Category Archives: Leica Photographers

Ralph Gibson Gets Old, Surrenders To Convenience

By Bruce Robbins, January 21, 2014. This article originally appeared under the title A Less Beautiful Ralph Gibson in www.theonlinedarkroom.com. Reprinted with permission of the author.

Ralph Gibson has gone over to the dark side, his beloved Leica MP and M6 film cameras replaced by a digital impostor that looks the same but eats pixels instead of silver. Who’da thunk it? He’s just published his latest book of photographs, Mono, all of which are digital. Ralph built his reputation on a certain look in his photographs, lots of contrast, empty black areas and sharp composition. He now believes he can achieve the same look with a digital Leica Mwhatever. Maybe he can but that’s hardly the point, is it?

Even one as ill-versed in Ralph’s work as I could quickly grasp that his photographs were organic, they had vitality and soul. More so than most other photographers’, his images lived and breathed. I saw that straight away when my pal Phil Rogers (who’s art school trained – rolls eyes) educated me about Ralph’s photography last year. It’s not everyone’s cup of tea and doubtless would give zone system aficionados conniptions but, love it or hate it, it was the antithesis of the perfect digital image. So I loved it.

Now, regardless of whatever direction Ralph’s future photography takes, we’ll all know that it’s not born of some deliberate combination of over-exposure and over-development – a technique arrived at over decades – but of some footering in Photoshop. No longer will it be unique. Now it’ll be just the same heavily manipulated pixel pap that I’m getting fed up of seeing on Flickr and other forums. (The Online Darkroom Flickr group is a rare exception. Check it out.)

Ralph, who was 75 last week, will now need to rewrite his personal website as well if he’s going to sell his new images there because he states, “All black and white prints are silver gelatin unless otherwise requested.” Somehow, I can’t see too many prospective buyers saying to Ralph, “No, it’s OK. I’ll pass on the hand-made, silver gelatin darkroom print. Just pop me out one of those nice, modern inkjet thingies.”

Some readers might think I’m going over the top but I don’t think I am. If you want an analogy between film and digital, I’d compare them to making a chair. Imagine if you were a craftsman who selected the seasoned wood, sketched out the design for the chair in a notebook, cut the timber to length, shaped it, carved the mortise and tenon joints, assembled it and finished it off with French polish.

Now imagine you had a computer on which you could design the chair. Imagine you could fire that design off to a CNC machine that carved the chair out of a block of wood and spat it out ready made and finished in varnish. The initial vision in both cases – the design – is the same. The latter would be the more perfect but which would you rather own?

Or here’s an analogy from the music world. You write the song, rehearse it with your favourite musicians and record it live. Or, you write the song, programme various computer-controlled synths to play the the various instruments absolutely flawlessly and record that. Which record would you rather listen to?

Why as a society are we so hell-bent on moving away from things made by human hand to soul-less computer-based crap? The lack of human input is so prevalent in the manufacturing process it’s palpable. I was a motoring writer for about 15 years and test drove hundreds of cars and I’d virtually no interest in any of them. They were the motoring equivalent of white goods.

Hand Built

The vehicles I like are mainly pre-1970s (although I had a soft spot for my MX5 because it was the Lotus Elan I couldn’t afford). If I won the lottery, after the DB5 and E-Type, I’d be paying visits to Morgan and Bristol and that’s it. In fact, when doing the motoring column, the only motoring magazines I actually bought on a regular basis were from the kit car industry – hand-built, you see?

Getting back to Ralph, I was aware he’d been “dabbling” with digital for years but, from what I’d read, he always seemed to be quite dismissive of it. Not in a bad way but he made it very clear that everything about his images screamed film and always would.

As far back as 2001, Leica were trying to tempt him with digital cameras without success. Listen to what Ralph said in an interview at that time, “Digital photography is about another kind of information. Digital photography seems to excel in all those areas that I’m not interested in.

“I’m interested in the alchemy of light on film and chemistry and silver. When I’m taking a photograph I imagine the light rays passing through my lens and penetrating the emulsion of my film. And when I’m developing my film I imagine the emulsion swelling and softening and the little particles of silver tarnishing.

“But anyway, the big emphasis in digital photography is how many more million pixels this new model has than the competitor’s model. It’s about resolution, resolution, resolution as though that were going to provide us with a picture that harboured more content, more emotional power.

“Well, in fact, it’s very good for a certain kind of graphic thing in colour but I don’t necessarily do that kind of photograph. So when it comes to digital, I have to say that digital just doesn’t look the way photography looks: it looks digital. However, I strongly suspect some kid is going to come along with a Photoshop filter called Tri X and you just load that and you’ve got yourself something that looks like photography (laughs).” My italics, Ralph’s laughter.

Photography or Digital

Now, everyone is obviously free to change their mind but I’m not sure there have been any developments in digital in the last few years that would negate anything Ralph said about his own view of photography or the materials he used. Did you see the way he spoke of “photography” and “digital” as two separate entities? Does that mean he’s no longer a photographer?

Why would a photographer who has built a considerable reputation using film ditch it in his 76th year? Is he getting too old to spend hour after hour in the darkroom or did Leica make him an offer he couldn’t refuse? Or was it the sudden realisation that all his earlier utterances about swelling, penetrating and softening (will that pass the censors? – ED) were wrong all along? Or was that just art speak designed to impress the pseuds?

Here’s Ralph’s (wholly unconvincing in my opinion) justification for taking the wrong fork in the road. Note that he concedes he’s now offering a less “beautiful” product.

“These words about making images could be written in English, French, or any number of languages we know exist in the world,” he said in promoting his book.

“I am writing both about images and my life long relationship to the creative process. We could talk about the moon in many different languages but it would still be the moon being described.

“So when I work in digital, I might be describing the same subject but in a different language, a somewhat altered syntax. But the subject is the same. And the very moment I discovered that I could get my “look” on digital, I was convinced that this was a new language that I wanted very much to explore.

“Imagine my excitement after 55 years in the darkroom. It must be said that the silver-gelatin print is still more beautiful than the ink-jet but at the rate technology is progressing it is not inconceivable that the substrates will become even more desirable. For the moment I am totally inspired and enjoy picking up my Leica and expressing my thoughts and visual ideas. I have always liked picking up my Leica…”

Sorry, Ralph, mate. You’ve just gone from designer label to store bought.

**********

Postscript: On February 1, 2014, Leica announced a limited edition Leica Monochrom “Ralph Gibson Edition, priced at 21,000 Euros (around $28,000). A total of 35 units were produced.

Gianni Berengo Gardin Talks About His Love of Film Leicas

Gianni Berengo Gardin is an Italian photographer who has worked for Le Figaro and Time Magazine. Considered a artistic heir to Henri Cartier-Bresson, like Bresson he has long used and admired Leica rangefinders. His work has been published in more than 200 photographic books and shown in the most prestigious galleries and museums around the world, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Now 82, Gardin boasts a personal archive of more than a million pictures.

Q. How long have you used a Leica? A. Always: although in the fifties I used a Rolleiflex 6×6 because the clients preferred medium format to the smaller, 35 mm film, but I always had a Leica III in my bag for my own use. Then in 1954, when Leica released the revolutionary model “M” bayonet, I was among the first in Italy to buy it in a shop in Venice, where I lived. I had to pay for it in installments because German quality has always been expensive here in Italy. Since then I’ve owned and used, in order, an M2, M4, M6 and M7, and I still continue to use my M7 as my primary camera, even today.

Q. It is still worth spending a significant amount on a simple Leica rangefinder when the market offers all kinds of models with all kinds of features at prices far more competitive? A. In the 50’s, the excellence of a Leica camera was clear. Today, the high level of optical and mechanical reliability remain, although the qualitative gap compared to other brands has narrowed. However, what remains important for me is the tradition of Leica. I feel a responsibility when I use my Leica, a responsibility to carry on the great photographic tradition of photographers from Dorothea Lange to Henri Cartier-Bresson, Eugene Smith, Josef Koudelka.

Q. You still prefer the film: Why? A. I trust its archival properties. I’m afraid that digital capture, without a physical medium, can not be sustainable over time.

Q. Have you tried a digital Leica? A. Yes I’ve used a digital Leica. The quality is excellent and it certainly gives you the advantage of flexibility and speed, but for my type of work its not so important to see the result immediately. It is said that older men are attracted to younger women: for photography, for me its the opposite. Instead of looking for the latest model I an romantically faithful to the classic models of the past. In my bag there will always be three film camera bodies and two wide-angles – a 35 mm and 28 – always allowing me to be close to my subjects.

The Tri-X Factor

Bryan Appleyard, From INTELLIGENT LIFE magazine, March/April 2014

Kodak’s Tri-X is the film the great photographers love. When Kodak started collapsing—finally filing for bankruptcy in January 2012—some of the greatest photographers in the world panicked. Don McCullin immediately ordered 150 rolls of Kodak’s Tri-X black-and-white film. “I rang up my stockist and asked for them right away. I thought it was the end of my life. I don’t even know if they are still making it.”

Relax, Don, they are. After the company emerged from bankruptcy, a new company, Kodak Alaris, took over film production and, so far, it seems committed to producing Tri-X. But don’t relax too much. You are going to have to shoot those rolls pretty soon. Films, unlike digital sensors, have to be cared for. They need to be stored in fridges and even then, like supermarket food, they have expiry dates. This did not deter Anton Corbijn, the photographer and film-maker, from panic buying on a far larger scale than McCullin.

“I bought 2,500 rolls. My studio in Holland has three floors and there’s a fridge on each floor, all full of Tri-X. They must all be near their expiry date now. I don’t know what to do.”

McCullin shoots Tri-X alongside digital. Corbijn shoots almost nothing but film, Tri-X for black-and-white and Kodak Portra for colour. They are veterans—McCullin is 78 and Corbijn 58—but they are not Luddites and they are not wallowing in nostalgia. They are intent on preserving an artefact, a practice and an art form that, they say, simply cannot be matched by the technologies of digital photography. They are also keeping alive a cultural moment defined by one brand of film.

It was on Tri-X that McCullin captured some of the most powerful images of the Vietnam war: the shell-shocked American soldier with the thousand-yard stare and the fallen Vietamese soldier with bullets and family snaps scattered about him. It was on Tri-X that Corbijn took some of the greatest rock’n’roll photographs, including his documentation of the capering genius of Tom Waits, which has now run for nearly 40 years. In fact, if we include just a few other Tri-X users—Henri Cartier-Bresson, Garry Winogrand, Alfred Eisenstaedt, Irving Penn, Richard Avedon, Josef Koudelka and most of the finest of the photographers who worked for the Magnum agency—it becomes clear that this film may be the most aesthetically important technology in photographic history. The story of Tri-X is unique. It goes to the heart of how we see and what we see and what we may be losing as billions of casual, digital snaps are taken daily and as photographic integrity is subverted by the dead, flawless, retouched faces of actors and models that gaze blankly out at us.

As a commercial product, Tri-X is 60 this year. It first appeared in 1940, but only as a sheet film for large-format cameras. In 1954 it was released as a roll film for 35mm and medium-format cameras. In effect, it launched the golden age of black-and-white photography that was to last until the 1980s, as well as a new, urgent style of newspaper and magazine photography. It did so, first, through a simple technological innovation. Films are rated by their sensitivity, measured by what used to be called an ASA number, now known as ISO. The higher the number, the more sensitive (“faster” in photo-jargon) the film—or sensor—is to light, though the cost of high sensitivity may be an increase in grain or “noise” in the image. Tri-X was rated at 400 ASA, very fast for its time (modern digital cameras can go up to 26,000 or more). But it was also flexible and forgiving. Even if your exposure was slightly wrong, you could still get a decent shot and Tri-X could easily be manipulated in the darkroom—it became common chemically to push its ISO up to 800 or 1,600. Faster, more flexible film meant that professionals could now use the same film for outdoor and indoor shots and amateurs could be reasonably sure that their pictures would come out.

“I was technically awful when I started out,” says Sheila Rock, a photographer who made her name with shots of London punks in the 1970s. “I used to wonder if my images would come out, but with Tri-X they did.”

“Tri-X allowed me to make mistakes, of which there were many over the years,” Corbijn says, “and I somehow always got a print out of it.”

The more important innovation, however, was aesthetic. It is hard to describe exactly the look of a Tri-X picture. Words like “grainy” and “contrasty” capture something of the effect, but there is more, something to do with the obsidian blacks produced by the film and with a certain unique drama that made the rock photography of the Sixties and Seventies so powerful and distinctive. Steve Schofield, a British photographer, now in Los Angeles, who first encountered Tri-X in the Seventies, has a different word: “I got these incredibly contrasty negatives that still somehow managed to render detail in both the shadows and highlights. It’s got that steely look, not warm like lots of other film bases. It’s that basic look from Tri-X that I’ve tried to incorporate into my work which is now mostly shot digitally and is now colour…that monochromatic palette, but interpreting it with a simple colour base. If I do ever need to shoot black-and-white, I always prefer film and always opt for Tri-X.”

Another good word is “dirty”. In the early 1950s, monochrome photography was still dominated by the pearly perfection that came in with the black-and-white films of the Thirties. Those pictures had a wide tonal range—many shades of grey—but they tended to look flat. Tri-X, with its narrower tonal range, seldom looked flat and its harder, steelier style fitted the mood first of the realism of the Fifties, then of the casual, go anywhere, do anything mood of the Sixties. This dirtiness—a product both of Tri-X’s grain and its ability to work in low light—was the photographic correlative of three movements in other art forms: the Angry Young Men in literature, the School of London in painting, and the socially engaged work of Lindsay Anderson and Tony Richardson in the cinema. It was an aspect of an age that rejected the cosy, the safe and the merely glamorous in favour of the dynamic, the unstable and the pungent smell of lived life. From this emerged, in the Seventies, Anton Corbijn, perhaps the supreme artist of dirty Tri-X. In his early work, the dirtiness was intensified in the processing and the result was stark, imperfect shots with very visible grain that felt more realistic than any perfectly developed and processed shot.

“Grain is life,” Corbijn says, “there’s all this striving for perfection with digital stuff. Striving is fine, but getting there is not great. I want a sense of the human and that is what breathes life into a picture. For me, imperfection is perfection.”

The urgency of its images made Tri-X the first choice of reportage photographers, from great artists like Cartier-Bresson and McCullin down to the snappers on the local paper. All you needed was a Nikon F camera—expensive but tough and absurdly easy to use compared with today’s professional cameras—and a few rolls of Tri-X and, maybe, a darkroom in your bathroom, and suddenly you could call yourself a photographer.

It should be said that there may have been some magical thinking in all this. Tri-X produced brand loyalty that produced superstitious devotion. Though it was the first fast black-and-white film, it was not on its own for long. Ilford produced a competing 400 ISO film that many regarded as interchangeable with Tri-X and, in any case, long before Photoshop came along, the great darkroom craftsmen could do almost anything with printing and processing. “We could always do what you wanted in the darkroom,” says Mike Spry, a printer at the firm Downtown Darkroom who handled the films of David Bailey, Patrick Lichfield and Anthony Armstrong-Jones (Snowdon). “The great thing about black-and-white as opposed to colour was that you could change things around.”

Though it is true to say that professional digital photography of the face has converged on the dead, waxy, heavily retouched style that dominates the glossy magazines, it should also be remembered that good old-fashioned darkroom technique also involved extensive retouching. The finished product was different but no less manipulated.

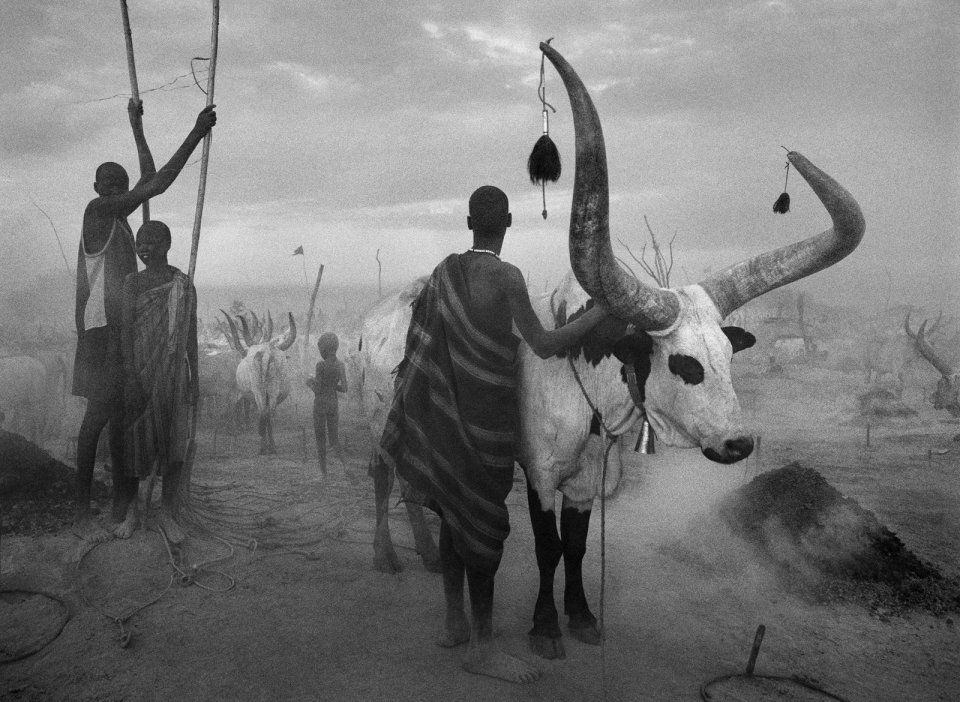

Nevertheless, it was Tri-X that created the possibility and then the demand for urgency, contrast, grain and drama in photography. It revitalised photography as a whole, but black-and-white photography in particular. In doing so it drew attention to the fact that, in spite of the incursion of colour and all the billions of hues and shades of digital, there remains something natural and true about the monochrome photograph, something that springs directly from the camera itself. Sebastião Salgado refuses to consider colour—he regards it as an offensive distraction—and has had his Canon digital cameras adapted so that the screen on the back shows only black-and-white.

It was also thanks to Tri-X that the wave of grainy, dirty reportage pictures changed high art photography. Art photography in the Sixties and Seventies, even in high fashion, was all about dirty grainy realism—and, of course, black-and-white.

“They were great times for printers like me,” Mike Spry says. “Just as hairdressing became an art form in those days, so did black-and-white photography.”

Corbijn’s doctrine that grain is life expresses a great truth about the Sixties and Seventies way of seeing the world. The age was defined by a rebellion against safe perfection and a quest for truth in experimentation, danger and dirt. Nothing captured this moment better than Michelangelo Antonioni’s extraordinary film “Blow-Up” (1966). A Bailey-like photographer called Thomas, played by David Hemmings, makes extreme blow-ups of some monochrome shots he has taken in a park and discovers, emerging ghost-like from the grain, a corpse. But the truth of this corpse—he returns to the park to check that it is really there—contrasts with the bright, high-resolution, high-colour, hallucinated and erotic fantasies of Swinging London. In the end, Thomas is seduced by the unreal. He turns away from the truth of the grain and embraces grainless hippie unreality, a choice symbolised by his willingness to retrieve a non-existent tennis ball. It is hard to imagine a more vivid statement of the legacy of Tri-X and of its centrality not just as a film but as an idea of the age.

In the late 1990s Sebastião Salgado faced a crisis. Ever since the 1960s he had been shooting Tri-X, but he was not sure he could go on—either as a Tri-X user or even as a photographer. He specialises in long, heroic expeditions to produce his astounding pictures, most familiarly of the effects of industry on the third world. As airport security tightened, up to and after 9/11, he found it harder to persuade officials that his cases containing hundreds of rolls of film should be spared the X-ray machines. The signs say these machines do not affect film, but Salgado insists they do, especially if, like him, you pass through six or seven airports in a single trip. “The grain”, he says, “loses its structure.” The people at Kodak, meanwhile, have passed Tri-X through X-ray machines many times and they insist that it is not affected. Salgado, and many other pros, remain unconvinced.

His career and his next great work, “Genesis”, were saved by Canon. They claimed their latest digital cameras could match the quality of film and, after testing in the early 2000s, Salgado agreed. He now shoots everything on digital. Yet this is still a contentious point. Some say it is a simple matter of how many pixels can be packed on a sensor. Film photography, as an analogue form, produces pictures by allowing light to fall on chemically coated celluloid, creating an analogue of the scene in front of the lens. Digital, in contrast, collects light through a series of tiny sensors and then creates an electronic copy of the image. Film has very high resolution and early digital cameras with, say, 5 megapixels—5m sensor points—could not match this. This does not mean their photographs were less realistic, just that they could not be blown up beyond a certain native size without breaking down. For professionals, this makes cropping a digital photograph very costly in terms of available resolution, though software is available that interpolates additional pixels by working out what would be there if the resolution were much higher. Pixel counts have been rising steadily, and both Sony and Nikon now offer cameras for less than £2,000 that deliver 36 megapixels, a level of resolution that probably exceeds the capability of any 35mm film.

But, of course, it is not that simple. Squashing ever more pixels on to a sensor makes for technical problems and, in any case, it may not be the point. Film versus digital, McCullin points out, is still a debate among professionals and they are not talking about megapixels. Film is about more than just resolution, it is about authenticity. Film has other, more mysterious qualities.

“Film has more depth,” Sheila Rock says, “it’s the depth of going into a picture which I don’t find with digital. It’s much flatter. Some say it’s getting much better and I do see some things that have impressed me.”

Salgado knew this and he wasn’t quite prepared to go all the way to the digital look. He still wanted his all black-and-white pictures to look like Tri-X—and they do.

“I went to the exhibition of ‘Genesis’ at the Natural History Museum,” Rock says. “I looked really closely at the pictures and I thought they were Tri-X, but I was told they were digital prints.”

When I asked Salgado how this was done, he shrugged. He did not know: all he did know is that his technicians could produce the Tri-X look he liked. He never touches a computer and his post-production work is done by assistants at his studio in Paris. In fact, and this is a sign of the image-making times, many widely available digital photo-editing programmes now offer “film emulation”. You can simply scroll through a list and pick which type of film you want. Click on Tri-X and your picture will instantly be transformed—grain, drama, dirt and all. It works very—to devotees, alarmingly—well.

This software trickery, inserted into the digital algorithms to mimic an old manual craft, is another symptom of the now familiar phenomenon of analogue defiance, a rebellious hunger for the pre-digital world. Sales of vinyl records are now going up again, resistance to e-books can be fierce and, in New York, an art magazine called Master Cactus has emerged, which is only available on a tape cassette. In photography, the company Lomography has carved out an odd little niche market for plastic and toy film cameras whose dodgy construction produces bizarre and unpredictable effects. Polaroid cameras are on sale again and Fujifilm has produced its own version of instant snappery with the Fuji Instax film. Online, the 100m-plus users of Instagram can apply filters to give their pictures a variety of retro, filmish looks. People seem to be perversely drawn to the shortcomings of film photography—the light leaks of Lomography’s toy cameras, the strange starkness of small Polaroids and even, on Instagram, the corner-vignetting produced by vintage lenses.

Analogue defiance is a real and increasing force in the marketplace. It may be converting only a few to all the hassle and artistry of film, but, as a symbolic statement, it has had enormous impact on camera design. Film cameras, even the most expensive, were simplicity itself with only, in essence, three controls—focus, aperture and shutter speed. Professional or “prosumer” digital cameras have so many controls, it is impossible to list them all. And they are operated by a very user-unfriendly set of buttons. These were discouraging amateurs from trading up, so over the past few years manufacturers, led by Fuji with its X range, have been making retro-looking cameras with old-fashioned wheels and switches. This was so successful that even Nikon, one of the big makers of professional digital cameras, went so far as to produce the Df, a digital camera designed to look like the old Nikon F on which so much Tri-X was shot. It is an absurd and ungainly product costing over £2,700, which, by my reckoning, means you are paying at least £1,000 for the knurled metal knobs on top.

If that all represents a 180-degree turn away from digital perfection, some have gone even further, rejecting the perfect via a kind of 360-degree turn. Google Street View famously, notoriously, set out to photograph all the streets in the world using car-borne digital cameras. Two artists, Michael Wolf and Jon Rafman, decided to use selected images from the millions thus produced to create eerie works of art. These were technically poor photographs, but evocative nonetheless. It was, in its way, an attempt to resurrect the art of street photography, an art taken to a very high level with Tri-X in the hands of photographers like Winogrand and Cartier-Bresson. In their day, street photography was welcomed and safe; now it is dangerous—you can get accused of paedophilia, suspected of being some kind of snooper or, by police, of being a potential terrorist. Even worse, some of your subjects will know all about image rights and release contracts. Street View seemed to solve the problem.

But it was nothing to do with film and most of the analoguesque software gizmos are strictly for amateurs. So the question now becomes: if it can be done digitally right up to the standards required by Salgado, is there any point to Tri-X? Is there any point to film?

There is an old slogan among reportage photographers: “F8 and be there”. F8 is usually the optimum aperture on the lens, the setting that gives the best performance and is most likely to get the shot. “Be there” is just about the absolute necessity of your physical presence at the action. It is the necessity that overrides and underpins all others, so when, in 1948, Cartier-Bresson rushed to take a picture of Nehru announcing the assassination of Gandhi, it did not matter that it was out of focus, ill-lit and streaked with lens flares; all that mattered was that Cartier-Bresson was there to pluck something, anything, from the chaos of events. And, of course, he plucked a masterpiece.

It is this existential truth of photography that professional film-users fear is being lost in the increasingly virtual digital world. “Film is honest,” says Sheila Rock, summarising the views of them all, “Tri-X is honest.” Dishonesty, in this context, can be seen on any newsstand. The business of digital retouching is dictated by the demands of the American star system. Rock, who is obliged to use digital for commercial work, was even told by one client in response to her tastefully retouched images that “American women like to be more perfect”. The result is a universal digital convergence on a style that makes the stars of the covers look like Stepford Wives, robotic and impersonal—they might all be Jennifer Aniston or they might not, it does not matter. Anton Corbijn recently got one of his Tri-X shots into a glossy, but not until they’d asked him if it could be done in colour. He explained that, with film, the shutter click is terminal, at least in this respect.

Corbijn is regarded with envy and awe by many of his peers, but he does not call himself a professional—“there is so much I don’t know”—and he believes in the power of limitation to increase your creativity. This is why he sticks to film: it does not have the vast flexibility of digital, a flexibility that detracts from the power of the moment when the shutter fires. He is passionate about the material process of making a photograph from film.

“When I started, I felt that I didn’t want a normal job in photography, I wanted that sense of adventure when you meet someone and take a picture. I felt that digital is more like a job. You look at the screen to see if you have it right, then you take another picture. When I come back from a trip, I don’t know what I have exactly. I have to get it developed, so I won’t know for a couple of days. I like the tension of not knowing exactly what you have.”

“There’s nothing like going to Vietnam,” says McCullin, echoing the thought, “when I had to sit on the film for six weeks with a mental memory of the images I took. I had to be patient and carry all that film back to England. It became more precious by the week. And then you went to the lab wondering whether what you had was as good as what you thought you had. The waiting and the torment gave an edge to the whole procedure. Now, with digital cameras, you are looking at the screen on the back after every shot. It becomes an instant thing like fast food, it takes something away from the original menu.”

On top of that thrilling anguish, there is the manual craft of the darkroom where either the photographer himself or his trusted technician would use a bewildering array of methods—“ducking and weaving with bits of wire and stuff,” McCullin says—to manoeuvre the image as close as possible to the one in the artist’s head.

All this is being lost as darkrooms close and companies stop producing one type of film after another. Of course, many things are gained, but the full cost of digitalization in many fields, not just photography, is yet to be accounted. Kodak say that film in general and Tri-X in particular is safe. Yet I felt a pang when I asked how they were going to celebrate the diamond jubilee of their greatest film, and they said they had “no definitive plans we can share as of today”.

Never mind, we can do it for them by remembering Tri-X’s black-and-white golden age and celebrating its continuation in the works of Salgado, Rock, Corbijn and, of course, McCullin, the old master. He was off to India when we spoke.

“An Indian dawn with Tri-X,” he said, “it’s like being in heaven.”

Happy birthday, Tri-X, and many more of them.

Justifying the Purchase of a Leica

In one version of our lives, childhood is a series of deprivations and desires whereby we want things we can’t have, some of which we grow out of or just forget. In my case, I was seized with heartache when I entered the newly opened 8,000-square-foot Leica store on Beverly Boulevard at Robertson in West Hollywood. Until then, I had forgotten how much I wanted to own a Leica….

…My own passion for photography and for cameras was kindled by a summer job, at 13, in a midtown Manhattan camera store run by Hungarian Jewish émigrés. Back then, there was a hierarchy to everything, including desire. The serious young photographer graduated from taking snapshots to a single-lens reflex camera, such as a Mamiya Sekor (popular among my friends), or, if you were more affluent, a Pentax. From there you graduated to an Olympus, and then a Nikon. Professionals used professional versions of the Nikon — which were all black. For the truly discerning, however, the object of desire was the Leica.

The Leica felt solid and was fully manual (a plus to the camera geek), allowing for maximum choice, and therefore, maximum artistic control in each photo. It sat in your hand with a satisfying heft, a solidness that spoke to its seriousness of purpose. To me, it was the embodiment of the schwarzgerat (literally “the black device”), a finely tooled exemplar of German engineering so satisfying in its design and manufacture, so intelligently made, that its use gave pleasure and conferred status and excellence on the user. The reverence in which the schwarzgerat is held has been central to several contemporary classics such as the black monolith in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 or the secret component in the searched-for rocket in Thomas Pynchon’s “Gravity’s Rainbow.” I aspired to the Leica, although I knew it was way out of my league.

Everything about it said “German,” which might have added to its forbidden-fruit status, as my parents, Holocaust memories ever fresh, didn’t buy German. However, just as the overwhelming quality of the product convinced some Jews to drive Mercedes and BMWs, particularly after Israel accepted the wiedergutmachung — reparations from Germany — Leica was adopted by many Jewish photographers, among them Robert Capa and Cornell Capa.

Jewish guilt was further assuaged by an e-mail that has been making the rounds for the last several years (I’ve received it as least three times from three different sources), variously referred to as “Leica and the Jews” or “The Leica Freedom Train.” The e-mail tells of how, as the Nazis came to power, Ernst Leitz II, son of the founder, arranged for his Jewish employees to leave Germany. He strung Leicas over their necks and dubbed them Leica sales agents, allowing them to obtain travel visas when those were increasingly hard to get. The cameras themselves served as proof and were a valuable commodity upon arrival in a foreign land. In many cases, Leitz personally arranged introductions to photo businesses in the United States and other countries for his employees. This continued until 1939, when Germany closed its borders to all Jews. Even after that, Leitz’s daughter was involved in helping to smuggle Jews into Switzerland. As Protestants, Leitz said, it was just the right thing to do and he never sought any acclaim for his actions.

A spirit more truculent than mine might point out that Leica did not close its factories under the Reich, or move its operations to the United States or England — to the contrary, Leica optics were very valuable to the German war effort, and Leitz remained a Nazi party member. And although the company was never convicted of using slave labor, in 1988 it voluntarily paid into a fund set up for German companies to compensate former slave laborers. But this does not make what Leica did for its Jewish employees prior to 1939 any less true: Those “Leica Jews,” their children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren are alive because of the opportunity Leitz gave them…

…For many years, though, Leica had been off my radar. Then I walked into the Leica megastore, a gleaming cube, replete with an upstairs gallery space showing the works of celebrated portrait photographer Mary Ellen Mark, Seal (yes, the singer, who is a brand ambassador for the company, as well as an accomplished photographer with special access to nude models lying on hotel room beds) and Yariv Milchan, the landscape and celebrity photographer (whose Hollywood connection is genetic — his father is entertainment mogul Arnon Milchan). It also houses a bookstore selling rare and well-chosen photo books, curated by Martin Parr of Magnum. And, finally, there are the cameras…

….One might think this would be the worst possible time to be selling expensive cameras. In the last few years, images made using smartphones and iPhones posted on Instagram, Snapchat and Facebook have made everyone a photographer or a photodiarist of their meals, pets, friends and selves. Hasn’t digital and the Internet disrupted and leveled photography?

James Agnew, the store’s general manager, sees it differently. He believes the ubiquity of photos has created a backlash, and he believes there is “overall a return to the tradition of photography and a renewed call for quality cameras and images.”

What became clear from talking with Agnew — who prior to opening this new Leica store, worked for such luxury retailers as Giorgio Armani, Chanel and Van Cleef & Arpels — is that Leica is positioning itself as a luxury company. We live in a society where driving a Bentley rather than a Prius (or, rather, driving a Bentley in addition to a Prius) is a choice that the marketplace supports. So, for every 1,000 or 10,000 iPhone photo enthusiasts, there will be some who crave, or succumb to, the quality and the allure of a Leica.

And if they can’t afford one, then, like me, they can spend time at the beautiful new Leica megastore, lusting for excellence.

Tom Teicholz is a film producer in Los Angeles. His blog can be found at jewishjournal.com/tommywood.

Bruce Davidson and the Girl With the Kitten

In 1960, American documentary photographer Bruce Davidson captured this image of a young woman holding a kitten.

I always had a feeling for Britain. We would listen to the BBC during the war, when I had an uncle Herb who was flying a bomber, which I believe may have been from England.

In 1960, I purchased a Hillman Minx convertible, which wasn’t a very expensive car in those days, and drove around England with the top down. It was an American-drive car, which was an advantage because I could snap people on the sidewalk more easily. I also had a sports coat made with the side pockets larger, so I could fit my Leicas in them.

I found this young woman quite by accident, as I was walking the London streets. I came upon a group of teenagers, and struck up a conversation. They took me into a cave, and then some kind of huge dancehall. I think it was on an island. It was getting late, and I needed to move on the next morning, so I didn’t stay very long.

But I isolated this girl to photograph, holding that kitten, which was probably a stray she had found on the street, and carrying that bedroll wrapped around her body. There was a great deal of mystery to her. I didn’t know where she had come from, and I didn’t get her name, but there was something about that face – the hopefulness, positivity and openness to life – it was the new face of Britain.

The picture was taken with a normal 50mm lens, with a wide aperture. I used the Ilford film, called HPS – hyper-sensitive film – which I loved, although it is probably no longer made. I loved that grainy texture; she has the feeling of a statue.

I still feel close to this picture. I wonder what that young girl is doing now. She must be lurking around London someplace, or she may not be alive, you never know.

Bruce Davidson’s Black Paint Leica M2

How to Become a Photographer

Following is a letter written by Magnum photographer Sergio Larrain in 1982 to his nephew, who had asked Larrain for advice on how to become a photographer:

First and foremost, find a camera that fits you well, one that you like, because it’s about feeling comfortable with what you have in your hands: the equipment is key to any profession, and it should have nothing more than the strictly necessary features.

Act like you’re going on an adventure, like a sailing a boat: drop the sails. Go to Valparaiso or Chiloè, be in the street all day long, wander and wander in unknown places, sit under a tree when you’re tired, buy a banana or some bread and get on the first train, go wherever you like, and look, draw a bit, look. Get away from the things you know, get closer to those you don’t know, go from one place to the other, places you like. Then, you’ll start finding things, images will be forming into your head, consider them as apparitions.

\When you get back home, develop, print and start looking at what you’ve done, all of the fish you’ve caught. Print your photos and tape them to a wall. Look at them. Play around with the L, cropping and framing, and you will learn about composition and geometry. Enlarge what you frame and leave it on the wall. By looking, you will learn to see. When you agree that a photograph is not good, throw it out. Tape the best ones higher on the wall, and eventually look at those only (keeping the not-so-good one gets you used to not-so-goodness). Save the good ones, but throw everything else away, because the psyche retains everything you keep.

Then use your time to do other things, and don’t worry about it. Start studying the work of others and looking for something good in whatever comes into your hands: books, magazines, etc. and keep the best ones, and cut them out if you can, keep the good things and tape them to the wall next to yours, and if you can’t cut them out, open the book or magazine at the good pages and leave it open. Leave it there for weeks, months, until it speaks to you: it takes time to see, but the secret will slowly reveal itself, and eventually you will see what is good and the essence of everything.

Go on with your life, draw a bit, take a walk, but don’t force yourself to take photographs: this kills the poetry, the life in it gets sick. It would be like forcing love or a friendship: you can’t do it. Take a new journey: go to Porto Aguire, ride down the Baker to the storms in Aysén; Valparaiso is always beautiful, get lost in the magic, get lost for days up and down its slopes and streets, sleep in a sleeping bag, soak in reality – like a swimmer in the water – and let nothing conventional distract you.

Let your feet guide you, slowly, as if you were cured by the pleasure of looking, humming, and what you will see you will start photographing more carefully, and you will learn about composition and framing, you will do it with your camera, and your net will be filled with fish when you arrive home. Learn about focus, aperture, close-ups, saturation, shutter speed. Learn how to play with your camera and its possibilities. Collect poetry (yours and that of others), keep everything good you can find, even that done by others. Make a collection of good things: like a small museum in a folder.

Photograph the way you like it. Don’t believe in anything but your taste, you are life and it’s life that chooses… You are the only criterion. Keep learning. When you have some good photos, enlarge them, make a small exhibition or put them in a book and have it bound. Showing your photographs will make you realize what they are, but you will understand only when you will see them in front of others. Making an exhibition is giving something, like giving food, it’s good that others are shown something done with seriousness and joy. It’s not bragging, it’s good for you because it gives you feedback.

That’s enough to start. It’s about vagabonding, sitting down under a tree anywhere. It’s about wandering in the universe by yourself: you will start looking again. The conventional world puts a veil over your eyes, it’s a matter of taking it off during your time as a photographer.

Missing That Iconic Shot While Loading Your Leica

David Burnett, Washington Post, June 12, 2012:

It’s difficult to explain to someone who has grown up in the world of digital photography just what it was like being a photojournalist in the all-too-recently-passed era of film cameras. That there was, necessarily, a moment when your finite roll of film would end at frame 36, and you would have to swap out the shot film for a fresh roll before being able to resume the hunt for a picture. In those “in between” moments, brief as they might have been, there was always the possibility of the picture taking place. You would try to anticipate what was happening in front of your eyes, and avoid being out of film at some key intersection of time and place. But sometimes the moment just wouldn’t wait. Photojournalism — the pursuit of storytelling with a camera — is still a relatively young trade, but there are plenty of stories about those missed pictures.

In the summer of 1972, I was a 25-year-old photojournalist working in Vietnam, mostly for Time and Life magazines. As the United States began winding down its direct combat role and encouraging Vietnamese fighting units to take over the war, trying to find and tell the story presented enormous challenges. On June 8, a New York Times reporter and I were going to explore what was happening on Route 1, an hour out of Saigon. We visited a small village that had seen some overnight fighting, but were told by locals that there was a bigger battle going on a few kilometers north. There, at the village of Trang Bang, I waited and watched with a dozen other journalists from a short distance as round after round of small-arm and grenade fire signaled an ongoing firefight. I was changing film in one of my old Leicas, an amazing camera with a reputation for being infamously difficult to load. As I struggled, a Vietnamese air force fighter came in low and slow and dropped napalm on what its pilot thought were enemy positions. Moments later, as I was still fumbling with my camera, the journalists were riveted by faint images of people running through the smoke. AP photographer Nick Ut took off toward the villagers who were running in desperation from the fire.

In one moment, when Ut’s Leica came up to his eye and he took a photograph of the badly burned children, he captured an image that would transcend politics and history and become emblematic of the horrors of war visited on the innocent. When a photograph is just right, it captures all those elements of time and emotion in an indelible way. Film and video treat every moment equally, yet those moments simply are not equal.Within minutes, the children had been hustled into Nick’s car and were en route to a Saigon hospital. A couple of hours later, I found myself at the Associated Press darkroom, waiting to see what my own pictures looked like. Then, out from the darkroom stepped Nick Ut, holding a small, still-wet copy of his best picture: a 5-by-7 print of Kim Phuc running with her brothers to escape the burning napalm. We were the first eyes to see that picture; it would be another full day before the rest of the world would see it on virtually every newspaper’s Page 1.

***

After Trang Bang, my sense of being “photographer ready” was more acute; the instinct has served me well in dozens of stories since. You never really know what is going to happen next. Anticipating what could happen, what might happen, those are the keys to being a great photographer.

And yet, even with those lessons uppermost in my mind, there were times when I simply didn’t anticipate what might happen.

In March 1979, having just returned days before from covering the Revolution in Iran, I found myself in a key “pool” position at the White House North Lawn. It was the official signing of the Camp David peace accords, negotiated by President Carter, between Egypt and Israel. It was a historic day, with plenty of television and photo coverage. I was carrying my own three cameras, plus one each from two other photographers, as I was given a good spot, head-on, from which to see the three dignitaries: Carter, Begin and Sadat. Once they walked onto the outdoor stage, I began shooting. I shot madly as they signed the documents and passed the papers among themselves. And at the magic moment, after they had all put down their pens, they stood up and unexpectedly embraced, hand over hand, all round, with gusts of wind fluttering the three giant flags behind them. This was the picture. As I grabbed for one of my cameras, I realized the roll was completely shot. I grabbed the next camera: same result. And then the third, fourth and last cameras. Panic. I was out of film in all five cameras, and even with motorized loading was still at least 25 or 30 seconds away from being able to make a picture.

There were no more groundbreaking handshakes. No more diplomatic embraces. It was over, and I had no pictures of that day that, to me, spoke to the event itself.

In the new digital age of 1,000-plus pictures on a memory card, running out of “film” is less likely. But being aware is still what photography is about. Being able to see that bigger world and your place in it. And knowing that, at any time, a picture could take place. So, today, I try to always have a few frames of film left, and plenty of space on my memory card. Always.

Nick Ut’s Recollections of Trang Bang

Nick Ut, 1966, Viet Nam

Nick Ut, 1966, Viet Nam

In year 7 of the war, I heard the story about heavy fighting in Trang Bang. Lots of people were fighting on highway one and they had locked down the highway. They were fighting like they were on the first day. So I told a friend of mine that I wanted to go there the next day in the early morning. At 7:30 the following morning I saw 1,000 victim refugees on the highway, many of them running. I took a lot of pictures of refugees running, and you could see the black smoke from the bombs all morning. I followed the 25th division away from the highway 2 miles away. When I went back to the highway I saw dead bodies everywhere. So I wanted to head back to AP Saigon because I had many pictures ready. That was when I noticed one Vietnamese soldier. He had thrown a smoke grenade, which erupted in yellow smoke. Then you could hear a jet come in and dive down and drop two bombs. Immediately there were two explosions. It was very noisy. And then a sky-rider dove and dropped napalm. And I shot the picture and it looked really good because I shot in black and white, not color. I took the picture and then everyone was running furiously; I had taken the picture before anyone had realized what happened. Then a woman carrying a baby came running. She is asking for help. Her grandson was dying and he was only a year old. I used my Leica to take a picture and the boy died right in front of my camera. Then I saw the naked girl, Kim, running and I ran inside right away. I took a lot of pictures. And when she passed me I saw a lot of her skin coming off. I knew she was going to die. I put my camera down on the highway and put water on her body right away. She told me no more water. I told her it was just drinking water. But she said in Vietnamese, “Too hot! Too hot! I think I’m dying”

She told her brother she thought she was dying also. But they kept running for another ten minutes and then I told her I wanted to help her. My friend from the BBC assisted with the water bottle. Then I borrowed a raincoat for her body since she was naked. I picked her up and put her in my car with all the children already inside the car. She kept telling me she was dying. I knew she was dying, but I wanted to take her to a good hospital. And the people at the hospital wanted to help her too. But the local hospital was too small. When I got there I showed them my media pass and said if these children die your picture will be on the front page tomorrow and you might be out of a job, and they were worried. Well, we got all the children into the hospital, but then I started worrying about my pictures. I held my camera and looked at it to see how many frames I had taken. I knew that number 7 would be a good shot. When I got to the AP office I told them I had a very important roll of film. I asked them to please help me develop it, so we went into the darkroom immediately. We developed all my pictures and after looking at the first photo they asked me why I shot a picture of a naked girl. I said no, it was the result of a napalm bomb. You can see it exploding. We made one 5 x7 print of it and waited for Horst to come back so we could show him the picture. I wound up talking all week about that picture. New York and Vietnam said good job. And that morning Horst and I went back to do a story about what had happened with the napalm. Later we saw Kim’s father running around looking for her. I told him she might be dying in a hospital. He screamed and then he took a small car to the hospital right away. I went back to the hospital and I saw her parents. Her father thanked me and said I saved his daughter’s life.

William Eggleston Mails It In From Paris

I’ve been lucky enough to have lived in Paris. It was one of the formative experiences of my life. I spent countless hours walking the streets with a camera, looking, not always successfully, for interesting ways to visually capture my impressions of the city while avoiding the standard photographic cliches.

Paris is not an easy city to photograph. Its surface charms easily lend themselves to cliche. Certainly, Paris has its quick and easy visual charms, but Atget, Lartigue, Brassai, Ronis, Cartier-Bresson, Boubot, Koudelka and many more have seemingly exhausted a picturesque presentation of Paris. The last thing the world needs is another photographer recycling the same tired Parisian visual tropes.

So I was mildly surprised when, visiting Paris last Fall, I found a monograph of William Eggleston’s photographs of Paris on my Parisian friend’s bookshelf. “Never heard of it, ” I mentioned to my friend Jorge as I pulled it from its place on the shelf and opened it. “Its junk, the sort of crap you get to publish because you’re famous,” Jorge replied.

William Eggleston Paris is the result of an invitation from the Foundation Cartier Pour l’Art Contemporain in Paris to Eggleston to photograph the city and exhibit the results at the Foundation. In their notes advertising the finished project, they claim Eggleston spent three years working on the project. If you read the end notes carefully, you’ll discover he actually spent only a few weekends in Paris photographing. It shows. The work has all the superficiality of a bus tourist’s idealized idea of “The City of Light.” Give any aesthetically interested teenager an iPhone with an Instagram app and a few long weekends in Paris and they’d crank the same photos out endlessly. The difference, them not being William Eggleston, nobody would give them prime space in Paris to exhibit it, let alone publish and promote it internationally.

Some photographers’ excellence is inextricably bound to a time and place: Atget’s and Brassai’s Paris, Winogrand’s New York City, Harvey Stein’s Coney Island, Paul Kwilecki’s small town Georgia. Memphis born Eggleston’s appeal has always been his use of color to present his laconic vision of American fly-over territory – the banalities of capitalist consumer culture. His “genius”, if we can call it that, was to see the role color played in the States in a way it doesn’t elsewhere, its vulgarity and ugliness when co-opted to sell things or to brighten lives made dull by the false promise of American consumerism. Speaking of his discovery of color, Eggleston remembered the day he “got it”: he decided one day to go to a large Memphis supermarket and take pictures of the shoppers, so American. He unwittingly overexposed the day’s film, and when he had them developed he saw the hidden meaning of the color pop out at him: “the first frame, I remember, was some kid pushing grocery carts. Some kind of pimply, freckle faced guy in the late sunlight.” Perfect.

As for the Paris pictures, its hard to fault Eggleston for their failure. Knowing his dry humor, I half suspect he considered himself in on the joke. The fault really lies with the person whose idea it was commission the project. What could Eggleston’s aesthetic, so tied to its American context for its effect, have to say about a city and culture he could only know as a tourist? Expecting Eggleston to have a coherent, mature vision of Paris, simply because he’s William Eggleston, is wooly headed at best.

Eggleston’s failed Parisian adventure should remind us of the vital importance of context to good photography. The best, Eggleston’s included, is the result of an idiosyncratic vision, often tied to a specific time or place, the time or place usually being an integral component of the idiosyncrasy. Subtract the time, or the place, and the vision it spawns, and you are left with mere photographs. Anybody with an iPhone can take a photograph.

And that’s ultimately what makes photography such a simple yet deceptively difficult aesthetic undertaking. It seems so easy: buy a good camera with a good lens and find interesting things to photograph; make sure the pictures are sharp, the colors are vivid, the appropriate things are in focus, and the visual elements interestingly arranged. Post your best work on Tumblr. You may get an exhibition of your work at the local cafe. The only problem is you’ll still have nothing to say, and you’ll never, in 50 years of shooting pictures, produce one picture like the one below, because you didn’t have the vision to look for it and you wouldn’t have recognized it if you saw it:

In my time in Paris, my friend Jorge and I made a habit to see as much work in exhibitions and galleries as we could. Most of it, even the wildly celebrated, frankly wasn’t very good. Some of it, like Antoine D’Agata’s work at VU gallery, was magnificent, instantly recognizable as quality stuff. After years of looking, we jokingly encapsulated what we learned in a few simple rules. Rule 1: Have something to say. Rule 2: If you don’t have anything to say, make your prints really big. Rule 3: If that doesn’t work, make your photos really colorful. Eggleston’s Paris photos follow all three Rules.

In Eggleston’s best work, the work that made him famous, color is intrinsic to the meaning of the photograph. Its not simply a garnish to draw the eye. His best photographs are not ‘about’ the color; they are about larger issues that the color is used in the service of. This is whats missing in his Paris pictures. The color here is pure ornament, eye candy to seduce you into forgetting that the picture has nothing to say.

Robert Frank Gets Arrested Down South

In November 1955, Lt RE Brown of the Arkansas State Police spotted an unshaven and shabbily dressed suspicious looking man driving an old Ford near the Mississippi River.The man’s car was full of maps, numerous papers written in foreign languages, and a number of strange German “Leica’ cameras with bags and bags of exposed films. Suspecting the man to be a communist spy, Lt Brown arrested Robert Frank and brought him to the McGehee City jail for fingerprinting and interrogation. A local citizen “who knew several foreign languages” was brought in to assist in Frank’s questioning even though Frank spoke fluent English.

The Swiss-born Frank protested that he was a professional photographer who had received a grant to travel America taking pictures. He explained that his work had been published in the New York Herald Tribune, the New York Times and Life and Look magazines. Frank showed the Lt. some of his work, what looked to Lt. Brown like spy photos: blurry images, often out of car windows, of things like bridges, factories and power stations. It was only when Frank produced a well worn copy of Forbes magazine with his name and photos prominently displayed was he finally allowed to go on his way. His fingerprints were forwarded to the FBI.

Four years later, in 1959, some of the same pictures he showed Lt Brown would be published in book form in Frank’s seminal work The Americans.

ARKANSAS STATE POLICE

Little Rock, Arkansas

December 19, 1955

Alan R. Templeton, Captain

Criminal Investigations Division

Arkansas State Police

Little Rock, Arkansas

Dear Captain Templeton:

On or about November 7, I was enroute to Dermott to attend to some business and about 2 o’clock I observed a 1950 or 1951 Ford with New York license, driven by a subject later identified as Robert Frank of New York City.

After stopping the car I noticed that he was shabbily dressed, needed a shave and a haircut, also a bath. Subject talked with a foreign accent. I talked to the subject a few minutes and looked into the car where I noticed it was heavily loaded with suitcases, trunks and a number of cameras.

Due to the fact that it was necessary for me to report to Dermott immediately, I placed the subject in the City Jail in McGehee until such time that I could return and check him out.

After returning from Dermott I questioned this subject. He was very uncooperative and had a tendency to be “smart-elecky” in answering questions. Present during the questioning was Trooper Buren Jackson and Officer Ernest Crook of the McGehee Police Department.

We were advised that a Mr. Mercer Woolf of McGehee, who had some experience in counter-intelligence work during World War II and could read and speak several foreign languages, would be available to assist us in checking out this subject. Subject had numerous papers in foreign langauges, including a passport that did not include his picture.

This officer investigated this subject due to the man’s appearance, the fact that he was a foreigner and had in his possession cameras and felt that the subject should be checked out as we are continually being advised to watch out for any persons illegally in this country possibly in the emply of some unfriendly foreign power and the possibility of Communist affiliations.

Subject was fingerprinted in the normal routine of police investigation; one card being sent to Arkansas State Police Headquarters and one card to the Federal Bureau of Investigation in Washington.

Respectfully submitted,

Lieutenant R.E. Brown, Lieutenant Comanding

Troop #5

ARKANSAS STATE POLICE

Warren, Arkansas

Allen Ginsberg’s Leica Selfie

I didn’t know much of Allen Ginsberg before reading Bill Morgan’s excellent 2008 biography I Celebrate Myself. Ginsberg seemed at best a minor talent in a discipline I knew little about, at worst a mentally ill crank. But Morgan’s book drew me in deeper and deeper, and I soon saw the genius of Ginsberg, a genius manifested in both his art and his life, which I assume Ginsberg would say were one and the same. Ginsberg’s humanity shines through in Morgan’s work – generosity, kindness, creativity, eccentricity, but mostly a dedication to live fully and richly without excuse. In this age of greedy hucksters passing as ‘artists’, Ginsberg was the real deal. A fascinating human being in the best sense of the word.

So I was particularly interested when The National Gallery of Art published Beat Memories: The Photographs of Allen Ginsberg. From the late 40’s through the early 60’s, Ginsberg made many photographs of his Beat friends – Kerouac, William Burroughs, Neal Cassady, Gregory Corso – and did so with a great photographic eye and an uncanny sense of the importance of everyday events, what he referred to as “certain moments in eternity.” The photographs were meant for his private use, “keepsakes” with no further value than as personal documents of private moments.

Apparently Ginsberg put down his camera in 1963 and didn’t routinely pick it up again til the 1980’s, when, with the help of his friend Robert Frank, he edited and printed a series for exhibition at the Holly Solomon Gallery in New York. Adding extensive handwritten inscription on each exhibition print, the series is quotidian documentary photography at its best – immediate, warm, human, casual, funny, sad – and always visually arresting in its lack of artifice.

Ginsberg, ever humble, questioned the importance of his photographs and deferred questions about this aspect of his creativity by agreeing with Robert Frank’s assertion that “photography was an art for lazy people.” And it can be. But the best photography, work like Ginsberg’s, transcends the simplicity of its making and gives us something new to see, something that is more than the sum of what it represents.

“Leica Photography” Is Dead. Leica Killed It.

Above are two of my favorite photographs from two of the twentieth century’s most skilled and creative photographers. Both are powerfully evocative while being deceptively banal, commonplace. A dog in a park; a couple with their child at the beach. Both were taken with simple Leica 35mm film cameras and epitomize the traditional Leica aesthetic: quick glimpses of lived life taken with a small, discrete camera, what’s come to be known rather tritely as the “Decisive Moment.”

Looking at them I’m reminded that a definition of photographic “quality” is meaningless unless we can define what make photographs evocative. In the digital age, with an enormous emphasis on detail and precision, most people use resolution as their only standard. Bewitched by technology, digital photographers have fetishized sharpness and detail.

Before digital, a photographer would choose a film format and film that fit the constraints of necessity. Photographers used Leica rangefinders because they were small, and light and offered a full system of lenses and accessories. Leitz optics were no better than its competitor Zeiss, and often not as good as the upstart Nikkor optics discovered by photojournalists during the Korean War. The old 50/2 Leitz Summars and Summitars were markedly inferior to the Zeiss Jena 50/1.5 or the 50/2 Nikkor. The 85/2 and 105/2.5 Nikkors were much better than the 90/2 first version Summicron; the Leitz 50/1.5 Summarit, a coated version of the prewar Xenon, was less sharp than the Nikkor 50/1.4 and the Nikkor’s design predecessor the Zeiss 50/1.5. The W-Nikkor 3.5cm 1.8 blew the 35mm Leitz offerings out of the water, and the LTM version remains, 60 years later, one of the best 35mm lenses ever made for a Leica.

But the point is this: back when HCB and Robert Frank carried a Leica rangefinder, nobody much cared if a 35mm negative was grainy or tack sharp. If it was good enough it made the cover of Life or Look Magazine. The average newspaper photo, rarely larger than 4×5, was printed by letterpress using a relatively coarse halftone screen on pulp paper, certainly not a situation requiring a super sharp lens. As for prints, HCB left the developing and printing to others, masters like my friend and mentor Georges Fèvre of PICTO/Paris, who could magically turn a mediocre negative into a stunning print in the darkroom.

50’s era films were grainy, another reason not to shoot a small negative. Enthusiasts used a 6×6 TLR if they needed 11×14 or larger prints. For a commercial product shot for a magazine spread the choice might be 6×6, 6×7, or 6×9. Many didn’t shoot less than 4×5. If you wanted as much detail as possible, then you would shoot sheet film: 4×5, 5×7 or 8×10.

What made the ‘Leica mystique’, the reason why people like Jacques Lartigue, Robert Capa, HCB, Josef Koudelka, Robert Frank and Andre Kertesz used a Leica, was because it was the smallest, lightest, best built and most functional 35mm camera system then available. It wasn’t about the lenses. Many, including Robert Frank, used Zeiss, Nikkor or Canon lenses on their Leicas. It was only in the 1990’s, with the ownership change from the Leitz family to Leica GmbH, that Leica reinvented itself as a premier optical manufacturer. The traditional rangefinder business came along for the ride, but Leica technology became focused on optical design. Today, by all accounts, Leica makes the finest photographic optics in the world, with prices to match.

Which leads me to note the confused and contradictory soap boxes current digital Leicaphiles too often find themselves standing on. Invariably, they drone on about the uncompromising standards of the optics, while simultaneously dumbing down their files post-production to give the look of a vintage Summarit and Tri-X pushed to 1600 iso. Leica themselves seem to have fallen for the confusion as well. They’ve marketed the MM (Monochrom) as an unsurpassed tool to produce the subtle tonal gradations of the best B&W, but then bundle it with Silver Efex Pro software to encourage users to recreate the grainy, contrasty look of 35mm Tri-X. The current Leica – Leica GmbH – seems content to trade on Leica’s heritage while having turned its back on what made Leica famous: simplicity and ease of use. Instead, they now cynically produce and market status.

For the greats who made Leica’s name – HCB, Robert Frank, Josef Koudelka – it had nothing to do with status. It was all about an eye, and a camera discreet enough to service it. They were there, with a camera that allowed them access, and they had the vision to take that shot, at that time, and to subsequently find it in a contact sheet. That was “Leica Photography.” It wasn’t about sharpness or resolution, or aspherical elements, or creamy bokeh or chromatic aberration or back focus or all the other nonsense we feel necessary to value when we fail to acknowledge the poverty of our vision.

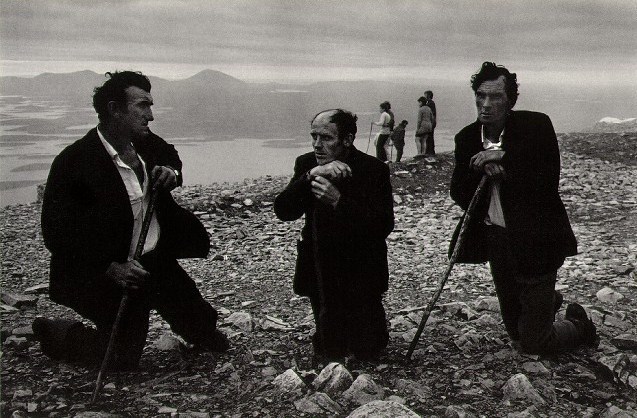

Koen Wessing: Duality as Photographic Punctum

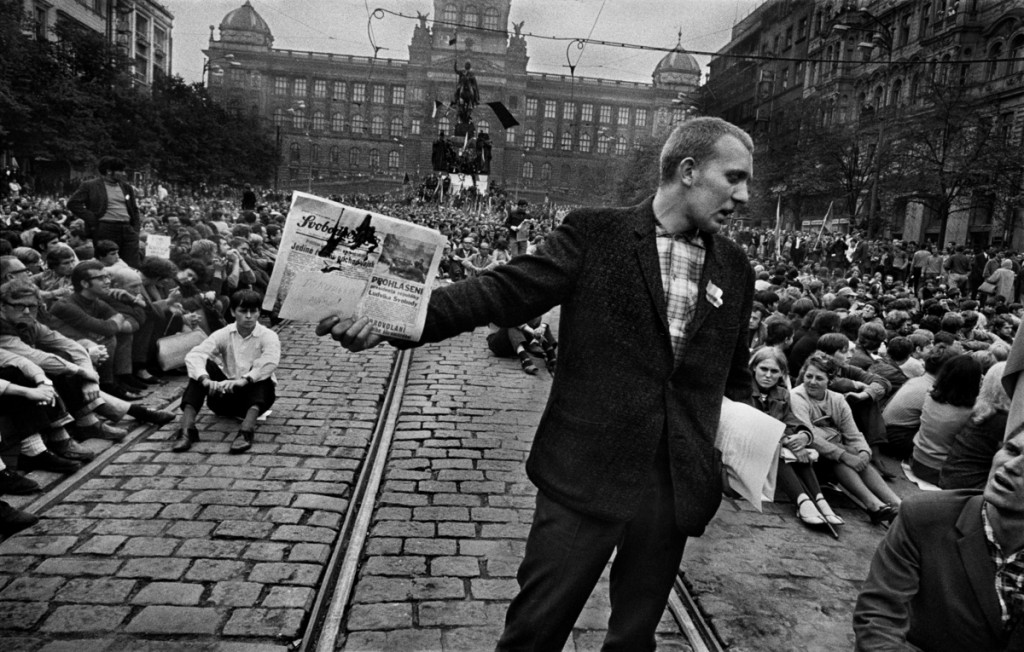

Koen Wessing was a Dutch photojournalist best known for his work photographing Chile’s 1973 mititary coup. Wessing was first attracted to photography after reading Weegee’s Naked City. He started as freelance photographer in 1963. In the 60’s he served a stint as a printer for Magnum. He first won recognition for his own pictures of the May protests in Paris in 1968 and the occupation of the Maagdenhuis of the University in Amsterdam in 1969. His images of the 1973 coup in Chile against the progressive government of Salvador Allende, taken with a Leica M4, made him an internationally renowned photographer.

Roland Barthe, in his seminal work Camera Lucida, discusses at length one of Wessing’s 1979 photos from Nicaragua that depicts two nuns walking past armed soldiers. The juxtaposition — or duality, as Barthes calls it — is noteworthy to Barthes; it is this duality that creates the picture’s punctum, the thing that makes the viewer pause and look again.

Koen Wessing passed away in Amsterdam on February 2, 2011. He was in the process of hanging prints for an upcoming retrospective of his work in Santiago.

Good Advice

“I have a bit of advice for anyone getting into photography for the first time: practice with a digital camera then as soon as you can buy a roll of film and load it into a Leica, any Leica, even an old beat-up one. Then start taking pictures. You’ll find the experience very special, a little magical. You’ll find yourself part of the world.”

—Gianni Berengo Gardin, 2012

Leica Selfie #21

The Leica M3D

Leica M3D black paint, November 2012 (1955, serial number M3D-2)

Only 4 M3D’s (M3D-1 to M3D-4) were produced by Leitz. All were custom made for LIFE magazine photojournalist David Douglas Duncan. Each was mated to a black Leicavit without the standard MP engraving. (Note the auxiliary rewind crank, presumably added by Duncan after the fact.)

If you see one on Ebay at a decent “Buy It Now” price, snap it up quick (don’t expect it to be described as “Minty” however). This M3D, with Leicavit and Summilux, was sold at auction on November 24, 2012 for 1,680,000 Euros.

Robert Capa’s Leica

A wonderful Leica promotional video with Robert Capa as the photographer/protagonist. There’s only one problem: Robert Capa didn’t shoot his iconic WW2 photographs with a Leica. He used a Contax.

Garry Winogrand’s M4

Born in 1928 and died in 1984, Winogrand is considered by many to be one of the most influential American photographers of the 20th century. By the early 1970’s when he purchased this M4, he was shooting roughly 1000 rolls of film a year, a pace he accelerated until his death from cancer in 1984.

While Winogrand is known for his wide angle vision (many of his iconic photos were taken with a 28mm Elmarit) he typically carried two camera bodies with him, one with a 28 and one with a moderate telephoto. This particular M4 was produced in Wetzler in November, 1970, which means it probably saw 12 years and approximately 15,000 rolls of concentrated use by Winogrand.

According to Stephen Gandy, this M4 passed to one of Winogrand’s friends, who still uses the camera. I’m pretty certain Winogrand would have wanted it that way.

W. Eugene Smith and Five Stolen Leicas

“Fate, it not only reigns, it gores. Ah yes, that film that working the nights into long days I did develop, I did complete, and from exhaustion I did collapse. That film (the second half of it, about 500 pictures) all packed and boxed and ready for mailing, was stolen from my car yesterday.”

W. Eugene Smith in a letter to his brother Paul, May 1955.

On May 20, 1955, someone broke into LIFE photographer W. Eugene Smith’s car while it was parked in downtown Pittsburgh. The thieves carried off 5 Leica cameras (a mixture of If, IIf and IIIfs), 10 lenses, and a box of exposed films he had shot for his now iconic documentary project about Pittsburgh.

Local newspapers and the Pittsburgh police subsequently circulated requests to the thieves to return the film, as it represented the sum total of a month of shooting by Smith. They were told they could keep the Leicas. Two of Smith’s Leica showed up in a local pawn shop, where Smith bought them back for $40. One of the cameras contained a roll of film that, once developed, showed the thieves taking pictures of each other. The pictures were used to eventually arrest the culprits, and the remainder of Smith’s equipment was found in their possession. Smith would use these 5 Leicas to produce his monumental Pittsburgh documentary project. His stolen film was never found, in spite of a search of the Pittsburgh city dump by sanitation workers using shovels and rakes. One can only imagine what was lost to documentary posterity.

While much celebrated in the 40’s and 50’s, Smith’s reputation declined in the 60’s and 70’s with the arrival of a new generation of photographers like Robert Frank, Garry Winogrand and Josef Koudelka. Smith died in Tucson, Arizona in 1978, emaciated and alone. He had $18 in the bank. He had gone out into the early morning streets to search for his lost cat. He fell, hit his head and died of a cerebral hemorrhage at the age of 58.