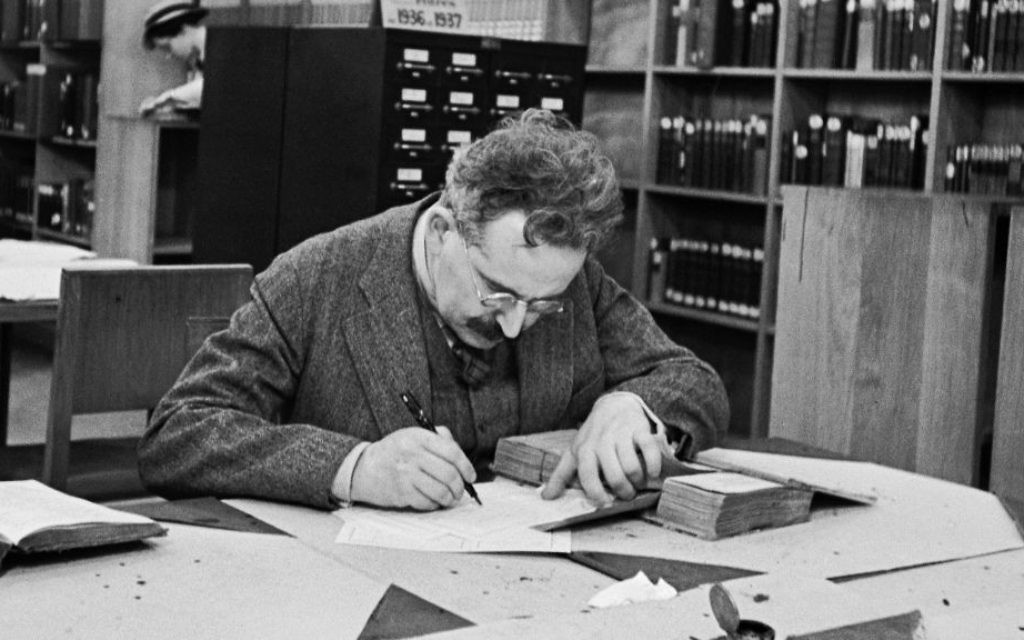

The German philosopher Walter Benjamin overturned the by now anachronistic conception of Charles Baudelaire, who divided art into two opposing camps : on the one hand the imaginative ( true artists who want to “illuminate things” with their subjectivity) and on the other hand realists (who want to “represent things as they are” but have no real means to do so). Benjamin’s essays – Little History of Photography in 1931 and, more importantly, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction in 1936 – argued that photography had finally emancipated art from the imaginative dimension that he claimed had heretofore characterized all traditional artistic work, and as such was a watershed historical moment in the history of imagery production.

Even in the era of prevailing subjective pictorialism forward looking photographers took up Benjamin’s call for realism, seeing in photography a unique medium to approach and recreate the truth for other’s purview. Among these, in America, were Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine who used photography as a tool for social investigation and denunciation. In France Eugene Atget documented a disappearing Paris.

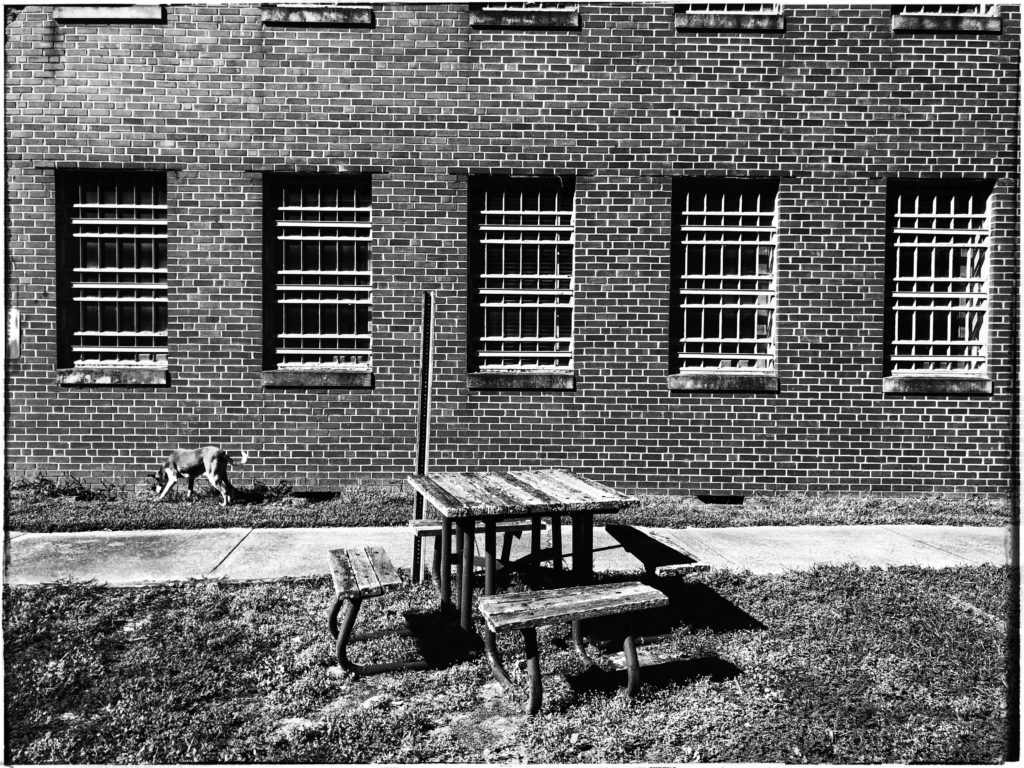

In America, Jacob Riis fathered modern social investigative photography. Emigrated from Denmark, he initially worked as a police reporter, but then devoted himself to photographing the most disadvantaged areas of New York. In 1890 he published his book How the Other Half Lives: Studies on New York Tenements ,where he documented the life of immigrants in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, then the most densely populated area of the world, with over half a million people in one square kilometer. Riis’s work spurred New York Governor Theodore Roosevelt to take government action to alleviate the retched social conditions Reis met there, and as such is remembered as one of the most influential photojournalists who documented the social injustices of America between the end of the 1800s and the beginning of the 1900s.

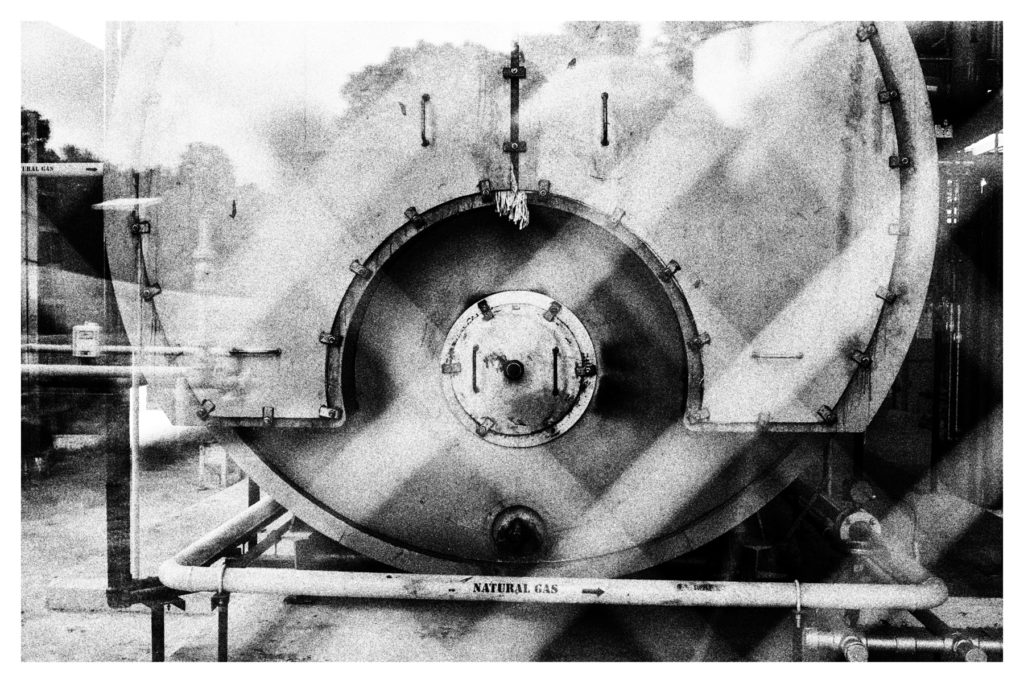

Lewis Hine, a teacher at the Ethical School in New York, used photography as a sociologist, photographing the life of immigrants on Ellis Island. In 1908 Hine became an official photographer of the National Child Labor Committee , an organization created to combat child labor in heavy industry. There he used photography as an instrument of social protest, accurately representing child laborers and their working conditions.

*************

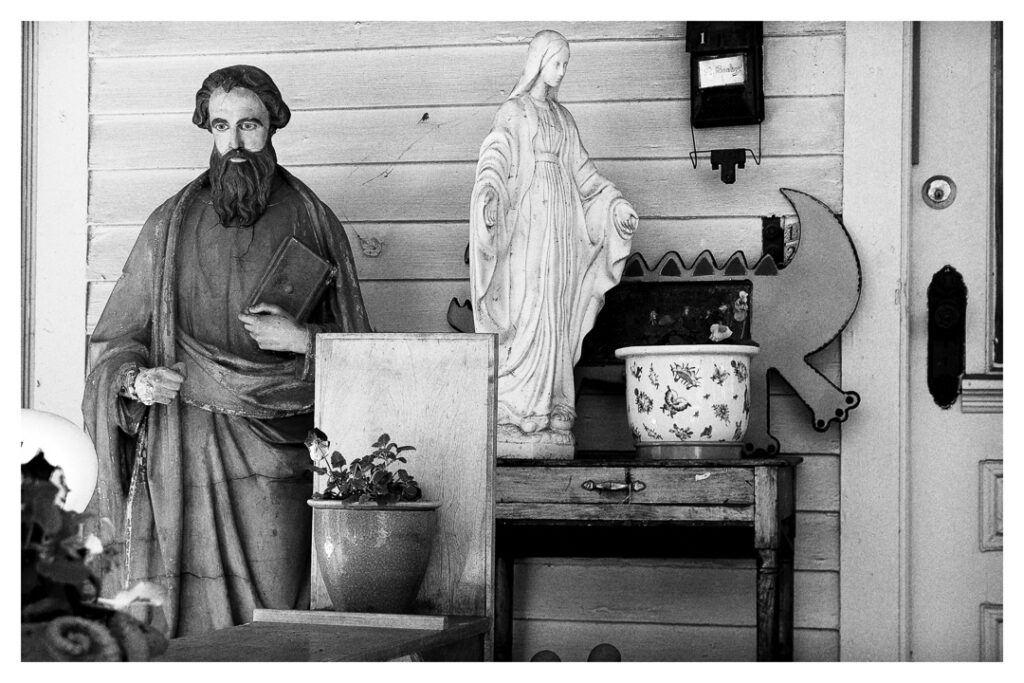

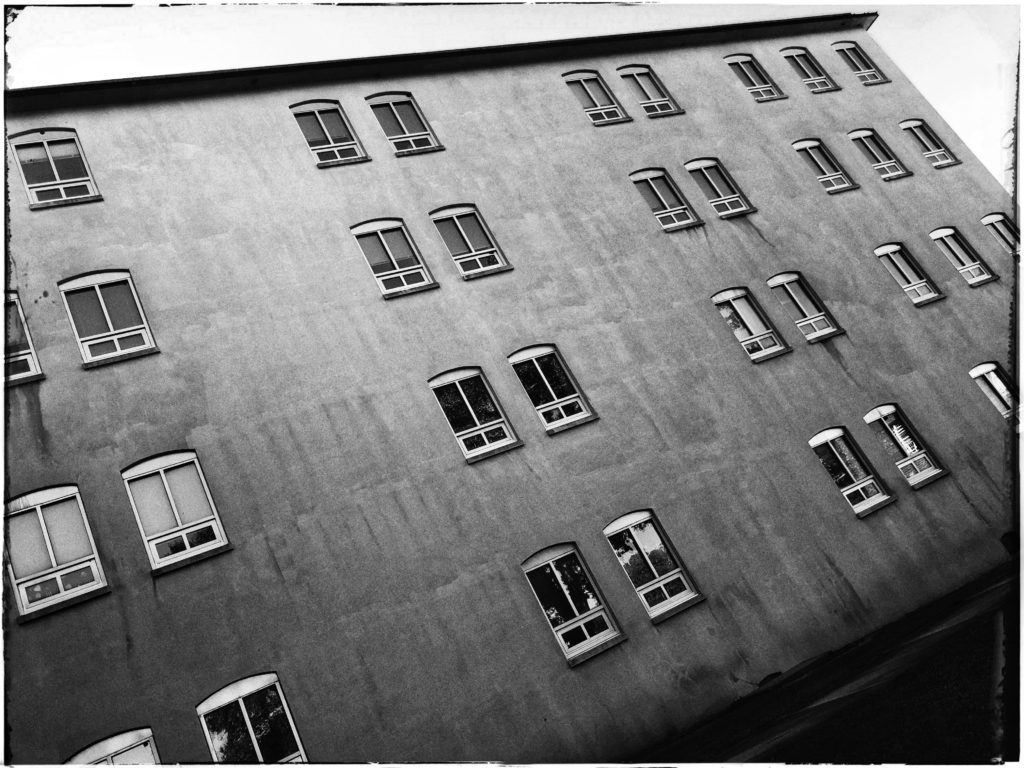

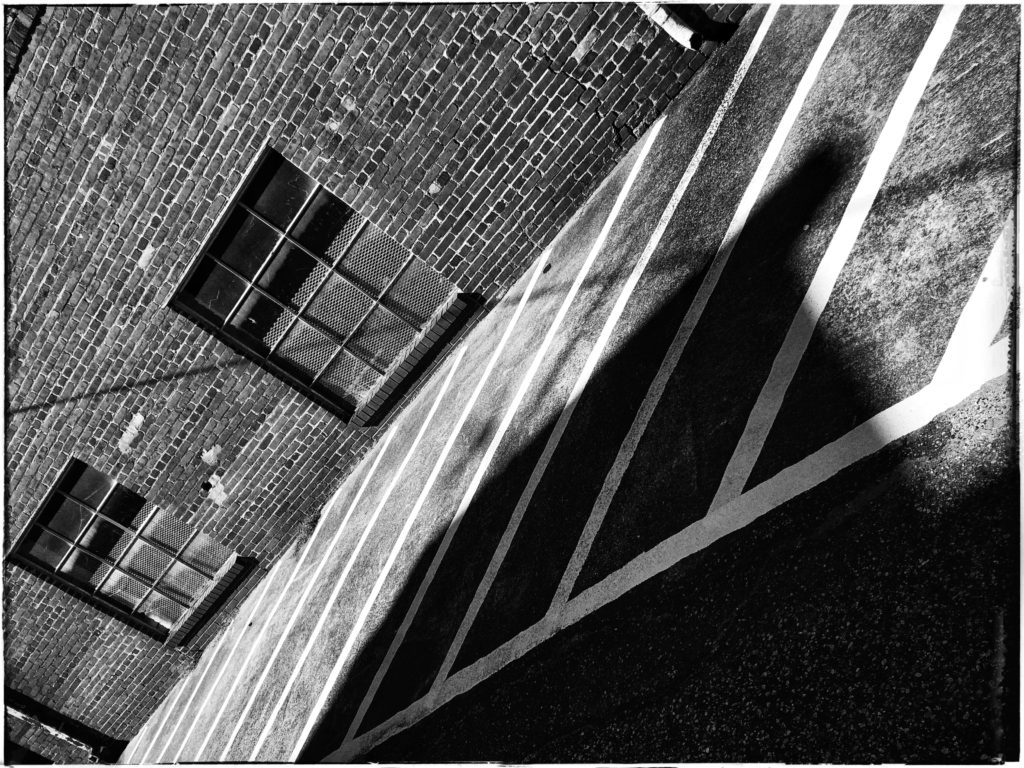

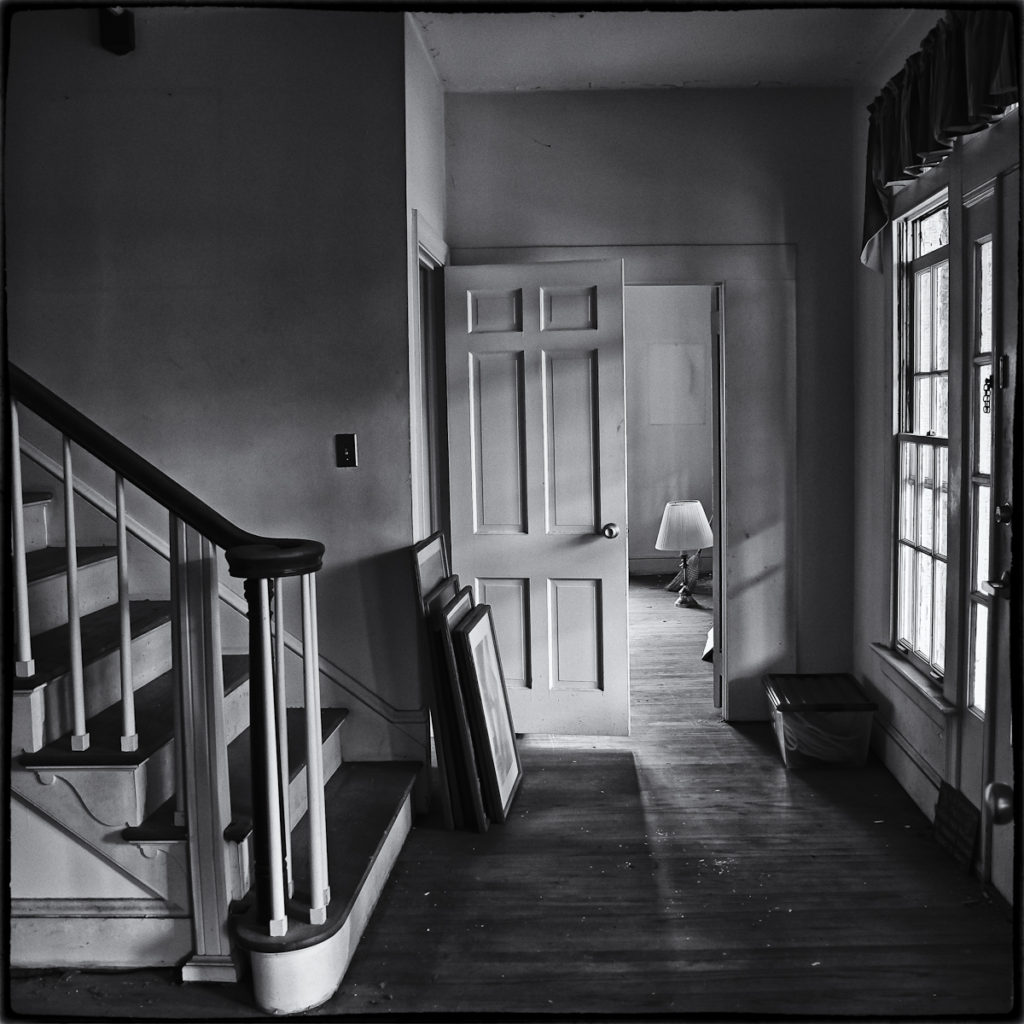

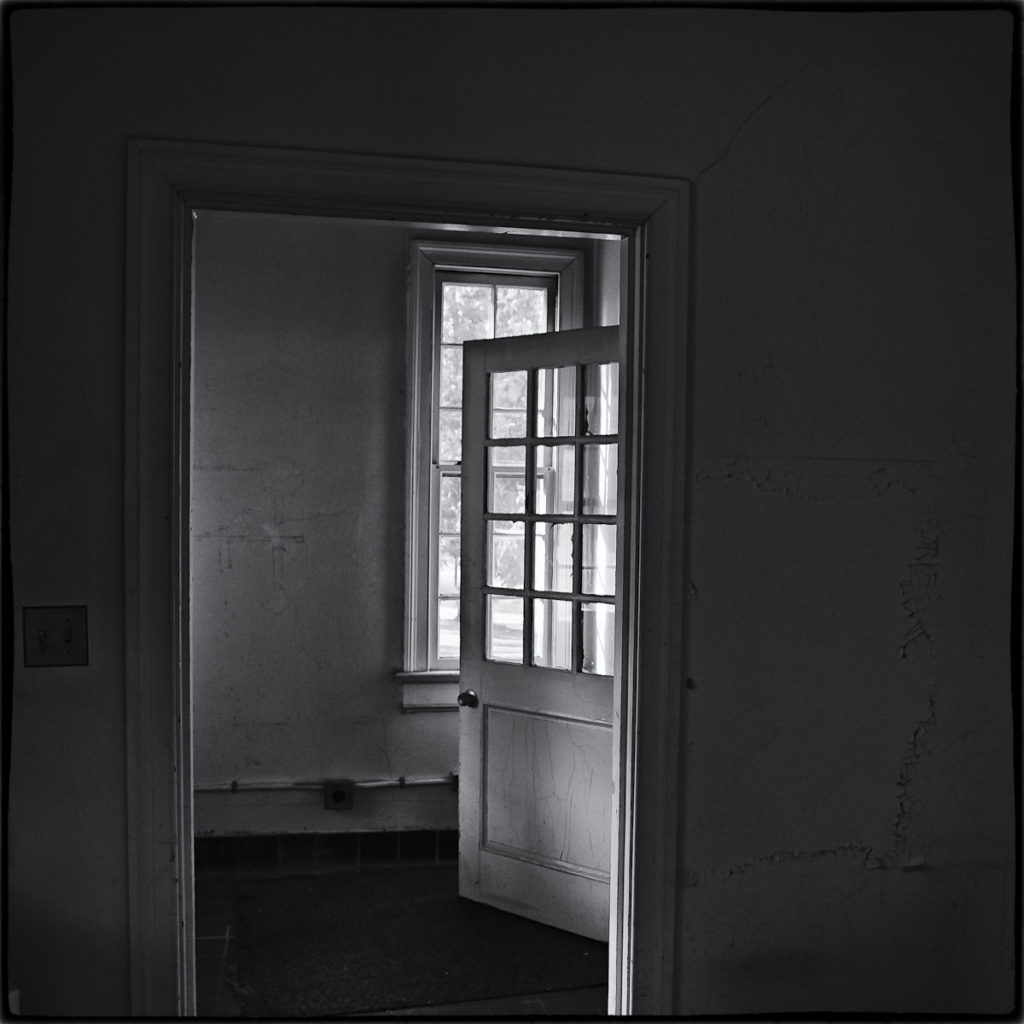

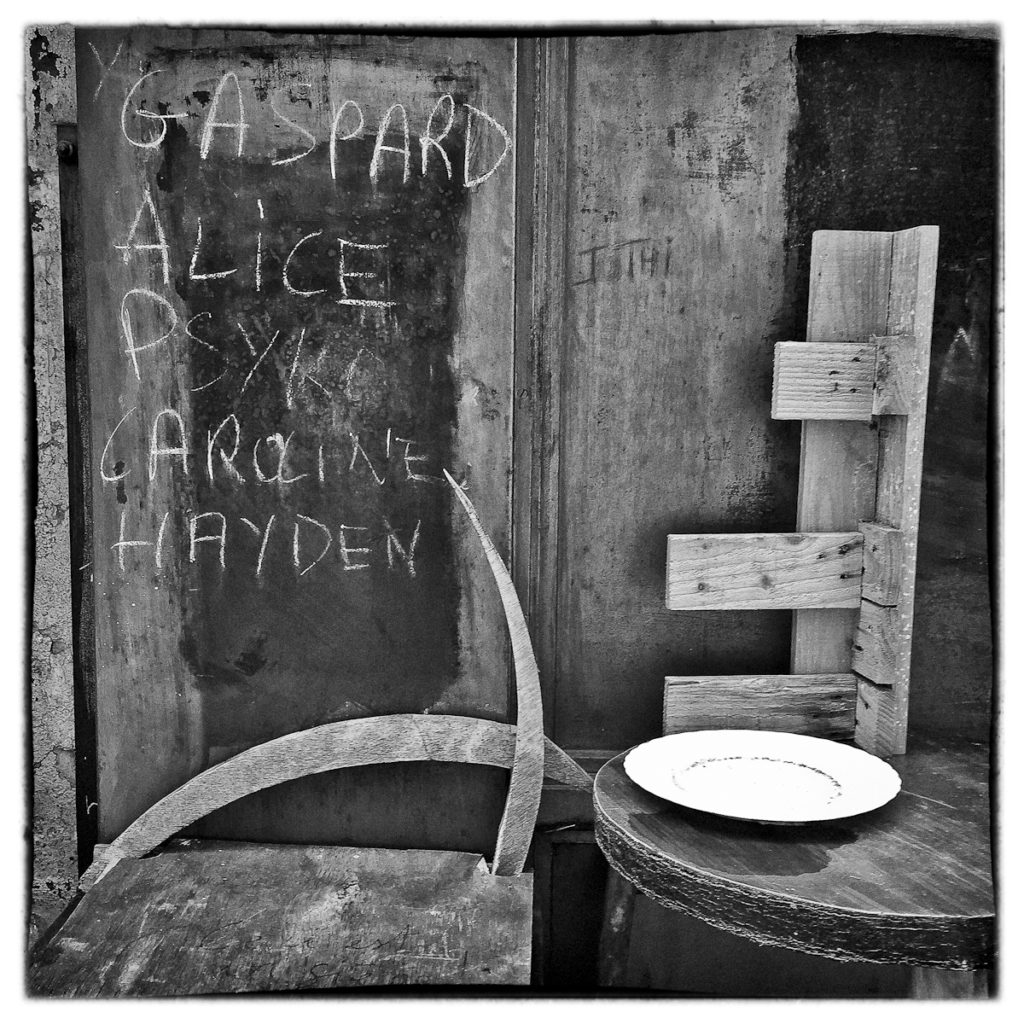

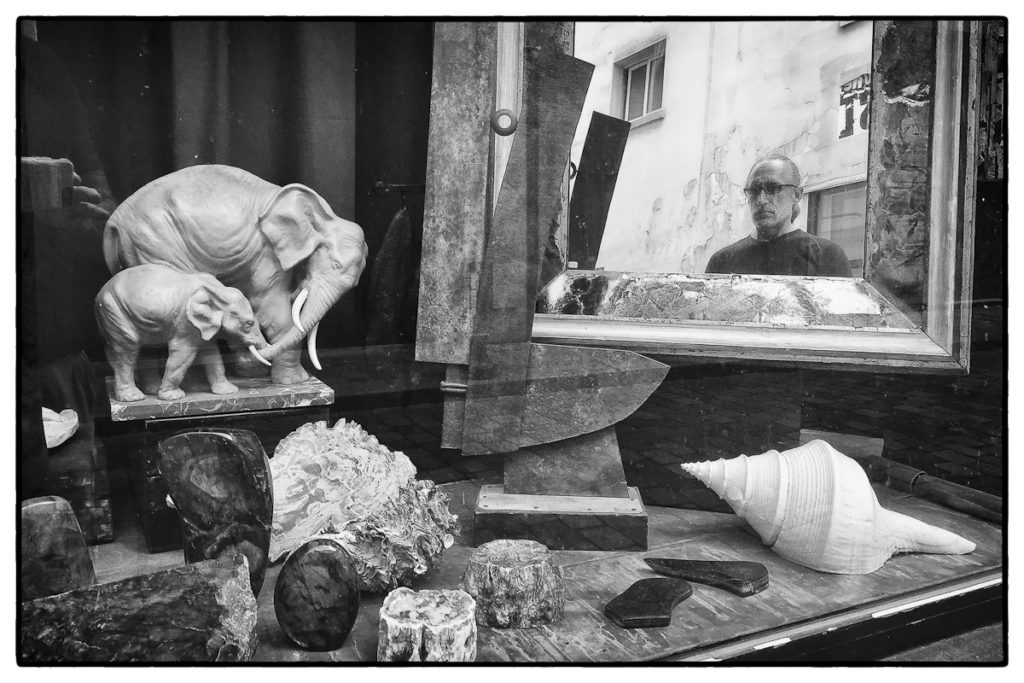

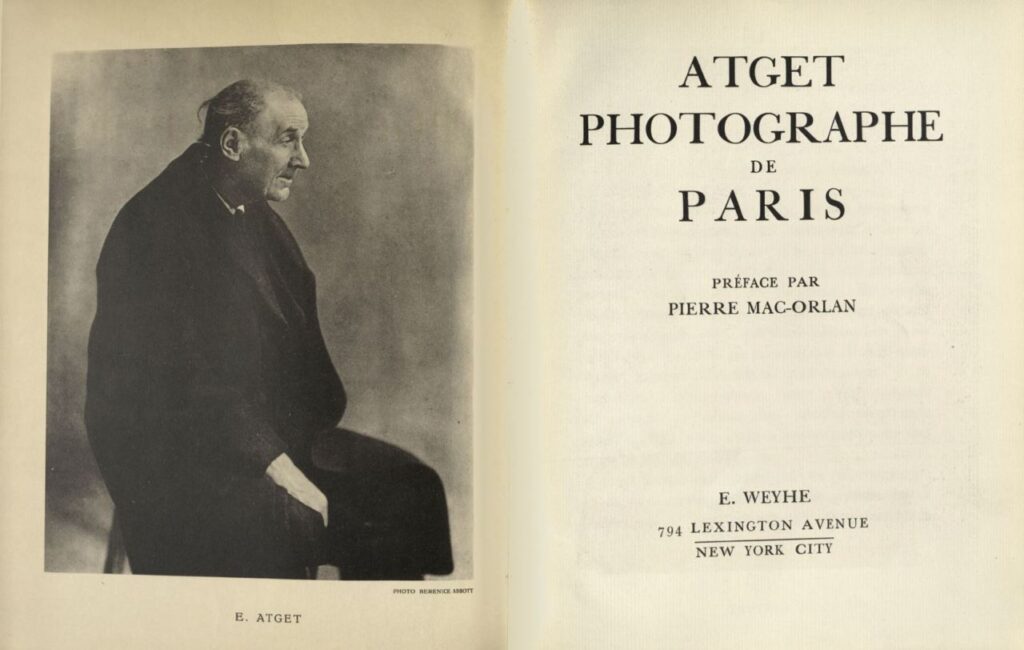

From 1889 to 1924 Eugene Atget documented old Paris, which was transforming itself into a modern metropolis, “manifesting from the outset the ambition to create a collection of all that is artistic in and around Paris”. He considered himself a commercial photographer, so much so that in 1890 he exhibited a small plaque outside his laboratory with the inscription “Documents for artists”. With his 18×24 bellows camera, a heavy wooden tripod he systematically photographed Paris, its architecture, shops and shop windows, along the way garnering the interest of the Surrealists like Man Ray and Brassaï, who saw in Atget a surrealist approach (i.e. highlighting and magnifying the real).

Atget died relatively unknown in 1927, although some of his prints were present in various archives in Paris. Atget’s artistic recognition was posthumous, thanks to the interest of Berenice Abbott ,who after Atget’s death bought the collection of Atget’s negatives and prints. These are now housed in the Museum of Modern Art in New York. In 1930, Abbott published the first book of Atget photographs, Atget, Photographe de Paris. From this moment his fame grew, so much so that he is consecrated as one of the most influential photographers of the early modern age: appreciated and recognized both by ‘realist’ American photographers such as Walker Evans, Ansel Margaret Bourke-White and by Europeans André Kertesz , Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Frank and Josef Koudelka.

*************

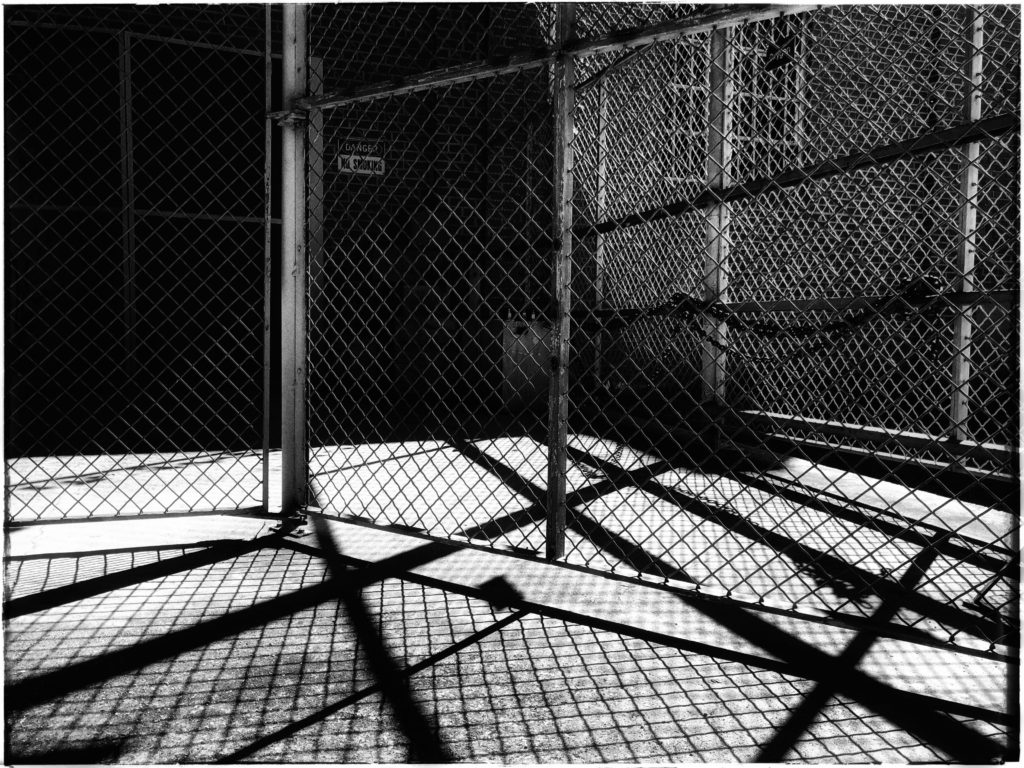

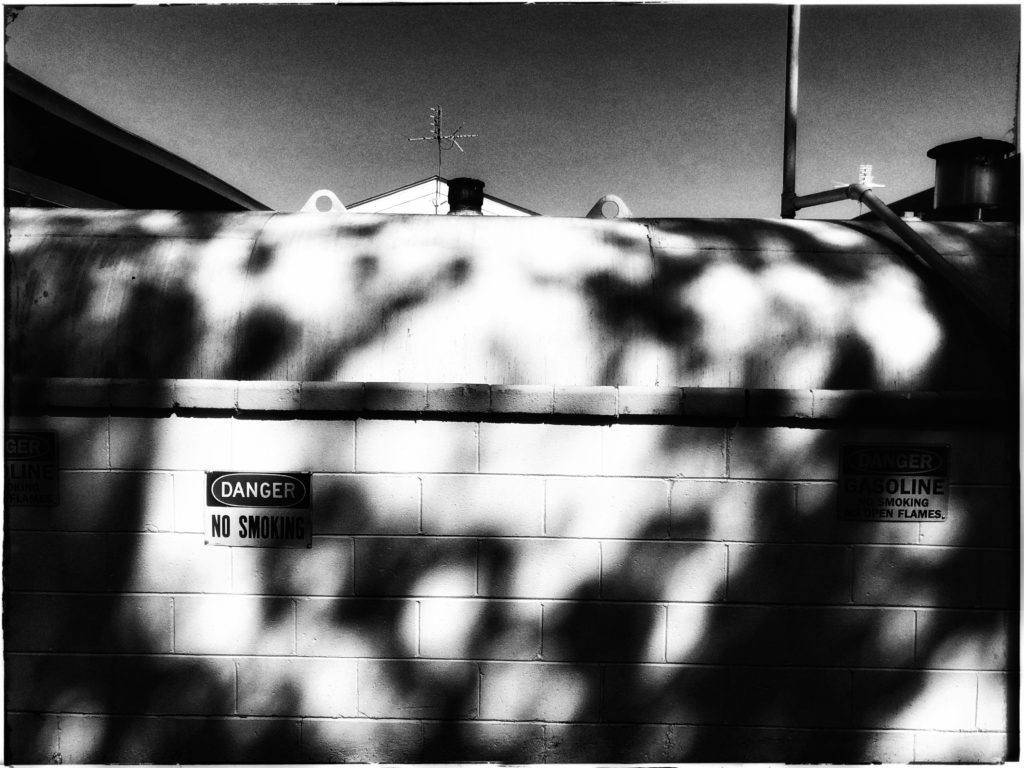

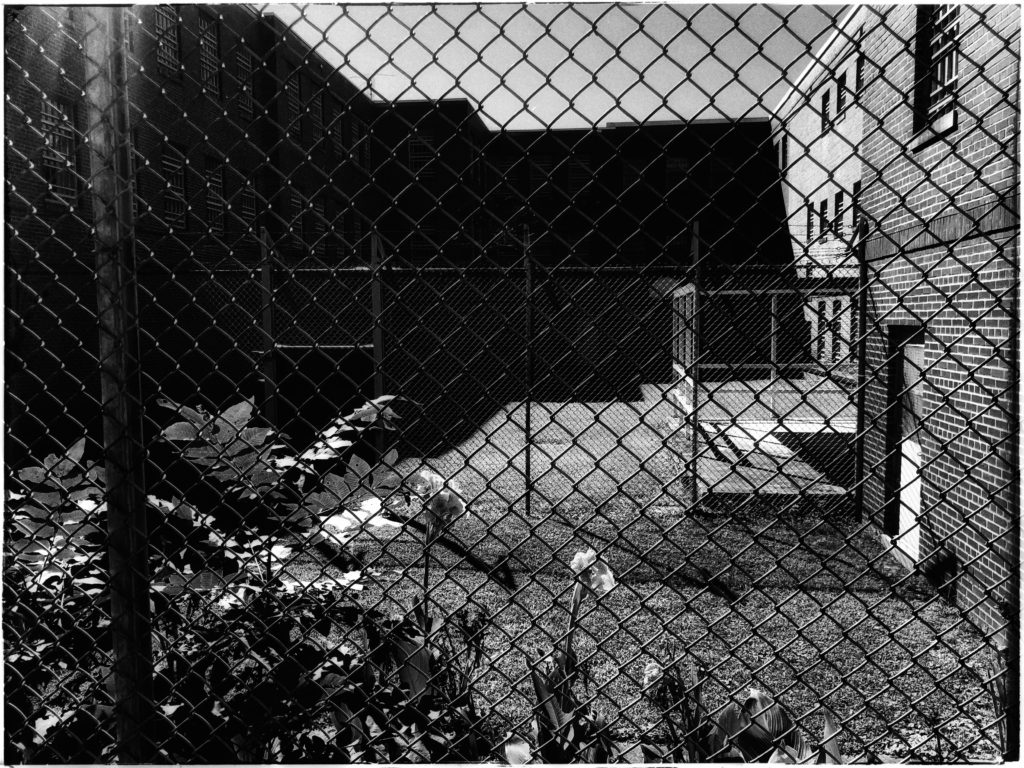

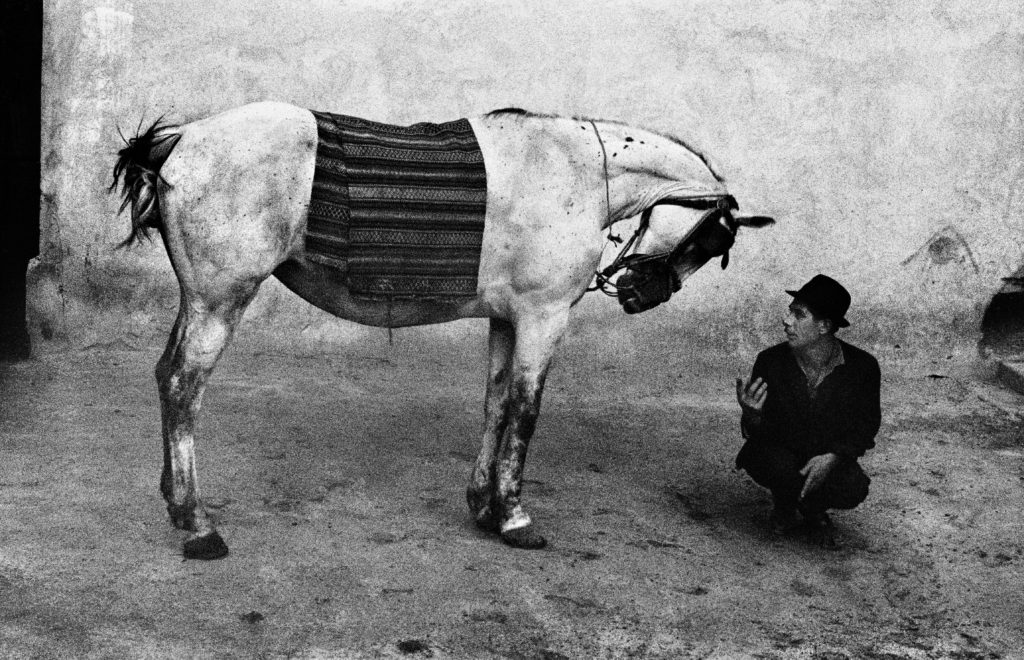

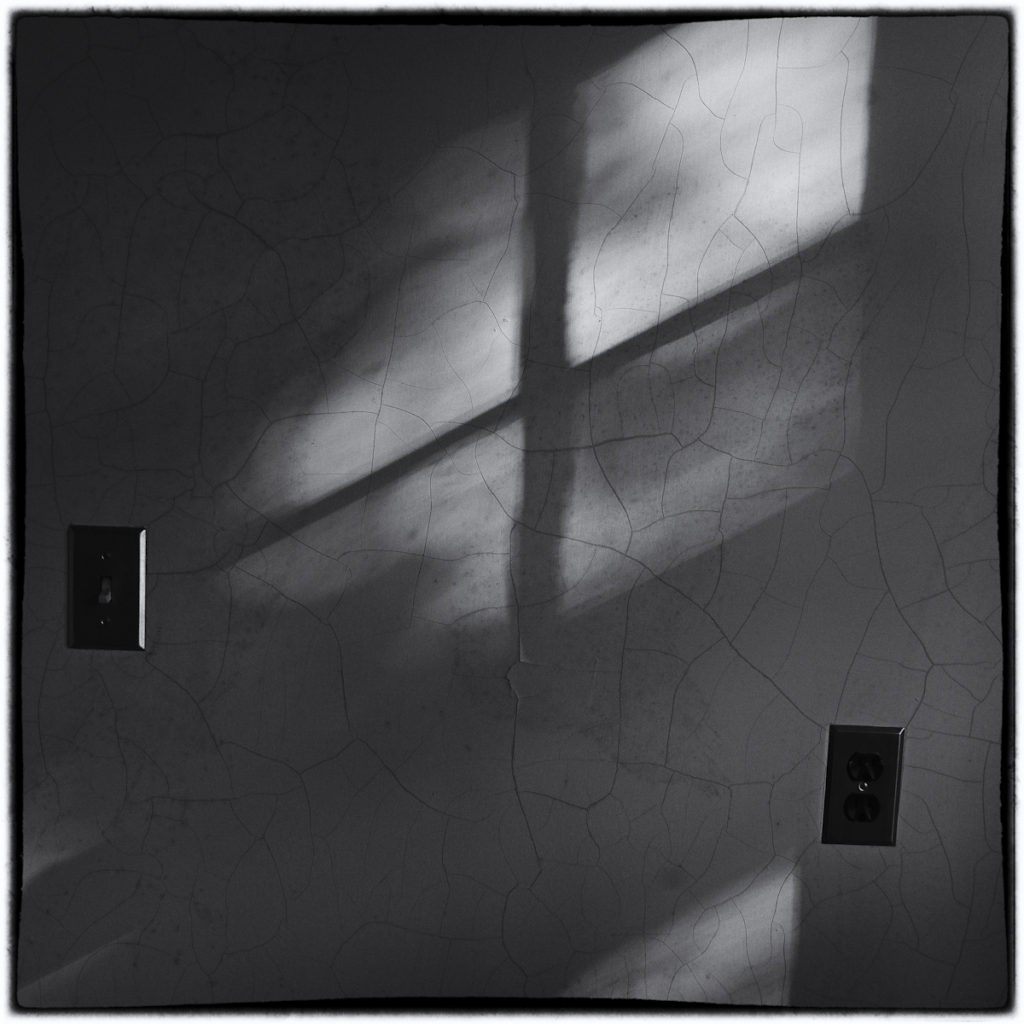

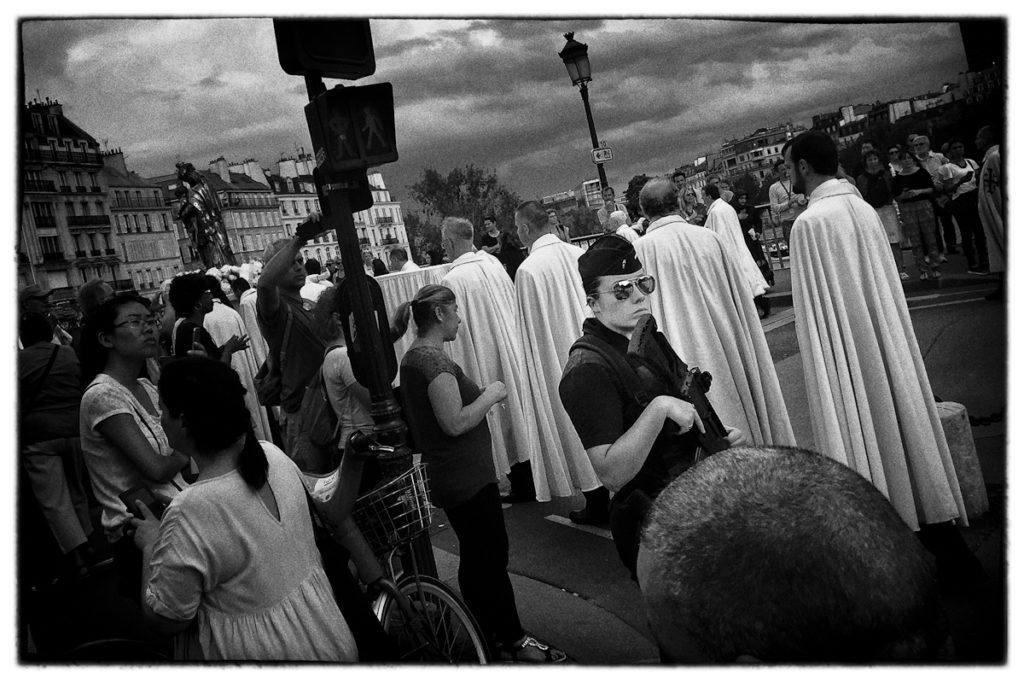

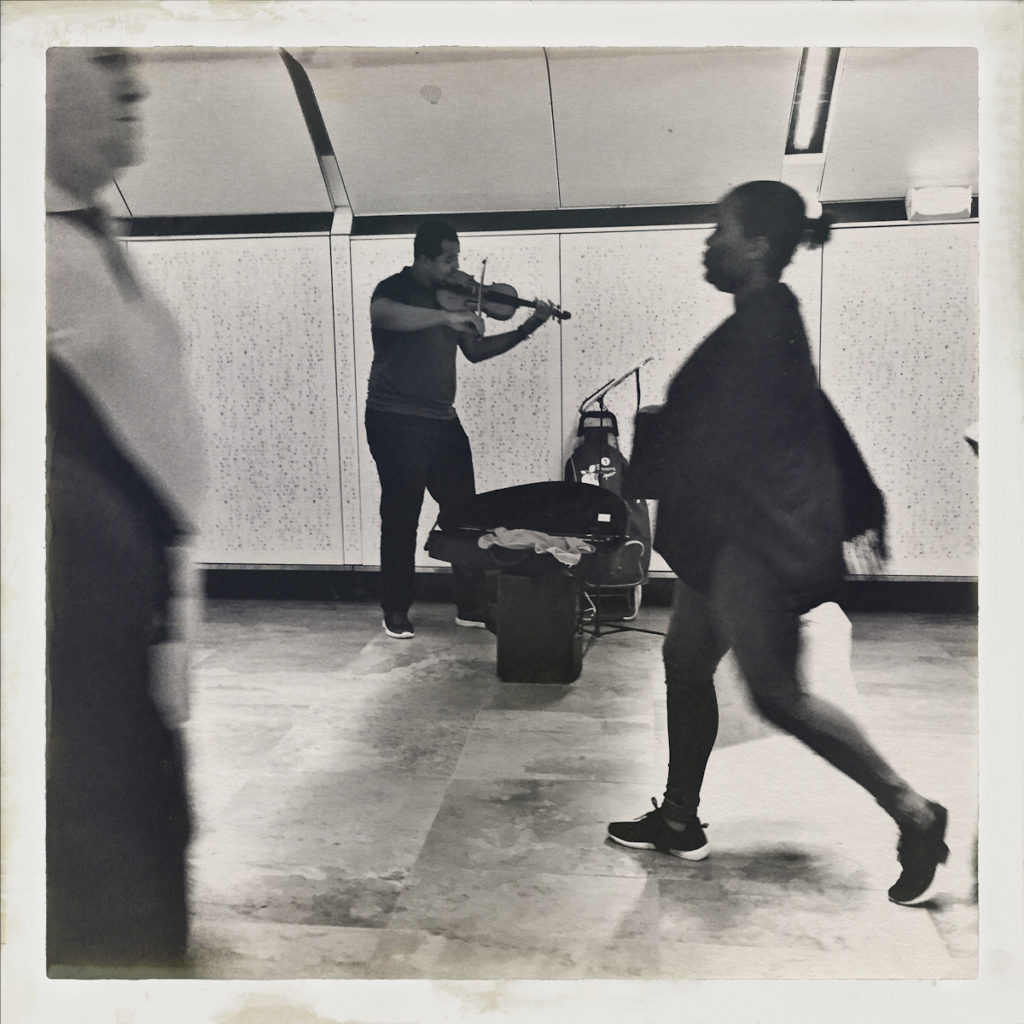

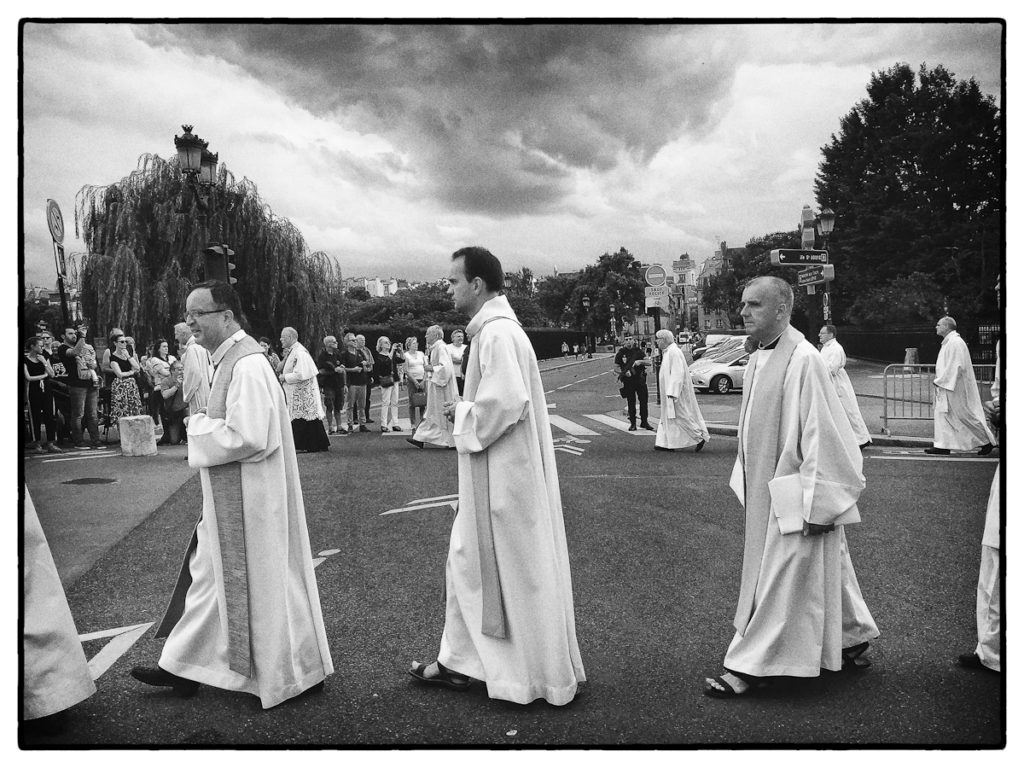

Why the new use of photography as practiced by these men and their successors Cartier Bresson, Walker Evans, Robert Frank, Josef Koudelka? As Benjamin noted, as a means of mechanical reproduction of nature, the photographic process removed the necessary subjectivity inherent in previous ‘artistic’ approaches to creating imagery, which by its very nature relied on the artist’s subjectivity to render. With a camera, that subjectivity was nullified; the camera recorded what it recorded (of course this doesn’t account for the fact that someone has to point the camera at something). What we’re given is an objective view, using Sontag’s words, “stenciled from the real.” While photographers may editorialize to the extent they choose certain subjects and present them in certain ways, photography’s objectivity assures us that what we’re seeing is real, it happened, and as a result we can draw various conclusions about the state of affairs it represents.

Is this type of photography still available to us in the digital age? I’d argue it isn’t, and this is one of the enduring conundrums photography must face as it goes forward. Photography is no longer mechanical reproduction, which Benjamin saw as the means by which it achieved its claim to objectivity. Ironically, Benjamin anticipated this devolution back to subjective imagery. In his view, history was not a linear story of progress where we learn from the past, but rather something chaotic and contradictory in which past mistakes are repeated by future generations. Digital technology has made photography endlessly maleable and as such has brought it back to the subjective status Benjamin identified as the defining characteristic of pre-photographic imagery. The objective link has been severed. If you use Benjamin’s criterion of truth, photography as an objective chronicle of the truth is dead.

.