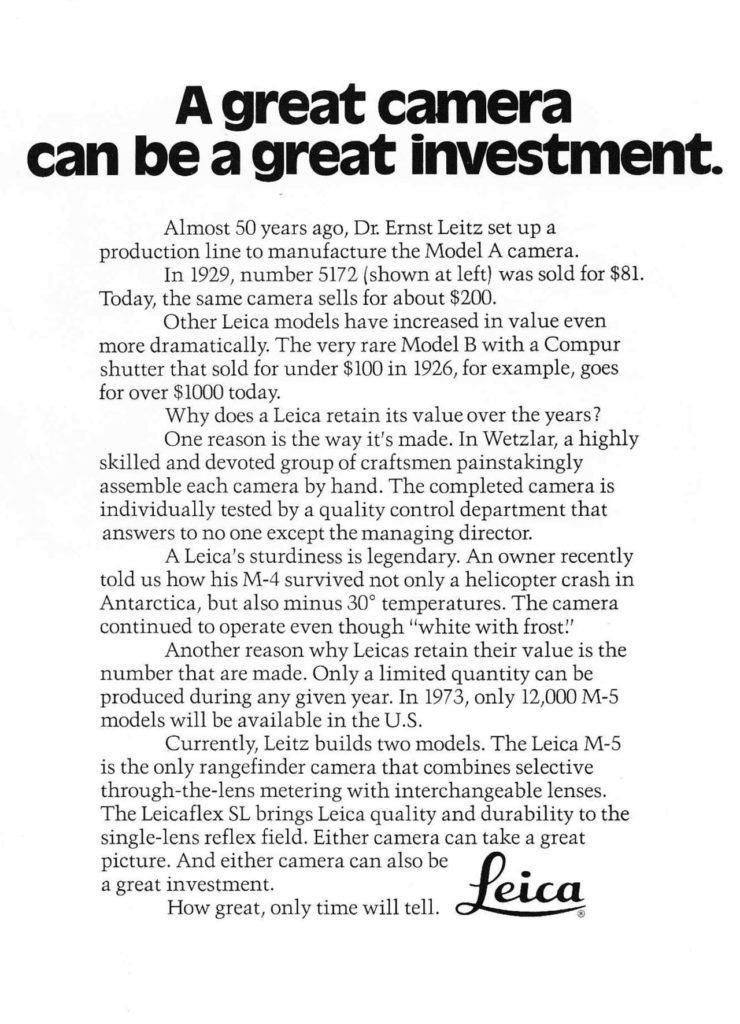

A Two Page 1973 Leica Advertisement

I ran across this 1973 ad for the Leica M5 and the Leicaflex SL and started thinking about the relative value of Leicas over time and how that value manifests itself today. Many of us consider our Leicas as ‘investments’ in the sense that it’s a pretty safe place to park some cash with the understanding that you’ll be able to get most, or all, or even more, out of it when you sell it. It’s a way I justify buying Leicas to my wife: we could either park an extra 3 grand in our bank account, serving no practical purpose except collecting chicken scratch for interest, or we could ‘invest’ it in the purchase of a Leica, a thing I’ll use and handle and admire and get some practical satisfaction from. I’ll take photos with it and it will inspire me to write about it on the blog. I’ll either like it or I won’t, but I’ll have the experience of having owned it, used it, better understood and appreciated it. And then, if we need the money again, I’ll sell it to a Leicaphilia reader and usually break even. Voila! Money put to good use. And a reader gets a decent deal on a decent camera that they know they can trust. What’s not to like? Of course, Leica could help me circumvent this process by sending me a camera or two to test, but I’m pretty sure that’s not going to happen. Who knows? Surprise me, Leica. I promise you an honest review.

The first thing that struck me was how expensive, in real terms, the M5 was in relation to the Leica models that had come before. If you run the purchase price numbers given by Leica through an inflation calculator, you’ll come up with the equivalent amount of circa 2021 dollars that purchase price represents. So, for example, buying a Leica Model II d in 1939 for $100 was the equivalent of paying $1900 for it in today’s dollar; a IIIg in 1958 for $163 would be the equivalent of paying $1467 for it today ( interestingly enough, the Professional Nikon, the Nikon SP, with a 50mm Nikkor f/1.4, sold in 1958 for today’s equivalent of $3,000); today an M3 would cost new $2373, the M4 $2320. Expensive, but not prohibitively so. The M5 body, were it sold today, would cost $3663. That’s a big increase in price over the iconic M3 and M4. With a decent Leitz 50mm Summilux (the lens it’s wearing in the Leica advert), it’d cost you >$6000 in today’s money. So, Leicas were pricey even back then. And the M5, now the unloved ugly duckling selling at a discount to the M2-M7, commanded a premium price over the iconic M2, M3 and M4.

************

It also gives us some sense of why the M5 might have ‘failed’ in the market [arguable, but that’s a discussion for another time], as opposed to its failure as an evolution of the M system [which it most certainly was not]. In addition to being technically deficient as a pro ‘system’ camera (based on the inherent drawbacks of a rangefinder) in relation to the Nikon F2 and Canon Ftn, it cost a fortune. To compare, a Nikon F2 Photomic with 50mm Nikkor 1.4, then the state-of-the-art, retailed for $600, although in actuality it sold out-the-door for maybe $500. The M5, you paid full price. Throw in $350 for a Summilux. In today’s money, that means buying a new Nikon F2 with 50mm 1.4 Nikkor in 1973 would set you back $3100, while an M5 with a 50mm 1.4 Summilux in 1973 would cost the equivalent of $6070 today. The M5 with lens was essentially double the price of the top shelf Pro Nikon with lens, which was then the professional’s system of choice.

*************

What do they go for today? You can sell the M5 and Summilux you bought in 1973 today, almost 50 years later, for +/- $3500. It’s probably going to need a going-over by one of the few techs who still work on the M5 – Sherri Krauter, DAG, one or two others, but that’s the buyer’s problem, not yours. Not a bad return for a camera you’ve used for 48 years. An M4 body, purchased in 1969 for $2300 will fetch you $1500-$1800; a single stroke M3 $1300-$1500; a Leica II d you paid $1900 for in 1939, today, you’ll you get +/- $300. Not exactly a prudent “investment” if you’re looking for a return on your money, but certainly excellent resale value of something you’ve used for half to three/quarters of a century. Like most things Leica, what appears crazy can in reality be quite prudent. Taking it all into consideration, buying a Leica is, moneywise, pretty much a smart idea.