Bryan Appleyard, From INTELLIGENT LIFE magazine, March/April 2014

Kodak’s Tri-X is the film the great photographers love. When Kodak started collapsing—finally filing for bankruptcy in January 2012—some of the greatest photographers in the world panicked. Don McCullin immediately ordered 150 rolls of Kodak’s Tri-X black-and-white film. “I rang up my stockist and asked for them right away. I thought it was the end of my life. I don’t even know if they are still making it.”

Relax, Don, they are. After the company emerged from bankruptcy, a new company, Kodak Alaris, took over film production and, so far, it seems committed to producing Tri-X. But don’t relax too much. You are going to have to shoot those rolls pretty soon. Films, unlike digital sensors, have to be cared for. They need to be stored in fridges and even then, like supermarket food, they have expiry dates. This did not deter Anton Corbijn, the photographer and film-maker, from panic buying on a far larger scale than McCullin.

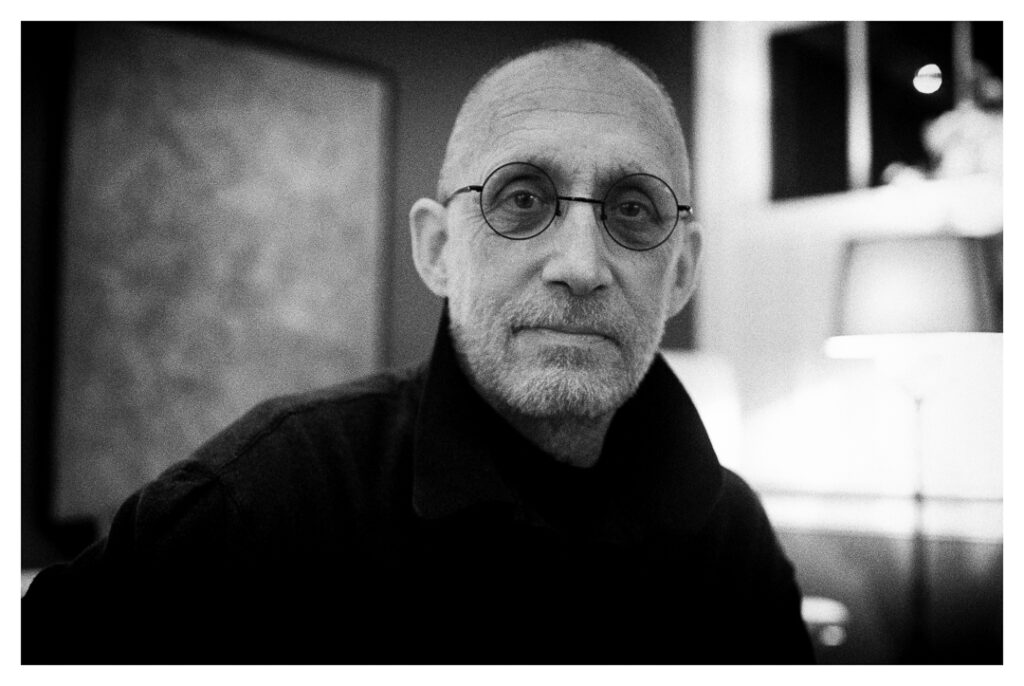

“I bought 2,500 rolls. My studio in Holland has three floors and there’s a fridge on each floor, all full of Tri-X. They must all be near their expiry date now. I don’t know what to do.”

McCullin shoots Tri-X alongside digital. Corbijn shoots almost nothing but film, Tri-X for black-and-white and Kodak Portra for colour. They are veterans—McCullin is 78 and Corbijn 58—but they are not Luddites and they are not wallowing in nostalgia. They are intent on preserving an artefact, a practice and an art form that, they say, simply cannot be matched by the technologies of digital photography. They are also keeping alive a cultural moment defined by one brand of film.

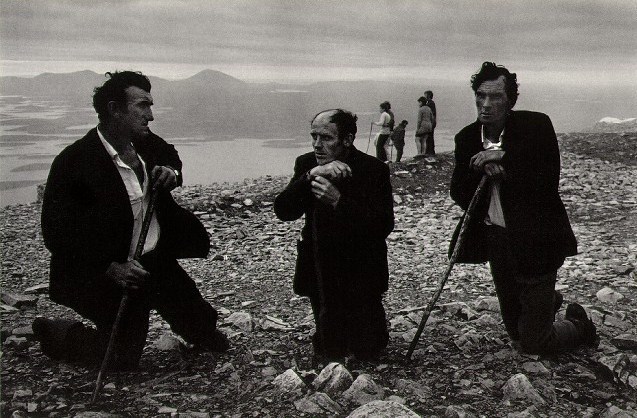

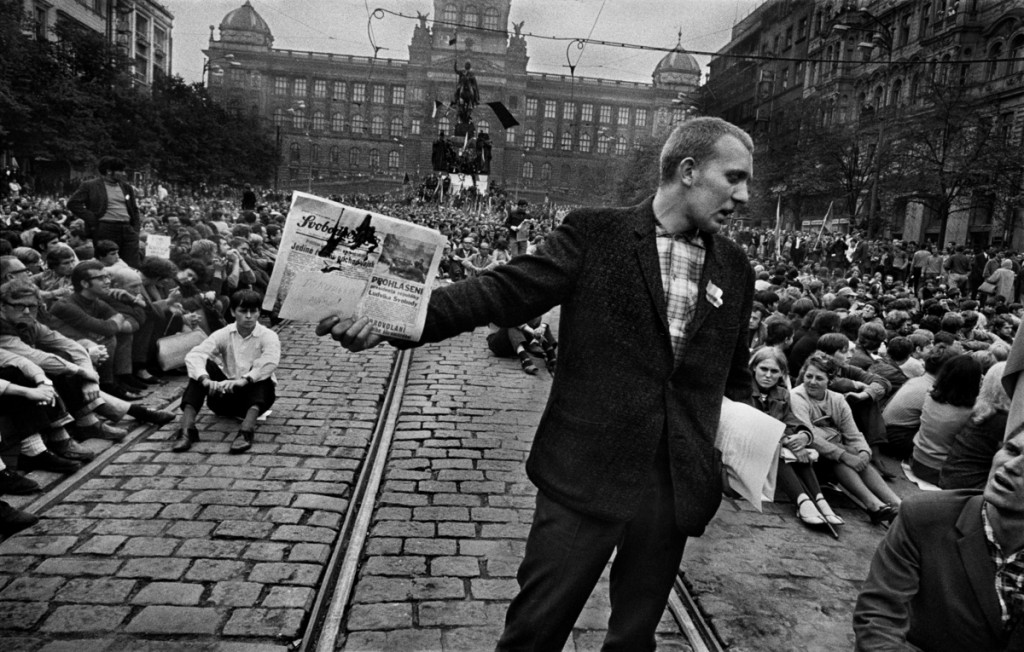

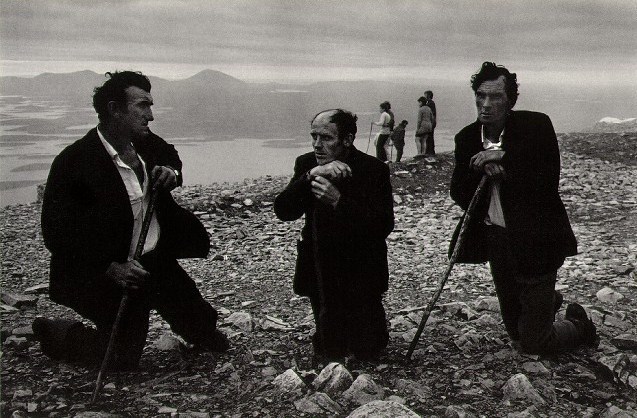

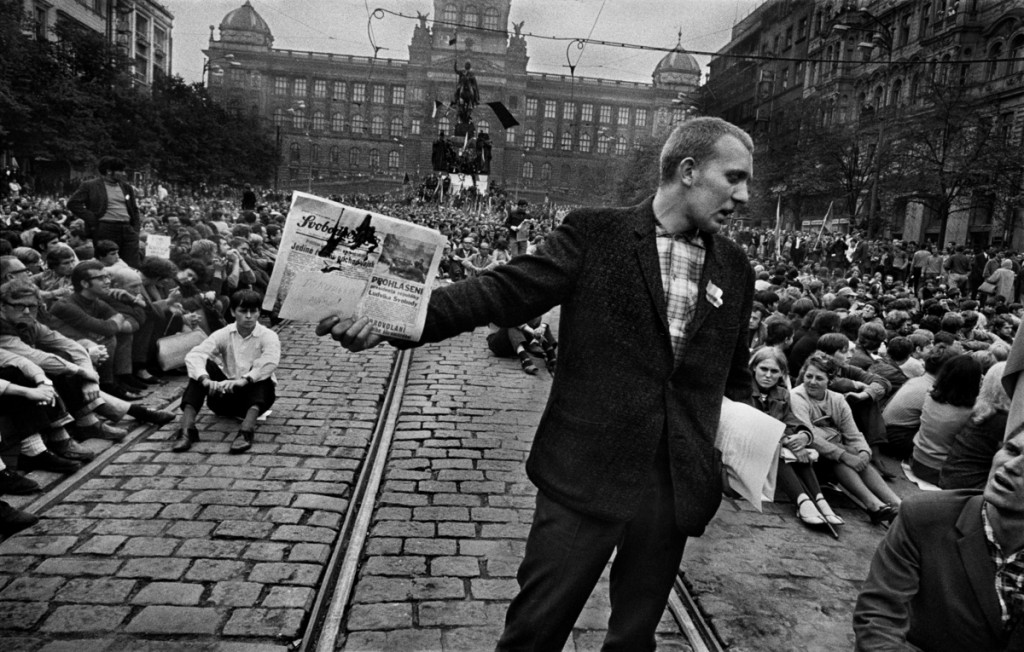

It was on Tri-X that McCullin captured some of the most powerful images of the Vietnam war: the shell-shocked American soldier with the thousand-yard stare and the fallen Vietamese soldier with bullets and family snaps scattered about him. It was on Tri-X that Corbijn took some of the greatest rock’n’roll photographs, including his documentation of the capering genius of Tom Waits, which has now run for nearly 40 years. In fact, if we include just a few other Tri-X users—Henri Cartier-Bresson, Garry Winogrand, Alfred Eisenstaedt, Irving Penn, Richard Avedon, Josef Koudelka and most of the finest of the photographers who worked for the Magnum agency—it becomes clear that this film may be the most aesthetically important technology in photographic history. The story of Tri-X is unique. It goes to the heart of how we see and what we see and what we may be losing as billions of casual, digital snaps are taken daily and as photographic integrity is subverted by the dead, flawless, retouched faces of actors and models that gaze blankly out at us.

As a commercial product, Tri-X is 60 this year. It first appeared in 1940, but only as a sheet film for large-format cameras. In 1954 it was released as a roll film for 35mm and medium-format cameras. In effect, it launched the golden age of black-and-white photography that was to last until the 1980s, as well as a new, urgent style of newspaper and magazine photography. It did so, first, through a simple technological innovation. Films are rated by their sensitivity, measured by what used to be called an ASA number, now known as ISO. The higher the number, the more sensitive (“faster” in photo-jargon) the film—or sensor—is to light, though the cost of high sensitivity may be an increase in grain or “noise” in the image. Tri-X was rated at 400 ASA, very fast for its time (modern digital cameras can go up to 26,000 or more). But it was also flexible and forgiving. Even if your exposure was slightly wrong, you could still get a decent shot and Tri-X could easily be manipulated in the darkroom—it became common chemically to push its ISO up to 800 or 1,600. Faster, more flexible film meant that professionals could now use the same film for outdoor and indoor shots and amateurs could be reasonably sure that their pictures would come out.

“I was technically awful when I started out,” says Sheila Rock, a photographer who made her name with shots of London punks in the 1970s. “I used to wonder if my images would come out, but with Tri-X they did.”

“Tri-X allowed me to make mistakes, of which there were many over the years,” Corbijn says, “and I somehow always got a print out of it.”

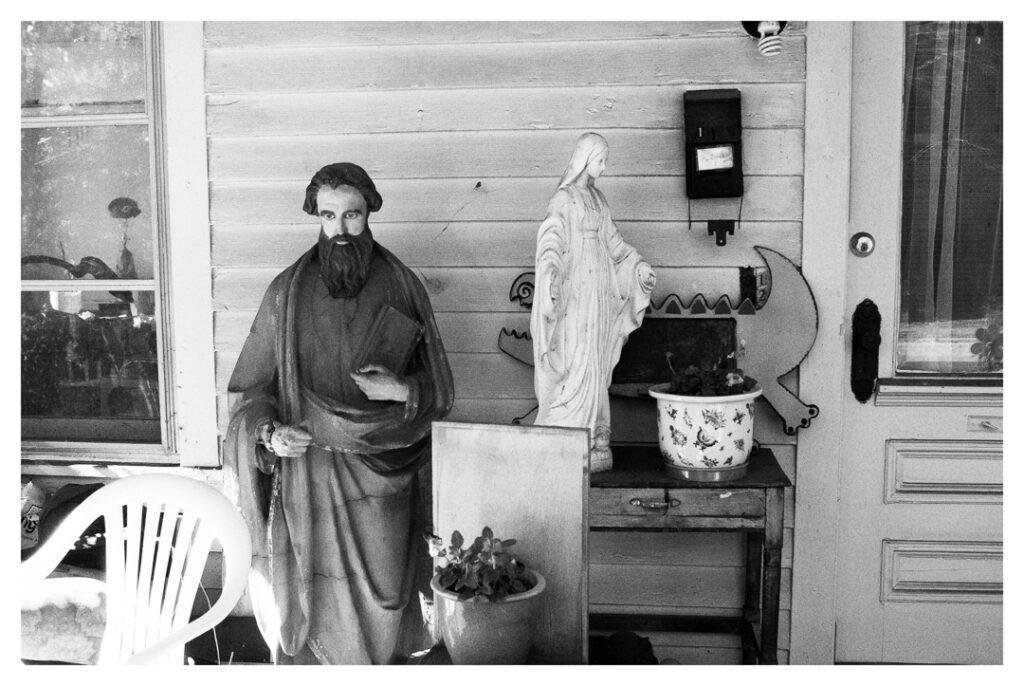

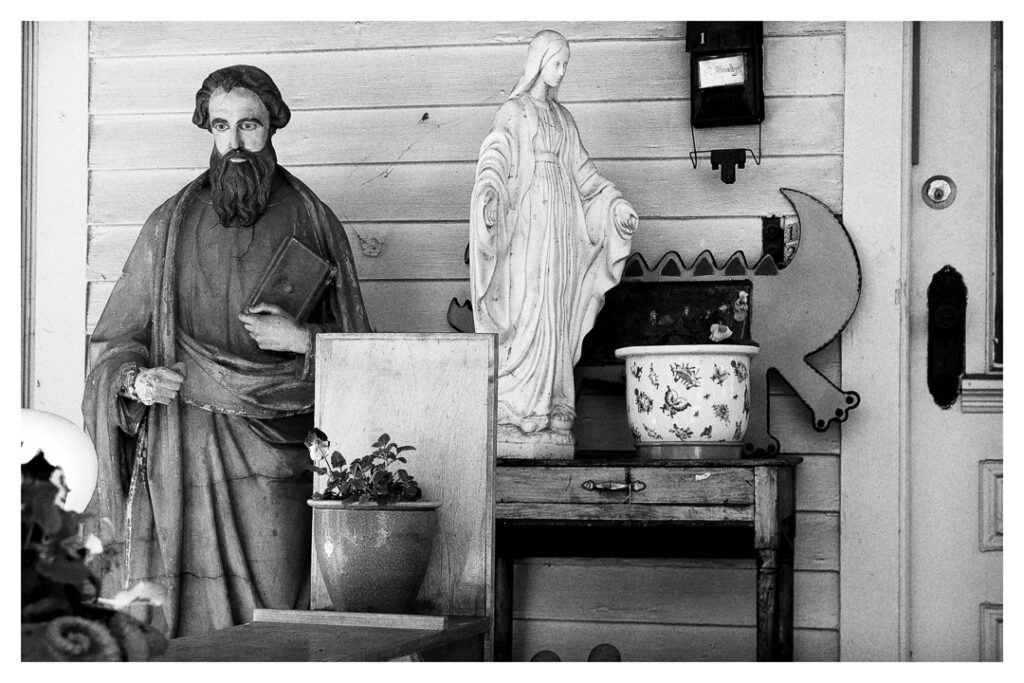

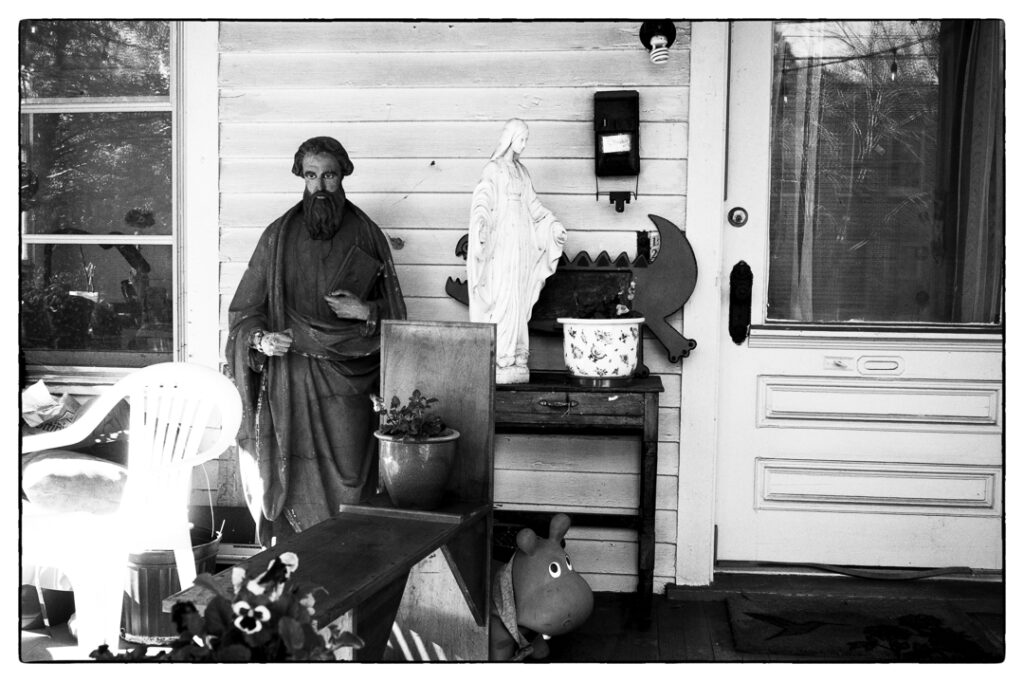

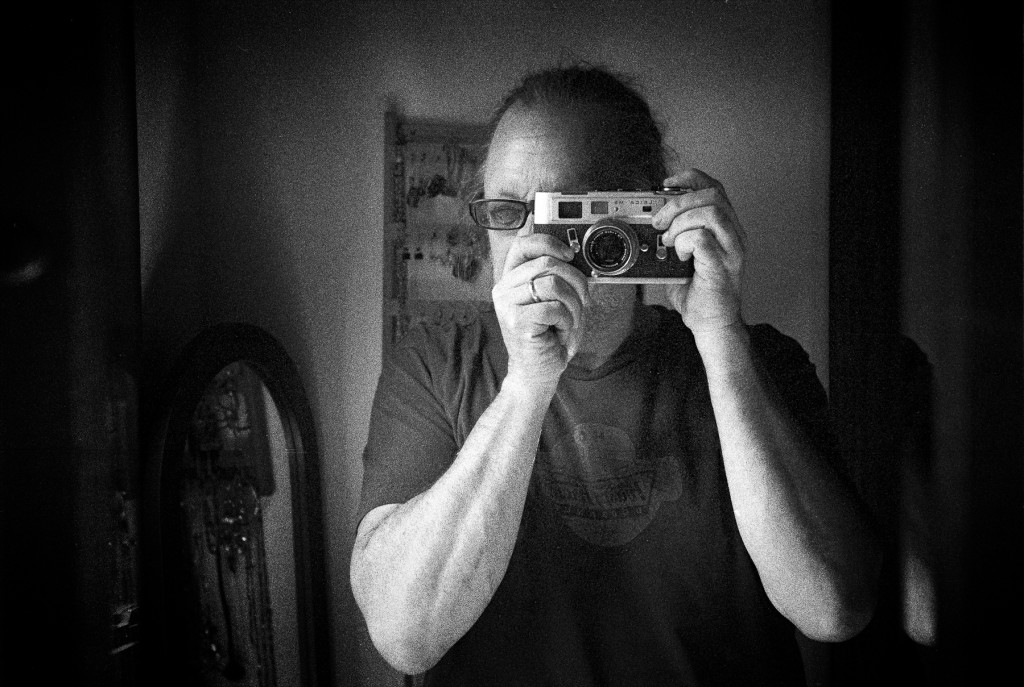

The more important innovation, however, was aesthetic. It is hard to describe exactly the look of a Tri-X picture. Words like “grainy” and “contrasty” capture something of the effect, but there is more, something to do with the obsidian blacks produced by the film and with a certain unique drama that made the rock photography of the Sixties and Seventies so powerful and distinctive. Steve Schofield, a British photographer, now in Los Angeles, who first encountered Tri-X in the Seventies, has a different word: “I got these incredibly contrasty negatives that still somehow managed to render detail in both the shadows and highlights. It’s got that steely look, not warm like lots of other film bases. It’s that basic look from Tri-X that I’ve tried to incorporate into my work which is now mostly shot digitally and is now colour…that monochromatic palette, but interpreting it with a simple colour base. If I do ever need to shoot black-and-white, I always prefer film and always opt for Tri-X.”

Another good word is “dirty”. In the early 1950s, monochrome photography was still dominated by the pearly perfection that came in with the black-and-white films of the Thirties. Those pictures had a wide tonal range—many shades of grey—but they tended to look flat. Tri-X, with its narrower tonal range, seldom looked flat and its harder, steelier style fitted the mood first of the realism of the Fifties, then of the casual, go anywhere, do anything mood of the Sixties. This dirtiness—a product both of Tri-X’s grain and its ability to work in low light—was the photographic correlative of three movements in other art forms: the Angry Young Men in literature, the School of London in painting, and the socially engaged work of Lindsay Anderson and Tony Richardson in the cinema. It was an aspect of an age that rejected the cosy, the safe and the merely glamorous in favour of the dynamic, the unstable and the pungent smell of lived life. From this emerged, in the Seventies, Anton Corbijn, perhaps the supreme artist of dirty Tri-X. In his early work, the dirtiness was intensified in the processing and the result was stark, imperfect shots with very visible grain that felt more realistic than any perfectly developed and processed shot.

“Grain is life,” Corbijn says, “there’s all this striving for perfection with digital stuff. Striving is fine, but getting there is not great. I want a sense of the human and that is what breathes life into a picture. For me, imperfection is perfection.”

The urgency of its images made Tri-X the first choice of reportage photographers, from great artists like Cartier-Bresson and McCullin down to the snappers on the local paper. All you needed was a Nikon F camera—expensive but tough and absurdly easy to use compared with today’s professional cameras—and a few rolls of Tri-X and, maybe, a darkroom in your bathroom, and suddenly you could call yourself a photographer.

It should be said that there may have been some magical thinking in all this. Tri-X produced brand loyalty that produced superstitious devotion. Though it was the first fast black-and-white film, it was not on its own for long. Ilford produced a competing 400 ISO film that many regarded as interchangeable with Tri-X and, in any case, long before Photoshop came along, the great darkroom craftsmen could do almost anything with printing and processing. “We could always do what you wanted in the darkroom,” says Mike Spry, a printer at the firm Downtown Darkroom who handled the films of David Bailey, Patrick Lichfield and Anthony Armstrong-Jones (Snowdon). “The great thing about black-and-white as opposed to colour was that you could change things around.”

Though it is true to say that professional digital photography of the face has converged on the dead, waxy, heavily retouched style that dominates the glossy magazines, it should also be remembered that good old-fashioned darkroom technique also involved extensive retouching. The finished product was different but no less manipulated.

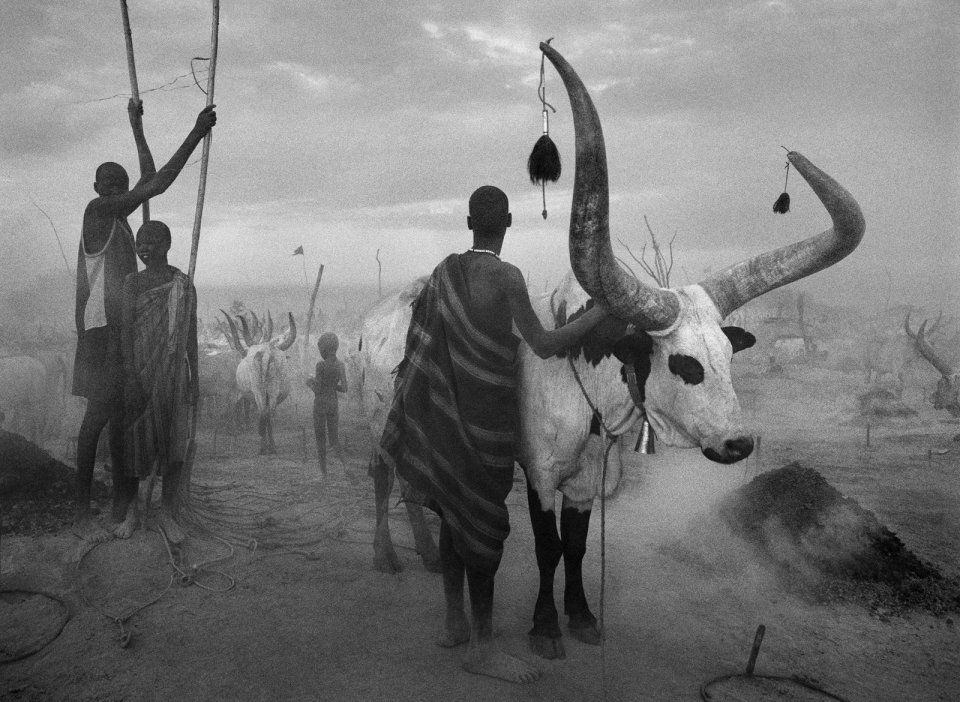

Nevertheless, it was Tri-X that created the possibility and then the demand for urgency, contrast, grain and drama in photography. It revitalised photography as a whole, but black-and-white photography in particular. In doing so it drew attention to the fact that, in spite of the incursion of colour and all the billions of hues and shades of digital, there remains something natural and true about the monochrome photograph, something that springs directly from the camera itself. Sebastião Salgado refuses to consider colour—he regards it as an offensive distraction—and has had his Canon digital cameras adapted so that the screen on the back shows only black-and-white.

It was also thanks to Tri-X that the wave of grainy, dirty reportage pictures changed high art photography. Art photography in the Sixties and Seventies, even in high fashion, was all about dirty grainy realism—and, of course, black-and-white.

“They were great times for printers like me,” Mike Spry says. “Just as hairdressing became an art form in those days, so did black-and-white photography.”

Corbijn’s doctrine that grain is life expresses a great truth about the Sixties and Seventies way of seeing the world. The age was defined by a rebellion against safe perfection and a quest for truth in experimentation, danger and dirt. Nothing captured this moment better than Michelangelo Antonioni’s extraordinary film “Blow-Up” (1966). A Bailey-like photographer called Thomas, played by David Hemmings, makes extreme blow-ups of some monochrome shots he has taken in a park and discovers, emerging ghost-like from the grain, a corpse. But the truth of this corpse—he returns to the park to check that it is really there—contrasts with the bright, high-resolution, high-colour, hallucinated and erotic fantasies of Swinging London. In the end, Thomas is seduced by the unreal. He turns away from the truth of the grain and embraces grainless hippie unreality, a choice symbolised by his willingness to retrieve a non-existent tennis ball. It is hard to imagine a more vivid statement of the legacy of Tri-X and of its centrality not just as a film but as an idea of the age.

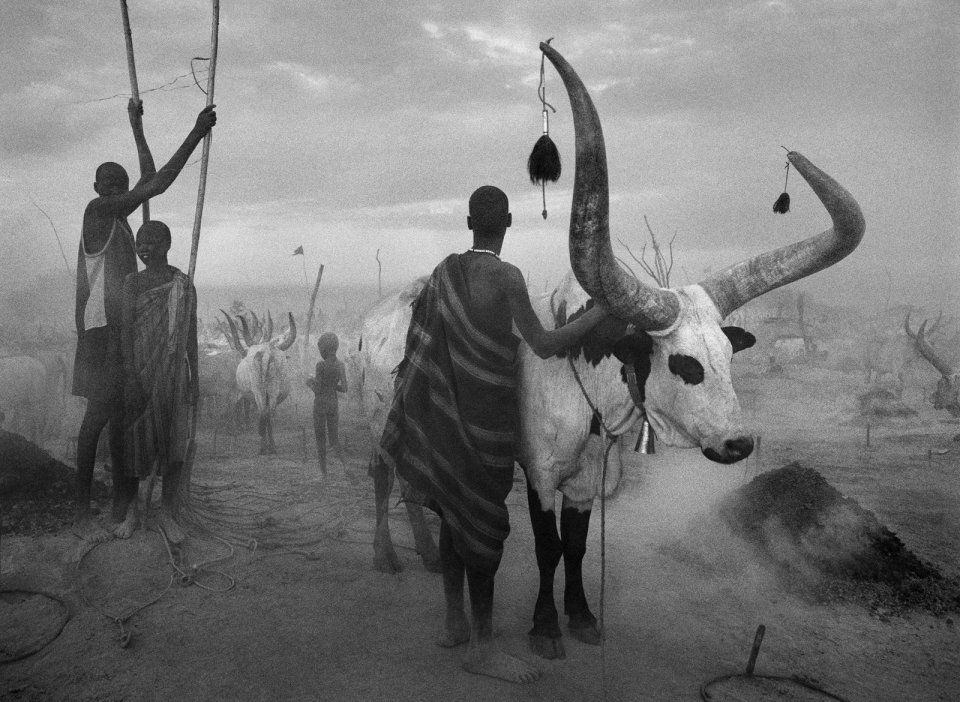

In the late 1990s Sebastião Salgado faced a crisis. Ever since the 1960s he had been shooting Tri-X, but he was not sure he could go on—either as a Tri-X user or even as a photographer. He specialises in long, heroic expeditions to produce his astounding pictures, most familiarly of the effects of industry on the third world. As airport security tightened, up to and after 9/11, he found it harder to persuade officials that his cases containing hundreds of rolls of film should be spared the X-ray machines. The signs say these machines do not affect film, but Salgado insists they do, especially if, like him, you pass through six or seven airports in a single trip. “The grain”, he says, “loses its structure.” The people at Kodak, meanwhile, have passed Tri-X through X-ray machines many times and they insist that it is not affected. Salgado, and many other pros, remain unconvinced.

His career and his next great work, “Genesis”, were saved by Canon. They claimed their latest digital cameras could match the quality of film and, after testing in the early 2000s, Salgado agreed. He now shoots everything on digital. Yet this is still a contentious point. Some say it is a simple matter of how many pixels can be packed on a sensor. Film photography, as an analogue form, produces pictures by allowing light to fall on chemically coated celluloid, creating an analogue of the scene in front of the lens. Digital, in contrast, collects light through a series of tiny sensors and then creates an electronic copy of the image. Film has very high resolution and early digital cameras with, say, 5 megapixels—5m sensor points—could not match this. This does not mean their photographs were less realistic, just that they could not be blown up beyond a certain native size without breaking down. For professionals, this makes cropping a digital photograph very costly in terms of available resolution, though software is available that interpolates additional pixels by working out what would be there if the resolution were much higher. Pixel counts have been rising steadily, and both Sony and Nikon now offer cameras for less than £2,000 that deliver 36 megapixels, a level of resolution that probably exceeds the capability of any 35mm film.

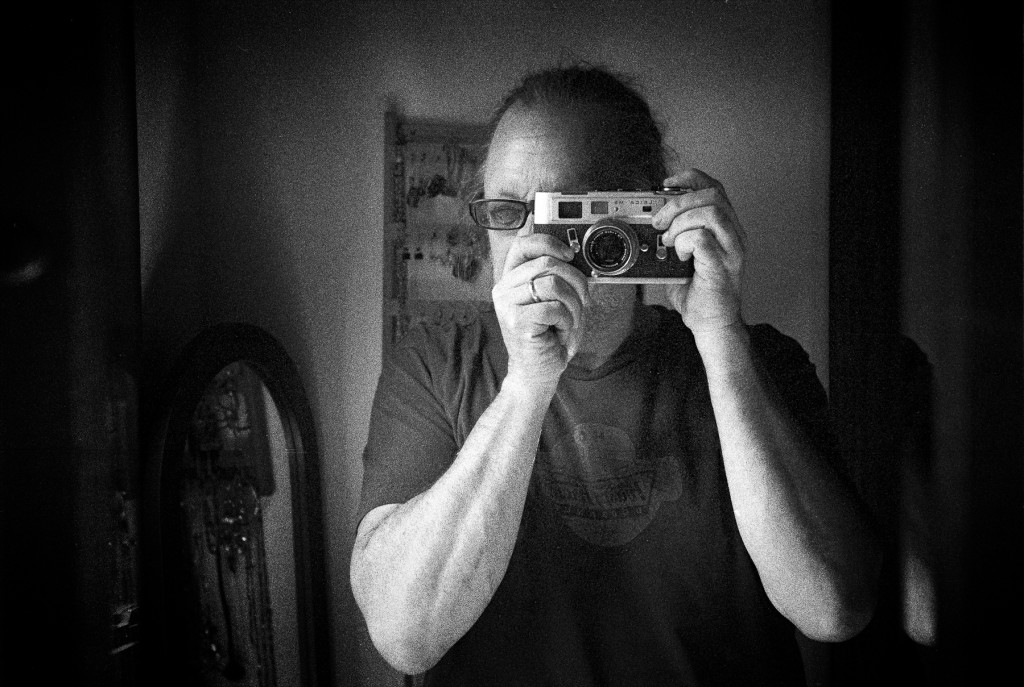

But, of course, it is not that simple. Squashing ever more pixels on to a sensor makes for technical problems and, in any case, it may not be the point. Film versus digital, McCullin points out, is still a debate among professionals and they are not talking about megapixels. Film is about more than just resolution, it is about authenticity. Film has other, more mysterious qualities.

“Film has more depth,” Sheila Rock says, “it’s the depth of going into a picture which I don’t find with digital. It’s much flatter. Some say it’s getting much better and I do see some things that have impressed me.”

Salgado knew this and he wasn’t quite prepared to go all the way to the digital look. He still wanted his all black-and-white pictures to look like Tri-X—and they do.

“I went to the exhibition of ‘Genesis’ at the Natural History Museum,” Rock says. “I looked really closely at the pictures and I thought they were Tri-X, but I was told they were digital prints.”

When I asked Salgado how this was done, he shrugged. He did not know: all he did know is that his technicians could produce the Tri-X look he liked. He never touches a computer and his post-production work is done by assistants at his studio in Paris. In fact, and this is a sign of the image-making times, many widely available digital photo-editing programmes now offer “film emulation”. You can simply scroll through a list and pick which type of film you want. Click on Tri-X and your picture will instantly be transformed—grain, drama, dirt and all. It works very—to devotees, alarmingly—well.

This software trickery, inserted into the digital algorithms to mimic an old manual craft, is another symptom of the now familiar phenomenon of analogue defiance, a rebellious hunger for the pre-digital world. Sales of vinyl records are now going up again, resistance to e-books can be fierce and, in New York, an art magazine called Master Cactus has emerged, which is only available on a tape cassette. In photography, the company Lomography has carved out an odd little niche market for plastic and toy film cameras whose dodgy construction produces bizarre and unpredictable effects. Polaroid cameras are on sale again and Fujifilm has produced its own version of instant snappery with the Fuji Instax film. Online, the 100m-plus users of Instagram can apply filters to give their pictures a variety of retro, filmish looks. People seem to be perversely drawn to the shortcomings of film photography—the light leaks of Lomography’s toy cameras, the strange starkness of small Polaroids and even, on Instagram, the corner-vignetting produced by vintage lenses.

Analogue defiance is a real and increasing force in the marketplace. It may be converting only a few to all the hassle and artistry of film, but, as a symbolic statement, it has had enormous impact on camera design. Film cameras, even the most expensive, were simplicity itself with only, in essence, three controls—focus, aperture and shutter speed. Professional or “prosumer” digital cameras have so many controls, it is impossible to list them all. And they are operated by a very user-unfriendly set of buttons. These were discouraging amateurs from trading up, so over the past few years manufacturers, led by Fuji with its X range, have been making retro-looking cameras with old-fashioned wheels and switches. This was so successful that even Nikon, one of the big makers of professional digital cameras, went so far as to produce the Df, a digital camera designed to look like the old Nikon F on which so much Tri-X was shot. It is an absurd and ungainly product costing over £2,700, which, by my reckoning, means you are paying at least £1,000 for the knurled metal knobs on top.

If that all represents a 180-degree turn away from digital perfection, some have gone even further, rejecting the perfect via a kind of 360-degree turn. Google Street View famously, notoriously, set out to photograph all the streets in the world using car-borne digital cameras. Two artists, Michael Wolf and Jon Rafman, decided to use selected images from the millions thus produced to create eerie works of art. These were technically poor photographs, but evocative nonetheless. It was, in its way, an attempt to resurrect the art of street photography, an art taken to a very high level with Tri-X in the hands of photographers like Winogrand and Cartier-Bresson. In their day, street photography was welcomed and safe; now it is dangerous—you can get accused of paedophilia, suspected of being some kind of snooper or, by police, of being a potential terrorist. Even worse, some of your subjects will know all about image rights and release contracts. Street View seemed to solve the problem.

But it was nothing to do with film and most of the analoguesque software gizmos are strictly for amateurs. So the question now becomes: if it can be done digitally right up to the standards required by Salgado, is there any point to Tri-X? Is there any point to film?

There is an old slogan among reportage photographers: “F8 and be there”. F8 is usually the optimum aperture on the lens, the setting that gives the best performance and is most likely to get the shot. “Be there” is just about the absolute necessity of your physical presence at the action. It is the necessity that overrides and underpins all others, so when, in 1948, Cartier-Bresson rushed to take a picture of Nehru announcing the assassination of Gandhi, it did not matter that it was out of focus, ill-lit and streaked with lens flares; all that mattered was that Cartier-Bresson was there to pluck something, anything, from the chaos of events. And, of course, he plucked a masterpiece.

It is this existential truth of photography that professional film-users fear is being lost in the increasingly virtual digital world. “Film is honest,” says Sheila Rock, summarising the views of them all, “Tri-X is honest.” Dishonesty, in this context, can be seen on any newsstand. The business of digital retouching is dictated by the demands of the American star system. Rock, who is obliged to use digital for commercial work, was even told by one client in response to her tastefully retouched images that “American women like to be more perfect”. The result is a universal digital convergence on a style that makes the stars of the covers look like Stepford Wives, robotic and impersonal—they might all be Jennifer Aniston or they might not, it does not matter. Anton Corbijn recently got one of his Tri-X shots into a glossy, but not until they’d asked him if it could be done in colour. He explained that, with film, the shutter click is terminal, at least in this respect.

Corbijn is regarded with envy and awe by many of his peers, but he does not call himself a professional—“there is so much I don’t know”—and he believes in the power of limitation to increase your creativity. This is why he sticks to film: it does not have the vast flexibility of digital, a flexibility that detracts from the power of the moment when the shutter fires. He is passionate about the material process of making a photograph from film.

“When I started, I felt that I didn’t want a normal job in photography, I wanted that sense of adventure when you meet someone and take a picture. I felt that digital is more like a job. You look at the screen to see if you have it right, then you take another picture. When I come back from a trip, I don’t know what I have exactly. I have to get it developed, so I won’t know for a couple of days. I like the tension of not knowing exactly what you have.”

“There’s nothing like going to Vietnam,” says McCullin, echoing the thought, “when I had to sit on the film for six weeks with a mental memory of the images I took. I had to be patient and carry all that film back to England. It became more precious by the week. And then you went to the lab wondering whether what you had was as good as what you thought you had. The waiting and the torment gave an edge to the whole procedure. Now, with digital cameras, you are looking at the screen on the back after every shot. It becomes an instant thing like fast food, it takes something away from the original menu.”

On top of that thrilling anguish, there is the manual craft of the darkroom where either the photographer himself or his trusted technician would use a bewildering array of methods—“ducking and weaving with bits of wire and stuff,” McCullin says—to manoeuvre the image as close as possible to the one in the artist’s head.

All this is being lost as darkrooms close and companies stop producing one type of film after another. Of course, many things are gained, but the full cost of digitalization in many fields, not just photography, is yet to be accounted. Kodak say that film in general and Tri-X in particular is safe. Yet I felt a pang when I asked how they were going to celebrate the diamond jubilee of their greatest film, and they said they had “no definitive plans we can share as of today”.

Never mind, we can do it for them by remembering Tri-X’s black-and-white golden age and celebrating its continuation in the works of Salgado, Rock, Corbijn and, of course, McCullin, the old master. He was off to India when we spoke.

“An Indian dawn with Tri-X,” he said, “it’s like being in heaven.”

Happy birthday, Tri-X, and many more of them.