In 1971, Leica introduced its successor to the M4, the Leica M5. In development since 1966, the M5 represented a tour de force of then current rangefinder technology – it was the first metered M camera and the first 35mm rangefinder to combine interchangeable lenses with a through the lens (“TTL”) metering system. Among its other design innovations, its viewfinder incorporated a coupled light meter and shutter speed data in the viewfinder itself, it relocated the ungainly rewind crank of the M4 to the left end of the base-plate, its shutter speed dial overhung the front of the camera so you could set shutter speed while keeping you eye to the viewfinder, and it located the carry-strap lugs both at the left end of the camera so that the camera would hang vertically rather than horizontally when worn. It was also the first M camera to use black chromium for the finish of its black versions (much more durable than the black enamel previously used).

It’s semi-spot meter utilized a 8mm diameter double cadmium sulfide resistor located on a carrier arm centered 8mm in front of the film plane. When pressing the shutter release, the carrier arm swung down parallel to the shutter curtain and hid in a recess below the shutter itself. It remains, to this day, the most accurate meter ever put into a Leica M film camera. The M5 viewfinder used the same 68.5 base length and .72 magnification as the M4 with the added feature of viewing the shutter speed and match needle metering.

So, why is the M5 commonly considered a “failure,” the camera that almost bankrupted Leica? Anecdotal testimonies claim that M5’s sat on dealers’ shelves for years after production stopped in 1974 after only 4 years. I purchased my first Leica, an M5, new in 1976, 2 years after its date of manufacture. I remember a steep discount to the official retail price.

The answer, I would claim, is not so much its aesthetics or its size (the two most common explanations for its demise) but rather a confluence of factors, both internal and external to Leica, a confluence that would have doomed the M5 in whatever guise Leica chose to go forward with its M series.

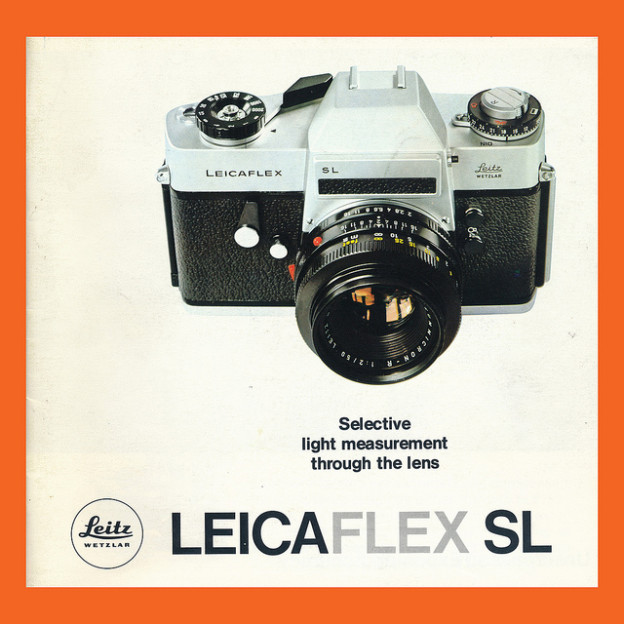

The first reason is simply the tenor of the times photographically. By 1971, rangefinder technology was seen by both professional and amateur as an antiquated throw-back with numerous disadvantages. Professionals had increasingly embraced the Nikon F system and its excellent but affordable optics, and amateurs had followed the lead and made SLR’s dominant in the 35mm market. Even Leica had bowed to the future, although reluctantly. At the beginning of the 1960s, Leitz continued to believe in the inherent advantages of the rangefinder over the SLR, but found it necessary for their continued relevance to produce and market their own SLR system, the Leicaflex.

The second reason, and I think the most apt, is Leica’s decision to produce the bargain priced Leica CL system in conjunction with the M5. Leica sold 65,000 CL’s between 1971 and 1974, mostly to the amateur market, at the same time it was marketing the M5 to professionals. As such, the CL cannibalized a large portion of the market the previously addressed solely by the M series. The production numbers point to this conclusion: Leitz sold approximately 57,000 rangefinder cameras in the initial 4.5 years of the M4’s production (1966-1971) and 92,000 rangefinder cameras in the 4 years of the M5’s production. The CL accounted for more than 2/3rds of those sales, driven mainly by a price 1/5th of the M5. The truth of the ex post facto justifications for the modest sales of the M5 (i.e. it didn’t look like a traditional M) is belied by the obvious fact that the CL didn’t look like the previous M’s either and yet it sold briskly.

It was only with the appearance of Japanese Leica collectors in the 1990’s that demand and prices for the M5 rose to levels of other M’s. Unfortunately, the M5 has continued to labor under the stigma be being a “failure.” If you’ve ever used an M5, you’ll know its a wonderful camera, the last of the true Wetzler M’s built without compromise. I even think its a beautiful camera, especially the chrome version. Whatever you think of its aesthetics, it certainly doesn’t deserve the lingering stigma attached to it.