The M8. I Had a Love/Hate With This Camera for Many Years

As you know, I’ve been, at best, ambivalent about Leica in the digital age. I’ve taken a lot of cheap shots at their digital cameras over the years, M digitals included. I’ve been skeptical that the Leica M film experience could be transposed to the digital age. Part of the problem is digital capture simply doesn’t lend itself to simplicity – it requires electronics and LCD screens and nested menus and all the afflatus that gives rise to digital bloat, and Leica isn’t immune to it in spite of their best intentions to keep things simple.

It seemed, at least in the beginning, that Leica’s continued emphasis on simplicity had become less a design ethos than a marketing slogan, or worse yet, a cynical way of attempting to paper over inferior product. It’s not like Leica, as anyone selling a widget, isn’t above self-serving puffery. Let’s face it: the M8, pleasing to look at and fondle like previous film Leicas, arrived with some serious issues: buggy electronics, color capture issues, battery problems, dismal ISO capabilities, a shutter that sounded like a construction-grade staple gun. The M9 fixed some of it, but I couldn’t help but think that Leica was over their heads in the digital age, where quality had less to do with traditional Leica hand-craftsmanship and more with technical expertise, technical expertise being the forte of large manufacturers like Nikon and Canon.

*************

And then there was the Leica ergonomic, the felt experience of operating one that was so seductive with their film M’s. The film M’s just feel right. Refined yet simple. No intercession of electronics to do things for you (before the M7 at least). Radically minimalist design, uncluttered viewfinder, big bright mechanical rangefinder. Simple wind-on, imperceptible shutter click, rewind. Advancing the film offered just enough throw and resistance to make the act pleasurable as its own experience. Many Leicaphiles carried our M’s around the house with us – why? because they stimulated that part of the lizard brain connected to the hand. Film M’s made you a gearhead.

I’m not sure that ergonomic simplicity transfers over to the digital M’s, or at least I was skeptical at best. While my M8 looked like an M it didn’t feel like one. Whatever magic they packed into the M4 was simply not there in the M8. Where the M4 felt fluidly effortless and simple, the M8 felt clunky and convoluted. Where the M4 shutter whispered, the M8 sounded like it was shooting high-velocity projectiles. Figuring out how to format a card or change ISO invariably devolved into multi-thumb fumbling of wheels, buttons, and menu options, all while your subject fleeing as if from a school shooter. Efficient it wasn’t.

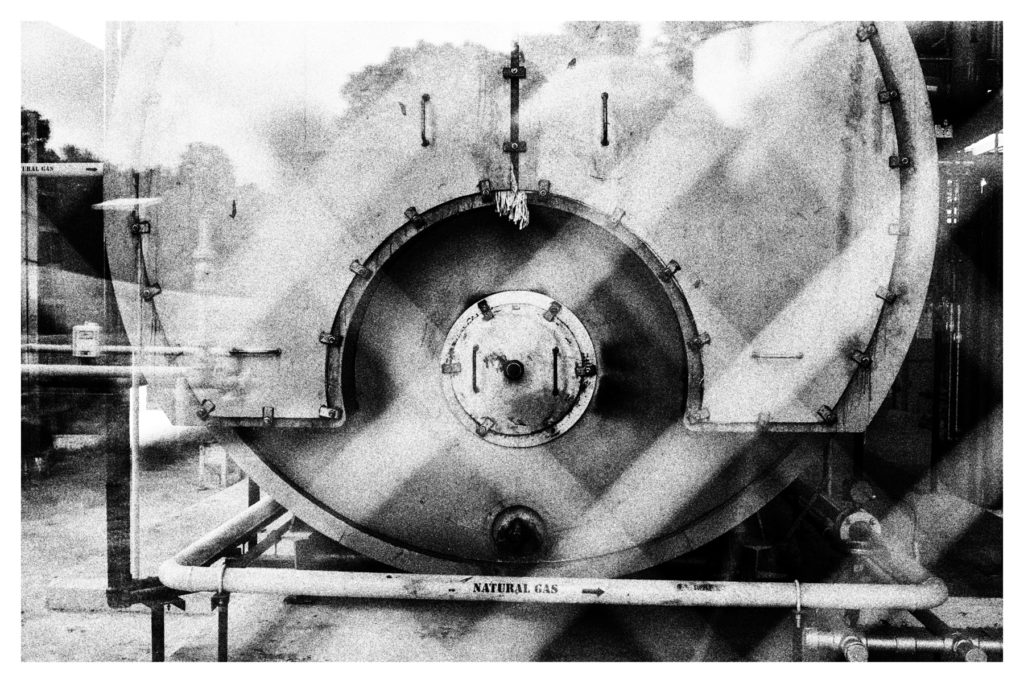

But …. if your interest was traditional B&W photography, as opposed to digital hyper-realism, in spite of what sensor rankings and 100% cropping geeks declaimed, the M8’s output was astonishing. B&W from the M8 just had the look, a function of the CCD sensor and its increased IR sensitivity which produced thick, film-like B&W files. All you needed to do was add a bit of grain. I was willing to put up with the quirks – the random freeze-ups, the glacial boot-up times, the god-awful swack of the shutter – to get that B&W output. It was that good, a monochrome camera to rival the Monochrom.

*************

This is all prelude to the fact that I’m having to rethink my opinions these days [shock!]. I bought a used M240 a while ago, not expecting much, and found that I really liked it, as in really. Wanting a digital camera to compliment my aging GXR and my exasperating Sigma SD Quattro (another love/hate thing), I’d thought of the usual alternatives – an X100, X-Pro, D4s – and then decided against them. It was time to buy a digital M.

To make a long story short – I liked the M240 so much I splurged and bought the camera I’d always really wanted – the Monochrom, the original CCD version based on the M9 platform. Found a nice one with an updated, non-corrosive sensor. I’ve totally fallen in love. It’s a digital M4. It’s got the feel. Hell, it even looks just like a black chrome M4. As for output, I’m convinced there’s a roll of Ilford HP5 rated at 800 ISO hidden in there somewhere.

An M5 w/ HP5 @ 800 ISO, an M240 DNG Run Through Silver Efex … or a Leica Monochrom?

So, going forward I’ve decided to go all Steve Huff on you, amusing you with various posts about the Mono and the M240 and how they compare to an M5 with HP5. This weekend, I’m going out with the M5 and a 35mm VC loaded with HP5, the Mono and the M240 and see how they each render the same subject. If you’ll indulge my geekiness, I promise no 100% crops or duplicate shots of fence posts. I’ll try to keep shots of the wife and cats to a minimum.

Hits: 18