Category Archives: Uncategorized

Digital Panatomic-X: The Sigma SD Quattro Foveon

The Utterly Weird, but Compellingly Fascinating Sigma SD Quattro

I’ve always been a lover of quirky, neglected and/or unfairly maligned cameras. Hence, my allegiance to the Leica M5 and the Ricoh GXR, two of my favorite cameras, both of which were critical and popular disappointments. I also own, and love, the Sigma SD Quattro. Sigma says its 20MP APS-C sensor produces a resolution “equivalent” to 39MP. In reality, it’s way better than that. My experience is, when shot at ISO100, it easily resolves fine details much better than the 36MP D800E, which was, at the time of the Quattro’s introduction, the Mack Daddy of high resolution full-frame DSLRs, and I suspect it can hold its own against the current crop of 60MP mirrorless. All of this out of a 20MP APS-C sensor.

The SD Quattro’s Foveon* sensor is what makes the SD Quattro unique and allows it to punch so high above its weight. Traditional high resolution digital sensors employ a Bayer filter sensor where red, green and blue photosensors are positioned at discrete locations. The Bayer filter then ‘interpolates’ them (i.e. makes an educated guess about what, for example, red would look like in a position where there is no red photosensor) to produce a full color image. The Foveon sensor ‘stacks’ the red, green and blue photosensors on top of each other at the same location ( in other words, there’s a red, green and blue pixel at every position) producing significantly sharper files than a Bayer filter sensor at same resolution. Frankly, it’s not even close. ‘Why’ it would do so, from a technical standpoint, is beyond my expertise. Just know that it does. If sharp resolution files are your thing, a Foveon sensor is what you want.

It also produces really nice, tonally rich B&W files that remind me of the look of Panatomic-X, and does so right out of the camera with exceptional jpeg files. While I’m hesitant to admit it, given my love of the M9 CCD Monchrom’s output, I think the Quattro is the better B&W camera. It’s that good.

*************

ISO 200 B&W Conversion in Silver Efex

Build quality is excellent. This is no cheap, plastic-y camera. Made from a magnesium alloy, fit and finish is really nice. Buttons and dials feel robust. Ergonomics are surprisingly intuitive, much more so than digital Leica’s and contemporary DSLR’s and mirrorless offered by Canon/Nikon et al.

In spite of all the above, the Sigma SD Quattro (and the Quattro H) are most decidedly not for everyone. They aren’t a camera you’re going to grab going out the door if you’ve got other less complicated options. They’re cumbersome in any situation in involving live action – people photography, ‘street photography’ , sports. They’re bulky and super slow in operation. If you’re shooting RAW, don’t even think about shooting them at any ISO above 400; in fact, it’s advisable to not shoot at anything other than its native sensor sensitivity of 100 ISO… or 200 ISO in a pinch. (Shooting jpegs is another story, which I’ll address shortly).

But man, when you use it as it was meant to be used – 100 ISO steadily handheld in sunlight, or on a tripod – the results are remarkable. It gives you DNG files that allow almost endless manipulation to get whatever look you’re after. They are particularly good for B&W conversions. They are incredibly sharp even at large magnifications, and their Foveon-ish* sensor produces a noticeable something that even current 60MP sensors don’t. Viewing the output of my M9 Monochrom (itself capable of really sharp, clean fines at lower ISO way better than you’d expect from an 18MP sensor) with an out-of-camera JPEG from the Quattro makes it clear just how good 1) Quattro jpegs are and 2) the Foveon sensor is in B&W.

Out of Camera jpeg from the Quattro using the 4:5 Aspect Ratio In Camera Crop

A DNG RAW file from the M9 Monochrom – Processed in Lightroom

The ability to shoot DNG RAW files is a major upgrade from Sigma’s previous Foveon cameras, which shot a proprietary RAW version that required conversion in clunky, bug-ridden Sigma software (although the latest version Sigma Photo 6.8 is pretty good). In 2004 Adobe created the DNG file format to replace the various proprietary Raw (.RAW) formats of differing digital cameras. The goal was to provide a standardized file format that could be processed on any computer system or viewer without special proprietary software. DNG files are supported in software such as Adobe Lightroom, Photoshop, Camera Raw.

With the Quattro, you also have the ability to avoid shooting RAW format entirely: the jpeg processing engine is really good, which allows you some ability to shoot at higher ISO’s – expose properly and you can shoot jpegs in color up to ISO 400, and black and white to ISO 800. Yes there is some degradation as you increase ISO, but because of the clarity of the Foveon pixels you can still print and display at very large sizes. One upside of shooting jpeg is the reduced file size; the DNG files out of the Quattro are enormous and take a lot of processing power to work with. Of course, the downside is you’re stuck with the rendering the jpeg engine gives you. Suffice it to say that the Quattro is the only camera I feel comfortable shooting in jpeg mode.

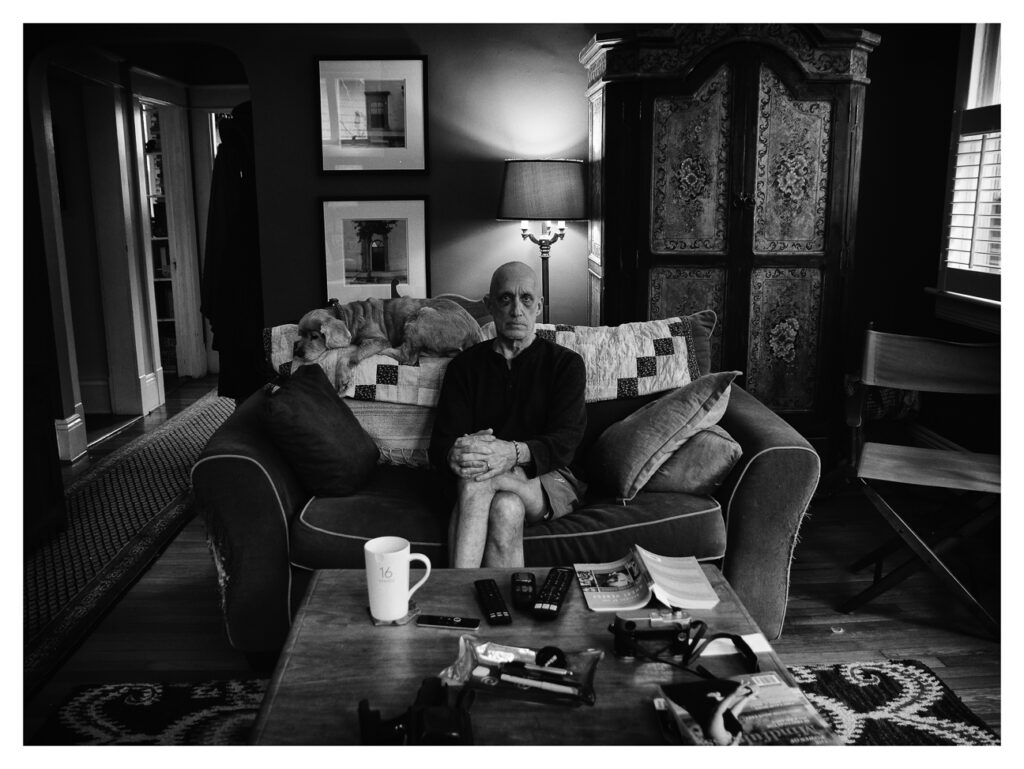

Out of Camera jpeg From the SD Quattro – Me Looking Like Uncle Festor

*************

And then there’s the issue of lens choice. The Quattro employs the Sigma SA mount, a mount Sigma used for all its SLR and mirrorless cameras until they discontinued it in 2018. As such, you’re limited to pre-2018 Sigma optics (of which there are plenty and most of which are really good, the trade off being most are also quite large). I’m currently using the Sigma DC 17-50 2.8 EX HSM which is solidly built and sharp at all apertures. If you need a ‘standard’ prime, the excellent Sigma 30mm 1.4 ART lens fits the bill nicely (that’s it on the photo that leads off the piece). Just realize that you’re going to be limited to already existing Sigma optics.

Sigma discontinued the camera in 2018. They’ve replaced it with the fp, which uses a full-frame Bayer sensor. This means that the Quattro is probably going to be the last in the line of commercially produced Foveon-sensored cameras, as Sigma wholly owns the Foveon patent. I applaud Sigma for doing something different; their Foveon cameras, from the original 4MP DP series through the Merrills and ending with the Quattro are all fascinating departures from the norm. IMO, their strengths – super sharp, super detailed RAW files – transcend their obvious limitations. It’s a shame the marketplace killed it. I suspect Foveons, and the Quattro in particular, are eventually going to achieve cult status, with in-the-box examples bringing exorbitant prices. Ten years maybe?

UPDATE: Maybe not…..

July 2022: Sigma CEO Says More Foveons Coming. Yay!

Should you buy one? Yes. Full Stop. These things are currently bargains used. Buy one – or an equally weird Merrill or DP Quattro – and use it. The question is which one. I’ve owned most iterations – the 4MP DP2x, the DP2 Merrill and the Quattro. I loved the pocket-sized ‘4MP’ DP2x with its fixed 24mm 2.8 that produced beautiful color files looking like those from a camera with 5 times its resolution but, alas, the lower pixel count precluded you from printing big. The Merrill’s produce stunning output, but unfortunately tether you to Sigma’s RAW processor, which is a nightmare to work with. Were I to choose one my preference would be the Quattro, as it offers the ability to shoot DNG files you can post-process in Photoshop or Lightroom without recourse to the dedicated Sigma software and it allows use of the entire range of Sigma SA optics. It also shoots really good jpegs, which the Merrill did not. I haven’t used the DP Quattro series, which Sigma offered after the Merrill and before the SD, but I assume the image quality is on par with the SD. As I understand it, the DP series is the SD with fixed lenses (and a very weird design).

The Quattro H, a slightly larger sensor than the Quattro (1.3 crop as opposed to the 1.5 crop of the base Quattro) commands a premium over the APS-C base Quattro, but I don’t see much functional distinction between the two. Given the price difference, I’d stick with the base APS-C model. Current prices are all over the map, as you can see from the Ebay offerings below. Having watched past auctions, $800 should get you a lightly used Quattro body and either the 30mm 1.4 Art lens, or my choice, the 17-50DC EX with IS. What you’ll get is an APS-C camera that easily out-resolves the latest Leica M, isn’t going to ever become “obsolete,” and will keep your interest permanently. Certainly, if you aspire to landscape photography, take things slow and use a tripod, this is the camera for you. Plus, this thing just oozes cache; pull it out and start pointing it around and every DSLR toting Ansel Adams and Leica M HCB wannabe is going to be secretly envious. Thorsten [von] Overgaard will be completely flummoxed. Try doing that for $800 in Leica land.

*************

Get the PG-41 Power Grip and Extra Batteries. You’re Going to Need Them.

We talk of Leica being the one camera company offering digital cameras that hearken back to – and retain vestigial features of – film era cameras and their operation. I’d suggest that the Sigma SD Quattro does the same. Operation is reminiscent of a MF film camera loaded with a high resolution low ISO film. Think of a Hasselblad loaded with Panatomic-X.

The Quattro requires you to slow down and think about what you’re doing. Its slow start up and interminable write times give you no choice. Its energy hungry sensor eats batteries, so, much like film, you’re best to make every shot count. There’s no doing it wrong and having the camera’s automation correct you. But do it right and work around the camera’s inherent limitations and the results can be stunning. It rewards pre-visualization and proper technique with subtle color detail or wonderfully detailed, tonally rich B&W files. Those who’ve worked with MF film cameras will feel right at home.

Mine. Yes it’s Big. So is a Hasselblad 501CM with 80mm Planar.

*The X3 Quattro sensor used in the SQ Quattro is slightly different than the original Foveon sensor. The blue photosensor layer at top has 4 times the high resolution of the red and green photosensor layers underneath it are of lower (1/4th) resolution.

Another Pointless Photo Comparison

One from the M240. One from the M9M

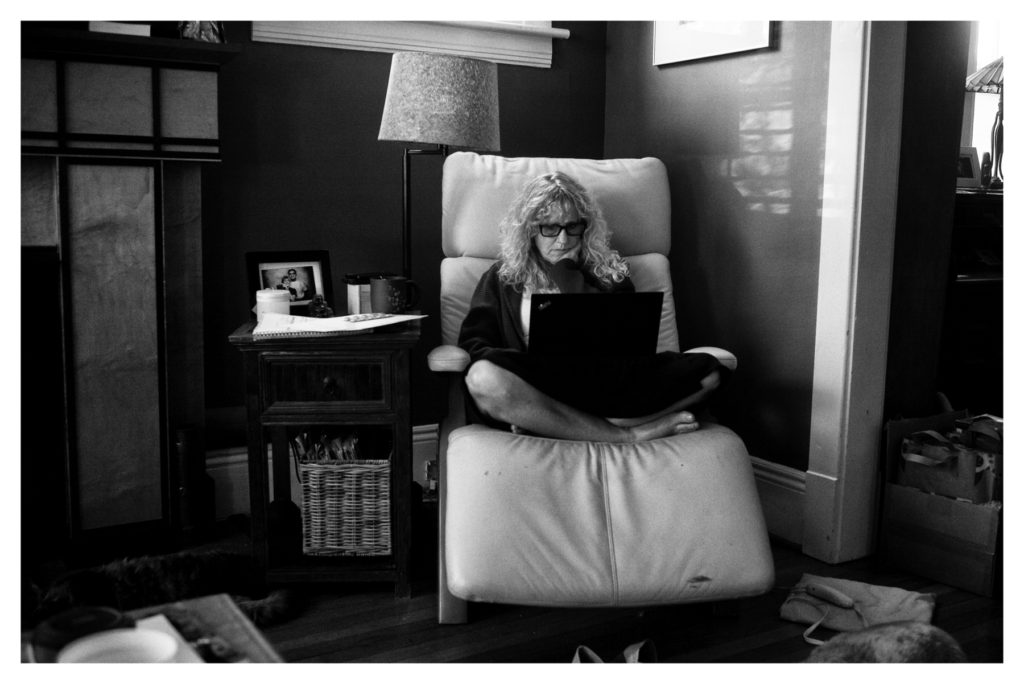

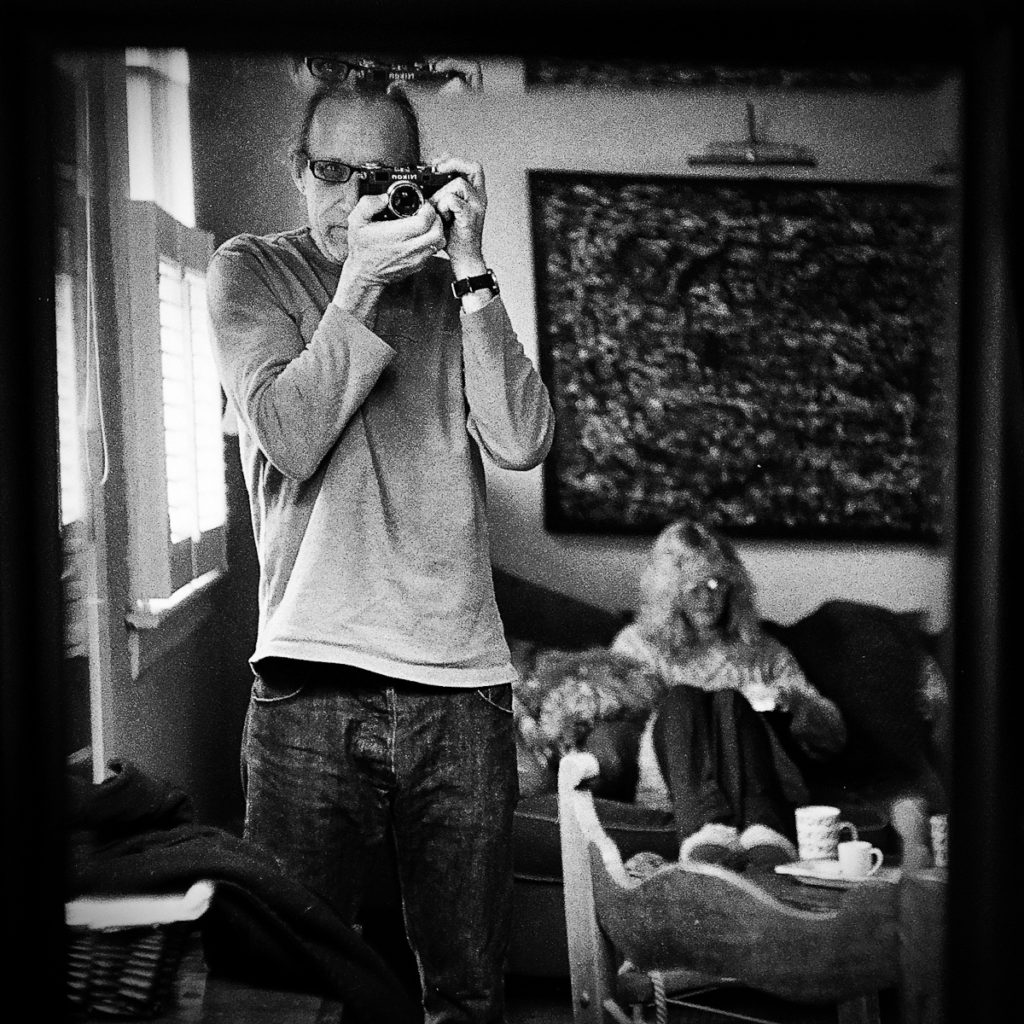

I’ve always told myself that if I started posting pictures of my wife/kids/pets to fill up space I’d shut Leicaphilia down and call it a day. It’s inevitable, at some stage, you run out of things to stay, no matter how much you’ve said in the past. I suspect I’m getting dangerously close to that time, given I’m now reduced to posting pictures of my wife. I could do worse, I suppose. My wife is easy on the eyes. In any event, the best I can promise you for the time being are some fairly thoughtless comparisons like the output of the M9M versus the M240. I really do like both cameras, but have developed a distinct preference for the M9M since I shoot exclusively in B&W. Native B&W output seems one less unnecessary step, and I do think the M240 suffers in comparison to the M9M’s sharpness and tonal output. Plus its a cool camera, period, the first digital M that really feels like an M4.

What you see above is essentially the same photo, taken with the same lens (VC 35mm 2.5 LTM) and parameters (ISO 2000, f4, 1/60) – one with the M240, one the M9M – both unedited except run through Silver Efex at identical settings. I see a difference. You can right-click on them to view them in a new window.

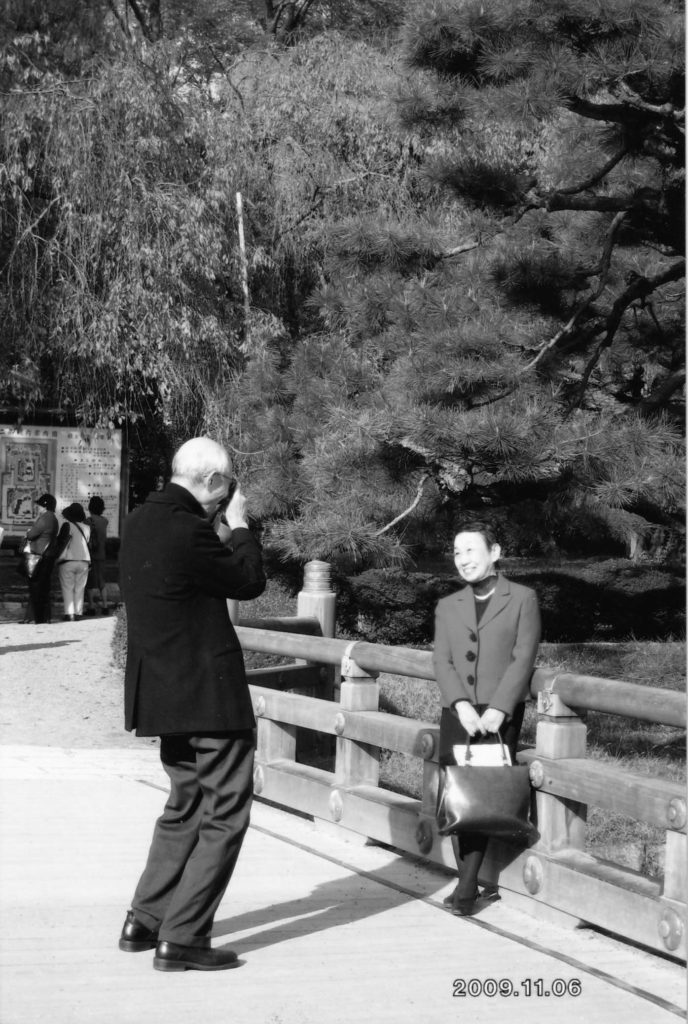

*************

I really enjoy publishing this blog. The amount of feedback I get from readers is really fulfilling, and people have been incredibly kind in wishing me well since I’ve been sick. I can genuinely say that I’ve made friends here, which is something the old, cynical version of me would have scoffed at; but it’s true. Lot’s of good people have shared lots of good things with me, both via the comments section and behind the scenes. I appreciate all of it. I’ve especially enjoyed publishing work that readers have submitted- Shuya Ohno’s homage to his father being a recent example of a beautiful piece of work that probably wouldn’t have found a wider audience if not for the blog.

Unfortunately, I’m completely devoid of inspiration to be posting interesting or thought provoking content myself. I’m battling a serious case of cancer that had laid me out. I went from someone who literally never had an illness, someone who acted and felt a good 20 years younger than I was, someone who could ride 100 miles on a bike at an 18 mph pace, or row a 2:04/500m pace for and hour, to a frail man who needs his wife hold his hand to walk around the block. It’s been a humbling experience. What’s helped tremendously is the wife….and all the well-wishes I’ve received from so many of you. Thank you.

Plus, I’ve chosen to stay enrolled in my graduate history program, which I’ve been lucky enough to do given COVID has precluded having to travel to Boston to attend classes in person. So I’ve been able to do a lot of work online, which, of course, takes up much of my free time, although it’s a pale substitute for walking through Harvard Yard on a beautiful Spring day. When I complain, as I’m want to do, my wife rightfully reminds me this is a first-world problem at best. Plus there’s my professional career. All of which is to say that it’s improbable you’re going to be getting much from me in the way of interesting content for a bit. Expect more useless photo comparisons until such time as I’m up and on my feet and at least walking the neighborhood without having to hold my wife’s hand. A ride around the block on my bike probably is going to have to wait for the time being.

Memento Mori: Ohno Tsuneya, Oct 9, 1937 – Dec 23, 2017

By Shuya Ohno

[Editor’s Note: This was sent to me by reader Shuya Ohno as a beautifully designed PDF presentation. Unfortunately, I’m not sophisticated enough to publish the PDF as received, so I’ve reformatted it for publication. It’s a loving tribute from a son to a father and how that father passed his love of photography – and a Leica M3 – to his son.]

My father – Ohno Tsuneya – was born into a peaceful small town in the hilly countryside of Saitama prefecture, a few hours by train from Tokyo. His hometown, Chichibu, nestled among small mountains provided an ideal playground for a young mind to explore fields of wildflowers filled with insects, forests reverberating with cicadas all summer, and brooks and streams with nymphs, tadpoles, crayfish, and minnows. In town, he gathered with other schoolchildren on Sundays and spent his pocket change on candy so he could listen to the local kamishibai busker tell stories with his hand-painted pictures depicting fantastical illustrations of ghouls and heroes.

Like any boy during that time, he played baseball – that American import that’s also quintessentially Japanese. Like me, my father was slight in build, tall and lanky. Not athletic but loved to hike, ski, and explore. When the fever of war swept across the country, my father like all the young boys his age were indoctrinated at school to defend the motherland, and with their spindly arms taught to hold and wield bamboo poles as spears to poke at straw effigies of enemy soldiers.

As the youngest of four siblings, my father had freedom to play. His father, a local politician, was a man of airs and appetites, a connoisseur who raised renowned hunting dogs that he had imported from Scotland. All the filial duties and expectations to succeed fell on my uncle, my father’s elder brother who my father no doubt worshiped.

WWII and the devastation of the country left Japan with per capita income less than that of India at the time. Late in the war, Tokyo in a single firebombing raid saw over 100,000 civilians killed, over a million homeless. Food was scarce. My mother’s mother sold off kimonos to buy rice, and sewed the rice into blankets to smuggle from the countryside to Tokyo for family. My father’s mother had to smuggle rice from more rural areas back to Chichibu. After the war, Japan threw itself into the long arduous task of rebuilding the country and society. My grandfather Ohno Tetsu died in 1950, during the American occupation of Japan. He was 46 years old.

*************

My uncle Ohno Mitsuya sailed to the US to study journalism at the University of San Francisco. He never returned. Suffering from Marfan’s syndrome, he died presumably of a burst aortic aneurysm. He was only 23 years old. My father was still a teenager – and was now the only man of the house.

He came out to Tokyo to study at 9 years old, and eventually went on to study medicine at Jikei Medical University – the school he would later return to as a researcher and professor. He met my mother, Taniguchi Makiko when he was a student, bicycling across town to see her.

My mother was born on the first day of summer in 1940 in Tokyo, though her family hailed proudly from Kagoshima, the southern holdout of the last of the samurai. Her father Taniguchi Eizo served in the capital as an attorney for the City of Tokyo. During the war, her family fled to the countryside near Hiroshima after their house in Tokyo was firebombed. Eizo continued to work in Tokyo. On August 6th, 1945 my mother was 5 years old, playing when she and her mother saw a flash in the sky in the distance – it was the first atomic explosion and the end of the war. Eizo did his legal duty and served as a defense attorney during the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal.

Like my father’ father, Ohno Tetsu, my mother’s father Taniguchi Eizo died in 1950. He was 56 years old.

My father was 13, my mother was 10 years old when they lost their fathers. My mother’s mother, Emi, died after struggling with severe depression for eight years. My parents came of age without having a father in their lives.

*************

My father loved photography – the art, the activity, the ritual, the tools. One of the last times he and I shared an outing was a brisk February Sunday in 2004, a day before my 38th birthday. We spent the afternoon at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography to see a retrospective of Tanuma Takeyoshi.The exhibit spanned 60 years of Tanuma’s career, beginning with images of post-War children in Tokyo from 1949 that he took as a young apprenticing photojournalist.

In 1956, the Family of Man exhibition came to Tokyo. Tanuma was inspired by this exhibition and went to see it again and again. So did my father. The exhibition is still regarded as a grand undertaking, 503 photographs from 68 countries – its magnitude matched only by its own hubris and that of its curator, the photographer Edward Steichen.

However naïve it may seem today, the driving aspirations and ethos of the exhibit, to capture and encompass humanity in its multitudes as a single connected family, was situated firmly in the liberal ideology of its time, reflected in the contemporaneously articulated charter of the United Nations:

We the peoples of the United Nations determined to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war…to reaffirm faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person, in the equal rights of men and women and of nations large and small, and… to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom.

*************

The post-war Japanese intellectual of the late-Twentieth Century was an amalgam of times and cultures. Adorned with a black beret or a bucket hat, tucked into a turtleneck, the aficionado of culture and the cool connoisseur of consumer goods practiced as an amateur naturalist, a hobbyist polymath, and a citizen of the world. Simultaneously Modern and Romantic, the intellectual eccentric saw himself as hero, like a Sherlock Holmes – a Victorian avatar that still stubbornly abides in Japan.

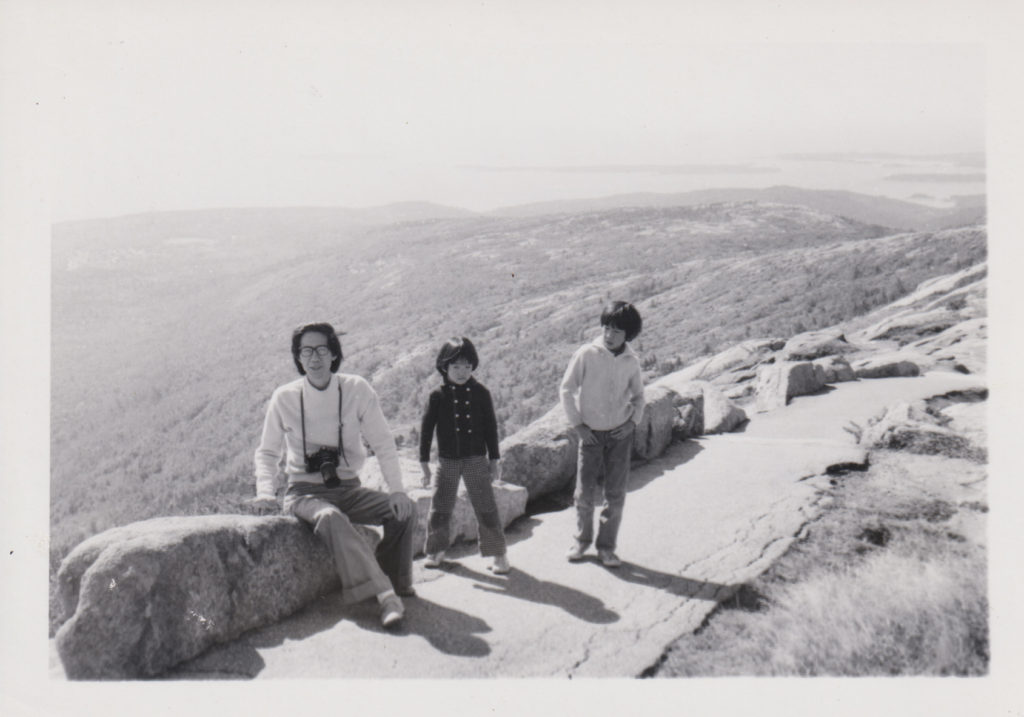

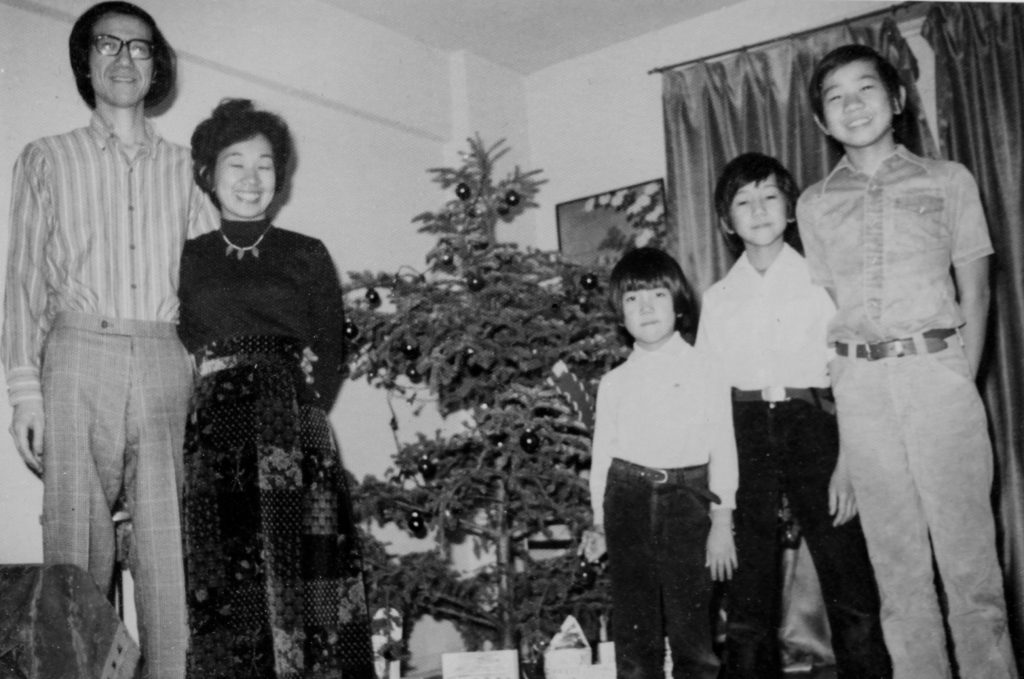

It is not surprising then that my father left us in the United States and returned to Japan. He had brought us, my mother and my brothers, Shinya and Michiyuki to the US when I was 6 years old. My parents remained a married couple – we were still a family – just separated by 13 time zones and 6,740 miles. He left when I was 14. I had worshiped him until then.

Throughout my high school days, I felt his absence, and filled it with rage. I was angry at myself for feeling angry toward my father – I felt like I was desecrating some sacred filial code. I drove my mother crazy, at times to tears. She deserved none of it. It took me into adulthood until I stopped following in his footsteps and abandoned science, until I worked feverishly making art, and then making social justice change that I felt relieved of my anger, forgiving my father and accepting and understanding him. He never saw it as abandonment, just a temporary necessity dictated by his work ethic. My mother eventually joined him after Michi graduated from Rutgers. Michi was perhaps the most American of us for having grown up in the US since he was 3 years old, but he too went to settle back in Tokyo.

*************

I inherited my father’s 1956 Leica M3 (#831611). It’s not that he bequeathed it to me. I claimed it a couple of days after he passed away. I like to believe he would have set it aside for me – but perhaps he meant to sell it. I didn’t know this M3 existed until I was rummaging through his cabinet of classic cameras, divvying up the collection between my brothers and myself. It was not a camera I had ever seen him use. He used a Nikormat while we all lived in the US. He gave that camera to my brother Shinya. My father used a black Leica M6 after that. But I knew what the M3 meant to him. We had years ago discussed its lineage and its reputation as the pinnacle of craft and industrialization, the greatest camera of the 20th century.

Industrialization and the availability of the easy point and shoot 35mm camera became a turning point for the modern world. Susan Sontag in her seminal essay, “Photography,” first published in the New York Review of Books in 1973 presaged my father’s relationship to his camera.

“The very activity of taking pictures is soothing,” she wrote, “and assuages general feelings of disorientation that are likely to be exacerbated by travel.” For my family, it was not travel but immigration in 1972 – jarring and alienating. Language proficiency, or rather its lack, always kept my father a little apart from interactions, a little behind in conversations. I could always see his desire to drop the bon mot, the jokes and puns he had in his head, if only he had mastery over English the way he had over Japanese. Instead, he had his camera. Sontag continued, “Most tourists feel compelled to put the camera between themselves and whatever is remarkable that they encounter.” It is a fine instrument for capturing and collecting moments but also a tool for defense.

Her essay is still incisive, perhaps more so with the advent of the cellphone. “People robbed of their past seem to make the most fervent picture-takers, at home and abroad. Everyone who lives in an industrialized society is obliged gradually to give up the past, but in certain countries, such as the United States and Japan, the break with the past has been particularly traumatic.” Migration only exacerbates this break.

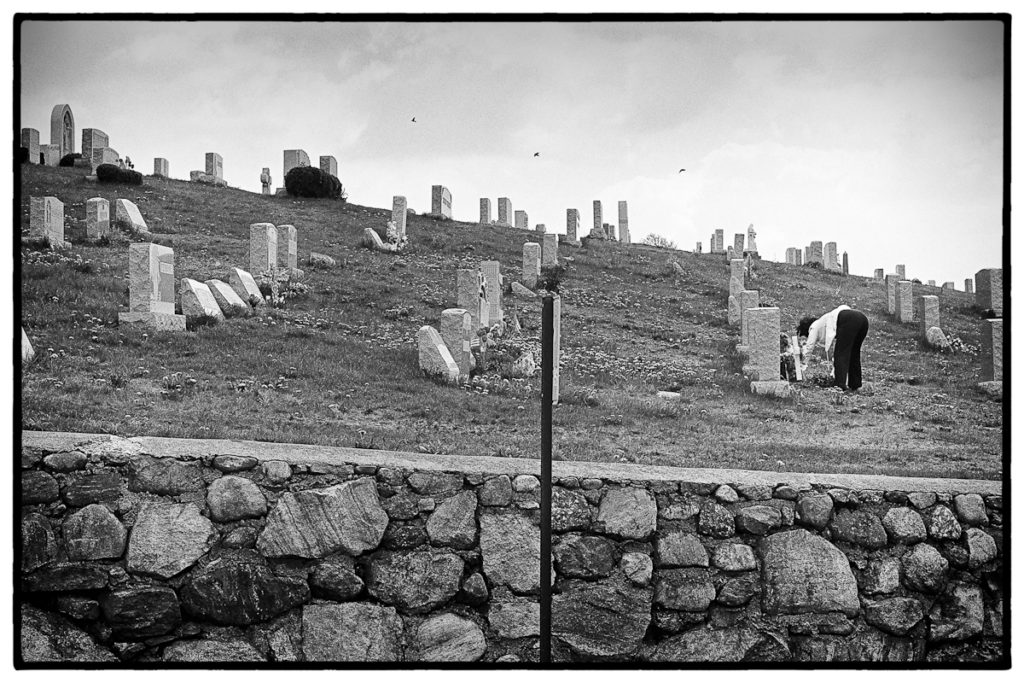

For the last two years of his life, my father was bed-ridden in the hospital. He was intubated and then given a tracheotomy, taking his voice. By the end, he lost his desire to communicate, left his thick glasses by the bed and no longer cared if he could see.

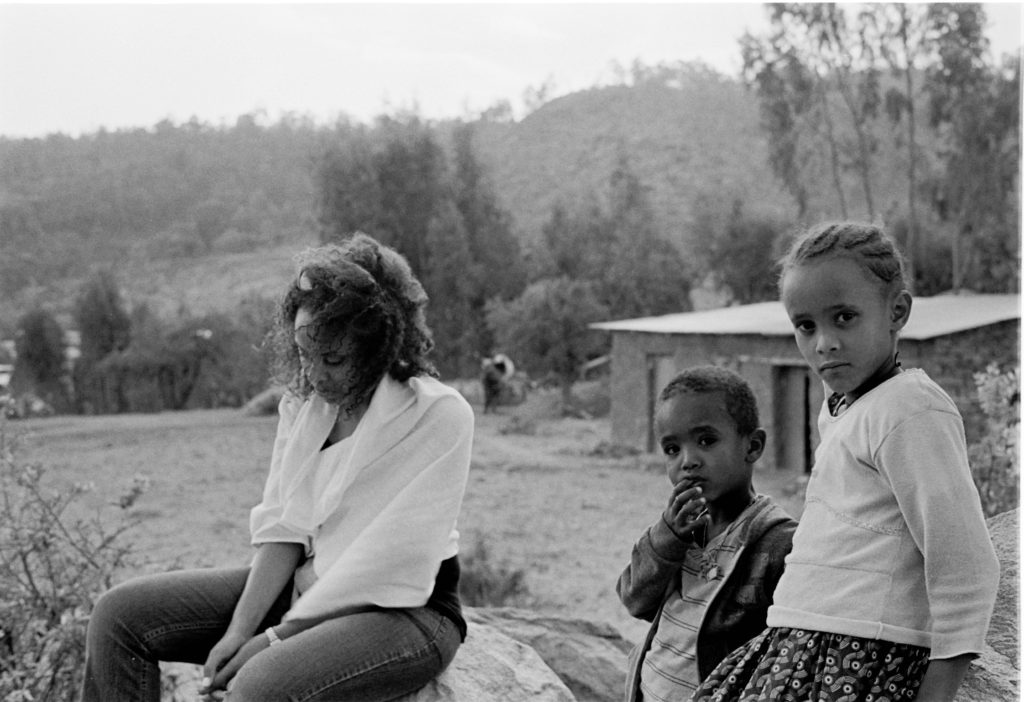

I inherited from my father, not only his camera, but also his adulation for what he glimpsed in that Family of Man exhibit – a vision of humanity suffused with dignity and love for all people, an exaltation of the everyday, the celebration of the common person, and the democratization of art

Now I strive to take photographs that express my love for the world. And every time I pick up the M3, every time I press the shutter, it is a continuing conversation with my father. The viewfinder of this old camera is his eyes, as I ask him, “Do you see? Do you see?”

*************

“All photographs are memento mori. To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.” – Susan Sontag.

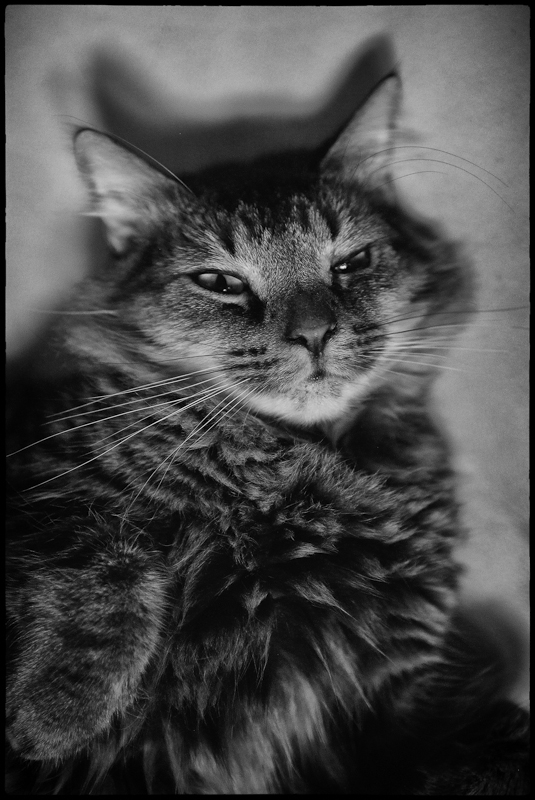

Buddy

Buddy, Sucking Up to My Brother-In-Law

If you’ve been reading me for any length of time, you’ll know I have a dog. Buddy. You’ll probably have picked up on the fact that I Love Buddy. A lot. Me and Buddy are a pair; where I go he goes.

I actually have two dogs, but I’m partial to Buddy (don’t worry – the other one gets my wife’s undivided attention). I’ve had him, now, for 8 years. My wife, visiting a local pound about another animal, was introduced to him by a kindly pound worker who had taken him to heart. Apparently, he’d been there since a pup and no one had the heart to euthanize him even though no one seemed to want him. Donna called me while driving home and told me about him. What the hell, I said, go get him and bring him home. So she did. It’s remarkable how such ‘off-the-cuff’ decisions can change your life. I love this boy in a way hard to explain.

Buddy is what I refer to as “a piece of work,” pure personality and joie de vivre. This past weekend he got banned from the dog park by my home for “improper behavior” i.e. he insists on humping the other dogs. His predilection for humping had heretofore been overlooked – tolerated – because in all other respects he’s a real sweetheart, just as pleasant and good-natured as they come. Unfortunately, he started humping puppies at the park. Apparently, humping puppies is crossing the line. He’s been banned.

*************

He doesn’t seem to be taking his banishment personally, which is to be expected. As I’m writing this, my wife has found him under the dining room table eating some gingerbread cookies last seen on a plate on the table. He’s remarkably nonchalant about the whole thing, feigning ignorance as to how the cookies might have made their way from the plate to the floor. Undoubtedly, in a few minutes, he’ll be happily nestled at my feet with a shoe in his mouth, his way of reminding me it’s time to go walk.

I’ve never had the first problem with him. As I said, he’s super sweet. He makes me smile. He’s just a sweet, goofy critter with a huge heart and unshakable loyalty to me. And he’s funny. I’m not sure how to explain his ‘sense of humor,’ as if a dog could have a sense of humor – but he does. He’s most definitely a funny guy. Look at the photo below, and tell me that guy doesn’t have a wicked sense of humor. Admittedly, I’m anthropomorphizing him. So what.

FOCA: The French Leica

The coupled rangefinder interchangeable lens Foca cameras, of French design and manufacture, spanned a 20-year period from 1945 until the middle of the 1960s

The manufacturer of the Foca, ‘Optique et Prescision de Levalois’ “OPL”, produced French military and naval optical equipment. Optique et Precision de Levallois Co. and its production of FOCA cameras, were the result of the ambitious project of Duke Armand de Gramont. After participating in the creation of the Institut d’Optique Theorique et Appliquee, de Gramont decided to compete with Leica and Contax by producing a 35mm rangefinder. He called his camera FOCA, a take-off of the German LEICA, but also to refer to its principal characteristic, the focal plane shutter. The camera factory was based at Chateaudun, Eure-et-Loire. The first Foca camera was designed in 1938, but the Second World War prevented its release until 1946. The first Foca models were named “PF” (for petit format, “small format”) and distinguished by the number of stars – PF1, PF2, PF3. They used a focal plane shutter and screw-mounted interchangeable lenses.

The “PF1” (one star), later named “Standard”, was the basic version without rangefinder. The PF2 incorporated a rangefinder/viewfinder, a full 8 years before Leitz did so with its M3. After 1949, the company developed a bayonet mount version, called “Universel”, with a series of lenses all coupled to the rangefinder.

OPL made its own lenses under the brand “Oplar” and derivatives (“Oplarex”, “Oplex”). The “Standard” was offered with alternative ‘normal’ lenses : a 50mm f3.5 Oplar, f2.8 Oplar or a 50mm f1.9 Oplarex. The f1.9 lenses are of the six-element gauss symmetrical design. The f2.8 lenses were 5 element, the 3.5 a 4 element Tessor. 28, 35, 90 and 135 Oplars were also produced for the Standard (see below).

Today, Foca’s are much sought after by collectors of French ‘classic’ equipment and quality Leica copies.

| * (PF1) | 16,001-21,200 | 1946-1947 | No rangefinder. Screwmount lens. |

| * (PF1 Standard) | 1948-1962 | No rangefinder. Screwmount lens. Star engraved. | |

| ** (PF2) | 10,001-15,999 | 1945.10 – 1946 | First model released. Rangefinder coupled screwmount lens. Shutter 1/20 to 1/500. |

| ** (PF2bis) | 1947-1957 | Shutter speed to 1/1000. Rangefinder coupled screwmount lens. Stars are engraved. | |

| *** | 1947-1951 1957- | Hi / Lo shutter speed dials (separate). The early 1947-51 are very few in number. |

Happy New Year

2020 couldn’t leave soon enough. COVID, a Cancer diagnosis, an attempted Fascist coup by an insane American ‘President.’ 1/3rd of Americans believe prominent Democratic politicians are running a cannibalistic pedophilic sex ring out of a pizzeria in Washington, DC. Seriously. Personally, I despair where it’s all going from here. Think of Weimar Republic Germany for an apt analogy.

As for me, I’m rededicating myself to shooting the remaining 2000 feet of B&W film I’ve got stuck in a deep freezer. Maybe I’ll get through it before my eventual demise. I keep on selling excess cameras, divesting myself of ‘unnecessary’ inventory, only to buy back twice as much as I’ve sold. My current new favorites: a black paint Canon V with black paint 50mm 1.8 and 35mm 1.8, a beautiful Leotax F with f2 Topcor 50mm, a Nikon S3. ( While I have my M5, film-era Leicas have simply become too expensive – $3000 for a garden variety M6? Right.) Something about those old mechanical jewels fascinates me. I often find myself walking around the house with one or the other in my hands. Yup, I’ve become that guy.

As for all the photos, God only knows. Bodies of work that include time lived in Paris and Amsterdam and NYC, extended visits to Oxford, Cuba, Morocco, Eastern Europe, Spain, Italy, Delta Mississippi, rural NC. A six week trip up the Yangtze River with a Leica M4 and a 35mm lens, passport stolen in the middle of Chinese nowhere (try traveling in China without a passport), sleeping in a Buddhist monastery overlooking the river west of Wuhan for a week, dinner in a Communist Party’s members-only Tiananmen Square restaurant exchanging cigarettes and tall tales with Chinese apparatchiks. All those photos will go in the trash once I’m gone. Why not?

*************

It’s the family photos that I go back to. The other stuff is vanity. I made a conscious decision, years ago, not to have kids, so the family photos probably get trashed too. In confronting my mortality, I’m struck with the simple fact that what I’ve dedicated a life to, the product of a 50 year obsession, really has no value to anyone but me.

But that’s OK. Its meaning is for me.

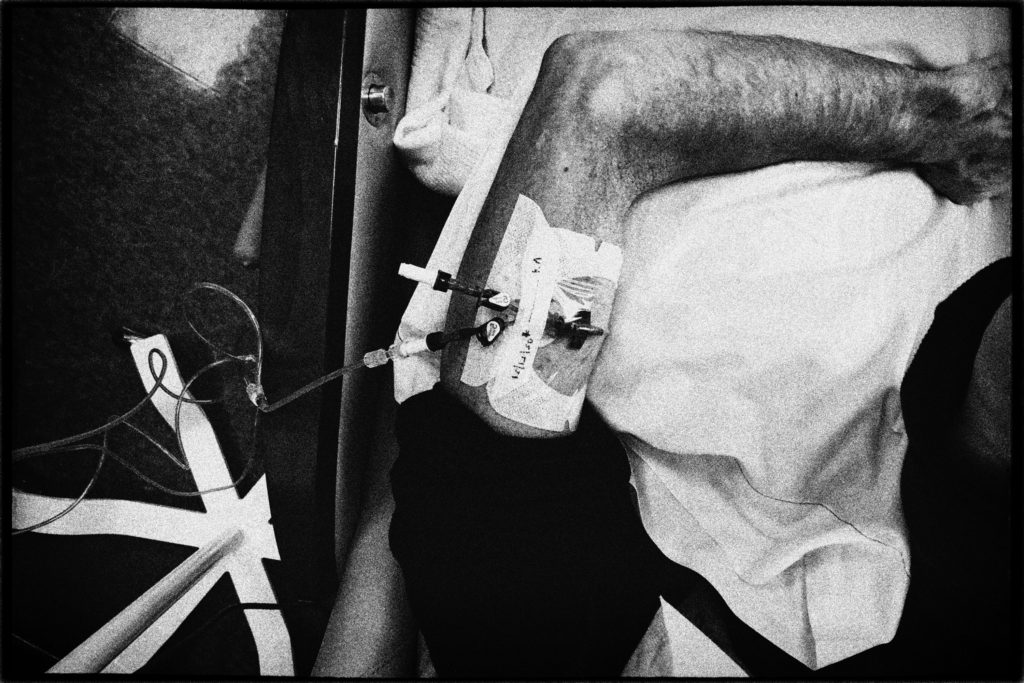

An Emergency In Slow Motion

Self Portrait with Feeding Tube, Raleigh, North Carolina, November 2020

I’ve been reading up on Diane Arbus recently. She’s someone I’ve always known about but never really taken to; there’s something off-putting about her work that makes me queasy when I look at it. It bothers me. I don’t think it’s because of the common criticism of her – she’s “exploiting” her subjects for her benefit; we, by definition, “exploit” the people we photograph – so much as what it says about her. Her daughter, Doon Arbus, in her postscript to the posthumous publication entitled Untitled, claimed her mom “wasn’t interested in self-expression,” which is a stunning misunderstanding coming from someone who should know better.

As William Todd Schultz argues in his fascinating ‘psychobiography’ of Arbus, An Emergency in Slow Motion: The Inner Life of Diane Arbus, Arbus’s work was all about herself, her externalization of an inner world produced by individual trauma. I recommend Schultz’s book to anyone interested in understanding the artistic process and what creates and nurtures it. From what I can see, Arbus had one fucked-up internal life. Maybe it explains why she took her own life at 47. Insofar as any work of art can be ‘explained,’ it explains it, or, at the least, puts it into a context that helps open up a dialogue with the artist and enhances the experience of the work itself. It’s made me rethink her work as something she wanted to tell me.

All of this is prelude to the fact that I’ve been contemplating documenting my recent medical experiences and putting them out there for you. You could read that as objective documentation or shameless self-absorption, depending on how you feel about what motivates these ‘documentary’ desires. What’s so special about me and my experience? Nothing. That doesn’t mean it isn’t my experience, and it doesn’t necessarily preclude me from sharing it with you in a way that might – just might – mirror to you your own experience in some way. It can easily lapse into vulgarity, become a cheap attempt for attention or sympathy, but I’ll assume the risk. Frankly, the attention doesn’t interest me at all. When I started Leicaphilia years ago I did so with the intention of remaining anonymous, and I kept it that way for a number of years. But as time passed, and readership sorted itself out, I gradually engaged the blog to discuss more personal things, which seems more in the spirit of what I do as a ‘documentarian.’ Isn’t that the function of ‘documentary’ photography? The alternative is pictures of cats and fence posts.

*************

Checking in for Chemo

So, as regular readers know, I’m currently in the process of beating cancer or having it beat me. Stage Three Stomach Cancer. Nothing more traumatic than what millions of people experience every day for any number of reasons. Actually, I’m tempted at times to see my current travails as a blessing, a pedagogy about life, its value, and maybe even its meaning [I’m still unsure about the latter]. But it’s occurred to me that it would make a potentially interesting photo essay, and Leicaphilia gives me a platform to present it. So, that’s what I’m going to do, among all the usual things, going forward. Or, at least it’s what I’ve chosen to do today.

All of the photos below were of my chemo visit yesterday. Today I’m home, hooked up to some Frankensteinian device pumping poison into my system for two more days, after which I get monitored to see if my white blood cells are falling dangerously low and potentially necessitating another hospital stay. Luckily, my oncology doc tells me I’ve apparently got a very strong immune system. My white blood cell counts remain normal after chemo. As such, I don’t require the $8000 shot usually given to people after each chemo round. $8000 each shot, money upfront. That’s $64000 out of pocket for 8 rounds, not covered by any insurance I possess. When they scheduled me for it and explained the cost, I laughed. Right, like that’s gonna happen. America health care – all I can do is shake my head.

What Exactly Does it Mean to Have “Good Taste”?

If You Don’t Like This Photo, You’re Not a Very Good Person.

As anyone who has perused a ‘photo critique’ website knows, there’s a fine line between respecting others’ right to their bad taste and opting to participate in it or encourage it. There’s a lot of truly awful photography peddled via the internet..or, at least, that’s my take on it. Most people would reject my judgment as snobbish. Taste is taste; who am I to pass judgment on the tastes of others, right?

The question is the degree to which peoples’ inability to agree about aesthetic matters is itself something we can agree on (i.e. it’s all simply a matter of ‘taste’), or is there something objective we can point to when arguing for an aesthetic standard? Is my claim to recognize ‘good’ versus ‘bad’ creative expression simply subjective or does it entail an objective standard that I’m in possession of?

The post-modernist belief is that the plurality of aesthetic points of view is the necessary result of the diversity between human beings. This is a good thing, and we should celebrate the fact that we are all free to judge for ourselves what appeals to us. We moderns think of aesthetic disputes as reflecting a person’s ‘taste’. There’s no arguing over taste, the assumption being that taste is subjective and therefore unimportant as a means to differentiate people. I don’t believe that, and one look at your average photo enthusiast website should be enough to convince you I’m right. I believe a proper understanding and recognition of superior aesthetics is something one develops. It’s a skill learned like any other. Some people possess a better understanding of it than do others who are too slow to understand what they don’t know – think of it as the Dunning-Kruger Effect applied to aesthetics.

*************

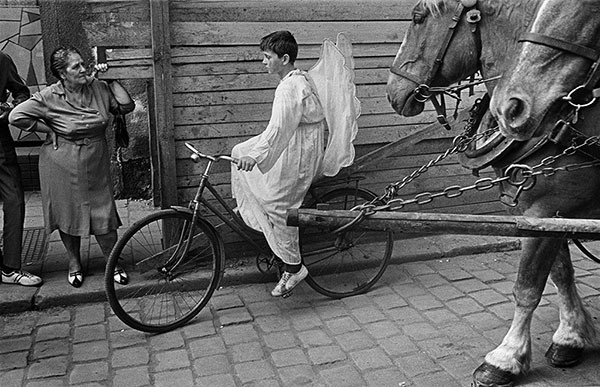

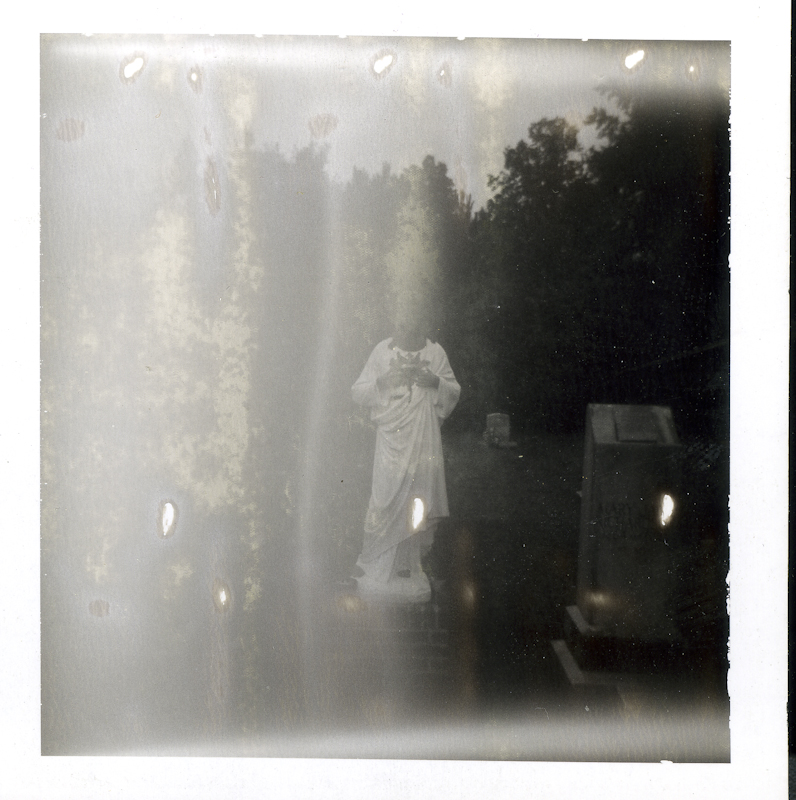

This is a Good Photo. Those 3 Birds Make It. Somehow I Forgot To Include it in Car Sick.

The Ancient Greeks agreed with me. They believed in an objective standard of the beautiful, a standard that was, in theory, available to any rational person. In the Euthyphro, Plato, via the voice of Socrates, claims that our disagreements always involve one of two subjects: ethics – how to act – and aesthetics – what is beautiful – in his words those that have as their subject matter “the just and the unjust, the beautiful and the ugly, the good and the bad.” In various Platonic dialogues, you’ll often read of some horny old philosopher praising some nubile young boy for his noble birth, his virtuous character, and his handsome body, all at the same time. That’s because in ancient Greek, the word “kalon” (‘noble’ ‘virtuous’, ‘handsome’) fused aesthetics and ethics into one thing. The beautiful was just, and the just was beautiful. Likewise, the trite or banal or vulgar was ugly and unjust, and those who mistook it as beautiful were compromised personally. They were, in a real sense, deformed.

For Plato, your ‘tastes’ irrevocably reflect your status of personhood. They indicate your progression in the state of being. They are a badge of your refinement, a refinement developed through your concerted effort. It takes a lot of intellectual and spiritual work to recognize the beautiful and embrace it when most others cannot or will not. It takes knowledge and courage to reject the facile sub-standard banalities that so often are publically celebrated as virtuous. Plato has no problem with you pointing and laughing at the guy sporting the Canonikon with 17-280 kit zoom who would look at Robert Frank’s The Americans and criticize it for not respecting the Rule of Thirds.

Your tastes in effect define you as an ethical person. In fact, your tastes constitute an ethics in themselves; if you have “bad” taste, you are, in some sense, a “bad” person i.e. deficient in some way. Likewise, having “good” taste makes you a “good” person, and this aesthetic divide between two human beings obstructs their ethical relations. I suppose it’s why I find the usual suspects – the guys flogging their association with Leica as a badge of their creativity, when in fact it’s just the opposite – so pathetic. Plato would find them pathetic too.

Analog Activity/Digital Passivity

“Certainly it would seem that TV could become a kind of unnatural surrogate for contemplation: a completely inert subjection to vulgar images, a descent to a sub-natural passivity rather than an ascent to a supremely active passivity in understanding and love.”- Thomas Merton, 1948.

At about the same time as the Trappist monk Thomas Merton (1915-1968) was complaining about the “inert subjection to vulgar images” produced by the then-new technology of television, German phenomenologist Martin Heidegger was making a similar point about the typewriter. Heidegger did so by harkening back to another philosopher, Plato, and his critique of technology and its effect on how humans create their worlds. Plato claimed that the ‘technology’ of writing degraded the primacy of the spoken to the detriment of our sense of reality; 2400 years later, Merton and Heidegger would be doing the same for the typewriter and television. Each in some sense represents a degradation of the human ability to experience the real by abstracting it a degree from reality. By removing the speaker from the spoken, Plato saw writing as a first step to the dehumanization of communication; by veiling the essence of writing and script, Heidegger claimed that the typewriter “withdraws from man the essential rank of the hand, without man experiencing the withdrawal appropriately and recognizing that it has transformed the relation of Being to his essence.” In other words, the typewriter, like writing for Plato and television for Merton, removes us a certain degree from experiencing the thing itself by doing it and in so doing makes us passive observers in what were heretofore active experiences.

I couldn’t help but think of Plato (and Heidegger and Merton) while bulk developing a ridiculous amount of film that I’ve accumulated over the last few years. The COVID quarantine has given me the perfect opportunity to finally do what I’ve been putting off for years. I’ve been shooting film and then throwing the canister into a bag full of other exposed films with the understanding that I’d get around to developing it all someday. That day has finally come. I’m bulk developing and fully scanning 8 rolls a day until the backlog is resolved…after which I intend to be a dedicated film photographer again, keeping to my promise to immediately develop and scan what I shoot. It’s a great plan that makes me happy, because I really do love the hands-on experience of shooting film, the deliberateness and intentionality of the practice and the end result of a physical thing that I can file away. Granted it’s a PITA, but the doing of it brings me back to a place where photography is both a creative pursuit and a craft, and it has the added benefit of connecting you back to your photographic tools in a way that’s missing with the quick and easy experience of digital.

*************

I Found This Among What I’ve just Developed – Lexi, Who We Just Put Down After 14 Years, As a Younger Pup, Ever Hopeful of Snagging a Bit of Pizza. An Unexpected Gift From a Roll Exposed Long Ago. Makes Me Smile Even Today.

Aristotle spoke of entelecheia, where the end and actuality of a thing are internal to its own activity. He thought the most rewarding experiences are those things we do solely for the pleasure the doing itself generates and not those things that are done as means to an end, and he thought that entelecheia was most often a result of solitary pursuits. This has always been my experience of photography: I do it for the pleasure of doing it, nothing more. And I do it to be in my own head and no one else’s. The end results – boxes of prints and innumerable binders of sleeved negatives and hard drives filled with DNGs – are secondary results of the process itself and the rewards those processes afford us. I think that’s why the transition from analog to digital has been unsatisfying for many of us. It lessens the creative involvement inherent in physically instantiating activity and replaces it with the passivity of pressing buttons and being given a result with little physical or psychical work involved.

Doing film photography is to reorient yourself to our own embodiment. You are creating something instead of entrusting the decision to a computer and an algorithm mindlessly running in the background. It is also to be disengaged from the virtual environment, which is always fundamentally social in nature. Our use of technology militates against solitude if we define such as the absence of input from other minds. Doing photography digitally is always, at base, a collective creative pursuit even when no others are physically present. Whether via the use of apps that presuppose other’s connection to our pursuits, or simply the use of necessary technologies that are the results of input from other minds and their implicit creative biases, your creative digital decisions will always be, to some extent, circumscribed by the decisions of the people who’ve programmed the digital tools you employ or are on the receiving end of your digital solicitations.

Ok, So…..

This Made it In, But Barely

…I’m currently holding two printed proofs of Car Sick, one printed in B&W, the other printed in CYMK. They both look really good, although the CYMK prints out much better than B&W; not even close. The blacks are much deeper, and there’s no obvious color cast. Lesson learned: when done professionally, and not knocked out quick by a POD or some similar vanity press, you can get nice B&W from four-color printing. I’m pleased. The final version is 100 images on 140 pages, 100# weight gloss fine art paper printed at 436 PPI, cloth hardcover with a printed jacket. All the upscaling – four- color printing, heaviest gloss paper stock, dust jacket etc, -bumped up the production costs significantly, although you (and I) are worth it. By time I ship them out I’ll be losing $10 a copy, so I’m pleased I didn’t quit my day job. Full run of books should be in my possession June 1st.

Actually, I’m really pleased with the quality of the entire project, content included. In addition to the photography, I did all the design myself. Before submitting a final I sent drafts to someone I respect for some feedback. This is what I got back: “I was somewhere between delighted and gobsmacked at how good this thing is. I was expecting something good, but not *this* good. You have many excellent spreads in here, and all the photos are strong both by themselves and in sequence.” Even factoring in some inevitable inflation in positive response baked into any unsolicited request for feedback among friends, I took this to mean I was on the right track. Of course, I proceeded to substantially revise it further, taking out a few photos that worked on their own but ‘didn’t quite fit’ into the larger sequence, adding a few which hadn’t previously made the cut, and re-sequencing in light of the changes. I like the final copy better than what I sent out for comment. Readers will have their say, of course, but I like it, and that’s what matters.

It’s interesting how much weight sequencing plays in a successful visual presentation. Properly done, effective sequencing – i.e. placing photos in positions where they relate to one another and create a larger narrative via the relationships created by recto/verso page layouts and beginning-to-end sequencing – makes the difference between a good, coherent work and a not so good collection of vaguely related photographs. The trick is to 1) present a body of photographs that relate to each other and in-so-doing create something bigger than a mere collection of ‘good’ photos; and 2) sequence the work so that it has some narrative structure without forcing a structure on the viewer. Editing for sequence requires a light hand; you want the viewer to retain some imaginative input – nothing worse than force-feeding a point-of-view – while offering something with some fundamental coherence. It’s a variation on the post-modernist question of who determines the meaning of a piece, the author or the reader? I come down on the side of both. That’s why it’s possible that I’ll love the book and you’ll hate it. Who knows? Who cares? You’ve already paid for it, so you’re stuck with what I give you. After coming up against the hard reality of all the work it was to involve, I – just fleetingly, mind you – thought of cranking out some easy POD and then ghosting you all. Couldn’t do it, given how generous all of you who contributed were and are.

*************

This Was Taken Out of a Car Window…But this Didn’t Make it In (Not Shot in USA, Doesn’t ‘Fit’ Any Conceivable Narrative Sequence), Plus, Most People I Show It To Hate It. I love it…But It Doesnt Fit.

On a related note: Within a few days I’ll be posting a bunch of photo equipment for sale, in what has become my usual annual disgorgement of stuff I’ve bought on a whim and now need to unload to scare up some cash. The reason I’ll be doing so is that, as mentioned, I’m over budget on the book, and I need to raise some cash so I can finance sending 90 copies to readers around the world without my wife leaving me.

In spite of my protestations to the contrary, half the fun of a photography obsession is fetishizing equipment, and, true to form, I’ve accumulated a bunch of really nice cameras I thoroughly enjoyed using for the minimal time I owned them but have tired of them and now, in the interests of financial solvency, need to move them along to the next gearhead. Who among us doesn’t secretly covet new-fangled stuff that promises to finally satisfy whatever the underlying causes of our perpetual discontent? Plus, it’s fun to get new stuff, real fun if it’s actually something of quality that works well and not some ridiculous limited edition Lenny Kravitz thing Leica conned you into buying so you’d vicariously feel like a mix of Don McCullin and Jimi Hendrix while stalking your subjects at the corner cafe. Suffice it to say that I wouldn’t sell anything to my readers I wasn’t prepared to buy myself.

Yes: Car Sick is a Thing

For all of you who so graciously purchased a copy of Car Sick on my word that you’d someday see something, I’ve not been intending to fleece you, although, in light of my disappearance from the site for the last few months, I understand if that’s what you were thinking. An explanation is probably in order.

Chalk it up to ‘artistic temperament.’ A few months ago I ‘hit a wall’. It happens. I find when it does I just need to wait it out and eventually some sense of inspiration will come back. My procrastination was compounded by a number of personal matters, details of which I won’t bore you, except to say that a switch from open-source Scribus design software to Adobe’s InDesign has been helpful and I’ve got a final PDF printable draft ready to go.

Final copy will be clothbound 7×10, 120 pages with 80 B&W CMYK printed photos. All design and editing done “in house” i.e. by me. I like it and trust you will too.

I’ll keep you updated as production proceeds. Thanks for your generosity and your patience.

Covid-19 Ennui

My Kid and My Cat in Lockdown

Like most of you, I’ve been home during the Covid-19 thing. In addition to attempting to single-handedly run a professional office from home, I’m in the middle of a Harvard graduate seminar that is requiring insane amounts of work, and on top of that I’ve been consistently sick with some sort of viral thing (don’t even suggest Covid-19; my wife won’t hear of it, even though I started feeling bad after meeting family members in Florida for a family get together beginning of March, my brother coming from Albany, GA (subsequently known as Georgia’s Covid-19 hotspot), my mom coming from NYC. Coincidence?). Plus I’ve got to get a Car Sick book to at least 80 of you who have already paid for it. Throw in the fact that I’ve been suffering from a complete lack of inspiration, and it’s been, to put it mildly, an interesting last month or so.

I’m feeling much better, except for the cabin fever. Car Sick is now back on my radar. I’ve got a final draft and now am debating whether the photos should be printed greyscale or CMYK. If CYMK, then I’m going to have to redo all the photos to make sure they have the same tonal values. The publisher tells me CMYK is preferable; why I’m not sure, given printing greyscale would obviate the need to standardize tone between individual photos. Plus, as I’ve tried to explain to them, 1) I’m not Ansel Adams; and, 2) most of the photos were taken out of car windows.

*************

As for photography-related activities, good documentarian I am, I’m taking pictures of the goings-on inside my house. Lot’s of cat pictures, as befits a Leicaphile. I’ve been periodically fighting the urge to buy a Monochrom just for the hell of it, but, of course, that’s not going to do anything but reinforce what I already know, which is that it isn’t about gear….except that it is. After having pondered the question for years now, I’ve concluded that my love of film photography is closely related to the specific ‘look’ of 35mm B&W and, to duplicate that look digitally, you need a decent APC-S sensor from the 6-8mp era. It’s going to give you the approximate resolution of 35mm film and the same approximate ISO sensitivity. And you need Silver Efex.I’m especially happy with the B&W output from the Fuji S5 Pro. Coupled with Sigma’s 30mm f1.4 ART lens its output gives really nice files you can turn ‘film-like’ with minimal effort. What would possibly be the purpose of a Monochrom then?

For Want of ‘Dietrologia’

Italians have a word dietrologia — literally translated as “behindology.” It’s the art of looking behind the surface of things to find their meanings, the hidden meanings of things. The Italian dictionary defines dietrologia as the “critical analysis of events in an effort to detect, behind the apparent causes, true and hidden designs.”

I’m pretty sure it’s a necessary trait for creativity, the ability to see more than the surface of the thing. Creativity is the ability to generate novel insights, to see behind the surface banality of a thing and suggest a glimpse of what it might mean if looked at from a novel perspective. To do that, it helps to have a head full of other things – things you’ve seen, and experienced and read about or heard or thought through. All of these things you weave together with what you’re observing and the end result is seeing something new.

The trick, of course, is to possess the ability to show others what you’ve seen. Successful creatives communicate their visions. Think of someone like Martin Scorcese in film, Trent Parke in photography, John Coltrane in music. They each have a unique vision that ties together their work and makes it theirs, and they possess the skill to tell that vision to others. There’s two parts to the creative equation – 1) seeing, and 2) telling. In order to be successful creatively, you need to be good at both. Unfortunately, recently I’m having trouble with both. I used to be a fairly proficient dietrologist. Lately, not so much. I’m, as they say, stuck, seeing nothing new or interesting. I’m hoping that eventually changes. Who knows. If past experience is any indication, one day I’ll wake up and see compelling pictures everywhere.

*************

According to 19th-century art critic John Ruskin, the “greatest thing a human soul ever does in this world is to see something, and tell what it saw in a plain way.” I’m not sure I’d go that far, but I do agree to the extent that seeing and telling seems a uniquely human thing to do, and it’s something really important to us, both as individuals and as a species. And specifically, image-making – a type of seeing and telling – is a necessary part of our emotional, psychological and intellectual make-up.

Literally, the earliest evidence we have for human culture are images, paintings of animals deep within caves that date to times before we’re sure humans even possessed language. The cave paintings of Pech Merle, Font-de-Gaume, Rouffignac, Chauvet and Lascaux are thought to be more than 30,000 years old. Bisons, lions and other extinct creatures cover the cave walls. What’s interesting about these pre-historic cave drawings is their undeniable aesthetic quality. Whatever their purpose, it was more than just transmission of knowledge, as some anthropologists claim (i.e. information about the location and movement of prey animals etc); there exists a vision behind these images, a felt need to communicate something aesthetically, the same thing that motivated Boticelli or Jasper Johns…or Walker Evans. Many animals are depicted in vivid color, with a sense of perspective and anatomical detail requiring significant artistic skill. Picasso was awed by their aesthetic power. “We have invented nothing,” he remarked after a visit to Lascaux in 1940.

*************

The question is why the ability or desire – or both – comes and goes as it does. Part of it, for me, has been the exponential inundation we’ve experienced via digital media. Technologically compelling images are everywhere, and, as such, they no longer have any value because they have nothing beyond their surface glossiness. They say nothing by representing everything superficially, everything glossed over with the hyperreality of marketing. They’re meaningless visual trinkets mindlessly created and consumed, all alike in their technologically mandated perfection. They represent the antithesis of a unique vision, all surface, saying nothing.

I started Leicaphilia years ago because I thought there needed to be someone advocating for film photography before it was totally swallowed up by digital. In the years writing it I’ve come to see the issue in more nuanced terms. What I’ve been really criticizing is the conflation of excellent images with images that rely on technology for their visual interest. Maybe shooting film is a self-imposed means to marginalize the ability of technology to hijack the creative process for its own ends. But, let’s face it – shooting film is a pain in the ass. Mind you, I ‘love’ the process, but I’ve come to realize that you don’t get points for difficulty. As to its success or lack thereof, a photograph stands on its own. It doesn’t matter how you produced it. Or does it?

Curbed Enthusiasms

Havana, 1998 – Recently I’ve Been Feeling A Lot Like This Guy

The source and nature of inspiration has always been an interest to me – where it comes from, how it manifests itself, where it goes and why. Photographic inspiration particularly. I’ve been fascinated by photography since I was a kid; it’s one of two long-standing interests in my life, the other being motorcycles. Yet even the strongest enthusiasms occasionally wane. Given some time, and a respite to clear my head, my interest returns, stronger than ever.

I’ve noticed that my photography and cycling interests are interrelated. When one waxes the other wanes. My photographic interests have been fairly constant – except for those times I’ve been accommodating my interest in motorcycles. I’m either obsessing about black and white film photography and photographers and photographic tech – or I’m dreaming about racing motorcycles – power to weight ratios, reciprocating mass, fuel injection mapping, favorite tracks etc. I’m rarely dong both at the same time. Apparently, both speak to the same need, a need that manifests itself in me in differing ways – aesthetics vs. speed. When the need is fulfilled in one manner the other becomes dormant.

Havana, 1998

I am currently experiencing a complete lack of interest in things photographic. Complete. I’ve not written for some time because I am totally devoid of things to say. This is highly unusual. I’m typically in a frame of mind where I can effortlessly crank out semi-intelligible thoughts marginally relevant to the subjects we discuss here. Often, when I’m a bit more inspired (my wife would say ‘manic’) I can write 3 or 4 posts in a day. Likewise with ‘seeing’ photographs. When it’s there it’s there; it’s a gift that comes unbidden on its own terms. I see what look like compelling photographs everywhere, seemingly the most mundane things transformed aesthetically via grey tone, film grain and 2×3 format. It’s an incredible blessing, making even the most banal aspects of daily existence pregnant with possibility.

The converse of this is that inspiration can leave as quickly as it comes. It’s why the Greeks talked of a ‘muse’, a spirit we all had access to that inspired us in a time and manner of the muse’s choosing. Apparently, my muse has decided I need a break from ‘thinking photographically.’ One thing I have learned – it’s best to respect the coming and going of one’s muse, and certainly not try to force her hand.

*************

My latest interest – a KTM RC390 (highly modified, more to follow)

Sometime around the new year I started getting an acquisitive itch. Had to buy something. I’m not too proud to admit that I often suffer from the vulgar desire to buy things, things that I know, deep down inside, will not make me happy. I had some money in my pocket, I’d been a good boy for some time, and now I wanted to indulge myself, damn it. My first inclination was to buy a camera ( as if I needed another camera). I thought of a Monochrom. Why not? I could write about it on Leicaphilia. When I tired of it, as invariably I would, I’d sell it to a reader. And then I fixated on an M262, the digital M without the screen. Very cool, very old-school but without the hassle of scanning film etc. I’m certain I could find some high-handed way of justifying the purchase in spite of my claimed aversion to digital capture – I’d think of something.

And then I ran across a local craigslist ad for a KTM RC390.

I’ve ridden motorcycles for as long as I’ve photographed. I bought my first bike, a 900cc Kawasaki Z1, in 1976 when I was 18, but my older brother had numerous motorcycles – a Benelli 50, Honda 160, Honda 450 – that I’d sneak out of the garage when he wasn’t looking, so I basically grew up riding bikes. Marriage and the inevitable compromises of life temporarily halted my riding, but after a divorce I rediscovered my love of bikes in the form of a fascination with Ducati racing motorcycles. The mid to late 90’s found me with 6 Ducati’s in the garage, a few I raced, others I brought to track-days and ran on the backroads, usually illegally. Like all my enthusiasms I went in all the way, starting a company that made titanium parts for Ducati’s, the profits of which funded my racing. I also ran with a bunch of hooligans half my age who lived for doing crazy shit. Running from hapless police was an especially fun affair. Wonderful times, lot’s of testosterone fueled foolishness, a bunch of broken bones and one airlift to a trauma unit. It was all incredibly crazy fun and daring…life lived at the limits.

Falling off a bike going 140 mph and getting up and walking away can make you think you’re immortal. Of course, eventually the bill comes due. In 2011, my riding buddy killed himself on a group ride, losing the front end on a sweeping backroads curve at about 120 mph – nothing that hadn’t happened before and that he had walked away from, except this time he didn’t. Totally his fault, a result of his own recklessness, but that didn’t make it any easier. Pulling off a man’s helmet to find him dead is a sobering experience, certainly when it’s a 34 year old ‘kid’ – a genuinely good guy with a full life ahead of him. Shortly thereafter, after coming within an inch or two of killing myself and someone else on another group ride, I sold all my bikes and promised the people who love me I wouldn’t ride again. Looking back on it now, I’m amazed I’m alive.

And then, a month ago I bought another bike, the one you see above. I’ve compromised – it’s 373cc, and won’t go faster than 110 mph. But damn, you can have a lot of fun getting it there. I’ve ordered a set of BST Carbon Fiber wheels – reducing reciprocating mass is critical for the performance of smaller bikes – and have signed up for some track time. Hopefully the wife has forgotten my last track day – a nasty ‘lowside’ and a broken wrist. Of course, I’ve also been shaking it down on North Carolina backroads, fake plate, riding like a maniac. What can possibly go wrong, right?

As for photography – I’ll keep you informed. I intend to start posting again on a regular basis, and the work proceeds with getting a final copy of Car Sick out to the printer and into your hands. In the meantime, you can find me running the backroads on a seriously tricked out RC390.

Happy New Year

Here’s hoping you got that Lenny Kravitz Drifter Leica for Xmas. I’m taking a short sabbatical, will probably be back in a week or so. Unfortunately, I’ve been busy with other commitments and, coupled with ongoing computer issues, I’ve not given Leicaphilia much thought. I can assure you that will change, although I’m not exactly sure when.

Thank you to everyone who advanced purchased a copy of Car Sick. If you’re on my gofundme page as a donor, no worries, you’re gonna get a book…or two. I’m thinking March or thereabouts. Frankly, I’m stunned at how many of you chipped in. I’m grateful to each and every one of you.

Robert Frank and I Agree: Photography Should Be Fun

I’ve not been posting much lately. I’ve been busy, the website crashed for a while, I’ve just finished writing a 25-page proposal for a photography exhibit entitled The One and Only New Truth, and I’m trying to finalize a maquette of Car Sick. Photography hasn’t been ‘fun.’ It feels more like an obligation.

I’ve just finished reading RJ Smith’s biography of Robert Frank, American Witness: The Art and Life of Robert Frank. After publishing The Americans, Frank stopped photographing. He was sick of it. It wasn’t fun; it was now an obligation. At its best, it had functioned as a pre-verbal means of showing a truth, something he couldn’t articulate with words or logic. Frank was remarkably obtuse in explaining his photography. He hated it when people asked him about it. That wasn’t the point, his explanation. A flowery explanation might be facile and clever…but wrong. Just look at the pictures; you didn’t need his help.

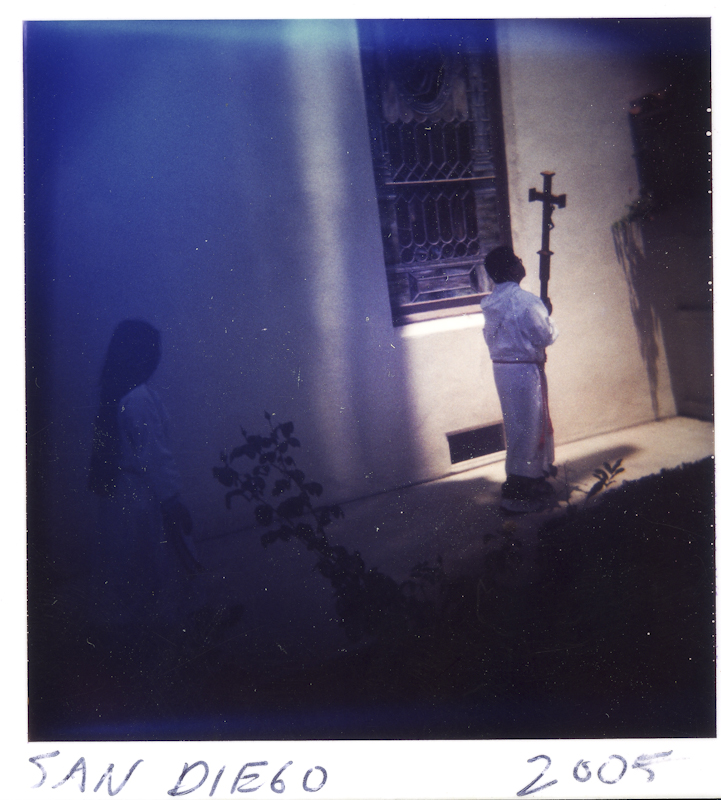

He never really went back to still photography, having transitioned to film. Only in his later years, living in the Nova Scotia wilds, did he dabble again in photography. His choice of camera was a Polaroid, something quick and easy, without artifice, that gave him lucky accidents. Frank always claimed that his best photography was accidental, nothing much really, just random snaps that produced serendipitous results. Of course, it was more than that; it was an eye that had been rigorously trained to understand the exceptional in the serendipitous when it occasionally occurred.

*************

By chance, having finished Frank’s book, finished my proposal, put aside Car Sick for a few days, I opened a box and found a series of polaroids I’d taken on a trip to the west coast in 2005. I had just come back from Paris, where I had been involved in all sorts of photography related stuff. I was sick of it, much like Frank was sick of his photography, apparently sick enough of it that I decided to leave my cameras at home and take an old Polaroid and some outdated film. I’ve posted some of the photos. Nothing special, but fun. I’m sure more than a few of you will think they’re shit. Be that as it may, I like them. I was clearly having fun again.

What I Don’t Want for Christmas

I don’t want a Leica watch. For that matter, I don’t want a Leica camera. I don’t need another Leica. For that matter, I don’t want or need any other camera, whether it’s a Leica, a Fuji, a Nikon, a Sigma or any other shiny new thing that promises to ‘complete my photographic journey.’ I’m not on a ‘photographic journey’, which is stupid adspeak designed by some clever guy in a hi-rise on Madison Avenue to bypass my critical faculties in the interest of selling me his widget. Even if I was, a new camera wouldn’t get me anyplace my current crop of cameras – all bought back then with the understanding that they were going to somehow make my photography better, my journey complete – can’t get me.

I’m sick of technical squabbles and little minds arguing irrelevant issues as if they were a matter of great import. News flash: the camera you use doesn’t matter. Not one fucking bit. The sooner you realize this, the sooner you stop obsessing over whatever new technological gimmick Leica or Nikon or Fuji is selling you, the sooner you’ll open yourself up to what really matters, the things that will make ‘your journey’ better. One thing I have learned is this: equipment is irrelevant. Nobody’s photographs got any better, or any worse, because of the equipment used. It’s like thinking the brand of instruments played on Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited is the reason it’s a 20th-century American music masterpiece ( it is, BTW, and I will fight anyone who is ignorant enough to claim otherwise (although you can make an argument that Bringing It All Back Home, released just 5 months prior to Highway 61, is even better)).

I’ve been looking at a lot of superb photography recently, enrolled as I currently am in a graduate seminar that requires me to look at photography. I’ve learned an incredible amount about photography in general while studying the specific genre of photography called photojournalism, which is surprising since I thought I basically knew everything there is to know about photography, its history, its theory, its practice. In fact, while I know a lot, in the larger scheme of things I know very little. Sometimes it’s good to be reminded of one’s ignorance; it can motivate you to put aside a lifetime of unconsidered opinion – the common sense ignorance one reflexively absorbs via one’s culture – and actually think about things minus the preconceived notions that inhibit what we think…and what we see.

************

Jean Gaumy, La Dune de Pyla, France 1984

Above is a photo by Jean Gaumey. I’d never seen this photo until a few days ago, when I stumbled across it while on a non-photography related website. Gaumy, while a Magnum member, seemingly isn’t that well known here in the States (or at least, I’d never heard of him, which may be a different matter entirely). It’s just a picture of a guy and a woman and a dog. In this sense, it reminds me a lot of Gianni Gardin’s 1959 photo below:

Both are simple subjects, simply visualized, but both remarkably evocative and powerful. Their power isn’t derived from any technical sophistication – both are shot with film, Gaumy’s looking like he used a 28mm optic, Gardin maybe that or a 35mm – but from an eye sensitive to subtleties of spatial relations, body expression, light, and mood, Both suggest something more than the sum of what’s pictured, the photographer skilled enough to offer an image for the viewer’s imagination. None of this has anything to do with the camera used. All of it has to do with the unique idiosyncrasies of the photographer’s understanding of the world.++

++ And, IMHO, the incredibly evocative power of the traditional B&W film look.

Up and Running

Sorry about the blackout. It couldn’t have come at a more inopportune time, having just asked everyone to fund my book…and then disappeared after taking in a quick two grand. Fortunately, it was just a ‘scheduled update’ that went wrong, and I’m lucky to have a friend with the knowledge to fix things.

I’ll be back to posting in a few days at most. For those who’ve contributed to my gofundme page, Thank you. I owe you a book. It’s coming, I promise. I’ll keep you updated as it progresses. I’m still taking donations. I’ll leave it up for another week or two, and how much I take in will determine the print run. I assume it’ll be +/- 80. I’m excited about it. Thanks for your support.

In the meantime, I’m reading RJ Smith’s bio of Robert Frank, American Witness, and following it up with Flash: The Making of Weegee the Famous by Christopher Bonanos.

Help a Brother Out, Part Deux

A few days ago I asked whether anyone would be interested in buying a book of pictures taken out of my car window. I figured I could guilt-trip a few of you into buying one. Surprisingly, between reader’s comments and private emails I’ve had over 70 readers request a copy and numerous folks asking for more than one. That’s really nice of you, and I truly appreciate it.

I’m not in this to make money. I’m good, thank you. What I am interested in is getting my work out there to people who might enjoy it, or learn something from it, or teach me something about it. My sole criterion in putting together the book is quality; quality of the photography and quality of the physical book itself – not some shitty POD book but a professionally done work that highlights the best of almost 50 years of snapping photos from the car. No throw-away images to pad out the work – I started with over 200 photos and edited down to +/- 80 final images. The criteria for inclusion of a given photo were three-fold: 1) does it work standing on its own; and, if so, 2) does it work as part of a larger narrative; and, if so, 3) is there a logical place within the sequencing where it maintains these two strengths? If I could answer Yes to all three questions, it’s in the book; if not, even if it’s a great single image, I tossed it. I tossed a lot, under the theory that usually less is more.

Much of it is film photography, much of it taken with a Leica of some sort, but that’s not the point. The point is to present traditional B&W photography that depends not on technical gimmickry but rather on the strength of the images themselves and what they both denote and connote, both as stand-alone works and as they’re sequenced into a loose narrative. I say ‘loose’ because photo books that focus too tightly tend not to interest me past a cursory viewing. The photobooks I keep coming back to – masterpieces like Mike Brodie’s A Period of Juvenile Prosperity – respect the viewer enough to allow him/her to create the narrative. For the same reason, there won’t be much text. You get enough of that here. In this sense, it aspires to be “Leica photography” in the best sense – quick shots caught on the run that say something, less dependent on technique than the photographer’s vision. If you’re looking for a photobook pimping for Leica or purporting to highlight the strengths of the Leica camera or optics, go elsewhere; this ain’t it. It’s not about the camera; it’s about the images.

Trim size will be 10×8 inches (width 10 inches, height 8 inches), paper heavyweight photo stock quality, sewn bindings, linen hardcover, +/- 120 pages with +/- 80 Black and White photos reproduced via CMYK printing. I’m making a limited edition run of 80 copies.

Price of the book will be $35/shipped within the US, $45/shipped worldwide.

I’ve started a “GoFundMe” site here, where you can contribute. Your contribution there will serve as your payment for the book itself. Of course, if you want to contribute less than $35, you’re welcome as well, but that would be sort of stupid because you wouldn’t be getting the book. Of course, you’re welcome to contribute as much as you want, but I don’t expect it and, if you’re feeling remarkably generous and contribute, say, $350, I’m sending you ten books.

I’ve seen proofs of a mock-up, and, it’s pretty good, not to blow my own horn or anything. It works. The last thing I’m going to do is send out bad work. Who knew photos out car windows could be so cool?