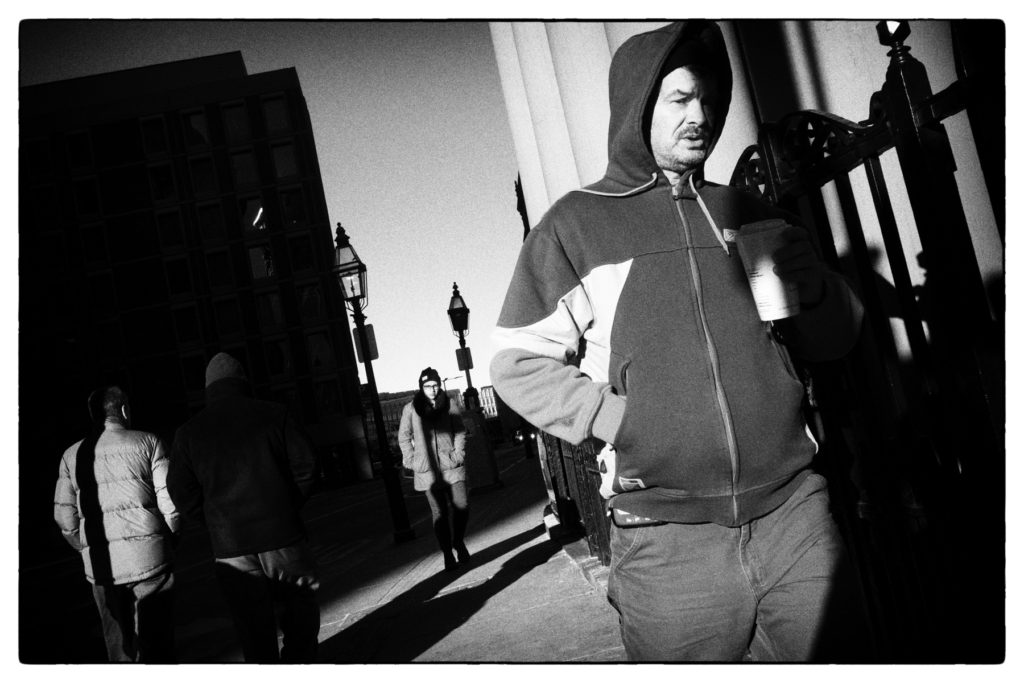

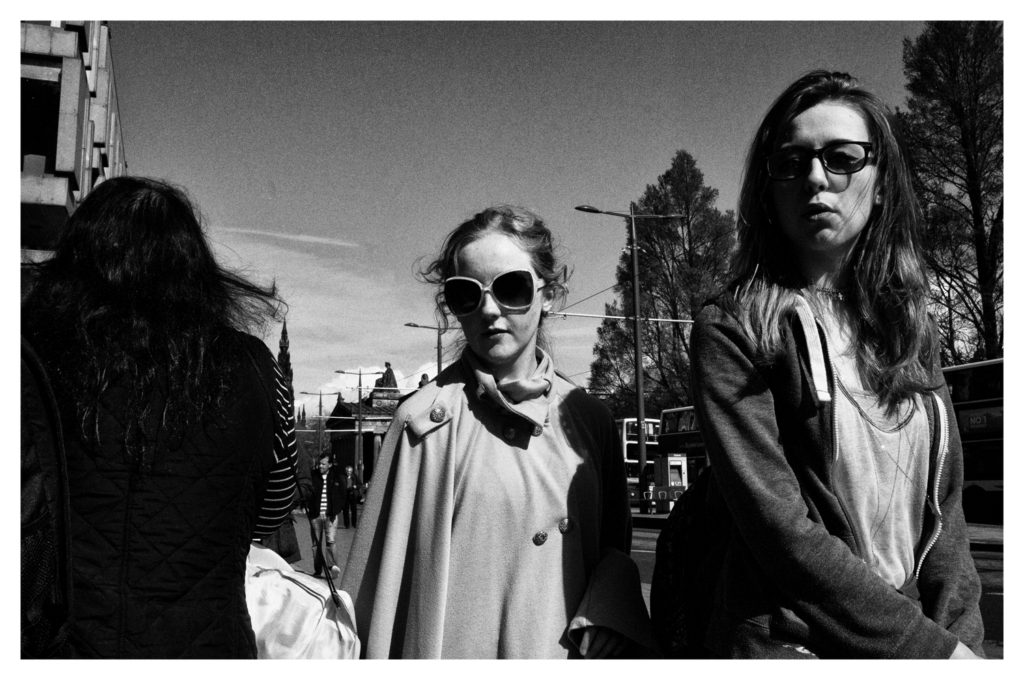

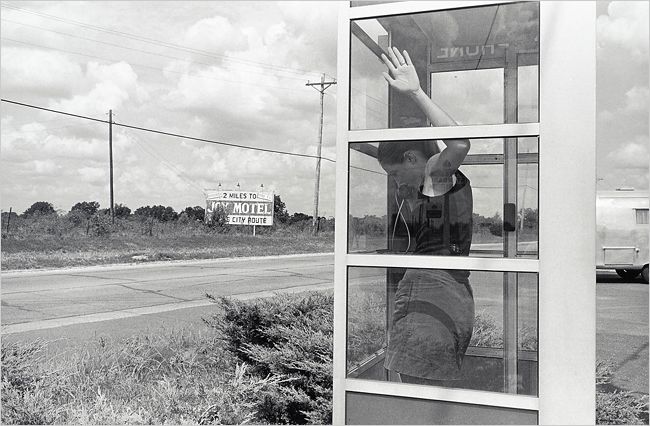

“I’m known for taking pictures very close, and the older I get, the closer I get” – Bruce Gilden

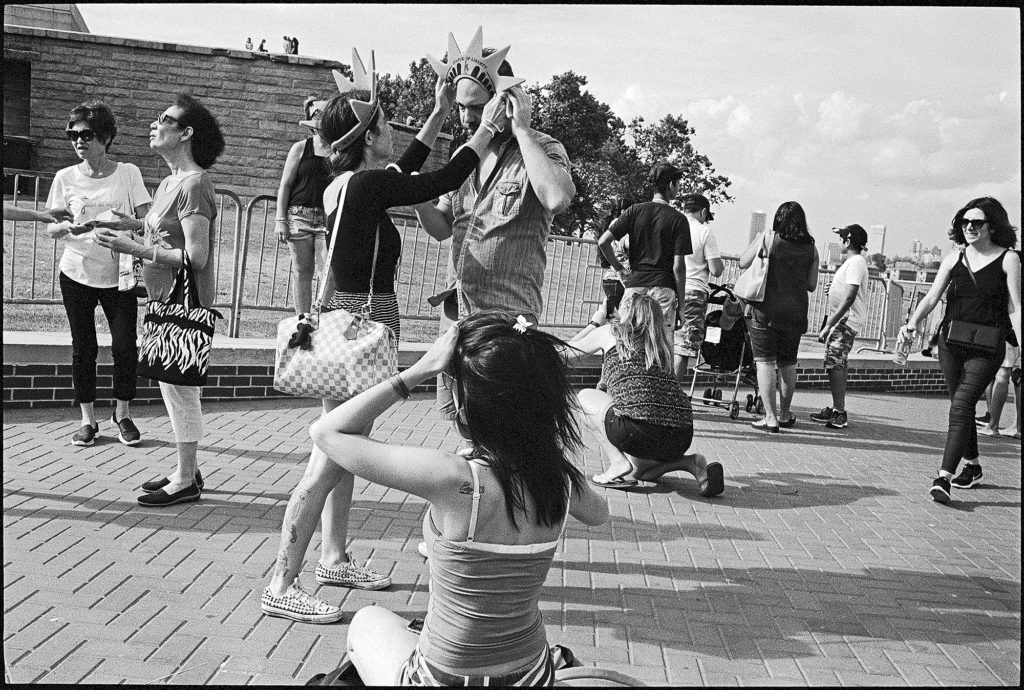

Bruce Gilden is an American “street photographer.” He is best known for his in-your-face flash photos of people walking the streets of New York City. Although he did attend some evening classes at the School of Visual Arts in New York, he’s pretty much self-taught. He has had various books of his work published, has received the European Publishers Award for Photography and is a Guggenheim Fellow. He joined Magnum in 1998. Think about that: he’s a guy who bought a camera, taught himself the craft, and ends up a member of Magnum and a Guggenheim Fellow. It wasn’t about his contacts, or his educational credentials, or the camera he used; it was because he developed his own unique vision.

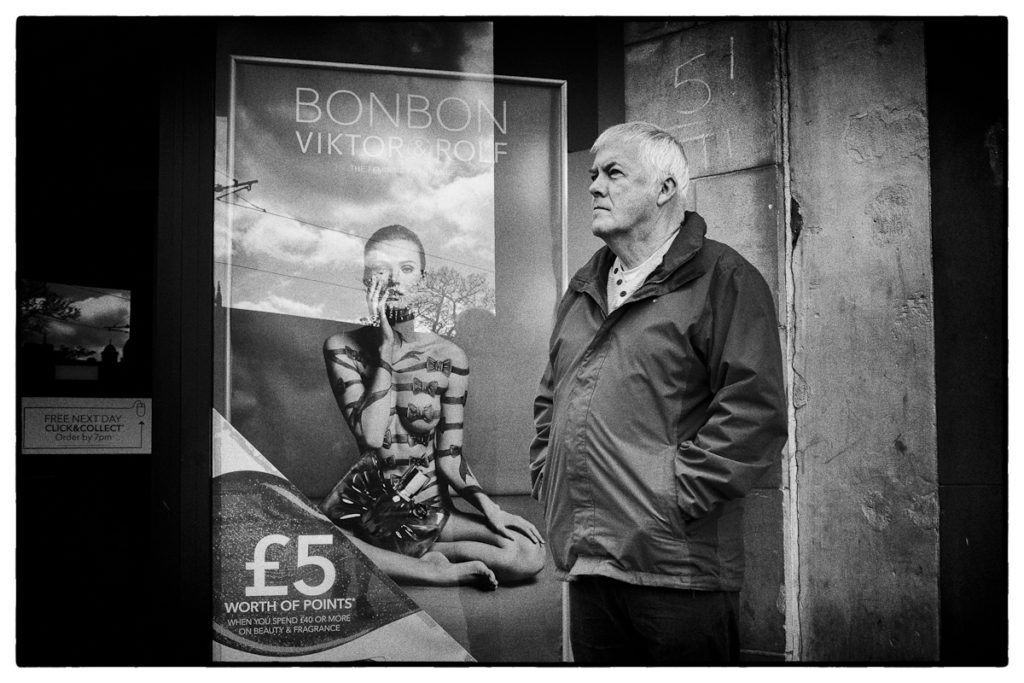

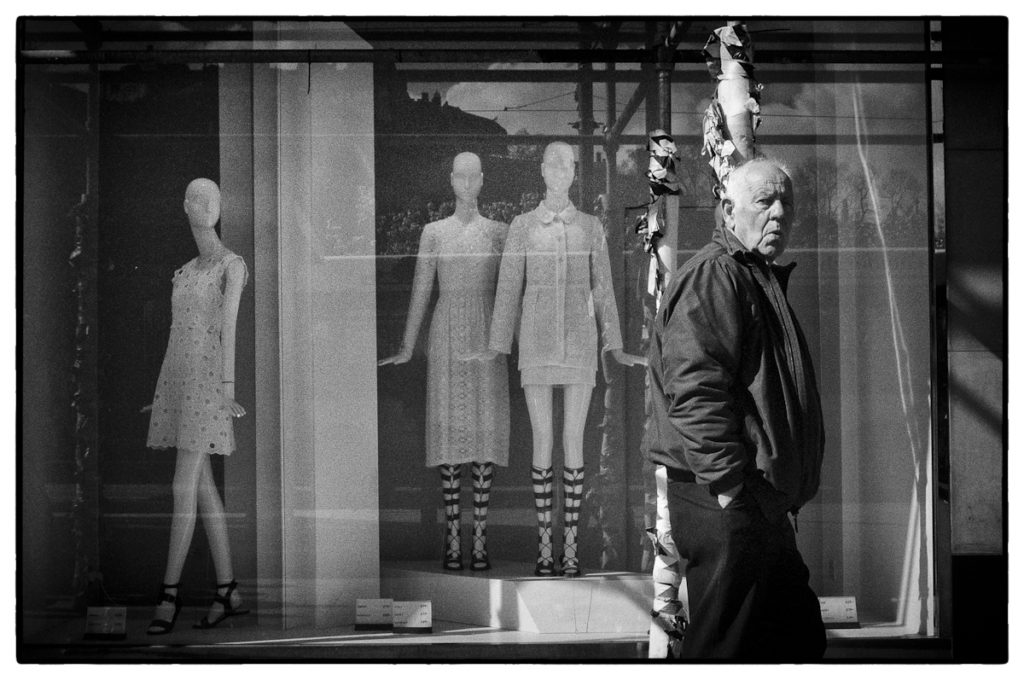

Up until the digital age, he shot in B&W. Recently, Leica gave him a Leica S and he’s been shooting in color since. He’s currently working on a project he calls “Faces”, extreme color close-ups using flash (some of them are illustrating his interview below). While you might consider these photos exploitative of the subjects (and they may be) and ugly and perverse, they’re powerful correctives to the airbrushed faux reality of most visual culture.

I like Gilden. It takes a lot of balls to walk up to someone on the street and push a flash camera in their face. Does it take some special photographic talent? No. But that’s not the point. It takes a certain unified vision. The point is Gilden has created an aesthetic unique to him and hasn’t much deviated from it in 50 years. As such, he’s created a large, coherent body of work. I’ve heard people criticize his work, claiming it gimmicky and artless, something any 8th grader would be capable of. Could your kid have taken these pictures? Yes. But your kid didn’t, and Gilden did, just like it would have been within your kid’s skill set to have painted Jackson Pollock’s Alchemy, 1947. Your kid didn’t, because your kid would have never considered the aesthetic potential inherent in the medium. The genius of Pollock -and Gilden- is having seen the aesthetic others missed.

*************

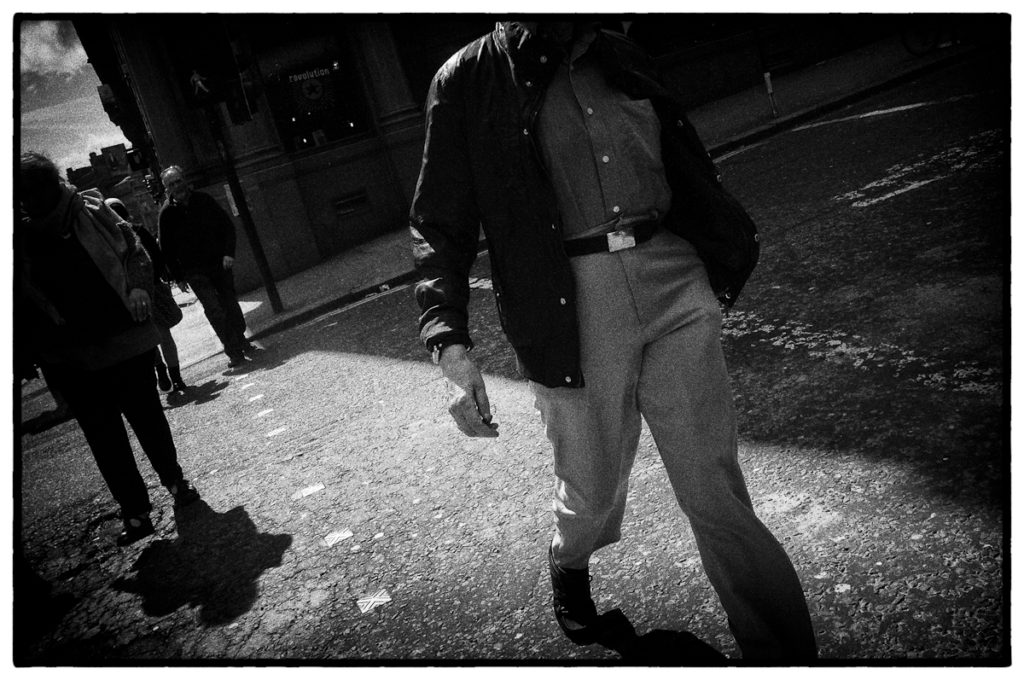

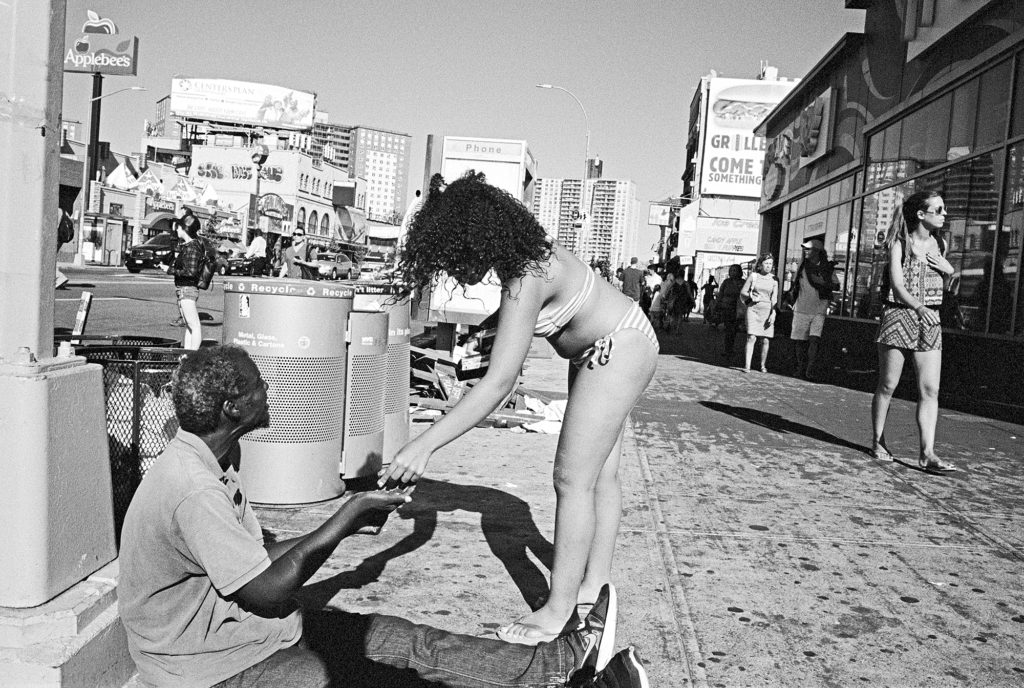

Imagine this Guy Pointing this in Your Face on a NYC Street

This is an interview of Gilden on the occasion of a retrospective of his work exhibited at the International Center of Photography in New York.

ISP You’ve been described as combative, confrontational, as a genius, as “one of the best street photographers currently alive.” How do you feel about these characterizations?

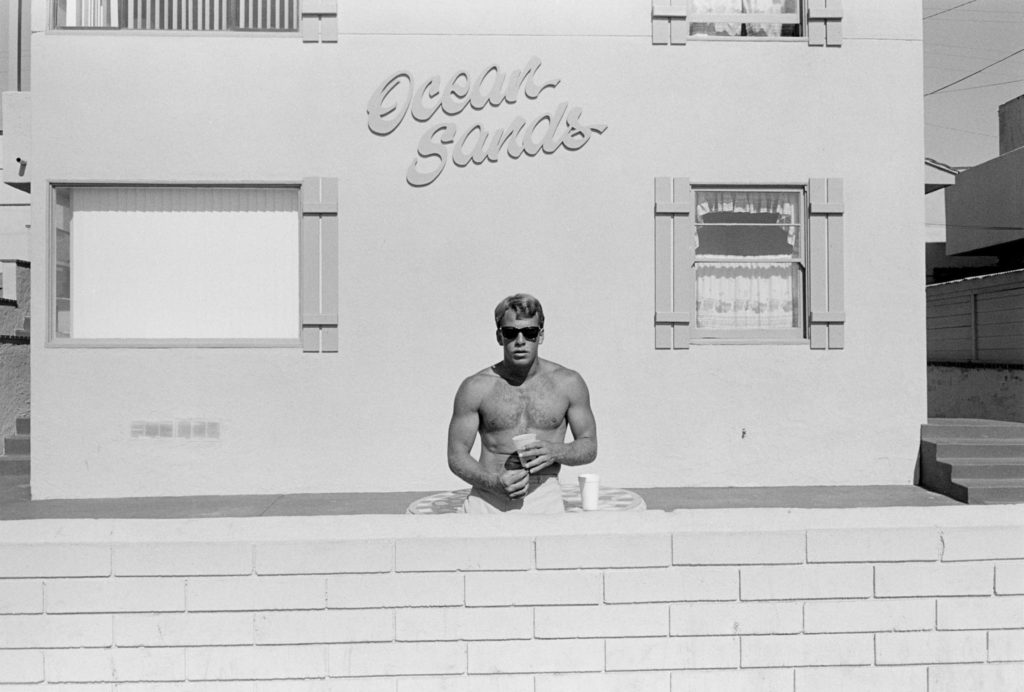

BG A characterization is just like anything else. Some of it may be true, some of it may be false. Look, people don’t know me. I’m basically shy. And I guess you could say I do what I have to do. But I’m pretty good at reading situations. In other words, when you work close with a flash with someone, I have a pretty good bedside manner. If you’re comfortable doing something, run with it. When you’re uncomfortable or doing it for the wrong reasons, then you encounter problems, because people get a sense of your uneasiness. And if people feel you are doing it for commercial purposes, saying, “oh I have to get that lady with the short hair because I’m selling that picture,” it’s completely different than doing it for artistic reasons, for something that’s in your guts and in your soul. So what I do is always in my soul. I don’t take many pictures. Last year I didn’t even work that often because I decided I was really not going to shoot much more in New York City. So all my shooting has been going on outside my hometown of New York. I mean, if someone wanted me to shoot here, if I got a commission here in the city, I could do it. But now I’m starting to go elsewhere around America and see what’s there. The only problem is in America, there’s nobody on the street. I’ve been doing a lot of formal portraits in color.

ISP How do you feel working in color?

BG It’s quite an easy and smooth transition. If you know how to form a picture, you know how to form a picture. It doesn’t matter if it’s in black-and-white or color. I just got back a little over a month ago from the Milwaukee state fair, and I think I did some of the best work I’ve ever done. It’s almost all formal portraits. When I say formal portraits I mean, when I see people at the fair or in Milwaukee I ask them, “can I take a picture of your face?” And I take a picture. So there’s no studio paper. When I say formal, it means I’m asking the person I want to photograph.

ISP They’re preparing for the shot.

BG No, they’re just average people—my kind of people—people I’m interested in. And we take a picture, but I have an idea how I want it to look, to work. They’re very strong. So that’s what I’ve been doing the last year, year and a half. But I’m also doing other things, too. My style might be aggressive, but I always believed in life that the people who stand back are suspect. In life, if you’re going to do something, let the people know you’re doing it. What I mean by that is you have to be somewhat—I won’t use the word “sneaky”—but… if people know you’re taking a picture and it’s supposed to be candid, you won’t get the picture many times. So you have to be smart and shrewd. But I don’t like people who stand half a block away and take a picture, because I find that sneaky.

ISP You’re talking about the “shooting from afar” strategy.

BG Yeah, to me that’s sneaky because you know most people—I take pictures very close—they don’t even realize I’m photographing them many times. But I approach them well. If you’re at ease, you’ll be surprised how other people many times will be put as ease by your demeanor, unless you get the wrong person, which… it happens.

ISP Do you find that happening more now with the change in camera culture and sensitivity to pictures? With the ubiquity of cameras on the street today, the use of images has changed. As such, the response to photographers may be changing. Particularly with the rise of so-called “creep porn,” women especially might become much more aware of and concerned about being candidly photographed by men they don’t know. There are also rising anxieties about terrorism and reconnaissance, surveillance, and even pedophilia that permeate the street. Has this made your subjects more hostile? Are people really more guarded against street photographers? Do you have to work harder to capture an authentic candid picture of someone?

BG It doesn’t change anything for me. I think it has to do with culture itself, and where you work. For example in a rich area like Kensington in London where I worked a lot, you can feel the British class system, so there’s a difference: if you’re rich and cultured, you have almost divine right, and when a plebian comes over to you and takes your picture without asking, more people will get upset than it would happen in a “bad” area. When working in a “bad” area, if you get the wrong people, it has nothing to do with the camera culture. It has to do with culture—period—which I think is more important. The rich, people in Britain, the posh and snotty, they think they own the world, ok, but if you go in a bad area, and if you don’t know how to deal with the people there or you don’t know how to feel them out or joke with them, you’ll have a problem because you’ll get that kind of response: “You’re a stranger you come in my fuckin territory and you take a picture of me!” Some people are good at dealing with that, some aren’t. You carry it in your body language. Again, if you’re comfortable, it will be fine. I used to be a pretty good athlete, so my body language is not stiff, it’s fluid, and if you go at somebody with a fluid body motion, there’s much less chance of a problem. Then I don’t think it matters if a guy is with a woman that he’s not supposed to be with or if he had a bad day, and it doesn’t matter if you’re ten or two feet away.

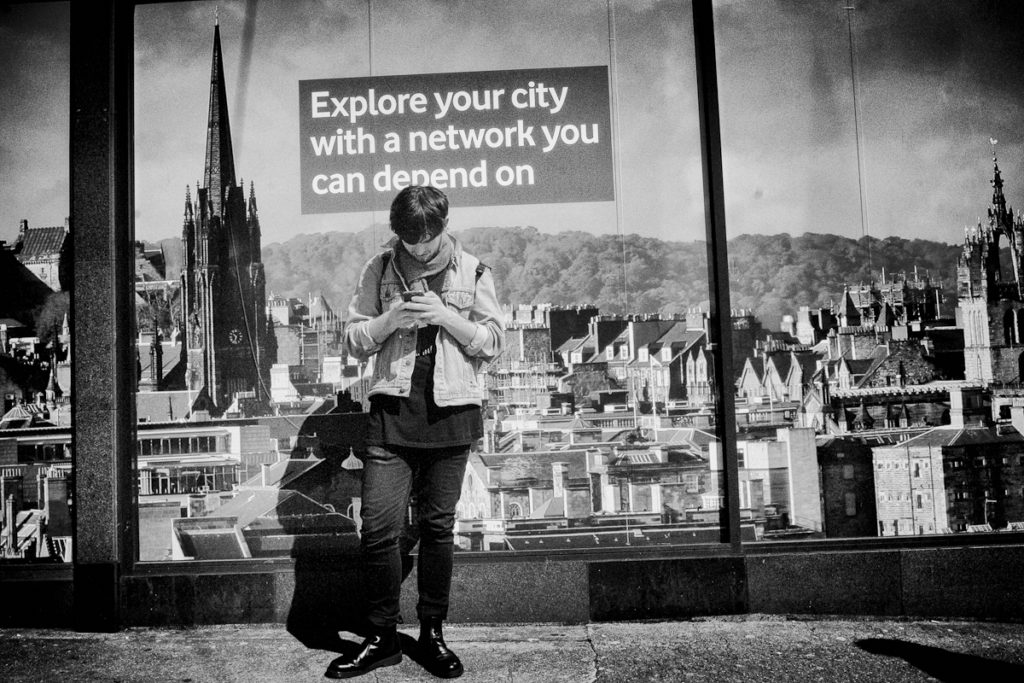

It’s true though that our culture is becoming ruder, and it has nothing to do with cameras. When you walk in the streets of New York or some other large city, people are always on their cell phones. If you collide with someone on the sidewalk, even though they probably walked into you because they’re not paying attention, they’ll turn around and tell you to go fuck yourself. To go back to your question, I don’t feel that way, because I believe that if you look for that problem, you’re going to bring the problem to yourself. It’s like going into a bad area and saying, “uh-oh, the guy’s going to pull a gun on me after I take a picture.” You can’t think like that otherwise you’ll never take a picture. I think that what I’m doing is fine. I’m not hurting anybody. And I’m doing it from my guts. I always feel that the people I photograph are my friends, even though I don’t know them. And they’re also symbols for what I see. It’s not like that person is that person. He or she reminds me of something else. It’s like being in a little movie.

ISP In speaking about films, you’ve mentioned that working with the moving image might be hard for you because you find raising money for projects to be difficult. You’ve also found this to be the case with your photography. How much has it helped you working with Magnum? You joined them in 1998. I think we can all imagine what a highpoint that was.

BG It helps in one way, and it doesn’t help in another way. Magnum helped me to get editorial work, which I had never really done before. But then with all this time spent at doing editorial here and there, I didn’t pursue the art market as much as I should have. Fortunately, I have been working on the Postcards from America project (I travelled to Milwaukee as part of it). Postcards is an ongoing collaborative project in which a loose group of photographers chooses a site that intrigues them and gathers there to play like a visual band. Postcards is a project on its own, but for me, as for many of the photographers involved, it’s also an experimental creative space, and it has enabled me to do very good work recently. In fact, without Postcards from America, I may not have started color. I participated in the first episode where the whole group of photographers stayed in one place. By “group” I mean ten or eleven photographers. We stayed in Rochester. And we had to have 100 pictures in two weeks.

ISP This was the project last year at about this time when you were with ten other Magnum photographers covering the decline of Rochester, NY in the wake of the partial halt in production at Eastman Kodak, which has its headquarters there.

BG Yeah, and I realized—wait a second— I can’t do 100 pictures in two weeks, especially when there’s no one on the street in Rochester! That’s why I started to do the portraits. So in a way it’s good because we’re all competitive and I compete with myself: when other people are working in the same area, you don’t want to look like a schmuck and have no pictures (he laughs). It’s challenging. I borrowed a Leica M9 from Leica and I started to do digital for the first time. I did a little digital in Haiti to photograph the houses the year before because I wanted them in color at night. In Rochester I did a lot of digital work because you’re able to see what your photographs look like right away. This gave me confidence to get to that mark—to that hundred mark. I’m not saying all 100 photographs are good, but it gave me confidence. It was encouraging because you had to get a hundred pictures in a place that you wouldn’t choose to shoot. With all of that combined, I also did black-and-white, and I think the strongest pictures from that take are formal portraits in black-and-white. Doing both color and black-and-white was good,

because there was also a guy who was developing our film. We’d shoot it on Monday, and we’d get it on Tuesday. We could see what we were doing as we’d go along. And then the next place we went to was Miami, where I started to use the Leica S camera, which is the mid-size that I’ve been using since. And everything’s been in color and digital.

ISP And what an interesting departure from the black-and-white candid work that you’ve become so famous for doing.

BG When you’ve been doing something for so many years, it’s always nice to have a change. When I did Foreclosures, no one thought I’d do houses.

ISP Yes, your new book, Foreclosures, is devoid of people. It’s a shocking change in subject matter.

BG I think change is important. How many years can you do the same thing? Look, you never get a perfect picture. But also as you get older things change. My form of photography is very athletic, and I can still do it ok, that’s not a problem. Of course, you can’t bend as low, and you’re not as fast. That’s the concession to age. On the other side, on the positive side, you have more experience. So you know how to get what you want. It’s sort of a balancing act.

The transition has been quite interesting because I’ve worked in Bogotá, I’ve worked in London, I’ve worked in Miami twice, I’ve worked in Milwaukee, I just got back from the Big E Festival in Massachusetts, I’m going to the state fair in Mississippi this month coming up. It’s exciting for me because I’d never worked in color. And I’m doing these intense color photographs of people—my kind of people, people who interest me. I have nice conversations with them. And I don’t like asking people to take photographs, because I’m basically shy and it’s very tiring. But I’m quite good at it. If someone wants to say, “No,” they’re going to say, “No.” But I enjoy it in a certain crazy way. And if you see the pictures, I’d be surprised if you didn’t like them. They are strong.

I can tell you when something’s good of mine; I can tell you when it’s not good. We all care about our work, but I think I’m pretty clear and open. In other words, if I didn’t do well, I can admit it. Not everything that has my signature on it is a wonderful picture.

ISP So there is also a modest side to Bruce Gilden?

BG No, no, look: I worked hard, and I stuck with it. I’m proud of where I am, because I didn’t have a silver spoon in my mouth where I started. I had no inclination to take pictures. I’m not a technician. Having said that, I know what to do to correct things in the field. I’m not ignorant technically. I’m more interested in the person. But the form has to be correct. A good picture for me is well-framed with a strong emotional content. My pictures aren’t loose—my good pictures. Like today, you see a lot of people, and their form isn’t very good. They’re just concerned about getting the image—what they want in the image, that person, or that emotion or something. But the image isn’t formed well. To me that’s not good enough.

ISP Do you think that’s largely a product of digital photography? Some have complained of laziness in framing since the rise of the easily erasable digital image.

BG It’s not just digital. It also may be a product of not learning your craft in a certain way. For example, when I started photography I knew nothing. I didn’t even know when you look in the finder that’s what you supposedly got. But I looked at tons of books and magazines. And I knew what I liked and I knew what I didn’t like. So if I saw a picture I liked, I would see how it was taken, try to find out from the perspective what lens was used. And then you go out and you say, “Oh, that photographer put a person in the front here. That’s pretty good.” So, you use that, but eventually—hopefully—you become yourself. For example, when I started, I was compared to Weegee, Arbus, all these other people. Now I’m just myself, because I take my kind of pictures.

ISP Now other people are compared to you. I’ve seen time and again in print mentions of your name as a point of comparison for someone else’s work.

BG I feel good about that. But everybody has to find their own way eventually. And some are strong enough to do it, and others aren’t. I’m appreciative of that, and it’s funny to read it, but it takes time. Eventually some of those photographers will be referenced as their own. If I’m a step beyond, sometimes someone’s going to be a step beyond me. It’s just the nature of the beast. Records, like in baseball, are made to be broken. If someone’s still shooting in my vein without improving in twenty years, they’re doing something wrong.

ISP You’re saying they have to develop their own eyes. This is something you spend time cultivating in your students. Can you talk to us a bit about Bruce Gilden the teacher? You travel the world for exhibitions, for photography festivals, like the upcoming Miami Street Photography Festival in early December where you will be featured. And you often offer these mentorship opportunities and intensive workshops that are very well-attended.

BG In the workshops, I’m very blunt and honest. And I’ve devised a little system, which I won’t talk about in detail, but it’s quite simple. People who come to the class, some of them, their pictures aren’t very good. And it’s not because of their style: I’m smart enough to see when someone has talent, and I don’t expect them to be little Gildens. I think the most important thing that I can tell them is to photograph something that you’re interested in, and to be yourself. Don’t listen to what anybody says unless you’re smart enough to realize that someone is telling you something that’s constructive—not destructive, because some people don’t want to see other people get ahead.

If someone has strength, I’ll give them assignments that will lead either in a direction to make their pictures stronger or in a direction that they haven’t been shooting. So it opens them up to something else that can help them get where they’re going, that I think they’re a little weak or they’re not paying attention to. If someone isn’t generally doing very good work, I started giving them assignments in my workshop two or three years ago that are usually basic portrait assignments. And I show them how much better their pictures are after they’ve done these portraits, which helps build their confidence. Some of them don’t continue doing portraits, and they don’t have to.

I’m very critical. If someone is good, they’ll know they’re good (he laughs) when they’re finished with my class. I also try not to be overly critical to people who just started photography and also the people who aren’t full-time photographers. If you are new, it’s a bit different than if you’ve been photographing 20 years. I always ask people, “Do you think your pictures are good?” I find that when people come into a workshop thinking they’re really good, they usually aren’t. Then we have to straighten them out. When I ask my students upfront, I get a sense of what needs to be challenged to help them improve. Look, I’m not a god, but I think I’m quite visual. It’s ingrained in my soul. I give a lot of myself. By the end of a workshop, I’m quite exhausted, because I’m open. You can take what I say and think it’s wonderful; or, you might think it’s crap. At least I’m honest. I’m not trying to knock you down just to knock you down. If you do good work, you’ll know it once you’re finished with my workshop.

There’s one guy in my class who has become a very good friend of mine. He’s a bright guy. People looked at his work and said, “Wow! He’s taking pictures like you!” He started to use flash and color. And the pictures are really good. But they’re not mine; they’re his. You can tell when someone’s imitative and when someone’s doing it because that’s who they are. I don’t have a thin skin about that. I think he’s talented. And he doesn’t even do photographs! Now he’s doing more of them. But before he was only taking pictures four times a year! Certain people have the spark, other people don’t. You have to deal with that. But if someone does something good, I tell them how good they are and how good the pictures are. We get into a dialogue. I think I’m pretty good at teaching, but I wouldn’t want to do it too often. I’m not going to be doing too many more workshops.

ISP You do have one coming up in December 2nd – 6th in conjunction with the Miami Street Photography Festival.

BG Yes, in Miami, which will allow me to return to these communities I’ve been photographing down there. This started with the Postcards from America. But I may not be able to continue shooting when I’m in Miami this time, because with the Leica S I have to have an assistant to hold the light for me. It’s very tough. The camera’s heavy. And to get the person the way I want, I couldn’t hold the light at the same time. It’s too much unless I was maybe Hercules. And I’m not.

ISP Is it difficult for you to not have the flash in your hand, to rely on somebody else for the flash?

BG No because we discuss how it has to be done. The difficult thing is if they do the light wrong. Portraits aren’t as difficult as candid street photographs. In the candid street photograph, no matter how much control you have, if you’re combining things in the image, anything can go wrong. The person in the background who you wanted to look left is looking right, for example. But still my portrait assistant in Milwaukee said, “Hey look at this portrait you took!” It’s, I think, about the best one I took on that trip. He said, “Look at the other five pictures that we took till we got to this one. Anyone who says shooting portraits is easy is wrong!” because in the other five pictures… the pictures are terrible. And then I finally got what I wanted. You have to be able to recognize that. You also have to pick how close you want to get. My pictures are close. And it’s not like you can pick anybody. I walked all day around the state fair, and maybe I shot ten people in eight hours. It’s also about them agreeing to have their pictures taken and you deciding how you want their attitudes. Do you want their eyes more open? Do you want them to look directly at the camera? It’s not as simple as it looks. Still when you come from a candid street photography background, it is more simple because you’re working with just the face. It’s different than when you’re working with ten people in a photograph or with someone who doesn’t know you’re taking the picture.

ISP With candid street photos, you often surprise your subjects. That shock of being randomly photographed can cause different reactions in your subjects, particularly when you use a hand-held flash. But in your new work, you don’t have to contend with not knowing how the sitter will react when you take the shot. People who realize they’re being photographed get an opportunity to prepare themselves mentally for the picture.

BG Yeah, but with portraits, people sometimes get too self-conscious. I don’t like smiley pictures. When people realize they’re being photographed, they have all sorts of different reactions. Some are funny. One lady I photographed in London—in Essex, actually—who’s portrait will be in the forthcoming London book, her daughter said, “Mommy, do it! Let him take your picture!” Her daughter was probably in her twenties. The lady got up, and she was so terrified of the camera her eyes bulged out of her head. I didn’t say a word, and she looked more and more intensely. Her daughter tried to put her at ease, but the lady was so stiff! And it actually made for a very interesting picture. So there are a lot of factors involved.

ISP You talk about your subjects as your “characters,” and whether it’s candid street photography or portraiture, there’s a truth of expression—an apparent unguardedness—to the people you choose and the ways you choose to frame them emotionally. This quality is lacking in the more prepared experiences that you’re talking about, like the smiley pictures. It seems to me that you have an aesthetic of sincerity. That honesty is of very high value to you artistically.

BG My honesty, my bluntness, probably comes from my past and my relations with my father—everything I found out (that he was a gangster) and how I found out (in that his tire store, the young Gilden realized suddenly, was devoid of tires). I had a tough emotional childhood. I didn’t realize it at the time, but I see that most people didn’t have my upbringing. At the end of the day, someone could look back at that kind of childhood and say, if they’re not strong, “Look what they took from me, my father and mother, emotionally.”

But they made me what I am, so I guess they gave me strength that I’d never realized until I was older I had. I was always a little different in that I had a lot of energy and was very athletic. I guess I was a little bit wild, but in a controlled sense. There was a lot inside that couldn’t get out.

Photography kept me alive in many ways. So I have that to put into pictures that I think a lot of other people don’t have. I think that gives my pictures strength. If someone else shoots in the same style, but they don’t have a certain background or a certain way that they related to their background, I think they’re not going to do the same kind of picture. That doesn’t mean that they’re not going to do a great picture. It’s just that I do my kind of picture. And other people do their kind of pictures.

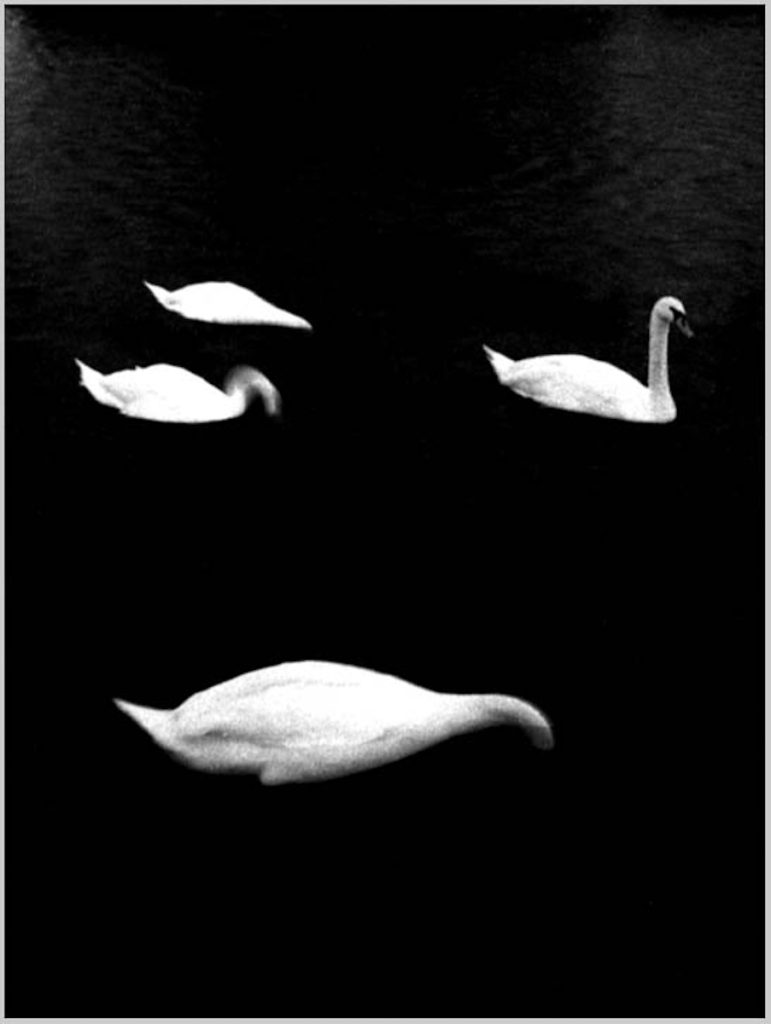

Take street photography: it’s always been the stepchild in the artistic world of photography. But it’s probably the hardest type of pictures to do. That doesn’t mean a street photograph is a good picture and another one isn’t. It depends on how you do it. I’ve seen a lot of bad street photography, just like I’ve seen a lot of bad photography. There’re people that are good, and there’re people that aren’t as good. There was one kid I saw who was very good, and I have a feeling that he has very good potential to be really, really good. You just feel it. He wasn’t in my workshop. He was this young guy who, when I judged the Oskar Barnack Award, he got the Newcomer Prize—a Polish guy, Piotr Zbierski. I think that Zbierski has a talent that can’t be taught. He has it in his soul. The pictures of course are a little dark, they were black-and-white. I mean, dark in what he photographed, almost like a fairytale.

ISP Like a Grimm’s fairy tale?

BG Yeah, and they’re good! Most people don’t have it. He had it, and he was very young, 23 or 24. But I don’t know how he got to it.

ISP You mention his work is dark. Your work, too, can be dark in that you often focus on what people describe as “the dark side” of people. Your photographs gravitate towards extreme and criminal subcultures. You’ve been quoted as saying you like “bad guys” in reference to your continual return to this subject matter.

BG My father was a tough guy, so the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree.

ISP And while you are drawn to this character, you don’t romanticize it. Gangster culture, the Yakuza, the Russian mob, gangsters in the UK and Australia: you don’t romanticize them in the way that you shoot them whereas a lot of portrayals of gangster have this sheen of cool.

BG Yeah, because they didn’t grow up with it. I learned a certain type of respect, that you don’t ask questions. I often get along with people in that culture because I know never to ask a question. I don’t want to know, because if you know, you could be responsible for putting someone else at risk. And it makes sense to me because that’s how I grew up. Look, to me, (gangsters are) just like anybody else. In some cases they can be better because at least you know who they are and what they are. So other people, like for example a corrupt policeman or a priest who’s a pedophile, you go to them for security and then they violate that. I won’t call the gangster a “bad guy,” I’ll call him a “tough guy.” Look, people take what they can; they’re not going to take liberties with tough guys, because they’re tough. And they will take it with someone else. But the thing is, I look at tough guys and see that they’re human beings. And I like them, I generally like them. When I was in Australia with Mick Gatto, I had a great time! He was such a gentleman and a wonderful guy. Sometimes I have admiration for tough guys—some of them. But I’ve met some I don’t like also. Those who abuse their tough-guy-ness, who try to test you, you have to stay away from them. It’s like the regular population: some people are good, some people aren’t. And they do what they do.

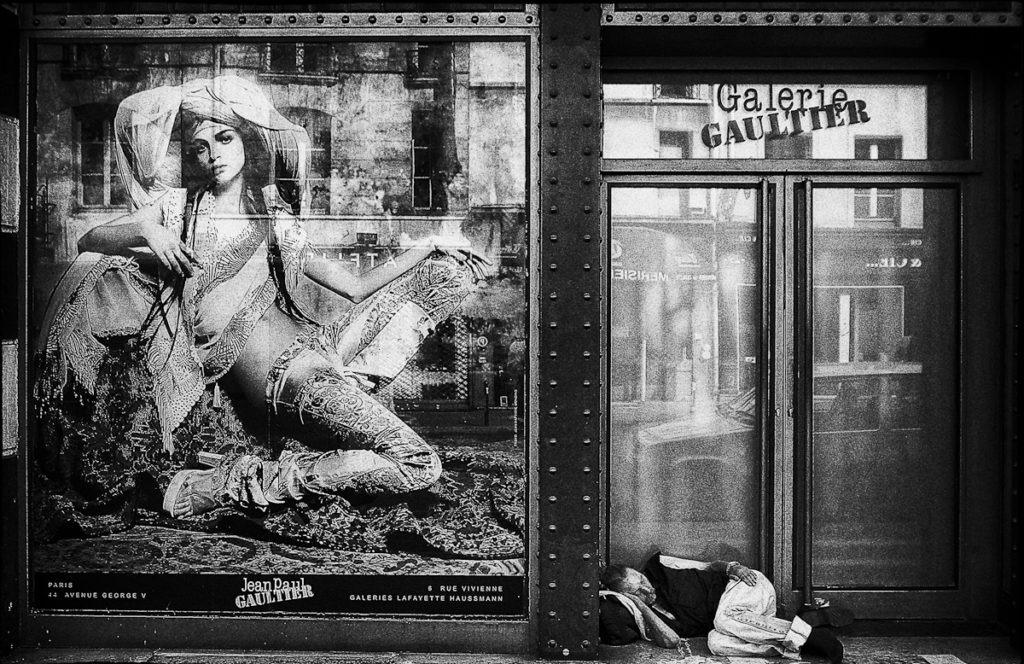

ISP I see this aspect of your work not only as an engagement with your father, but also something that coheres with this critique of the economic system that I think your work mounts. Crime and criminals disrupt business-as-usual. And it seems like your work, in the most obvious way with Foreclosures, but also in your traditional street photography, poses real challenges to the way we see people as a culture, which is largely a function of economics. Your work looks where others don’t. Last year, as you’ve mentioned, at about this time you were covering the decline of Rochester, NY after Eastman Kodak cut 50,000 jobs. You’ve been

working on Foreclosures since 2008, documenting the fallout of the subprime mortgage lending crisis. You have been criticized for your use of surprise close-up flash photography in the city streets. You focus on people you describe as “the left behind” in your work. There is a truth, as we’ve mentioned, in this work often lacking in the prepared appearances of those who are ready to be photographed. That truth in itself seems to make a statement about the lack of sincerity in the visual world of ubiquitous advertising. To me, this is major source of connection in your work. Do you think your work has a central focus of economic critique?

BG I like people who tell the truth. I hate politicians.

ISP You recently photographed Anthony Weiner.

BG I photographed all of them—all the New York City mayoral candidates for the New York Times Magazine—and I liked all of them on a one-to-one basis. Some more than others. But they’re politicians.

But to return to the question you raise, I can’t talk as much about Foreclosures as I could have before, because when I was preparing for it I read about 20-25 books. But that was a few years ago. It was legalized thievery, what the government did (the subprime mortgage lending crisis and its aftermath). They repealed the Glass-Steagall Act. There were no regulations on a trillion dollar industry. And there was this fantasy that everybody should own a home. It was disgusting. So no matter what I or any other people can do, we can’t come up to the heights of that. Then we bail out the banks with taxpayer money. And then you read that this quarter Chase Manhattan made outlandish profits. I mean, come on now! Please! I’m not a fool. They say, “fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me.” I come to the topic from that perspective. And like I said, the people I photograph are my friends.

I have always identified with the underdog. I’m not coming to this like some art director who plays in the street, then goes on to do something else. I come from the street. I’ve always been in the street. It’s something that attracts me. I didn’t have your average upbringing. My father didn’t exactly model good behavior or offer moral guidance. I had nothing to live up to and nothing I wanted to be. I didn’t have to go into my father’s business, which I used to drive a scrap metal truck for. But I didn’t have this background like I’m John Lewis, III or something. I was loose that way. I always felt that I was an underdog, an outsider. For me, you also have a certain freedom when you’re left behind in that way, because you’re not enchained or imprisoned. But I don’t have to make up a whole intellectual dialogue about what I do. I do what I feel to do… when I have the money to do it. And I’m pleased with that, with what I do. And if you’re comfortable you have a chance of doing it well.

And I also always identify with poorer people. But I’m not a bleeding-heart liberal, the kind that say, “Oh, I think she had a very bad upbringing, and that’s why she knifed you in the back.” No one’s going to knife me in the back if I can help it. I had a tough upbringing, and I survived. So I expect you to be able to survive.

I’m a realist. As a realist, you know the world’s a terrible place for many people. I don’t think it’s getting any better. The have-nots are going to be getting further and further behind. So many people are left behind by our political and economic system. And that’s the project of my Guggenheim: The Left Behind. When I was in Russia, I went 70km outside of Ykaterinaburg and I wondered, “What do these people do?” We live in New York City. If you don’t travel to see these things about the world, you may not know that people in certain countries and places are really left behind. And it’s getting worse. It’s not getting better. It’s a terrible thing. I feel better that I’m 66 and not 25. I feel bad for my daughter. Look at the ozone! Look at what’s happening with the weather now! And who’s doing it? So many people, and all just for money.

ISP I recently read a quotation from environmentalist Derrick Jensen that said basically that if

aliens came to Earth, systematically deforested the planet, killed 90% of life in the sea, we’d declare war on them. But for some reason when corporations do that for profit, it’s generally accepted.

BG Yeah, that’s a great statement! There are people who are helping the planet, people who are advancing medical research, people who are doing things that are helping humanity. And I find… well, I’m not big on the non-profit groups, though. I spent a lot of time in Haiti. And the one I really like is Médecins sans frontières. Most of the others just know how to waste money.

ISP I’m interested to hear what you think about the Occupy movement.

BG Occupy Wall Street? I went down to lower Manhattan for the protests, and I think you had the wrong people for the right job, at least here in New York. Half the people down there were high on drugs, running around, and playing flutes. They looked like they’d just rubbed their chests on the ground for the last three weeks and didn’t take a bath. It’s not that I’m against that either, it’s just that it was starting to go somewhere. I met a great lady in Las Vegas who runs it out there. She’s great. The Occupy movement elsewhere has been more successful. And I agree with them and with the premise. But the Manhattan protests were a mess. The problem is that a lot of the people in the tents and stuff are people who are… losers, for fault of a better term. They seem more interested in hanging out than getting things done. If you want real economic reform, you have to defeat these guys at their own game.

I believe in Machiavellian theory. Absolute power corrupts absolutely. Take that rebel who’s fighting against the government, put him in power, and he’s going to become the very thing he was once fighting against. When you get millions of dollars in front of you, how many people aren’t going to take it? I do prefer people who are—even if I don’t like their politics—who say what they’re going to do, even if I can’t stand it, like Bush (W.). I couldn’t stand him, but at least he said he would do this, and he did it. I don’t like Obama.

ISP In that you feel he’s insincere where you found Bush to be more genuine.

BG I feel like he’s full of shit. Look, he said he cares about the middle class and lower class. But even progressives don’t like him. Harry Belafonte can’t stand him either. And he’s always been a progressive who supported MLK, the Civil Rights Movement, all progressive agendas. He hates Obama. And I do too, because the guy walks with the swagger of someone who knows the street, which he doesn’t. He says one thing but does another in policy, too. He said we’re not going to dig for oil in America; we are. We’re going to get out of Afghanistan; and, we’re still there. In the foreclosure crisis, which I can talk about a little because of the research I did for my new book, he decided to keep Timothy Geithner as Treasury Secretary and Ben Bernake as Federal Reserve Chairman, who were responsible for repealing the Glass-Steagall Act (an act that had imposed financial regulation in the US, and that, once repealed, contributed to the economic crisis and its resulting financial devastation). And Geithner, whether he worked on Wall Street or not, has been working for Wall Street all along. He’s part of the reason that everything went so bad for the world economy! So if you want change, you’ve got other people to put in charge of the economy. He could have pulled in Volcker, who’s a smart, good guy in that field. No, I don’t like that guy (Obama). I can’t look at him. You know, I have my opinions. Those others guys are terrible, too. But he’s no different. He wouldn’t have gotten to be President if he hadn’t been pushed by somebody. I think he made backroom deals.

ISP Do you have any suggestions on how to get money out of politics?

BG Well, maybe you can’t. But to me the decision to keep Bernake and Geithner really sticks, because they were complicit in the whole financial collapse around the subprime mortgage lending crisis. So it makes no sense to ask them to be responsible for changing the problems of the economic system when they had a hand in creating those very problems themselves. How do you justify keeping people who support all that Clinton and Bush (W.) did? This all started with Clinton saying that everybody should own a home. But everybody should own a home who can afford it. Anyway, let’s get back to the subject.

ISP It is in a sense very much the subject of Foreclosures.

BG I’ll talk about my cat (he laughs). I have three cats! They’re very nice. Three Russian Blues. They’re sweet as sugar. They calm me. I pet them all the time, I talk to them. They’re my friends. Why don’t we move to the next question.

ISP After the discussion we’ve just had, this may be a jarring transition. But what do you think is the future for street photography? Here we have been talking about imminent environmental or financial collapse, so it seems like a strange question now.

BG I don’t think like that. I see what’s in front of me. I think the scary thing, not only for street photography but for the world, is that everybody’s becoming the same. The cities are more homogenous now, the shops. If you go, god knows where, you see a Starbucks. People wear the same clothes. The world is smaller. They all listen to the same music. People more and more are losing their individuality. And I think ultimately in a hundred, 200, 300 years, everybody’s going to look the same and be the same and maybe act the same. I’m stretching that now to make a point. Whereas I look for the differences, there’re people who look for the similarities. So it makes sense that there would be a change in what pictures look like. But I don’t know.

In 1888, Kodak first made it possible for a lot of people to take pictures. Now we have the digital age and the iPhone. Everybody’s taking pictures. Maybe more people are taking them now than then, but Kodak made it affordable then. Almost everybody can take pictures now. So it must have been quite cataclysmic when that first happened. The common man could all of a sudden take pictures. You didn’t have to pay to go to a studio photographer to take a portrait.

ISP But now the camera phones that you mention make choices for you. They make visual choices for you.

BG I haven’t seen that myself, but I’d heard that. And it follows along what I was saying: there’s going to be less and less individuality. If you look at the movies now, so many movies are about the effects; whereas, years ago, all the movies I liked were about relationships, emotion, love. If you listen to the music from years ago, doowop and so on, it’s about boy meets girl, boy loves girl, girl drops boy, boy drops girl. It was human! We are becoming less and less human. And one thing I don’t like: we’ve become so politically correct that people are afraid to do anything because—gasp!—it’s not the right thing to be seen to do. Yet they’ll do worse things, and they’ll be accepting of worse things.

So, to answer your question, I don’t know. But I think street photography will go on until there’s no more street. It depends what you mean by street photography, too. I said to a magazine once that in street photography you could smell the street, feel the dirt by looking at the picture. You’re seeing less and less work like that. Look at most photography today, and even if it’s good, you still can’t tell who took the picture. The average picture could have been taken by 500 people; whereas, years ago, if you saw a Cartier-Bresson, you knew it was a Cartier-Bresson. You see a Winogrand, you know it’s a Winogrand. You see an Arbus, you know it’s Arbus. A Weegee’s a Weegee. The best usually have a recognizable style, a personality.

Also, a lot of street photography is confrontational, unflinching. But people don’t always like to be turned upside down. To be confronted. To think, to feel. It’s more challenging to the viewer,

some people don’t like that. But I feel it’s important as an artist to show work that challenges. If we don’t show something just because it’s difficult subject matter, who’s going to know its there? If things need changing but they aren’t shown, they’ll never be changed. I’m not saying you’re going to make a difference anyway. Look at all the war photographers, and still we have war.

ISP What’s next for Bruce Gilden?

BG I’m working on my Guggenheim project, The Left Behind. I got a commission in the Midlands in the UK to do a similar project. A photopoche book, one of those pocket-sized books from France, comes out this November. The London book is out this November, too. It was commissioned by the Archive of Modern Conflict and is formally titled A Complete Examination of Middlesex. But ultimately, what’s going on in my life now and in the future is my family. My daughter Nina just turned 21 and is graduating from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston this year. My wife, Sophie, speaks better English than I do even though she’s French. She was a journalist for Libération in Paris and a radio host on France Inter. I have a good wife, I can’t complain. She’s intelligent, elegant, attractive. And we love each other. Twenty-two years. Some would say it’s impossible to stay with me 22 years, but she did it!