In 2012, Leica introduced the M9 Monochrom, a dedicated monochrome (B&W) camera, the first digital black and white camera in 35mm format. According to Leica, the Monochrom “builds on the rich tradition of analog black and white photography and brings authentic monochrome photography into the digital era.” With a full native resolution of 18 megapixels, the Monochrom easily bested similar megapixel color sensors; unlike Bayer sensors, the Monchrom sensor records the true luminance value of each pixel, delivering a “true” black and white image straight from the sensor. In addition, users could apply characteristic analog toning effects like sepia, cold or selenium toning directly from the camera; just save the image as a JPEG and select the desired toning effect, “no need for post-processing.”

Of course, few Monochrom owners are going to shoot jpegs. Most are going to shoot RAW files and post-process, and to that end, Leica gave original owners a free copy of Silver Efex when they purchased the camera: ” Purchase includes a plug-in version of Nik Silver Efex Pro™ software, considered to be the most powerful tool for the creation of high-quality digital black and white images. For pictures that perfectly replicate the look of analog exposures, Siver Efex Pro™ offers selective control of tonal values and contrast and an extensive collection of profiles for the simulation of black and white film types, grain structures, and much more.”

Which leads me to note the contradiction. Invariably, Leica users champion the uncompromising standards of the optics, while often simultaneously dumbing down their files post-production to give the look of a vintage Summarit and Tri-X pushed to 1600 ISO. As noted above, Leica themselves seem to have fallen for the confusion as well. They’ve marketed the MM (Monochrom) as an unsurpassed tool to produce the subtle tonal gradations of the best B&W, but then bundle it with Silver Efex Pro software to encourage users to recreate the grainy, contrasty look of 35mm Tri-X.

*************

Clearly, Leica claimed and marketed the Monochrom, not merely as a black and white digital camera but as a digital camera that could accurately recreate the black and white film aesthetic. The distinction may be fine, but it’s a distinction just the same, and I think it gets to the heart of what I see as a misconception about the Monochrom’s actual output. Don’t get me wrong: the Monochrom delivers stunning black and white files, super clean past 800 ISO, beautifully subtle tones, file sharpness rivaling Bayer sensors with twice the resolution. It’s just that its files don’t look like film capture, and as I’ve noted in previous posts about my Digital Tri-X solution, it doesn’t particularly take to Silver Efex emulations, where a cheap D200 or a 4 mp Sigma SD15 Foveon best it for emulating the film look.

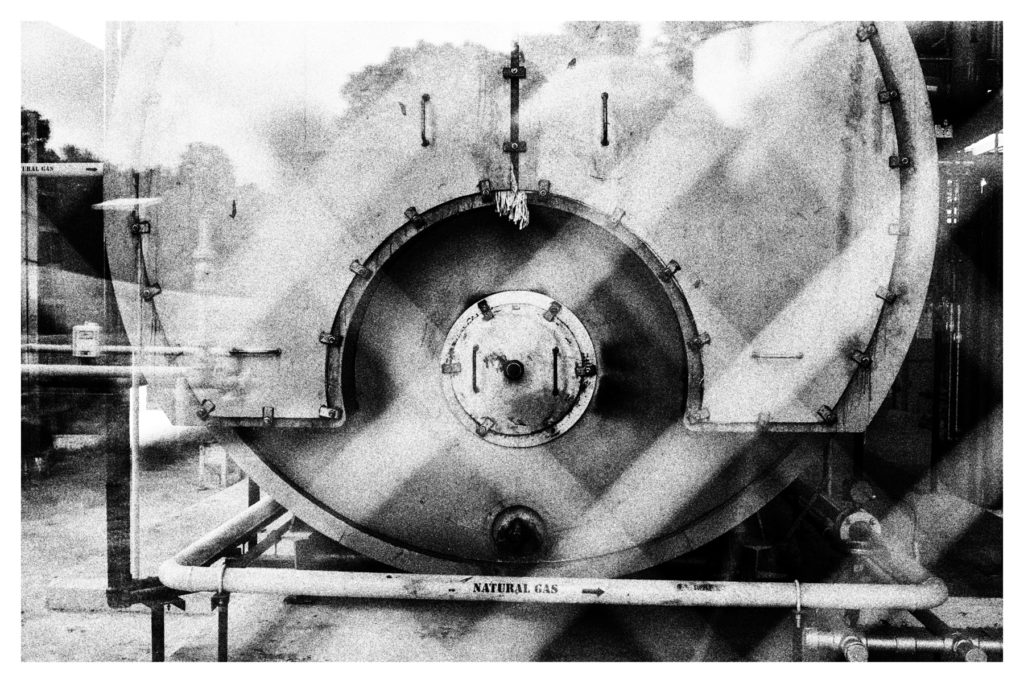

Here’s a Monochrom file processed in Lightroom without further film emulation:

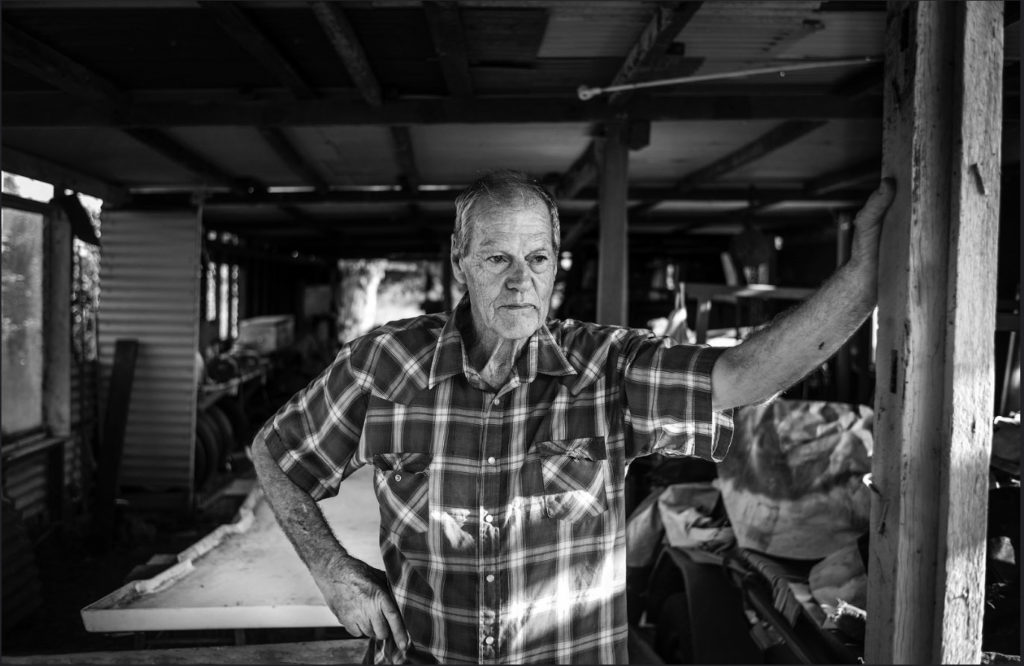

Here’s the same file run thru the Silver Efex Tri-X emulation:

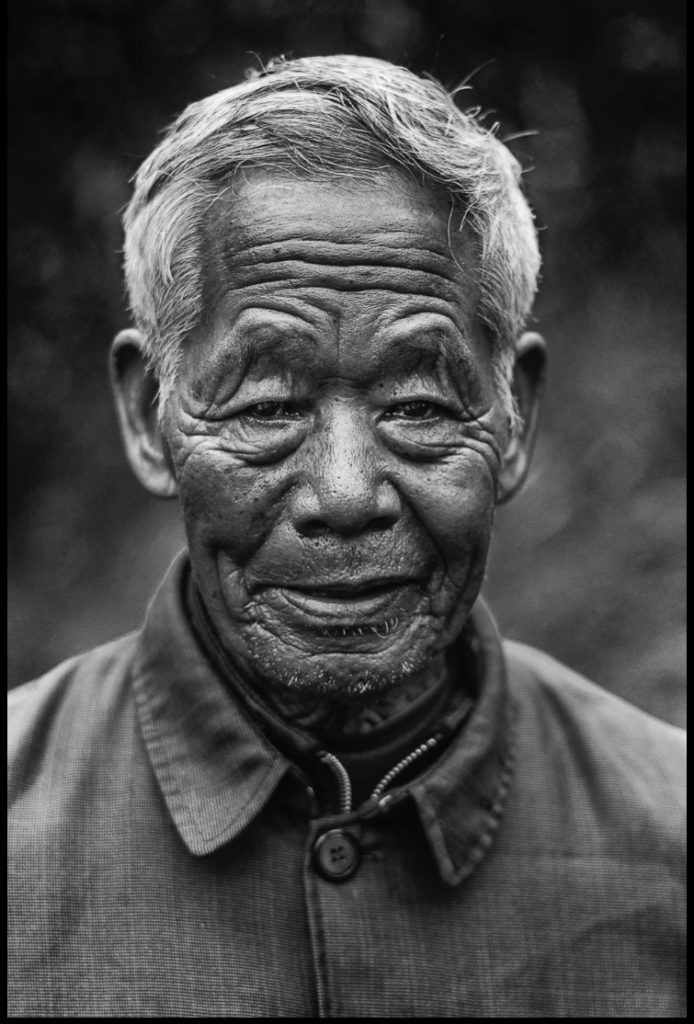

Here’s a Nikon D200 10 MP RAW file run through the Silver Efex Tri-X Emulation:

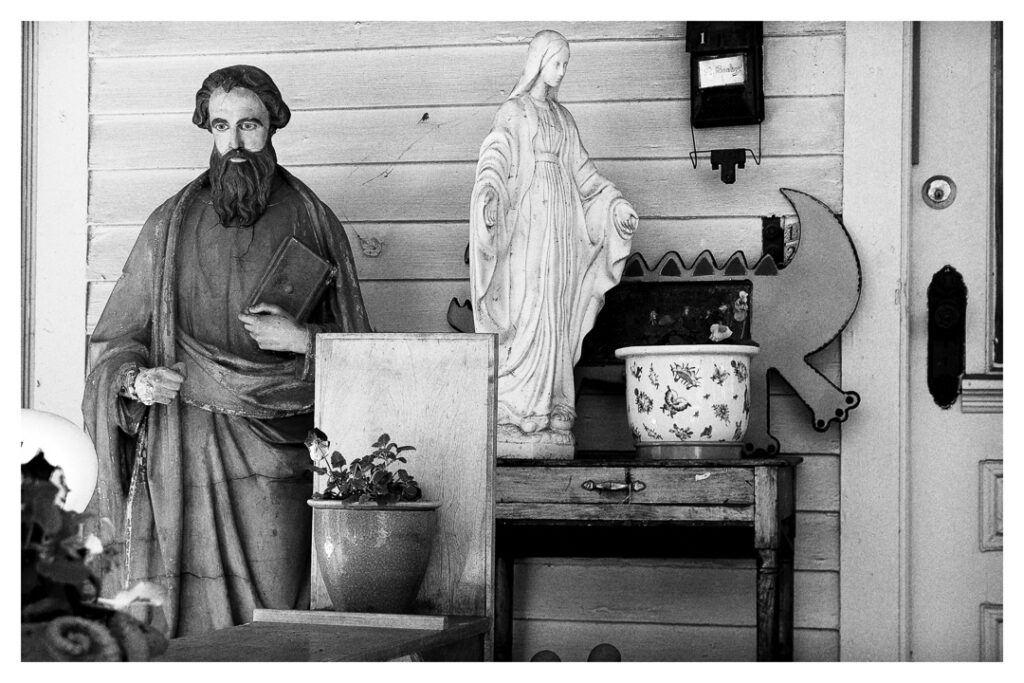

Finally, here’s a 14MP (actually 4.6mp when calculated in the Bayer manner) Sigma Foveon file from an SD15 run through the Silver Efex Tri-X emulation:

Now, acknowledging that aesthetic preferences are precisely that, preferences, my analysis is as follows: 1) The straight Monochrom file is nice for what it is – a digital B&W photo. It avoids that plastic look too often seen with digital B&W files and it has a nice graduated tonality. 2) The Tri-X Monochrom file is nice, but it doesn’t look like Tri-X. Too sharp, not enough grain structure evident. 3) The D200 and the Sigma Sd15 files are digital Tri-X, although the D200 benefits just a bit from less sharp optics; the Sigma file, even though <5mp, shows a sharpness and depth I doubt you’d get on a classic Tri-X shot with a 35mm Summicron. Sharper optics, sharp sensor.

*************

So, the question becomes, is the Monochrom worth it i.e. do we need a dedicated digital B&W sensor if our goal is, as per Leica ad copy ” to have a tool that combines state-of-the-art […] digital technologies to deliver black-and-white images of incomparable quality”? It certainly doesn’t hurt, but probably not. Don’t get me wrong: I love the idea of the Monchrom and its output can be stunning when done correctly. And it feels and performs like a Leica M, which is no mean feat. It’s definitely a fascinating camera and I applaud Leica for sticking their collective necks out and producing them.

But if you’re buying it to give you a leg up on recreating the B&W film look of your photographic youth, you may want to look at much more cost effective solutions I’ve noted elsewhere. It’s not something that you can’t also do with a regular Bayer sensored digital camera if you take your time. The key seems to be using a Bayer CCD sensor in the 10-12 MP range like that found in the Nikon D200 or the Fuji S3 Pro. Other alternatives are the DP1/2/3, SD14 or SD15 Foveons whose functional MP counts are somewhere around 10MP as well. It seems that 10MP is the sweet spot for both taking advantage of Silver Efexs’ simulated Tri-X grain structure and giving a resolution look similar to that you used to get with you M4, Summicron and Tri-X shot at box speed. A CCD sensor seems to help too.

You can put together a D200 with a AF 24mm Nikkor or older Nikkor Zoom of your choice for $200. An SD15 is going to run you $550 with a really fine Sigma optic like the 24mm EX DG. A twelve year old CCD Monchrom is going to run you $3500-$4000. Is it worth the price differential? That’s not a question to ask Leicaphiles, as, with Veblen Goods, you don’t buy on price but rather other intangibles. But, for all its cache, you don’t need a Monchrom if you aspire to, in Leica’s words, “to transform analog black and white into digital.” A ratty old D200 or Fuji S3 PRO will do just fine.