David Burnett, Washington Post, June 12, 2012:

It’s difficult to explain to someone who has grown up in the world of digital photography just what it was like being a photojournalist in the all-too-recently-passed era of film cameras. That there was, necessarily, a moment when your finite roll of film would end at frame 36, and you would have to swap out the shot film for a fresh roll before being able to resume the hunt for a picture. In those “in between” moments, brief as they might have been, there was always the possibility of the picture taking place. You would try to anticipate what was happening in front of your eyes, and avoid being out of film at some key intersection of time and place. But sometimes the moment just wouldn’t wait. Photojournalism — the pursuit of storytelling with a camera — is still a relatively young trade, but there are plenty of stories about those missed pictures.

In the summer of 1972, I was a 25-year-old photojournalist working in Vietnam, mostly for Time and Life magazines. As the United States began winding down its direct combat role and encouraging Vietnamese fighting units to take over the war, trying to find and tell the story presented enormous challenges. On June 8, a New York Times reporter and I were going to explore what was happening on Route 1, an hour out of Saigon. We visited a small village that had seen some overnight fighting, but were told by locals that there was a bigger battle going on a few kilometers north. There, at the village of Trang Bang, I waited and watched with a dozen other journalists from a short distance as round after round of small-arm and grenade fire signaled an ongoing firefight. I was changing film in one of my old Leicas, an amazing camera with a reputation for being infamously difficult to load. As I struggled, a Vietnamese air force fighter came in low and slow and dropped napalm on what its pilot thought were enemy positions. Moments later, as I was still fumbling with my camera, the journalists were riveted by faint images of people running through the smoke. AP photographer Nick Ut took off toward the villagers who were running in desperation from the fire.

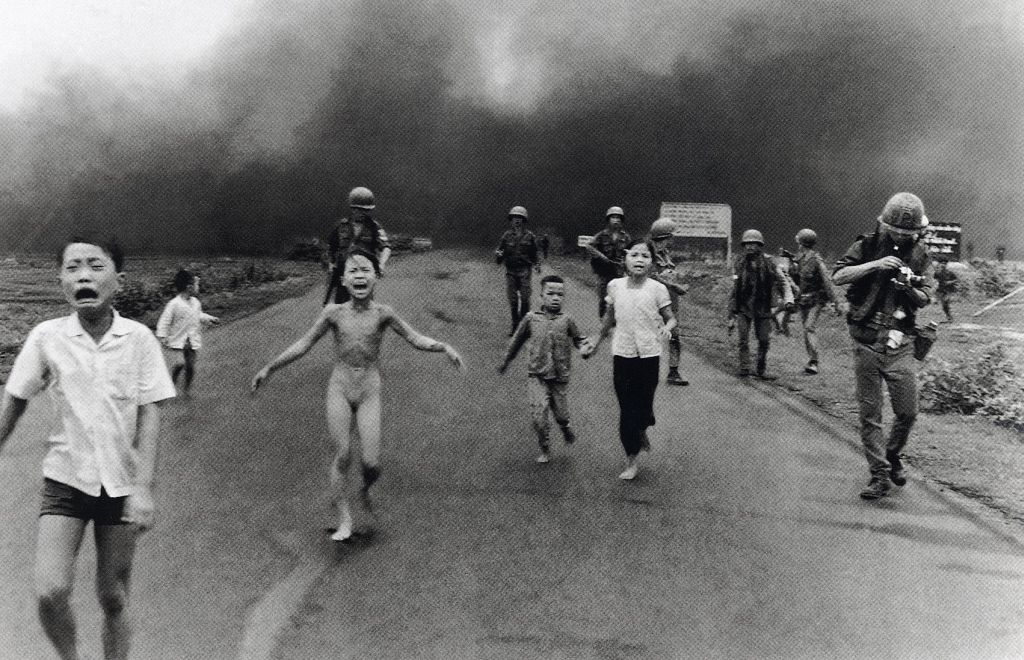

In one moment, when Ut’s Leica came up to his eye and he took a photograph of the badly burned children, he captured an image that would transcend politics and history and become emblematic of the horrors of war visited on the innocent. When a photograph is just right, it captures all those elements of time and emotion in an indelible way. Film and video treat every moment equally, yet those moments simply are not equal.Within minutes, the children had been hustled into Nick’s car and were en route to a Saigon hospital. A couple of hours later, I found myself at the Associated Press darkroom, waiting to see what my own pictures looked like. Then, out from the darkroom stepped Nick Ut, holding a small, still-wet copy of his best picture: a 5-by-7 print of Kim Phuc running with her brothers to escape the burning napalm. We were the first eyes to see that picture; it would be another full day before the rest of the world would see it on virtually every newspaper’s Page 1.

***

After Trang Bang, my sense of being “photographer ready” was more acute; the instinct has served me well in dozens of stories since. You never really know what is going to happen next. Anticipating what could happen, what might happen, those are the keys to being a great photographer.

And yet, even with those lessons uppermost in my mind, there were times when I simply didn’t anticipate what might happen.

In March 1979, having just returned days before from covering the Revolution in Iran, I found myself in a key “pool” position at the White House North Lawn. It was the official signing of the Camp David peace accords, negotiated by President Carter, between Egypt and Israel. It was a historic day, with plenty of television and photo coverage. I was carrying my own three cameras, plus one each from two other photographers, as I was given a good spot, head-on, from which to see the three dignitaries: Carter, Begin and Sadat. Once they walked onto the outdoor stage, I began shooting. I shot madly as they signed the documents and passed the papers among themselves. And at the magic moment, after they had all put down their pens, they stood up and unexpectedly embraced, hand over hand, all round, with gusts of wind fluttering the three giant flags behind them. This was the picture. As I grabbed for one of my cameras, I realized the roll was completely shot. I grabbed the next camera: same result. And then the third, fourth and last cameras. Panic. I was out of film in all five cameras, and even with motorized loading was still at least 25 or 30 seconds away from being able to make a picture.

There were no more groundbreaking handshakes. No more diplomatic embraces. It was over, and I had no pictures of that day that, to me, spoke to the event itself.

In the new digital age of 1,000-plus pictures on a memory card, running out of “film” is less likely. But being aware is still what photography is about. Being able to see that bigger world and your place in it. And knowing that, at any time, a picture could take place. So, today, I try to always have a few frames of film left, and plenty of space on my memory card. Always.

Nick Ut’s Recollections of Trang Bang

Nick Ut, 1966, Viet Nam

Nick Ut, 1966, Viet Nam

In year 7 of the war, I heard the story about heavy fighting in Trang Bang. Lots of people were fighting on highway one and they had locked down the highway. They were fighting like they were on the first day. So I told a friend of mine that I wanted to go there the next day in the early morning. At 7:30 the following morning I saw 1,000 victim refugees on the highway, many of them running. I took a lot of pictures of refugees running, and you could see the black smoke from the bombs all morning. I followed the 25th division away from the highway 2 miles away. When I went back to the highway I saw dead bodies everywhere. So I wanted to head back to AP Saigon because I had many pictures ready. That was when I noticed one Vietnamese soldier. He had thrown a smoke grenade, which erupted in yellow smoke. Then you could hear a jet come in and dive down and drop two bombs. Immediately there were two explosions. It was very noisy. And then a sky-rider dove and dropped napalm. And I shot the picture and it looked really good because I shot in black and white, not color. I took the picture and then everyone was running furiously; I had taken the picture before anyone had realized what happened. Then a woman carrying a baby came running. She is asking for help. Her grandson was dying and he was only a year old. I used my Leica to take a picture and the boy died right in front of my camera. Then I saw the naked girl, Kim, running and I ran inside right away. I took a lot of pictures. And when she passed me I saw a lot of her skin coming off. I knew she was going to die. I put my camera down on the highway and put water on her body right away. She told me no more water. I told her it was just drinking water. But she said in Vietnamese, “Too hot! Too hot! I think I’m dying”

She told her brother she thought she was dying also. But they kept running for another ten minutes and then I told her I wanted to help her. My friend from the BBC assisted with the water bottle. Then I borrowed a raincoat for her body since she was naked. I picked her up and put her in my car with all the children already inside the car. She kept telling me she was dying. I knew she was dying, but I wanted to take her to a good hospital. And the people at the hospital wanted to help her too. But the local hospital was too small. When I got there I showed them my media pass and said if these children die your picture will be on the front page tomorrow and you might be out of a job, and they were worried. Well, we got all the children into the hospital, but then I started worrying about my pictures. I held my camera and looked at it to see how many frames I had taken. I knew that number 7 would be a good shot. When I got to the AP office I told them I had a very important roll of film. I asked them to please help me develop it, so we went into the darkroom immediately. We developed all my pictures and after looking at the first photo they asked me why I shot a picture of a naked girl. I said no, it was the result of a napalm bomb. You can see it exploding. We made one 5 x7 print of it and waited for Horst to come back so we could show him the picture. I wound up talking all week about that picture. New York and Vietnam said good job. And that morning Horst and I went back to do a story about what had happened with the napalm. Later we saw Kim’s father running around looking for her. I told him she might be dying in a hospital. He screamed and then he took a small car to the hospital right away. I went back to the hospital and I saw her parents. Her father thanked me and said I saved his daughter’s life.