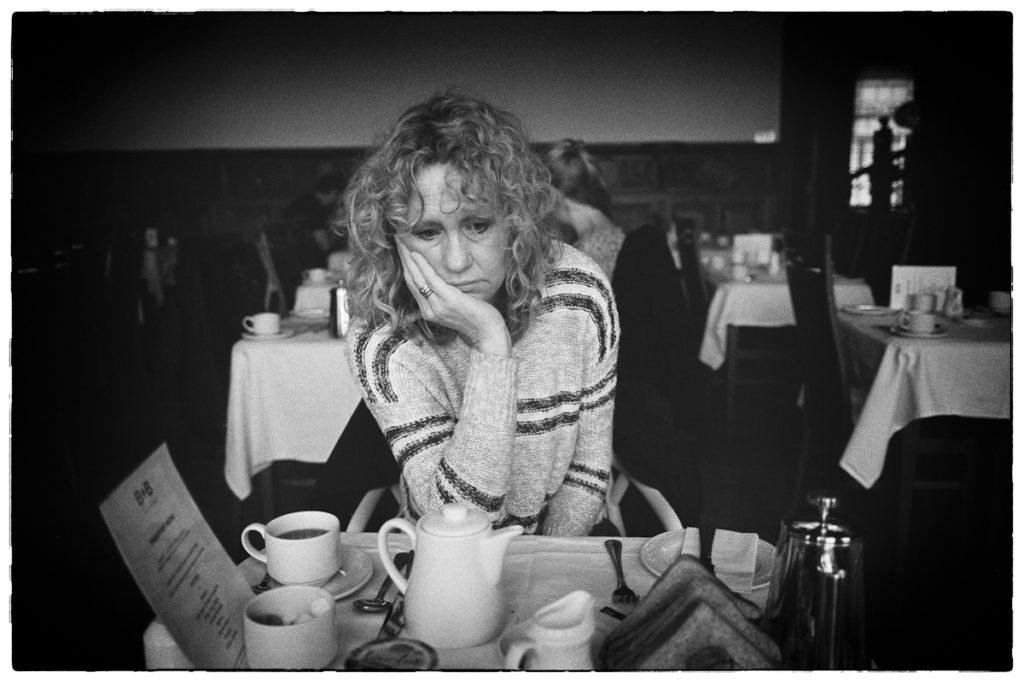

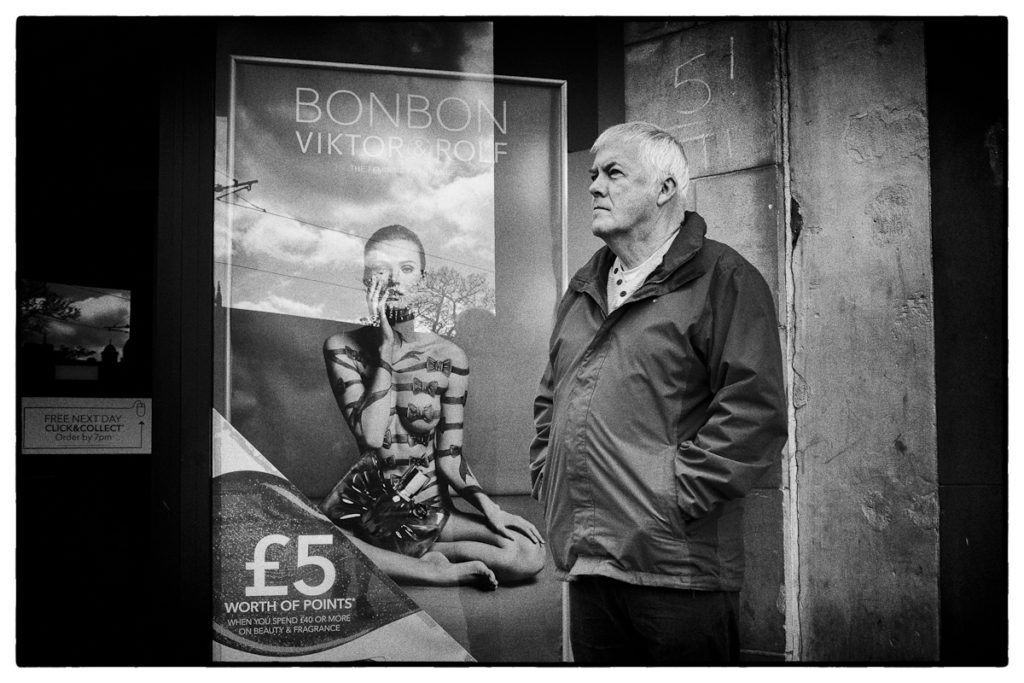

This Woman Seems Like a Nice Person, or at Least She Looks Like One

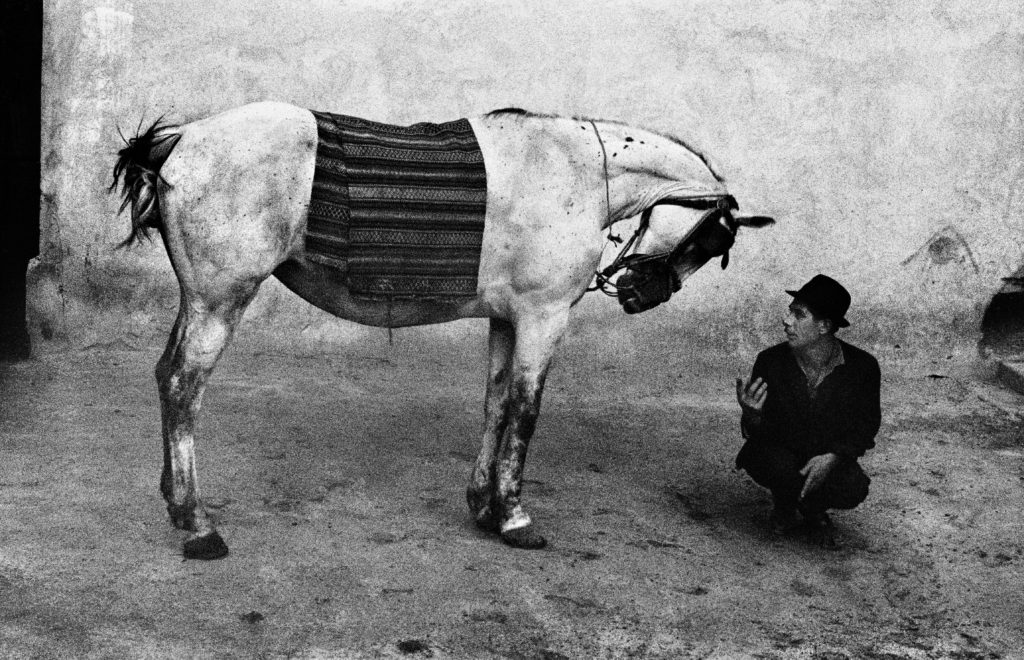

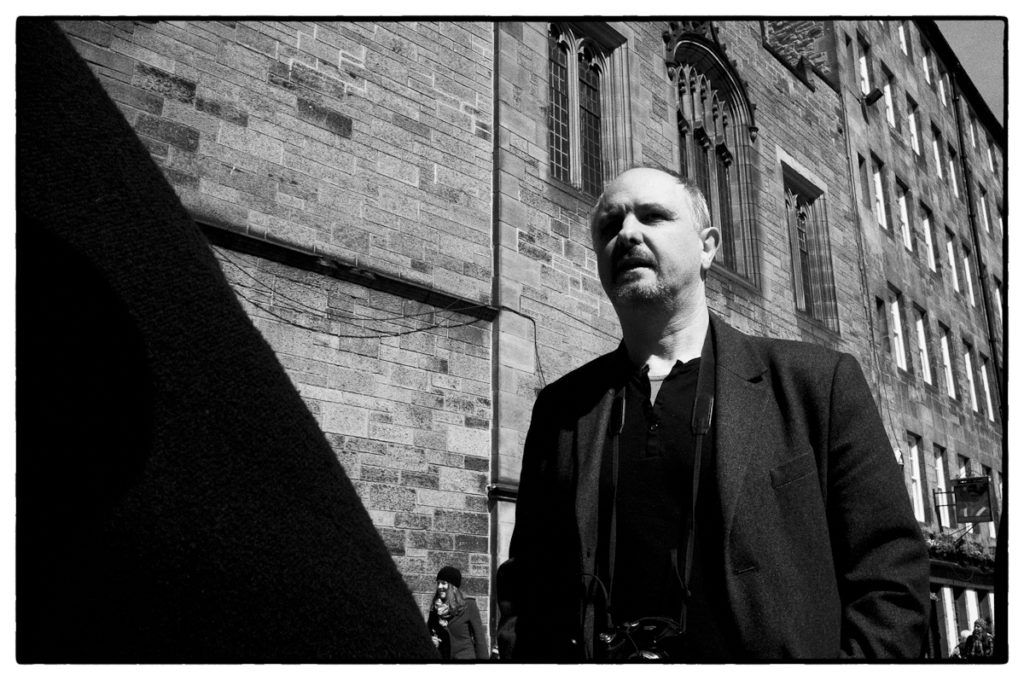

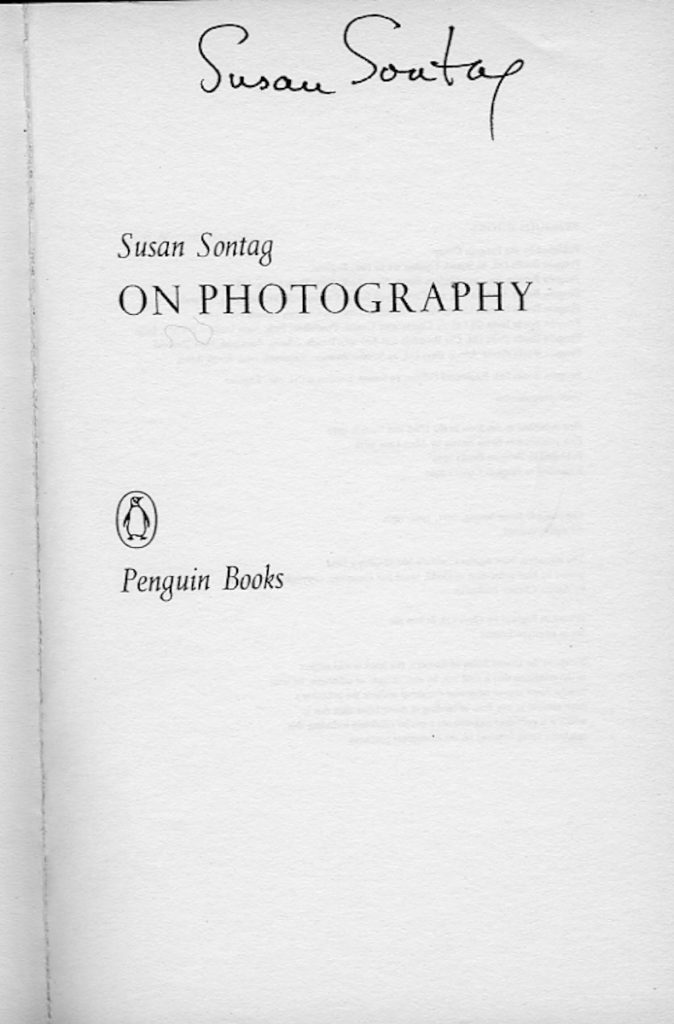

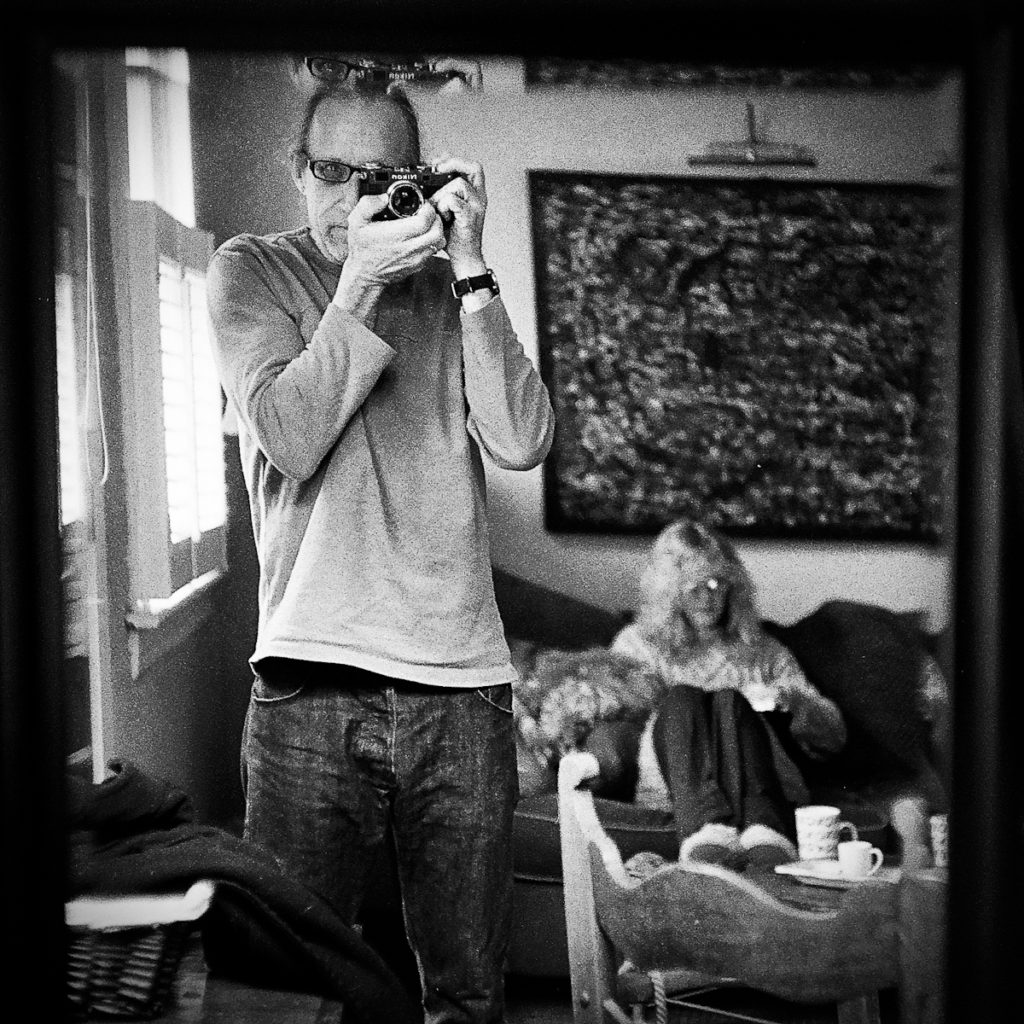

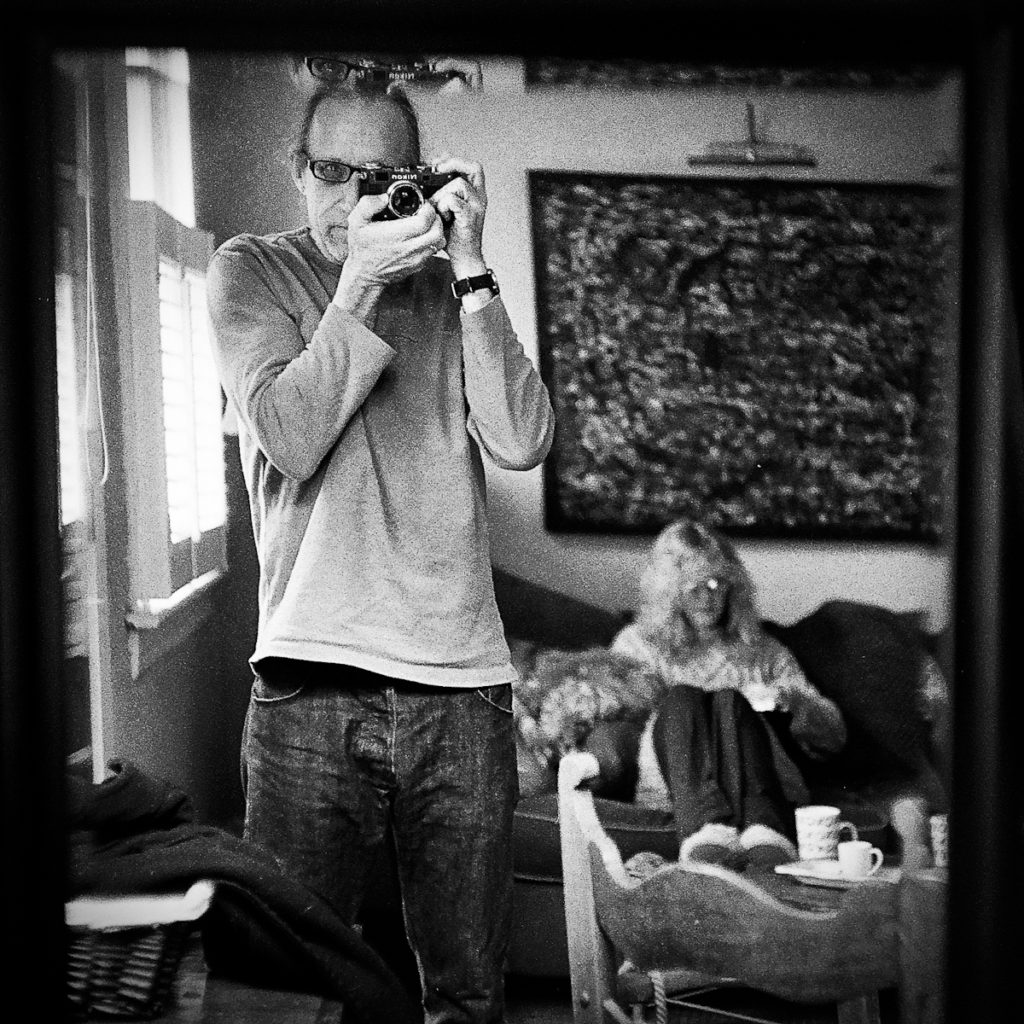

“Photographs furnish evidence,” wrote Susan Sontag in On Photography. “A photograph passes for incontrovertible proof that a given thing happened.” Sontag went on to admit that photographs might sometimes misrepresent situations, but the basic premise went unchallenged: Photos show us things that exist. It’s because of what we perceive as the photo’s truthful reliability, the “indexicality” issue we’ve beaten to death in the last post and accompanying comments. That’s a photo of me, over there; Sontag would say it’s evidence I exist. (I do.)

“Photographs furnish evidence,” wrote Susan Sontag in On Photography. “A photograph passes for incontrovertible proof that a given thing happened.” Sontag went on to admit that photographs might sometimes misrepresent situations, but the basic premise went unchallenged: Photos show us things that exist. It’s because of what we perceive as the photo’s truthful reliability, the “indexicality” issue we’ve beaten to death in the last post and accompanying comments. That’s a photo of me, over there; Sontag would say it’s evidence I exist. (I do.)

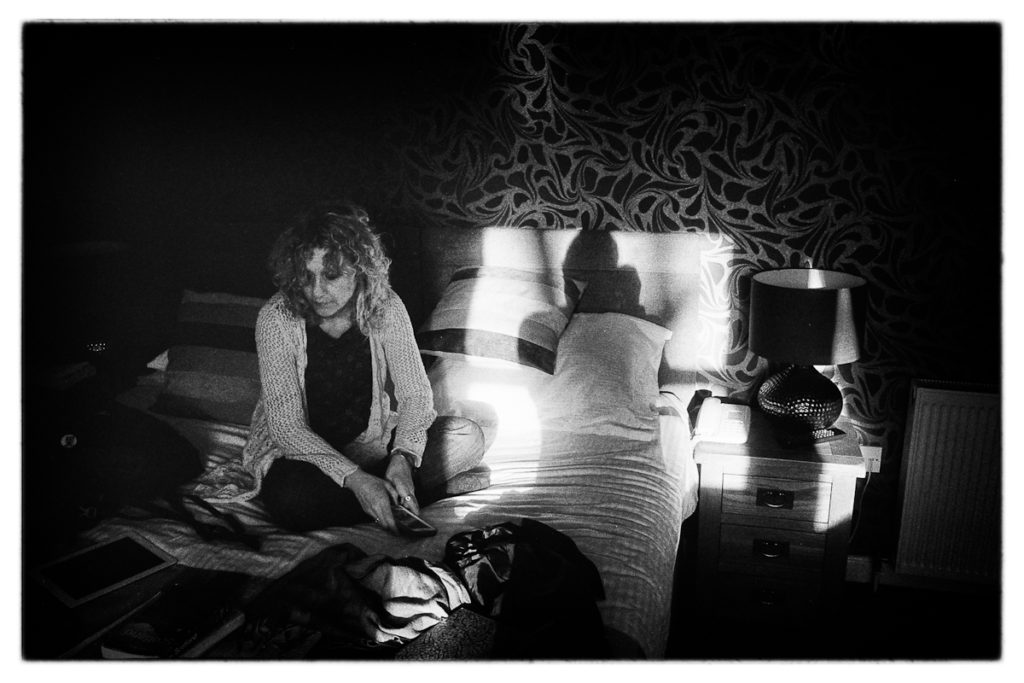

Of course, Sontag wrote in 1977, before digital photography was a thing. Now, go to the website “This Person Does Not Exist”. There you’ll see nice, unmanipulated photos of different men and women, normal looking people you’d expect to meet during your day, people just like me up there – except that the photos aren’t of real people. The people in the photos do not exist and never have existed (one of these non-existent persons is shown in the photo heading this post). Their existence has been generated via an algorithm, in this case, a “generative adversarial network” which produces original digital data [read: a new photo] from existing sets of digital data [read: 1’s and 0’s created by a digital camera]. The generative algorithm scans photos of real faces and creates new photos of new faces from them. Voila! A real photo of a fake person.

Now, take a look at that photo. If I hadn’t told you the above, if I were to tell you that was my wife, or a friend, or a family member, and that’s what she looked like, you’d believe me. All you readers arguing with me in the comments section about indexicality, you’d believe me because photos, film or digital, basically tell the truth, right? OK, it’s digital, so maybe it might have been photoshopped a bit, a few pimples removed, eyes brightened, a few crow’s feet smoothed over…but the person is real, they stood in front of someone with a digital camera, obviously they exist, and they probably look something like that. Right. You guys crack me up, unable as you are to see past the outdated conceptual blinders you wear. For those of you arguing against the idea that there really isn’t much difference between the presumed truthfulness of film versus digital photos, go to the website and look around.

*************

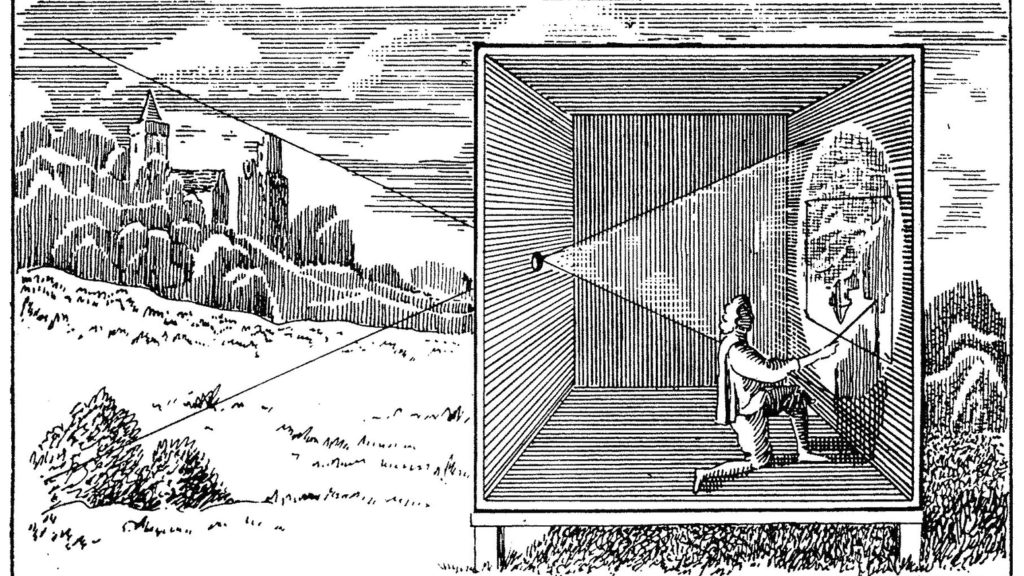

in 1945, film critic André Bazin (1918-58) wrote an essay entitled ‘The Ontology of the Photographic Image’. ‘Ontology’ is a word you’ll see a lot in philosophy. It’s the study of the ultimate “being” of a thing (e.g. “What do we mean when we say a thing is an animal?”). To discuss the ontological status of photography is to consider what particular kind of thing a photograph is. Kazin’s interest in the ontology of photography leads to Susan Sontag (On Photography, 1977) and Roland Barthes (Camera Lucida, 1980).

I’ve already discussed Barthes at length elsewhere. In Camera Lucida, Barthes employed a philosophical method associated with Jean-Paul Sartre called “phenomenology”, Barthes himself noting the book was written “in homage to L’Imaginaire by Jean-Paul Sartre.” Sartre wrote L’Imaginaire in 1940, a few years before Kazin’s essay, wherein he applied the ideas of Edmund Husserl, the founder of phenomenology, to investigate various kinds of images, including photographs.

Sartre’s point in L’Imaginaire is that there are different kinds of apprehending, correlated with different kinds of objects. Sartre says that when looking at photos we must “intend pictorially”; i.e. apprehending something as a picture is different from apprehending something as a simple object. “If it is simply perceived, [the photo] appears to me as a paper rectangle of quality and, with shades and clear spots distributed in a certain way. If I perceive that photograph as ‘photo of a man standing on steps’, the neutral phenomenon is necessarily already of a different structure: a different intention animates it.” That’s classic phenomenology, where every conscious experience has “intentionality,” which is a fancy way of saying that everything we think is shaped by the category we place the thing thought about.

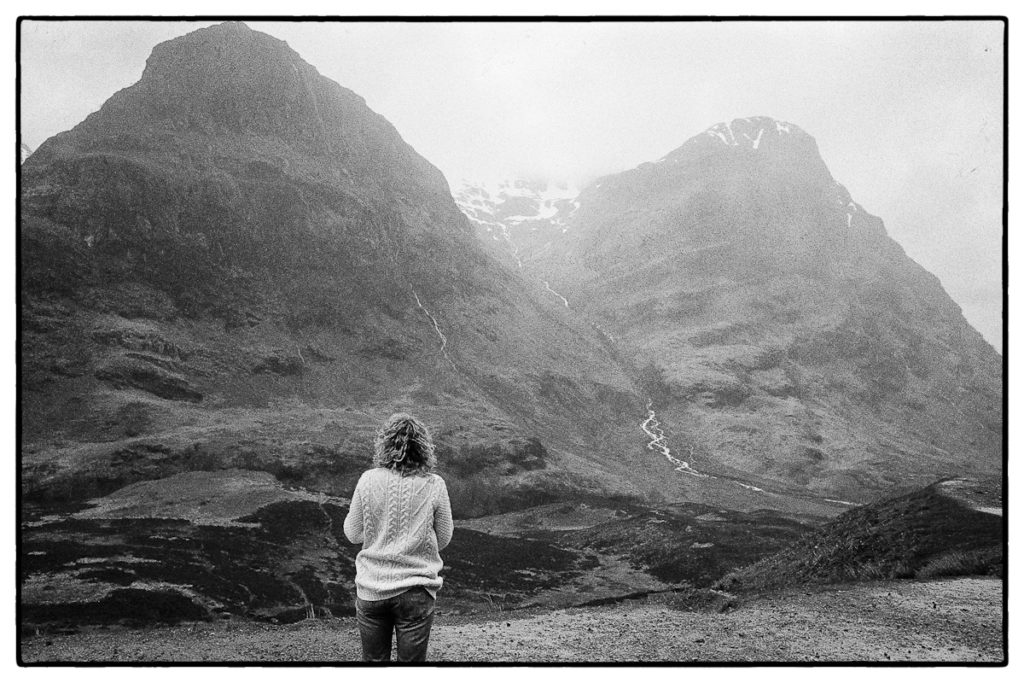

Barthes, following Sartre, notes the difference involved in perceiving a photo versus perceiving it as a photo. For Barthes the essence of perceiving something as a photograph is ‘that-has-been’: “In photography,” he writes, “I can never deny that the thing has been there”. The person in the photo exists, Barthes is saying; the photo is the proof. By contrast, no painted portrait can compel me to believe its subject had really existed. Hence “This-has-been; for anyone who holds a photograph in his hand, here is a fundamental belief… nothing can undo unless you prove to me that the image is not a photograph.”

So, what of the analyses of Bazin, Sartre, Sontag, and Barthes in the digital age? I’ve discussed the implications of Barthes’ thought here. Listen again to what Barthes considered the ontology of photography: “This-has-been; for anyone who holds a photograph in his hand, here is a fundamental belief… nothing can unless you prove to me that the image is not a photograph.” Using this definition, a digital photograph is not a photograph in Barthes’ sense of the word. This is true of all digital photos, and not just the real images of fake people on “This Person Does Not Exist,” because the necessary connection to the real thing photographed has been severed and replaced by its connection with a string of 0s and 1s stored in a computer file. With the onset of the digital age, in the words of William Mitchell, there is now “an ineradicable fragility of our ontological distinctions between the imaginary and the real.”

*************

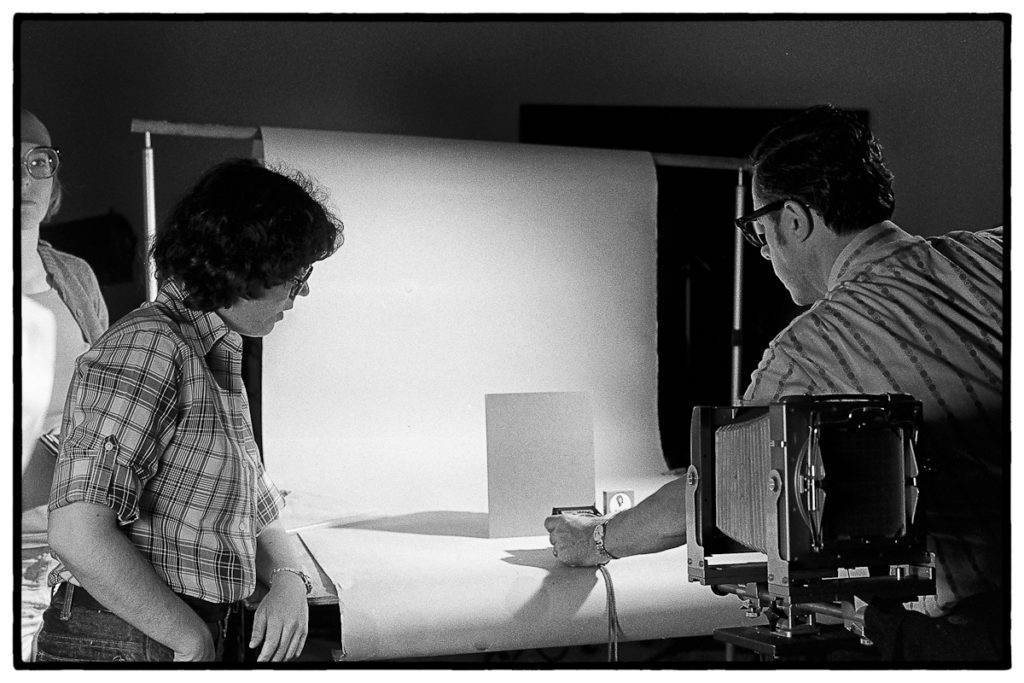

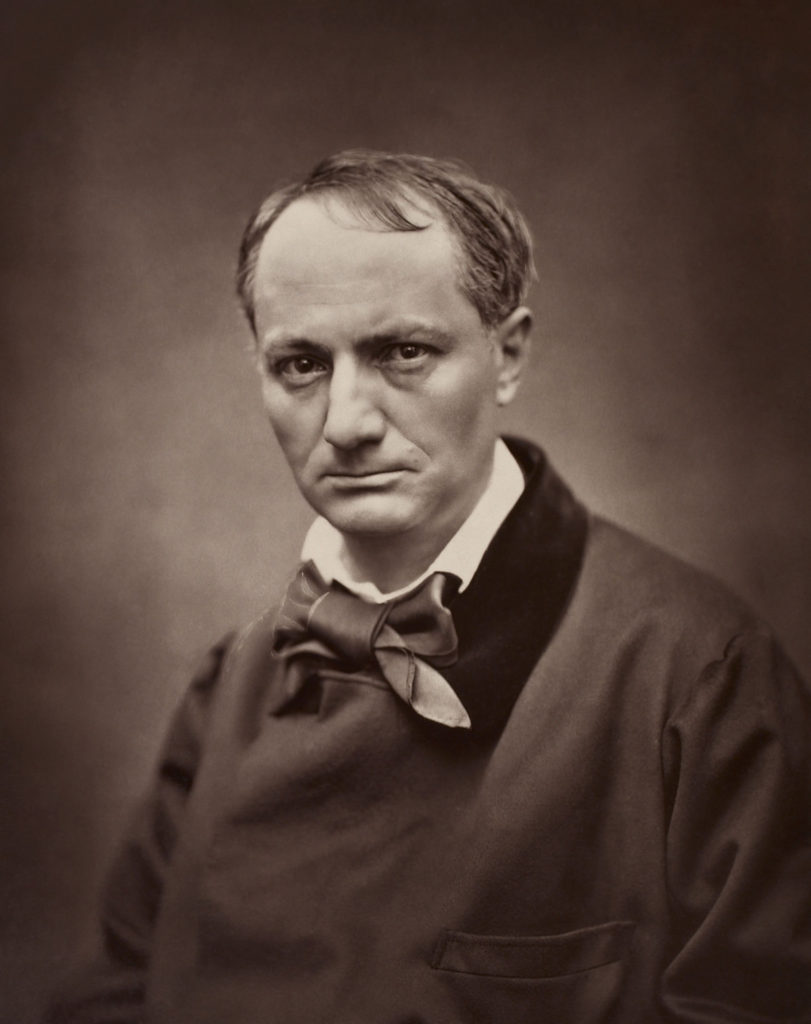

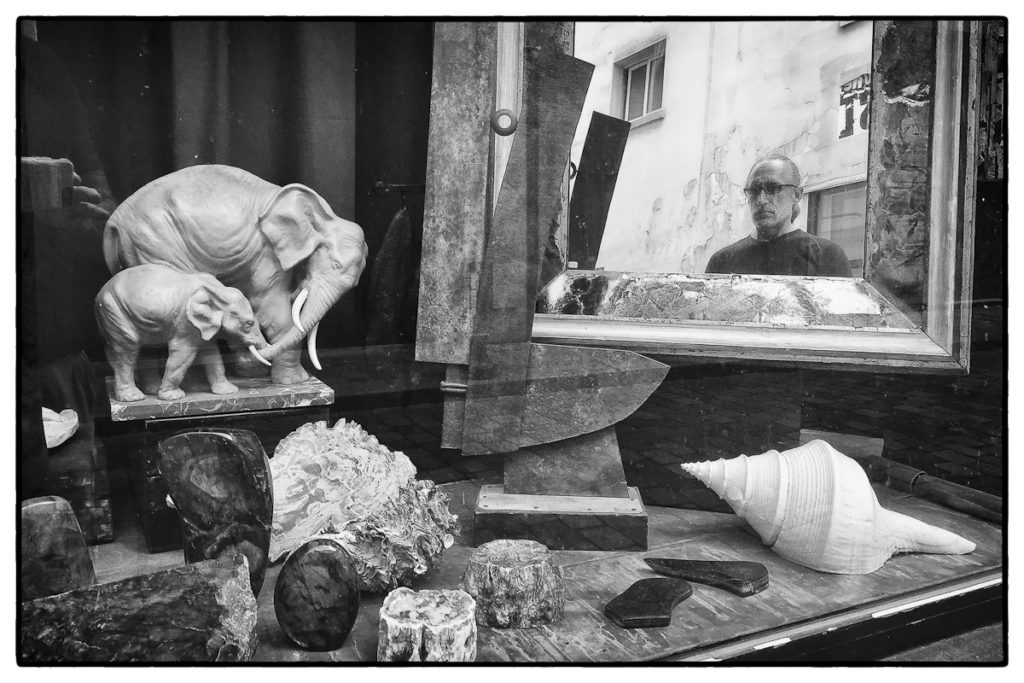

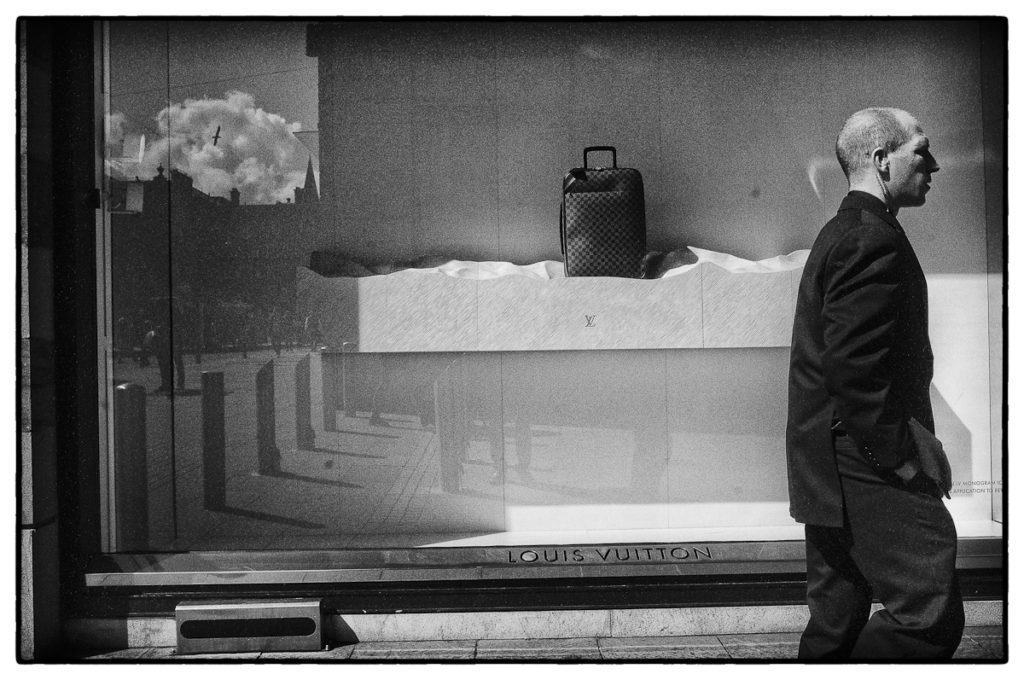

Jean Baudrillard, Enjoying a Gitanes While Thinking Deeply

So, if digital images are not photographs in the traditional sense, what is their ontological status – what kind of thing are they? According to Jean Baudrillard (1929 – 2007), French philosopher, cultural theorist, political commentator… and photographer, digital images are “simulacra.” Baudrillard was a Semiotics guy like Barthes, who wrote about diverse subjects, including consumerism, gender relations, economics, social history, art, Western foreign policy, and popular culture. He is best known, however, for his thinking about signs and signifiers and their impact on social life, in so doing popularizing the concepts of simulation and hyperreality. And, luckily for us, he was minimally aware enough of his surroundings not to get run over by a truck, like Barthes, and so lived to see the digital age.

Baudrillard’s post-digital world is made up of surfaces populated with self-proliferating “simulacra”, which are not copies of the real but their own thing, the hyperreal. Where classic philosophy saw two types of representation— 1) faithful and 2) intentionally distorted (simulacrum)—Baudrillard sees four: (1) basic reflection of reality; (2) perversion of reality; (3) pretense of reality (where there is no model); and (4) simulacrum, which “bears no relation to any reality whatsoever.” Digital photos are in the 4th category – simulacra – and are generated “by models of a real without origin or reality: a hyperreal. The territory no longer precedes the map… it is the map that precedes the territory. It is … whose vestiges persist here and there in the deserts that are… ours. The desert of the real itself.”

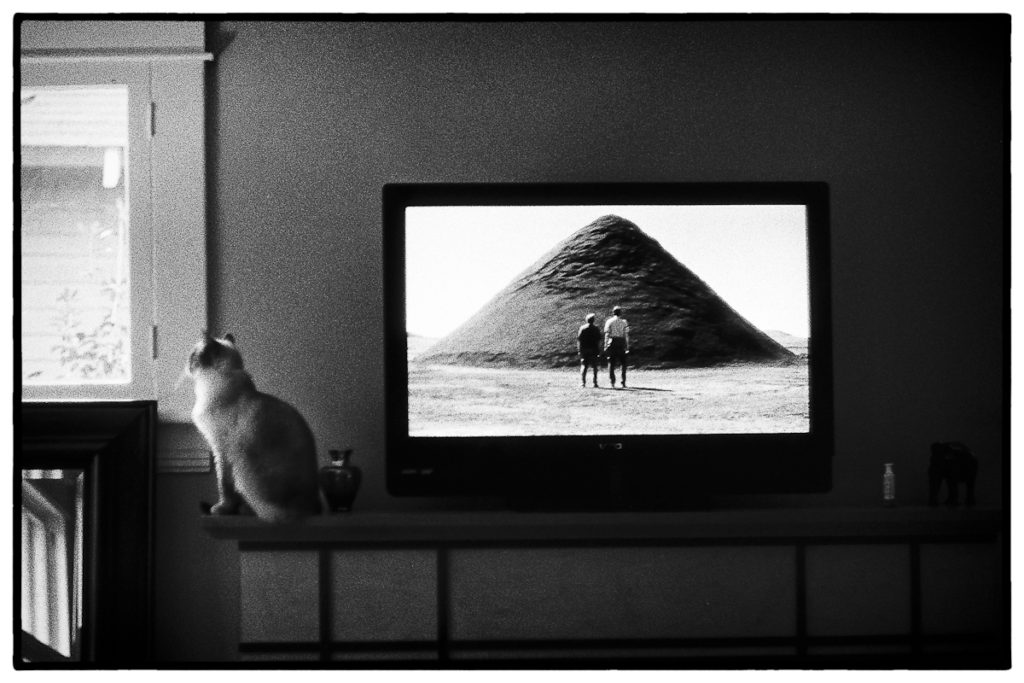

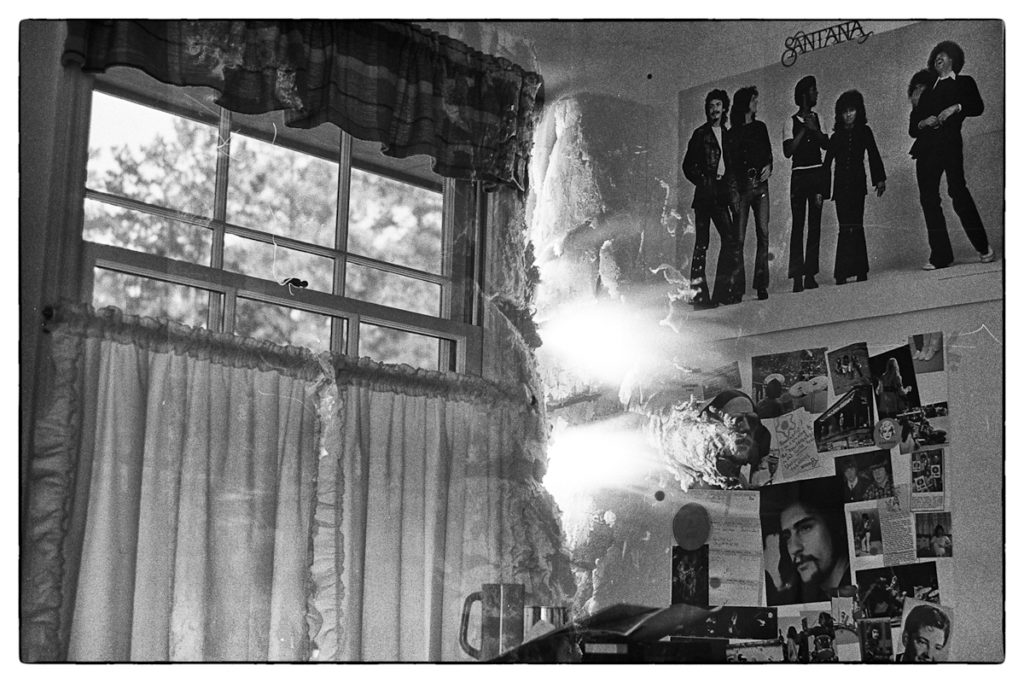

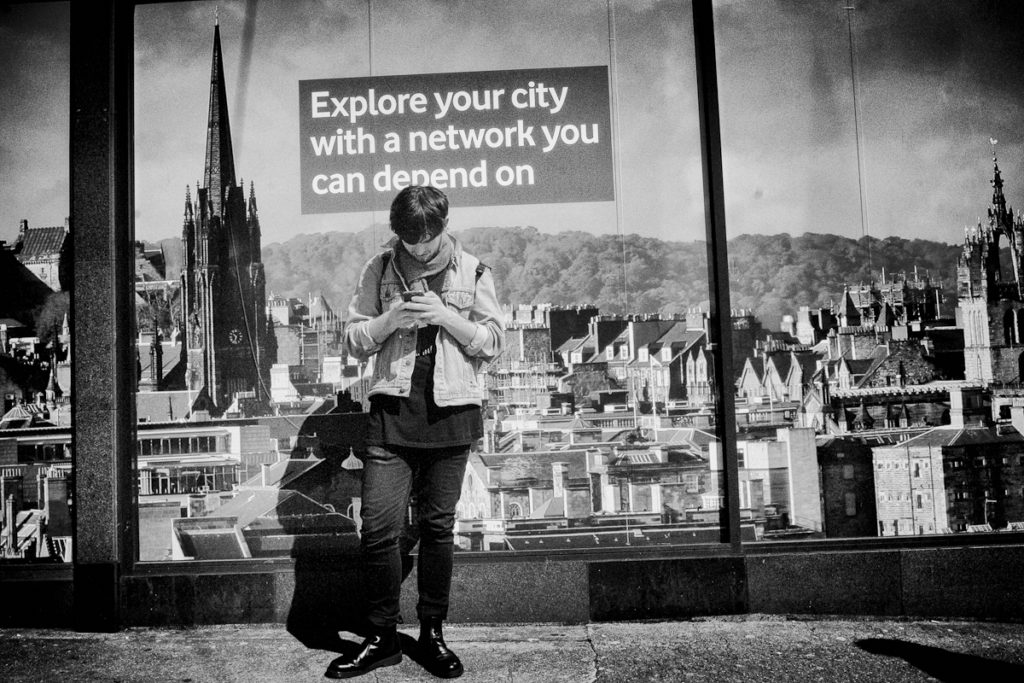

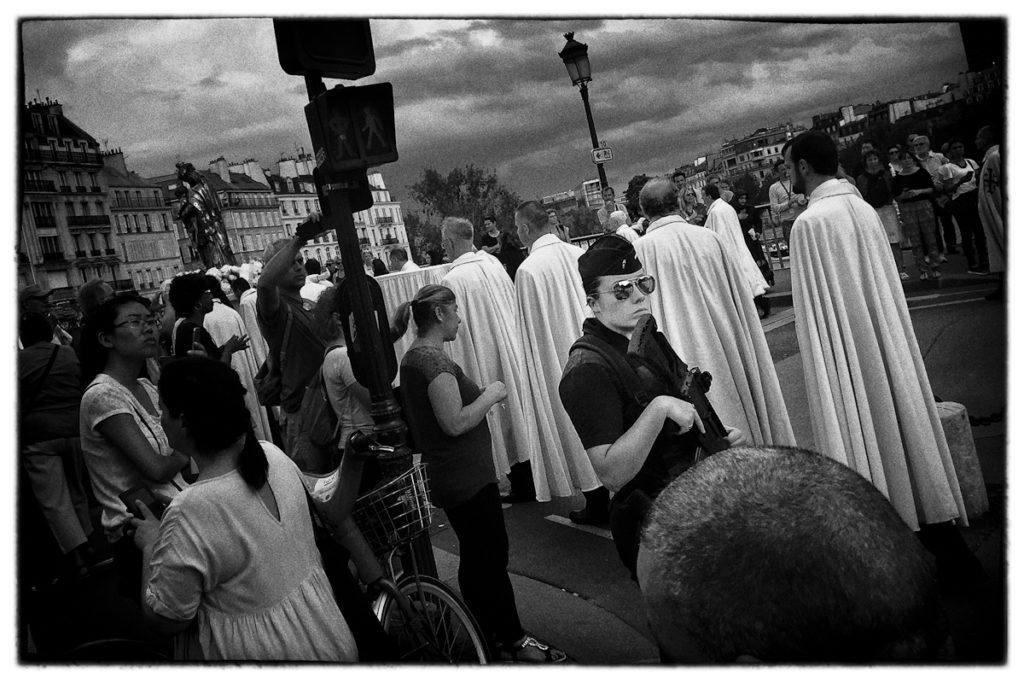

The problem with our new digital world, as Baudrillard sees it, is that our sense of reality is in the process of being inexorably altered by the endless profusion of non-reality based images, “simulacra.” In phenomenological terms, the categories we assign things to have been altered; that is to say, digitization has altered our ontology. As Sartre noted, from a phenomenological perspective, photographs form a distinctive category of objects. To see a picture as a photograph is to put it in a category. Now, for Baudrillard, to see something as a digital image is to locate it within the category of simulacra, the not-real, if only subconsciously (Baudrillard would say that we will gradually transition consciously once we’ve realized the ruse is up). This is the radical opposite of Sontag’s claim for analog photography. For Baudrillard, with digital’s severing of indexicality, we can never be certain what kind of image we are seeing, and so, by default, we must assign it to the category of simulacrum. Where once the image world provided us with windows onto reality, the image world now surrounds us in fictitious landscapes that heighten ontological uncertainty by eradicating the distinction between real and not real.

*************

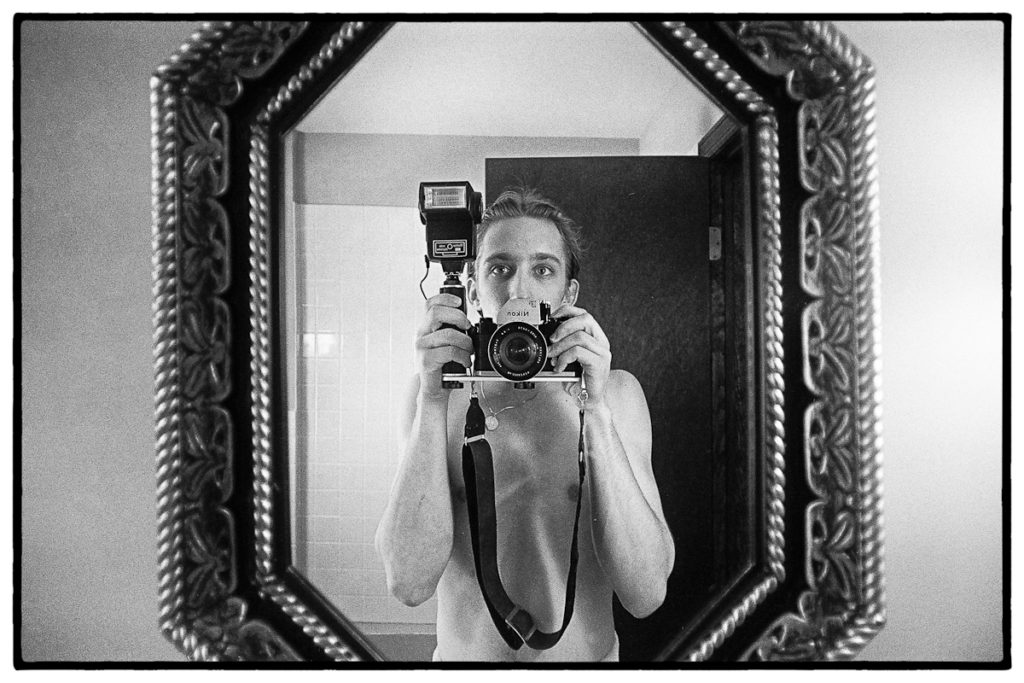

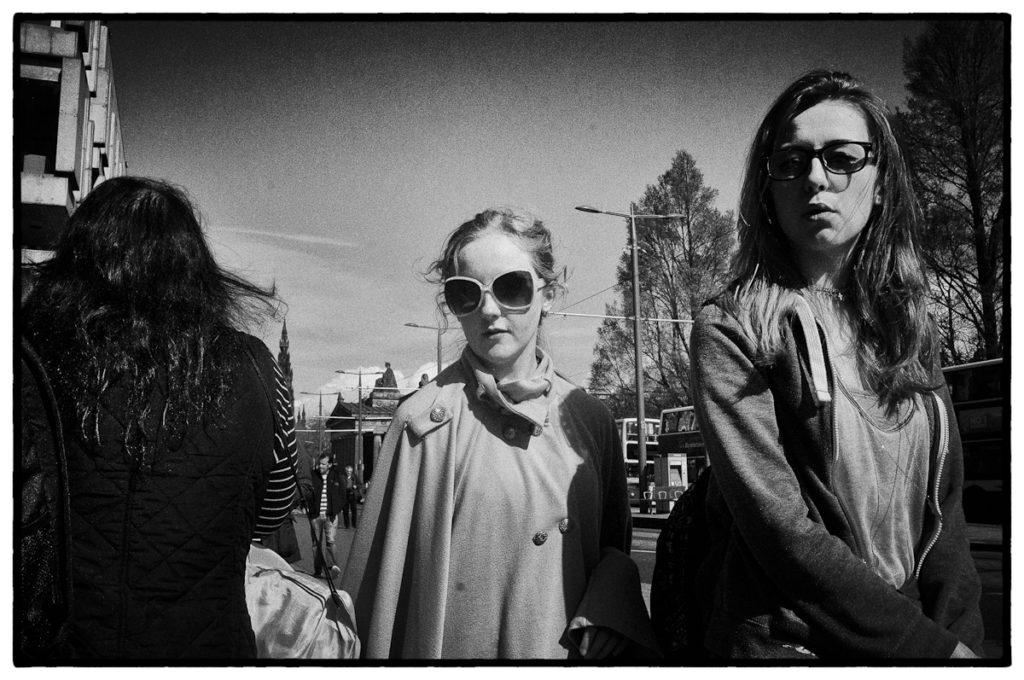

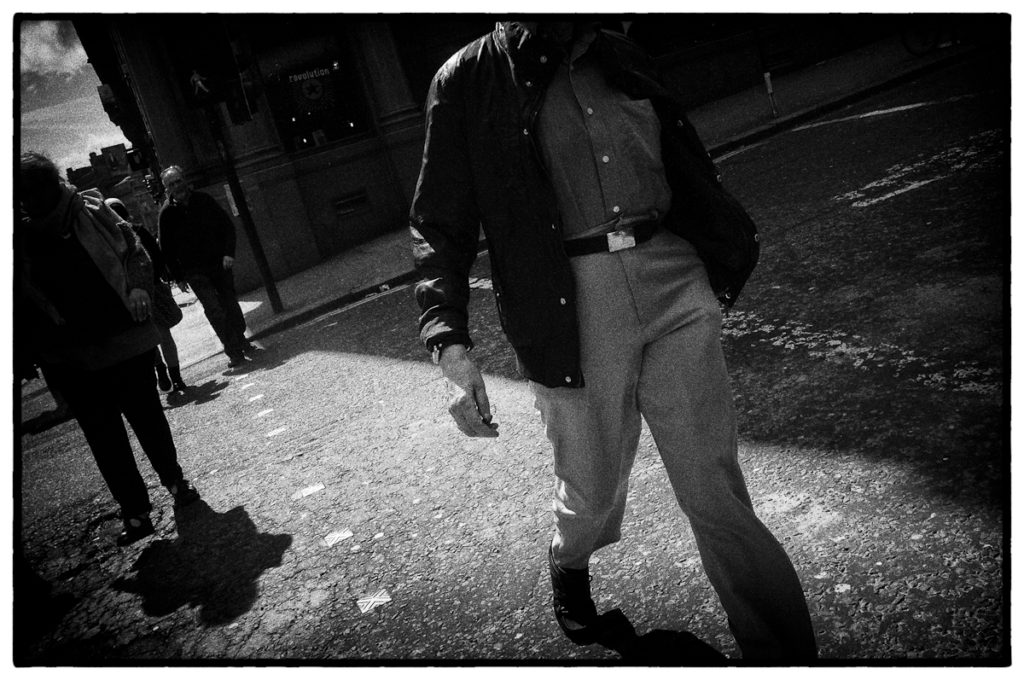

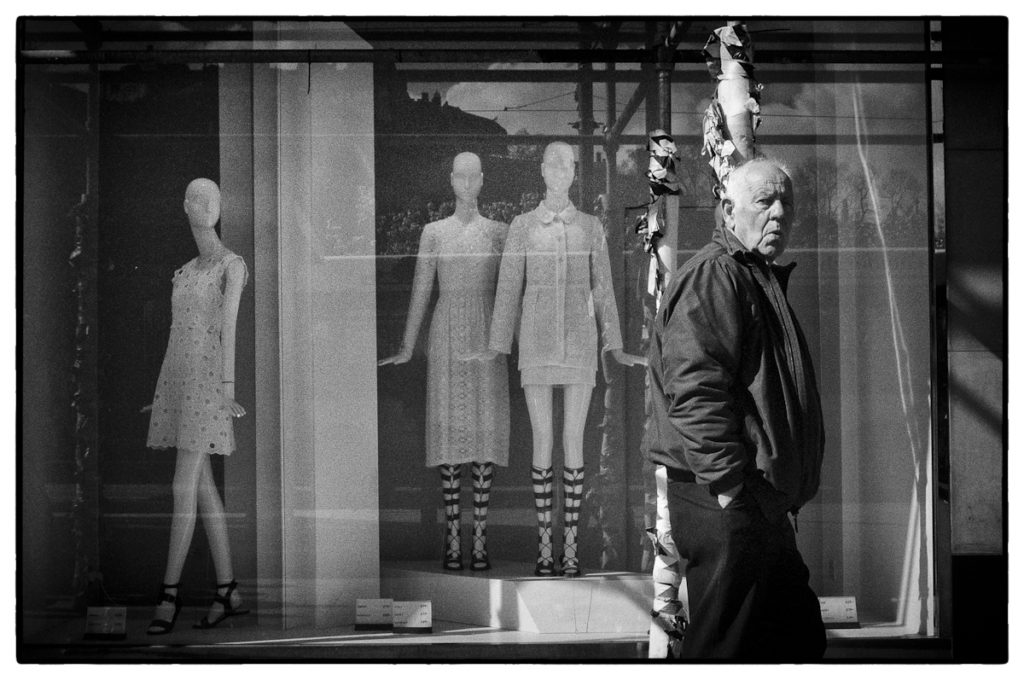

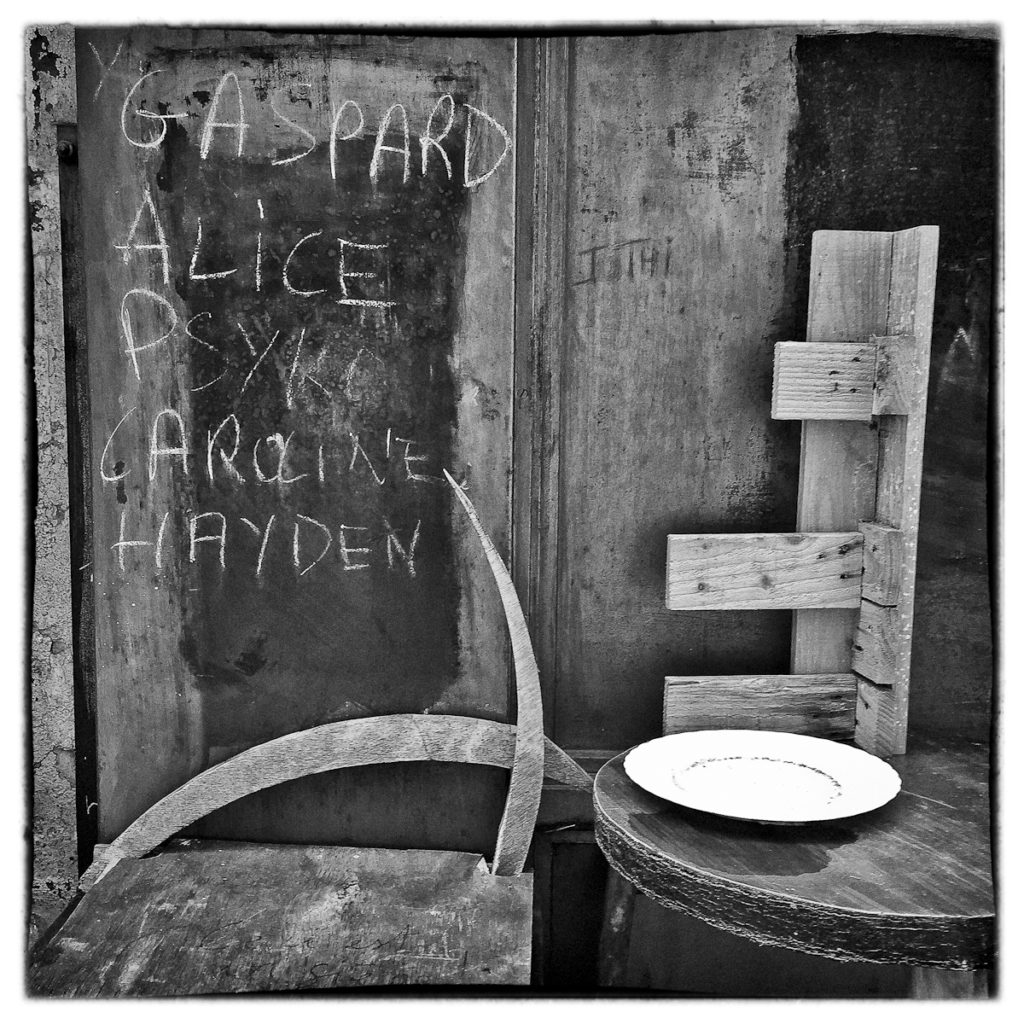

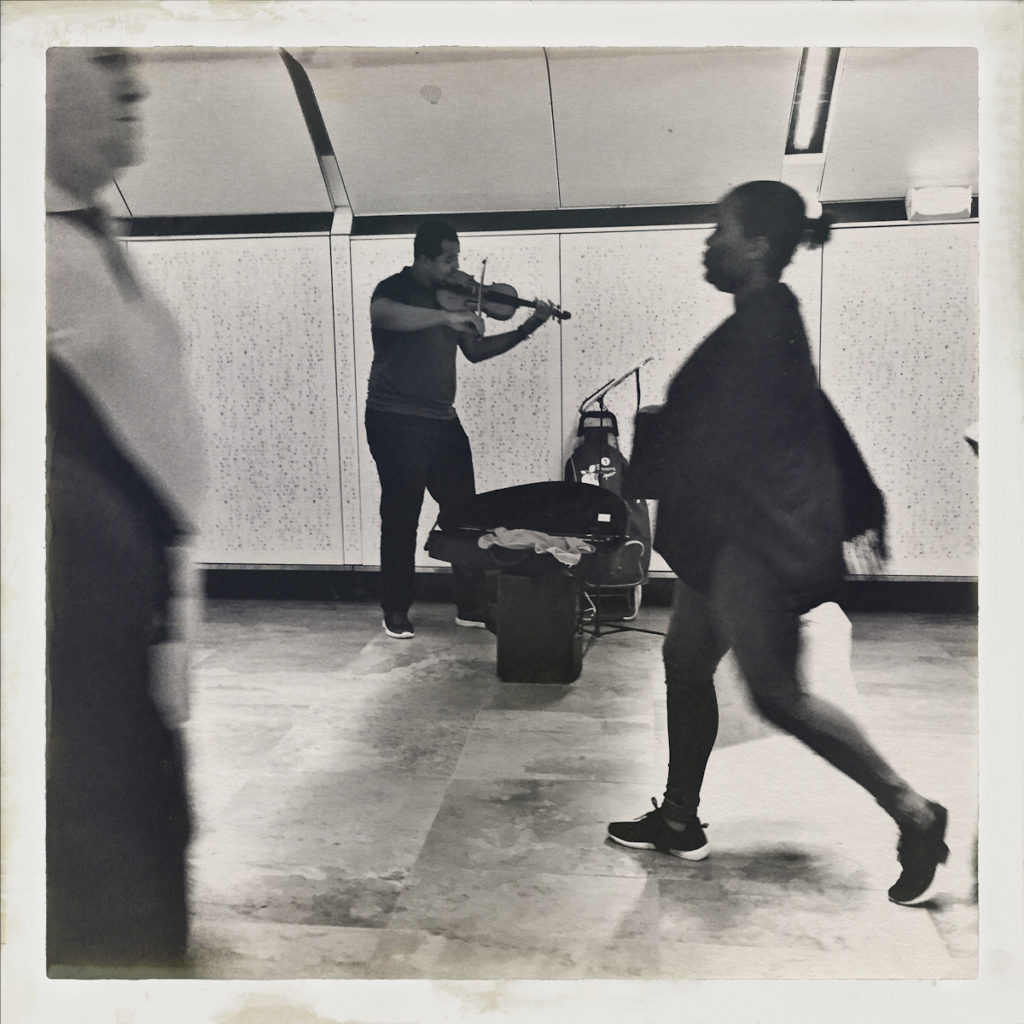

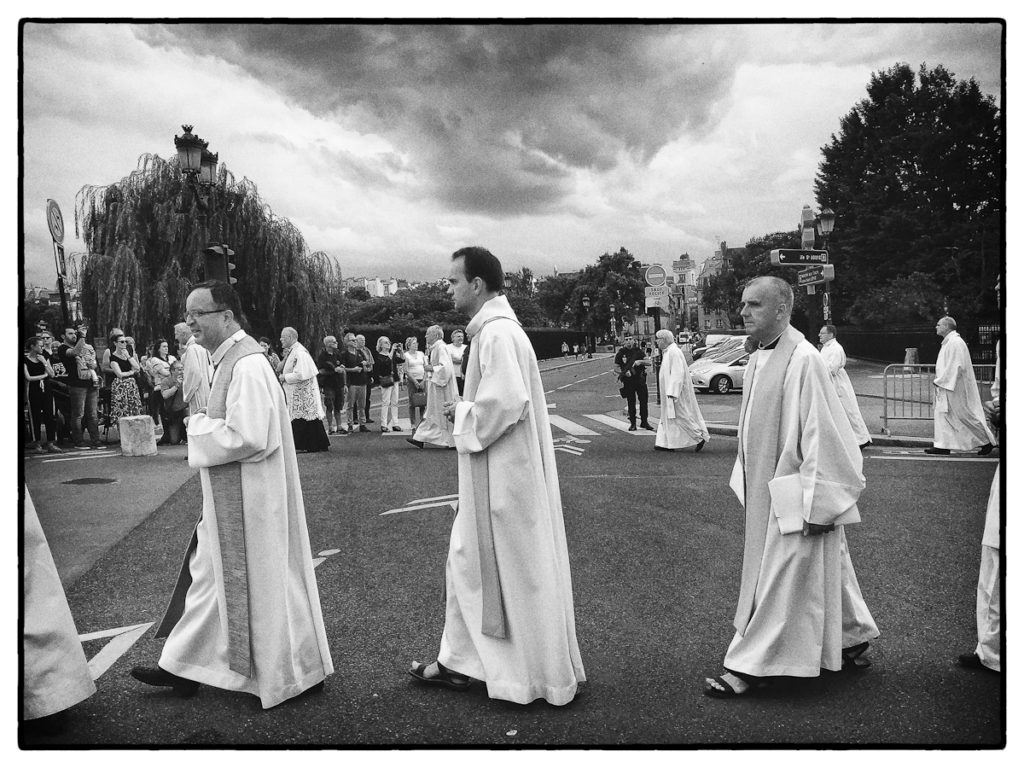

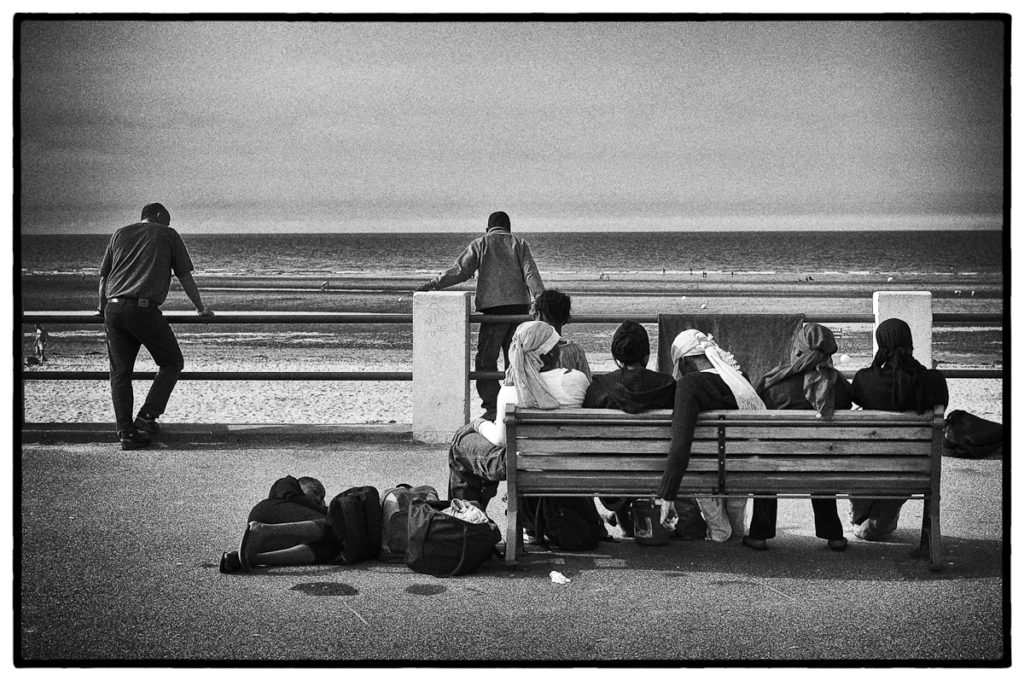

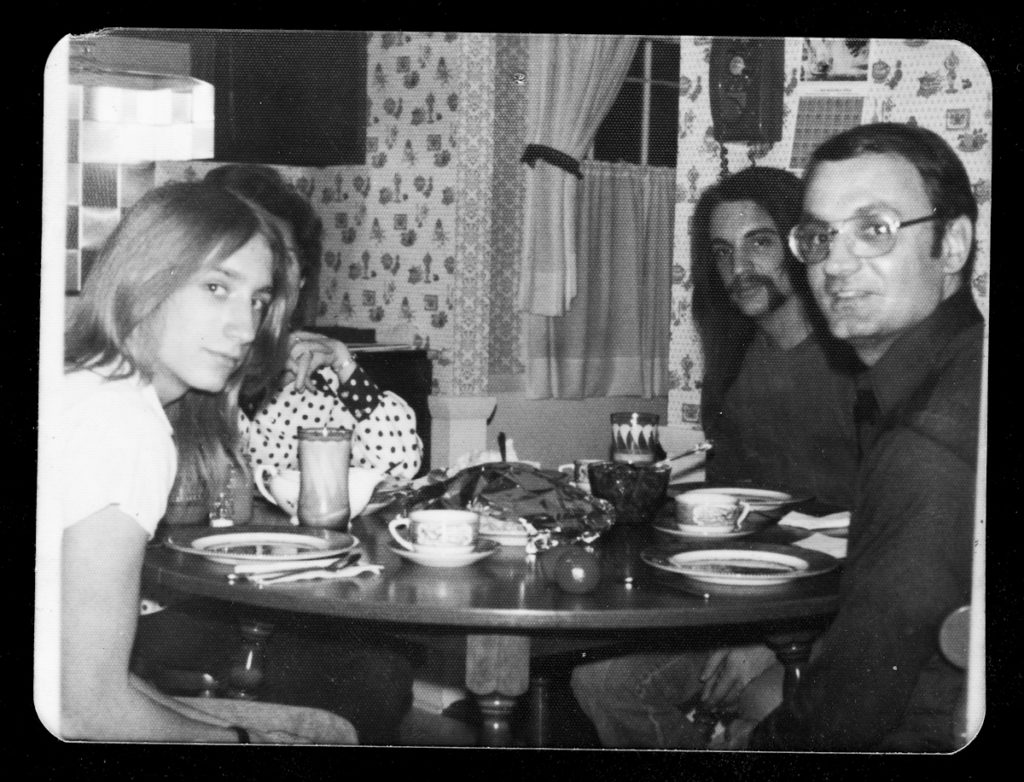

A Photograph Taken with a Film Camera. These People Exist