers who congregate on photography websites – love to reference Barthes’ “seminal” work about photography, Camera Lucida, but few of them have actually read it. It’s the sort of book one must be conversant with when one is “serious” about photography, but in reality, nobody reads it. They just discuss it as if they had, with other serious people who haven’t read it either, repeating its fashionable jargon deliberately conceived to exclude those not in on their “discourse.”

*************

Some general background about Barthes: Barthes was/is a French literary theorist, philosopher, linguist, critic, and semiotician, a “post-modern” deconstructionist whose work has influenced structuralism, semiotics, social theory, design theory, anthropology, and post-structuralism. Suffice it to say that he was/is the poster boy for the French Post-Modernist Intellectual, a quasi-Marxist true believer in a Nietzschean relativism that holds there is no truth, no argument superior to any other argument (which, if you think about it, is completely contradictory on its face). I’ve written about him before here, which should tell you more than enough of what you need to know about Barthes.

So, assuming you haven’t read it, let me give you the Cliff Notes on Barthes’ Camera Lucida. It’s simple, and it’s this. What makes photography unique is the fact that it faithfully records the fact that something has been. Something was there, actually existed, reflected actual light rays, those light rays imprinted themselves on a film media, and the end result is an artifact – the photo – that possesses, in some significant sense, the essence, the being of that thing photographed. And this is the essence of photography as a representational medium.

*************

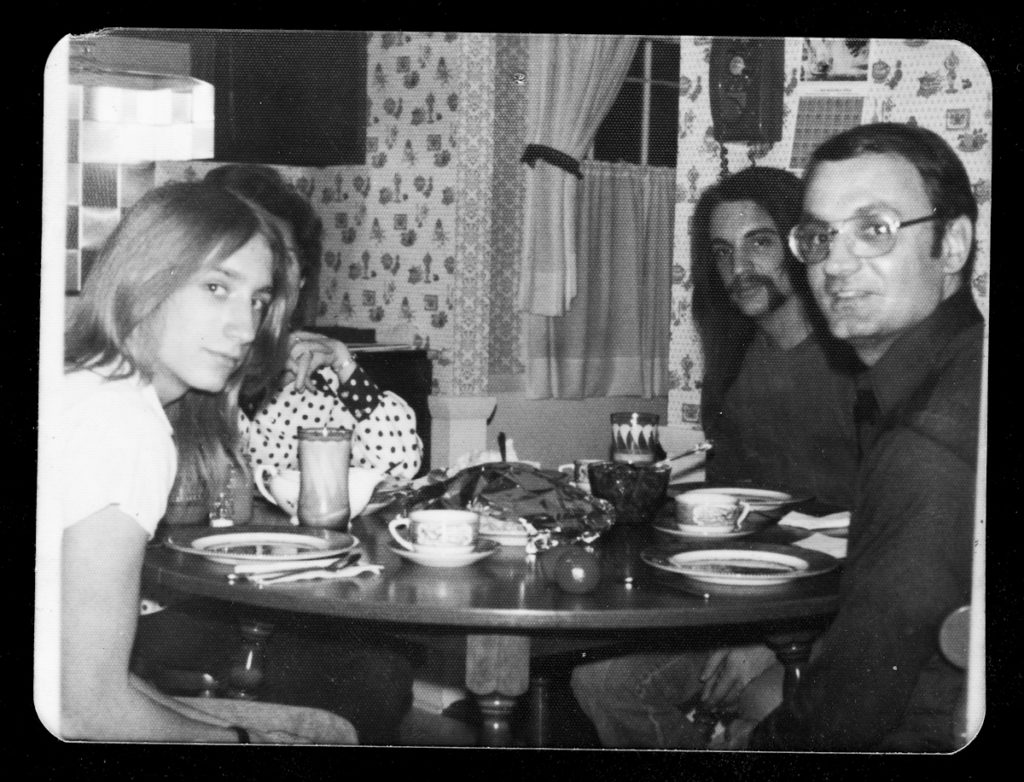

Wayne New Jersey, 1974. The Studium: Me, My Brother and My Dad. The Punctum: My Brother Looks Like Harry Shearer in Spinal Tap.

Barthes then goes on to analyze what makes some photography more arresting than others. This is where Barthes introduces the idea of the studium and punctum and the distinction between the two. Every photo has a studium. The studium is simply the subject of the photo – the thing, the person, the landscape etc. – the thing that was there in front of the camera, the thing the photograph describes. One thing we know about this studium is that it existed at the time the photograph was taken. We know this because photography has this indexical relationship with the real. By its very nature, photography deals with real things.

What differentiates photos from each other for the viewer is the presence or absence of the punctum, which is the emotional significance of the photograph for the viewer. The punctum is the viewer’s subjective response – something not there but merely hinted at- that jumps out of the picture at you, that says something to you over and above what simple definitional reading of the picture would imply (“that’s a picture of my mother”), that takes you out of the four corners of the photograph and transports you to a world outside of the photograph. That’s the punctum.

To illustrate the distinction, Barthes discusses a photo of his mother, the “Winter Garden” photo, a photo he has of her as a child, standing with her brother at five years of age, assuming a certain self-conscious pose, her fingers of one hand held awkwardly in the other. The punctum of the Winter Garden photo for Barthes is this: this photo leads him back to the realization that his Mother, now dead, existed, and she existed before Roland existed, and this photography contains some part of her. She stood in front of a camera, with her brother, wearing those clothes, and held her hand like that, light reflected off of her and stenciled itself onto the physical medium of the film. The photo is physical evidence of her presence, evidence stenciled directly off the real. To put it another way, the punctum of the Winter Garden photo for Barthes is his realization of the existential reality of this particular studium. Deep.

*************

The Studium: Semana Santa Easter Celebration in Valencia. The Punctum? Up to you.

The studium/punctum distinction is interesting, but it’s only marginally related to the book’s main point. You wouldn’t know it, however, by reading about the book in the usual echo-chamber. The studium/punctum distinction is secondary to a much larger and more important point Barthes is making: that what constitutes photography is its indexical relationship with what is real, what’s actually out there, and this relationship is unique among every other communicative media. Photographs, unique among other means of representation i.e. painting, writing or speaking, necessarily deal in the real and are evidence of the real. That’s the magic of it. While someone can manipulate an analog photograph to a certain extent, the exception proves the basic rule: photography, in the words of Susan Sontag, is the stenciling off of the real. Nothing else is, and that’s the value of photography and why it holds a special status as a communicative medium.

Think of it this way: A painter can paint something and present it to the viewer. What he’s painted may represent something that exists/existed, or it may represent something that does not exist, never has existed, a figment of his imagination or something he hasn’t seen. While he can claim it’s an accurate representation of the real, we can never know for sure. Likewise, a writer, using language as his device of representation, can write something purporting to be the truth about something real – or he could be writing something fantastical, void of reality, something that’s never been. It’s up to him to tell us, but again, we can never be certain. We have to take his word for it, and as such, it has a compromised ability to constitute what we refer to as “evidence.”

A photograph, however, by its very nature, requires something to have been there, something existing as a physical thing in time and space, something that existed. This is the essence of photography for Barthes, and it’s basically the point of the book. Photography gives us a direct representation of the real.

Cogitate on that for a while, and think about what implications it might have for ‘post-analog’ photography…

Coming Soon, Part Two: What Barthes means in the Digital Era (hint: Not many people talk about it, although it should be fairly obvious)

Perfection and Its Discontents

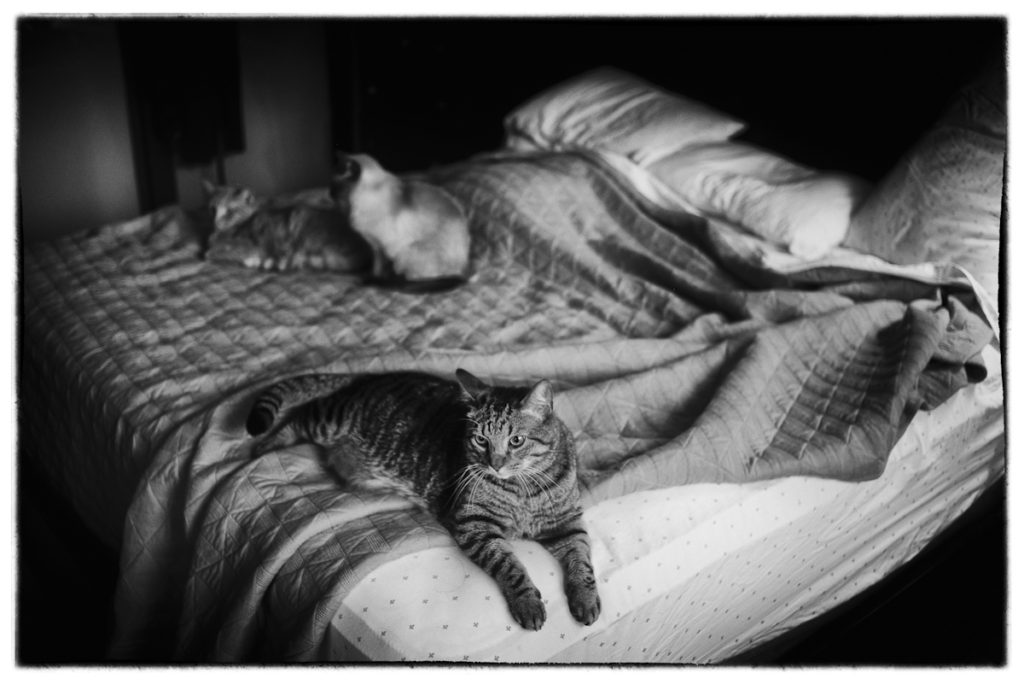

Every Leicaphile Loves a Good Cat Picture. This was Shot Digitally, But Looks to Me A Lot Like a Well-Printed Film Negative, Plus-X Maybe?

I make no secret of the fact that I love the look of 35mm B&W film. A properly exposed, competently printed 35mm Plus-X, Tri-X or HP5 negative has a beauty that simply cannot be matched by a digital file of whatever native quality. In comparison to the film print, the digital print will always have a certain thinness, a lack of heft, a “plastic” look. While it’s hard to put into words – given we’re talking of visual matters – it’s there, I can see it, it’s real (I think).

There’s an organic quality to a film print, as best I can tell the product of four inherent characteristics of shooting film: 1) silver grain as the light-transforming medium; 2) better highlight rendering, the result of the fact that film, unlike digital capture, does not record exposure values linearly, as does digital capture, but compresses those values at both ends of the exposure curve, giving better highlight definition (e.g. it is less prone to “clipping” highlights) and deeper, “richer” shadows (old-school film photographers know exactly what I’m saying here, digital era photographers will mostly be clueless – for further discussion, see this); 3) the inherent resolution limitations of general purpose b&w films like HP5 or Tri-X, which, to my eye, equal in look somewhere between 6 and 8 mpx of digital resolution, in combination with the less resolute optical characteristics of film era lenses, which were developed to give an appealing look within the confines of limited film resolution; and 4) the necessity of shooting at the low ISO’s required by film. Put all of four of these characteristics together holistically, and you have the “film look,” a result of both the native strengths, and inherent limitations, of silver halide as a medium.

Unfortunately, that “film look” is difficult to present online in the sense that a scanned film negative – a requirement to presenting it for web viewing – looks different from a wet printed film negative, the difference created by the digitization itself. Scanned film negatives usually have more pronounced, harsher grain that is not present in a wet printed version of the same negative, the result of the relative harshness of the scanner’s light source, which artificially accentuates grain when compared to the same sized wet print, where the enlarger’s light source is more diffuse and produces smoother grain texture. Anyone whose both wet printed and scanned and then inkjet printed the same negative knows precisely what I’m talking about, but it can’t be represented digitally because scanning is a necessary prerequisite to do so.

*************

The CMOS Version Leica MM

Given my preference for B&W, which to me is “real” photography, I admire the Leica Monochrom cameras, and I admire Leica sticking their necks out to produce them, an example of Leica at its best, attempting to carry on their patrimony into the digital age. However, unlike how they marketed the MM – bundled with Silver Efex and referring back to 50-60’s era B&W photography – the MM isn’t going to digitally replicate B&W film; at best, it’s going to create a new look – “digital B&W”. [ Ralph Gibson seems to understand this]. Given what was said above, it becomes obvious why a dedicated B&W digital camera can’t digitally duplicate traditional B&W photography. Stripping the color out of the capture won’t address the inherent exposure curve differences between analogue and digital capture, and the increased resolution of the Monchrom vis a vis standard 35mm B&W film compromises the look as well. Given the native differences in capture, no amount of running the Monochrom digital file through film emulation software will accurately mimic real B&W film.

Where the MM might have an advantage in replicating the film look might be to the extent it allows use of older film era rangefinder lenses. Mandler era Leitz optics give a certain signature we equate with film capture, both in the look of how they resolve details and also in the look given by lenses with the small film to flange distances typical of rangefinder as opposed to Reflex systems. Of course, this would only be true to the extent when we’re speaking of a traditional “film look” what we really mean is the look give by 35mm film rangefinder photography. If so, then the MM can’t in any way be inherently better than any other full color capture digital Leica rangefinder (e.g. M8,M9,M10) given the defining shared characteristic is a function of film to flange distance unique to any digital rangefinder or, for that matter a mirrorless design, that allows the use of traditional rangefinder optics created to take advantage of small film to flange distances. My experience with the lower resolution M8 confirms this: I’ve always thought a greyscaled M8 file with some grain added looked more like native B&W film than did the files from the MM, probably a result of the M8’s decreased resolution coupled with its ability to use film era Leitz lenses.

*************

The Fuji S5 Pro. Its Files Look A Lot Like Film. There’s a Reason…

Which gets me to the premise of the title of the post: much of what we identify as the strength of film – the film look – is a consequence of its limitations, its imperfections, imperfections that are a part of its character. As digital technologies have advanced and matured, the photos they produce, while closer approaching a technical “perfection,” have lost character. As a consequence, those of us educated by experience to notice it often end up dumbing digital RAW files down to mimic the imperfect look of film.

For my money, the Fuji S5 Pro digital camera, produced by Fuji in 2007 using the Nikon D200 chassis and Fuji produced Super CCD SR (Super Dynamic Range) sensor, comes as close to replicating the traditional B&W film look as any digital camera I’ve used. It may be just me, I don’t know, but the S5 files, run thru Silver Efex, even without using any specific film emulation (e.g. no specific film exposure curve applied, just grain added), have a certain solidity to them, a lack of that “plastic” brittleness often characteristic of digital black and white. After thinking about it, I’ve concluded that the S5 mimics the traditional B&W film look because of both its unique extended latitude sensor but also because of its inherent technical limitations.

The SR Sensor found in the Fuji S5 Pro – either 6 or 12 mpix depending on how you define it – offered almost two stops more dynamic range than conventional CCDs of the same era (2007, roughly the M8 or D200 era). Beneath each micro-lens on the sensor surface are two photo-diodes, the primary capturing a dark and normal light levels (more sensitive), the secondary capturing brighter details (less sensitive). The signals from the two photo-diodes are then combined by Fuji’s in-camera software to deliver an image with extended dynamic range. What’s of interest for film users is the way the extended dynamic range is achieved. Unlike normal cutting edge CMOS sensors that give excellent dynamic range, the Fuji gives a certain type of dynamic range, a type that more closely mimics the type of dynamic range given by film, the added latitude at the highlights. Like film, you’ve really got to work to clip the highlights on an S5 DNG file.

Fuji S5 RAW Run Through Silver Efex to add Grain. No Specific “Emulation” used i.e. Tonal Range is as S5 Sensor Captured It

A lot of this is subjective, no doubt. There may be something similar to a “placebo” effect, where believing is seeing. I’m willing to entertain the possibility that I’m as clueless as this guy when discussing my preference for the Fuji S5.*** What I do know is this: I really like my S5 for B&W capture, especially when I print as the end product. It checks many of the film experience boxes – low ISO capability (500 ISO is about as high as you want to go), having to work within the constraints of limited resolution, ability to use film era lenses (in this case, old MF Nikkors for the 50’s-70’s), excellent highlight rendering. Much like a 35mm film camera, the S5 is a camera that’s as much about its limitations as its strengths, limitations the photographer must work around, or within, the resulting images in part a consequence of those limitations.

The irony is that most people chase the film look by looking to digital cameras with ever increasing resolution, dynamic range, ISO capabilities etc, when a more thoughtful, and effective approach, might be to embrace technically less capable digital tech like the Fuji S5.

[*** “Comparisons” like this guy’s tell you nothing, typically accompanied as they are by statements like “However, there is an impression of clear intent demonstrated by that lens” (huh?) . This is the sort of fuzzy thinking cloaked as rational analysis that drives me nuts. Which begs the question: Am I doing the same thing? I suspect that some folks will see this essay as basically the same thing – a word salad dressed up objective analysis. And then there’s the cat pictures….]