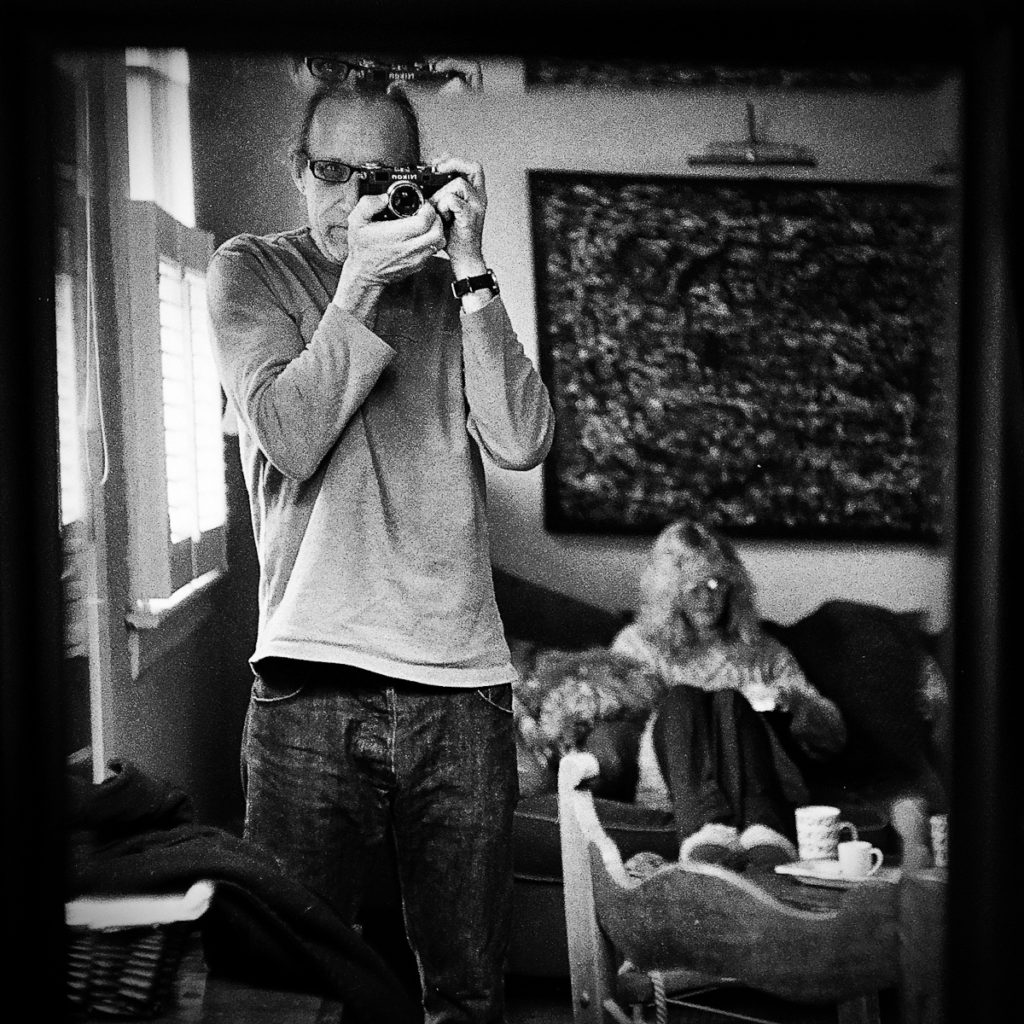

By Mark Twight. All photos by the author. You can see Mark’s work at www.marktwight.com

I was born in the mountains. I grew up middle class in an American city. I climbed mountains professionally for twenty years, making first ascents in the Americas, Europe and Asia. In those years I wrote articles for magazines, shot pictures to illustrate them and gave multi-media presentations in the U.S. and Europe. Later I wrote two books on the subject. Both won awards and were translated into German, Italian, Spanish, Slovenian, and Polish.

Mountain climbing and movie work allowed me to travel to incredible places I would not have otherwise seen. Antarctica. Bulgaria. Israel. Iceland. Japan. Tibet, Nepal and Pakistan. Norway. Argentina. Bolivia. Australia. France, Italy and Spain. Detroit. Alaska. China. Russia. Kazakhstan. Canada, of course. And all over the American West.

I have carried notebooks, a pen, open eyes and a camera in every place but I am not a photographer. I have a camera. I point it at things. I know my way around it, the darkroom and the computer. My attitude and the fact that I do the things I photograph gives me unique perspective. Although I am not now the man of action I was, what I did informs what I do. And what I will do in the future.

*************

I was anti-Leica for years. I thought it was snobbery. I shot an old Fujica HDS in the mountains because it was waterproof but eventually the fixed 38mm lens was too tight. I bought a Nikon FM2 with a 24mm even though it was enormous compared to my partner’s Rollei. Later I graduated to a Nikon F3, and a Angenieux 70-210mm zoom. I learned my way around the darkroom, developed and printed through many, many nights and eventually got back to Nikon optics and an F5. Despite the magnificent utility of the Nikon, my experience working in black and white introduced me to the Leica brand and the famous shooters who used it. I couldn’t afford to invest so I found adequate enough cons to outweigh the pros.

Then I did a job that paid enough to buy a M6 and 28mm lens. I compared it to my F5 with a 20-35mm f2.8 lens and once I saw the results I switched wholesale. In the mountains Leica lenses easily outmatched my best Nikon primes. The 28mm Elmarit held details when overexposed, captured astonishingly rich color, and separation. I loved pointing into the sun. I shot muddy cyclocross races, sand-boarding the dunes, and in the snow. I carried it in the Alaska Range and even when temperatures dipped to -30F, when plastic film canisters shattered, the camera functioned without problem. In 2001 I bought a Panasonic Lumix digital camera because it supposedly had a Leica lens, then a Canon S80 for its manual functions, then a G9, and later, a compact S100. As a reaction to muddy details at relatively low ISO values I bought a full-frame Nikon D800 so I could use my old 20-35mm but it was no pocket camera so a Sony RX1R with a fixed 35mm f2 Zeiss lens came next.

Instead of a darkroom I had Lightroom. The film in the refrigerator expired. I sold one M6 body. Eventually, I gave another to my friend because I knew he would use it. The beautiful Leica lenses sat idle. Regret nagged at me. I lived with it easily for years but it grew. And itched. I knew that sooner or later I would scratch. Then on a film set in 2014 Zack Snyder handed me his Leica Monochrom and said, “If anyone should have a camera that only shoots black and white, it’s you.” I laughed but he was right, the Gym Jones website had been exclusively black and white from its launch in 2005. That statement matched my vision and attitude. I didn’t want it to be easy to read so I floated white text on black. The viewer had to want it. I converted all images to black and white to remove the distorting influence that color can have. What remained was raw, and essential. When I finally bought a Monochrom – 13 years after I put the last roll of film through my M6 – it felt like coming home.

I pulled the lenses from their cases and relearned how to focus manually. My love for taking and making pictures returned and within a year I’d traded the RX1R for a Leica Q and carried it with me everywhere. I loved the fact that — shot at f1.7 — the images had remarkably shallow depth of field for a 28mm lens. The Q easily handles high ISO so even this night owl can make pictures, and the auto-focus is snappy. I can’t change my spots though so I still convert color images to black and white with Silver EFX in the digital darkroom. Black and white is still the way I see. Kiss or Kill.

*************

Spending so much time staring at images on a large monitor made me a pixel Nazi. On the screen, with the ability to ruthlessly zoom in to any aspect of a picture creates a very different relationship to the image than I have when I stand back and appreciate the totality of fine print. Dissecting local contrast at 4:1 can break the heart of any image.

This got me thinking about sharpness, which I revered when I started shooting a Leica M6. Because that’s what I thought I was seeing when I compared the M6 images to those from the F5. But maybe it wasn’t that the Leica images were sharper, instead their crisp luminosity made the wholly-adequate slides shot with the Nikon appear flat. The M6 images felt vibrant and alive, with details revealed from deep shadow, and texture preserved in areas of hotly overexposed snow. Peering through the loupe I could see greater density, or maybe depth but it wasn’t necessarily increased sharpness that caused that. Honestly, like describing taste, I have difficulty explaining why a Leica image looks different. I do know that — after almost 20 years of living with these images it isn’t as simple as cost influencing appearance. I mean, many times in the past thirty years I have spent far more and received demonstrably less.

That said I started feeling like many of my digital images were too sharp. Harsh, even. That I couldn’t appreciate them without some jpeg compression or the physical equivalent: standing at an appropriate distance. Apparently, anything above 18 megapixels is irrelevant because that’s the maximum our eyes can resolve (this is affected by viewing distance, eyesight quality, etc., and not gospel of course). Yet we chase ever-sharper resolution with 30, then 40mp and 50mp sensors. My eyes get tired first, then my brain.

Perhaps this is a question of perspective. I want to feel the emotional impact of the whole, to re-see what my eyes actually saw, to remember or re-experience how I felt when I initially witnessed the scene I “captured” with my camera. Instead, I crop, I dissect, I zoom, unintentionally stripping away emotion until only the technical remains. Or maybe 0s and 1s just lack soul. Subject, timing and composition are my antidote to binary reductionism but I am still and often dissatisfied with the outcome of the digital capture + edit equation.

*************

In October 2016 I serendipitously encountered Nicholas Dominic Talvola at Chris Sharma’s climbing gym in Barcelona. He shoots film with old Leica M2, M3 and M4 cameras. Properly. Astonishingly. We swapped Leica stories, handed each other our cameras, and he told me about an old 35mm lens that glows when it is shot at f1.4. He shared some images with me and I knew what I’d been missing. “Those lenses are hard to find, man. Not many of them were made and you have to get the one from Germany, not Canada and in X range of serial numbers … it should have a bit of purple cast to the reflection of light off the lens.” And the rabbit hole opened beneath my feet. “You’re going to love it on your Monochrom but you’ll die once you start shooting film again.”

I remember film. And I sometimes wonder if the problem with 0s and 1s is the immediacy. The all-important Insta. Frequency over Quality. And the metaphor of it. Who has any idea what to value or what has value when the only option on these platforms is to ignore or to like? 0 or 1. And no volume knob.

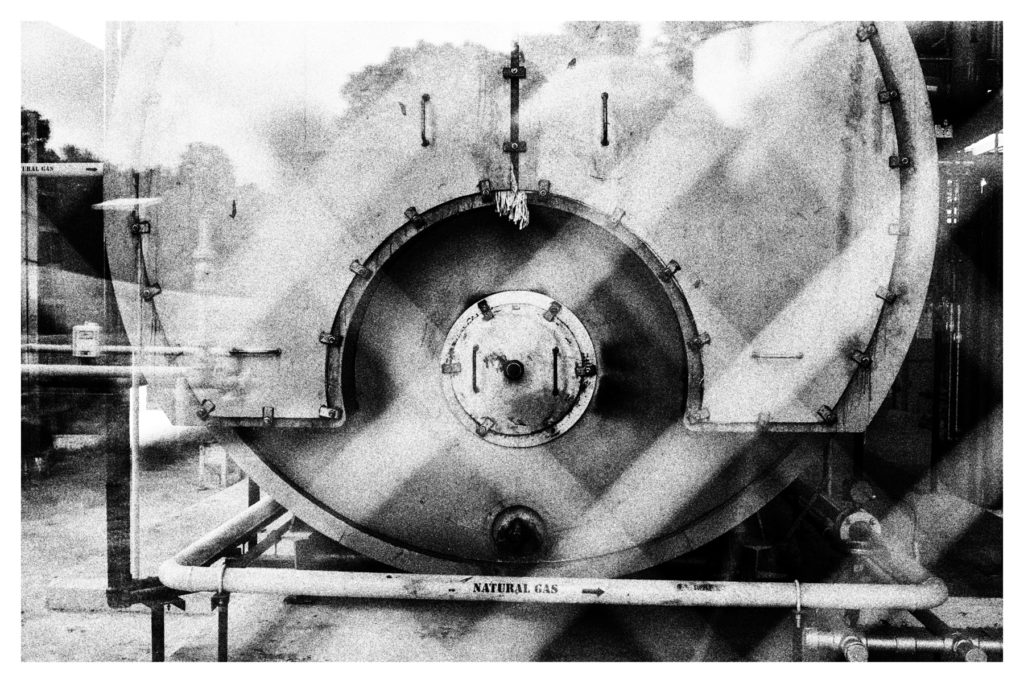

Instead, I try to make photographs that involve the viewer the way I was involved in the making. The Summilux 35mm lens Nicholas told me about gave my images an ethereal glow. It softens generally without sacrificing sharpness locally, luring the viewer to engage rather than evade.

When the image is too sharp and obvious its interpretive quality disappears. We accept what we see. And quickly move on. But when the focus isn’t obvious, when lines lead, when the whole implies more than it declares then we must interpret. The image – whether written or graphic – compels us to do so. It asks. We seek answers. Our own answers. And we wonder … which I always thought was the point.