Thanks to theonlinedarkroom.com for the graphic ( A great website for the film photographer BTW).

Category Archives: Uncategorized

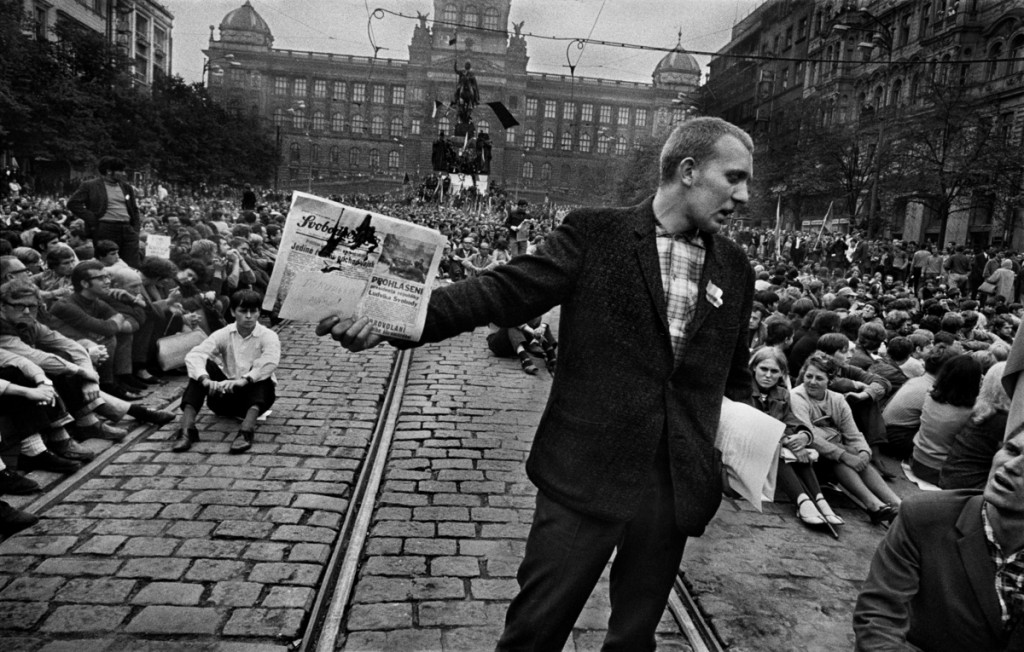

Magnum Photographer Rene Burri Dead at 81

In an email sent to members of the press Magnum Photo noted today’s death of René Berri: “It is with great sadness that we announce the death of Magnum photographer René Burri who passed away today”.

The Swiss photographer, who began working with Magnum as an associate in 1955 and became a full member in 1959, was well known for his work in Cuba, including his iconic portraits of Che Guevara.

In addition to his work in Latin America, Burri, who lived and worked between Zurich and Paris, travelled throughout Europe and the Middle East during his lengthy career, and contributed to publications including Life, Stern, Paris-Match, and The New York Times, among others. He also worked as a documentary filmmaker, participating in the creation of Magnum Films in 1965.

A retrospective of Burri’s lesser known color work, Impossible Reminiscences, was published by Phaidon in 2013.

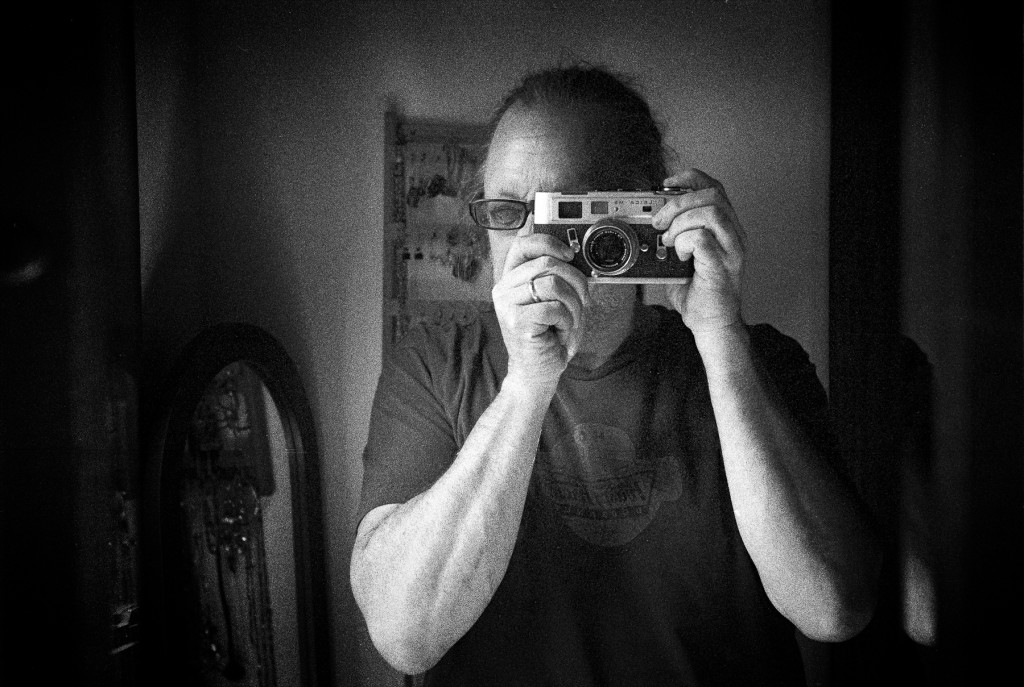

René Burri’s M3s

Millennial Nikkor-S 50mm 1.4 FOR SALE

FOR SALE: New, Unused Millennial Nikkor-S 50mm 1.4. $995/$20 insured shipping.

This Nikon NIKKOR-S 50mm f/1.4 is a limited-edition commemorative item built by Nikon in 2000 to sell along with the year 2000 Nikon S3. Nikon built about 10,000 of these in 2000 and 2002, sold only as a set with the Nikon S3 2000. It is a cosmetic match of Nikon’s 1964 version of the original 5cm 1.4 lens. Collectors dubbed the 1964 version the Olympic.

The Millennial’s optics are modern, and probably the best 50mm f/1.4 ever made by Nikon. It has a 9-bladed diaphragm and is multi-coated. It is super-sharp even at f/1.4, has less distortion than any other Nikon 50mm f/1.4 lens ever made by Nikon. In terms of micro-contrast and edge to edge sharpness it is a match for Leica’s $5000 Summilux ASPH.

The Millennial Nikkor can easily be adapted for use with Leica Ms via an Amedeo Adaptor.

Contact at leicaphilia@gmail.com

Jorge Fidel Alvarez: Street Photography With a Leica M Film Camera

Jorge Fidel Alvarez, Wuhan, China, 2014. Leica M6 and Tri-X.

Jorge Fidel Alvarez, Wuhan, China, 2014. Leica M6 and Tri-X.

Everybody does “street photography” these days. Go to Tumblr or Flicker and you’ll find reams of it posted day after day. Most of it is not very good, nothing but throwaway looks with no internal dynamic to make you look again. Just.people.on.the.street. Really good street photography somehow rises above the pedestrian view, revealing a greater narrative within a sliver of everyday life. There is always something surprising about it, something unexpected that draws your eye and makes you want to look again. It poses a question, draws you in for a second look, gives you a glimpse of something incongruous, something you don’t expect to see in the way you’re seeing it, inviting a unique interpretation for each idiosyncratic viewer.

Take the above photograph by Jorge Fidel Alvarez: A man, presumably, with a bizarre mask stands facing the camera, something decorative hanging over where he stands; his demeanor unreadable, maybe slightly menacing. The scene radiates something indefinably sinister. An elderly Chinese woman stands in the background, smoking, staring at either the masked man or the western photographer. I wonder: who in her mind is normal, and who is exotic? The photo fascinates me, but I’m not quite sure what I’m looking at, so I look at it again and fashion a narrative to fit what I think I see. The photo suggests various interpretations; its up to me, the viewer, to work it out for myself. (The masked man is actually a welder using a homemade steel mask, which, after the stories we’ve told ourselves, almost seems irrelevant).

*****

Good street photographers shoot a lot. The father of modern street photography, Garry Winogrand, using a Leica M4 film camera, shot over 12,000 rolls of film between 1971 and his death in 1984. When he died at the age of 56 he left over 6500 undeveloped rolls of film. Winogrand’s heirs, today’s street photographers, work in a digital age where photographs are cheap and ubiquitous, easier than ever to take, store and share. With the advent of camera phones, public resistance to strangers with cameras in public places has lessened. Yet exceptional street photographs remain as rare in the digital age as in Winogrand’s day. And almost no one shoots the street with film anymore. The ease of digital capture makes street shooting with film a proposition for only the most dedicated and hardcore film fanatics. So I’m fascinated when I see great street work done on film. Jorge Fidel Alvarez is a great street photographer, and he works with film.

Alvarez is a French photographer living in Paris. He is a 2004 graduate of SPEOS, Paris, where he studied under Georges Fèvre (master printer for Robert Doisneau, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and Josef Koudelka, among others). The Institut Culturel Français en Chine (The French Cultural Institute in China) recently invited Alvarez to Wuhan, China to shoot that city’s streets and exhibit the resulting work at the New World International Trade Center in Wuhan. The plan was simple: fly Alvarez to Wuhan for nine days of shooting whatever caught his eye, back to Paris for two weeks to process, select and print his work, and then back to Wuhan to exhibit 20 prints,, opening reception May 29, show to run through June 12. (details)

Jorge Fidel Alvarez, May 29, 2014, New World International Trade Center, Wuhan, China

Alvarez, who uses digital for his paying work as an architectural photographer, chose to use a Leica M4 and M6, with 25mm and 35mm lenses, while in Wuhan. (At least one Chinese reviewer found his choice of “antique cameras” memorable.) He shot 70 rolls of 36 exposure Tri-X over the course of 9 days.

Alvarez, who has been shooting the street since the 80’s when he bought his first Leica, took up professional photography comparatively late, after a first career in IT. He has carefully studied the work of other photographers – his Paris flat’s bookshelves are lined with the work of European masters Cartier-Bresson, Boubat, Koudelka, Lartigue, Doisneau, Frank. In 2003, enrolled in the photography curriculum at SPEOS Paris, he discovered the American Garry Winogrand. Alvarez’s mature work can hint at the European formalism of Cartier-Bresson and Boubat, and one see’s as well the more spontaneous elements of Frank, Daido Moriyama and Winogrand- but his vision is unmistakably his own, a fascinating amalgamation fusing the poise and balance of a studied, mannered aesthetic with the arbitrary and instantaneous.

Why I’ve Gone Back To Shooting Film…And Why You Should Too

Written by David Geffin, Reprinted from F-Stoppers, August 13,2014

Our DSLRs have confused us. We obsess over the wrong things. Sharpness at 400%; bokeh characteristics of lenses produced from what-must-surely-be prancing magical unicorns; high speed burst frame rates that make cameras sound like Gatling guns; 4k resolution to shoot better cat videos; 100 auto focus points that still won’t focus on what we need them to; and noise performance at 400,000 ISO. Absolutely none of these will make your photographs better. Shooting film will though, here’s why.

Last month, I bought my first film camera in a decade. A Leica M6. Yep say all you want to say about Leica users (it’s probably all true), this camera has changed the way I shoot, and been the single best investment in any piece of gear in years.

I grew up shooting film as a kid and we actually had an attic darkroom, thanks to my dad’s hobbyist photographer leanings. Shooting on film again isn’t some indulgent trip down a nostalgic lane though. It has snapped me out of the digital malaise and reminded me what it means to actually make a photograph.

What on earth am I actually talking about here? Well, our DSLRs turned us into the equivalent of photographic sloths. We wander about with too much gear, sluggish pulling the camera up, staring at our LCDs and wondering where all the love and emotion went.

Ok I’m being somewhat ridiculous, but I’m sure some of you out there in the back row are nodding in solidarity and agreement.

It’s not just me that feels this way. Last month I shot some video for Emily Soto for her NYC fashion photography workshop. As you can see from the video I shot, what is amazing to see is how much film features throughout the learning experience. The Polaroids, the Impossible Project film, and even the medium format and large format systems the attendees had brought along themselves – it all added to the overall aesthetic of the style of fashion photography that was being taught. Sure digital was being shot too – everyone had their DSLR, even a digital medium format camera was in attendance – but there was a definite sense of excitement when people shot Polaroid and revealed what had been captured.

The ability to shoot thousands of RAW images to a single card, to take a dozen images in a single second and to basically shoot as much as we want with almost no direct costs involved is turning us into brain dead zombies. So what can we do about it?

Is Film The Answer?

Film is just the medium. I don’t care so much about the medium (although I do love the look of film) – it’s the process that interests me.

Film forces you to work different “photographic muscles” much harder than when shooting digital. Here’s the ten things I’m now doing differently through the process of shooting film:

1.) I’m making selects in-camera, not in Lightroom

Film forces you to think about each shot, because each shot costs money. Film and developer costs are about 30 cents each time I click the shutter. That finite value of a limited number of shots on a roll, and developer expense makes me assess if it’s worth it before the shot, not try to weight it up after the fact in Lightroom. Less time in front of the computer, more time shooting makes me happy.

2.) I feel “the moment” more, and get a true sense of achievement

“What on earth is he smoking?”, you’re probably wondering? Well hippy’isms aside, you have no idea what you’ve got. No way to check an LCD. Each shot must be made to count (even if it doesn’t, there is a sense it should). Your confidence about “the shot” increases as you get more shots that work. When you get the developed film back and see you nailed it, there is no better feeling. Digital doesn’t come close to this sense of achievement. This isn’t about being elitist and shouting from your mountains “Look at me, I am the greatest photographer in the city because I understand how to shoot film!”. It’s about better understanding exposure, motion and light – and how that can help you in the digital world.

3.) You become more aware (particularly of backgrounds, light and composition)

This is easily one of the best skills I’ve become attuned to, and it’s translating into my digital stills and video work. Shooting black and white only has got me thinking much more about background and composition, and how light is falling on my subject. It’s adding greater depth to the images I take.

4.) I am being forced to better understand light

Although my camera has a built in light meter, I’ve become accustomed to different shutter and aperture settings in different lighting conditions. At first it’s a little tricky, even if you shoot manual in your DSLR. I also have a greater understanding of my reciprocals and have become much more adept at quickly adjusting shutter and aperture simultaneously, all of which translates into the digital world very readily. This is about being ready to capture moments while others are still fumbling with dials and settings.

5.) I can anticipate the moment better

My lens is manual focus, the camera is a rangefinder. I shoot at a snails pace now. This is a good thing. This is a great benefit of shooting with film, because it forces you to try and pre-visualize what you want to happen. If you are shooting sports, weddings, people or anything that is not still life, this is an essential skill to hone. The best photographs tend to be the in-between moments, those unexpected instances. Being quicker to anticipate these is a great skill

6.) I’m much more patient

I live in New York – any time I get a chance to practice patience, I take it. The more time I spend doing any type of photography, the more I realize it’s about shooting less, slowing down and observing more. Sure, there might be times you want to shoot off a huge number of frames each second, but if you’re trying to convey an emotion or evoke a mood, I think it’s far more worthwhile to wait, watch, direct a little and have a clear vision in your head AHEAD of what you shoot, rather than shooting and looking at images, trying to work out what you were trying to say. Shooting film is a cure for the over-shoot-because-we-can digital sickness I often find infected with.

7.) I’m no longer weighed down with gear

I cannot tell you how transcendentally magical it is to carry one lightweight film camera and one lens, a 35mm. I’m not only lighter, but I can see and frame an image with my eyes before I even pull the camera up. Shooting one camera and one lens allows you to pre-compose with practice, and is a great way to practice photography without shooting a single photograph. “Know thy tools so they get out of thy way” was some famous saying someone once probably said, and it’s definitely true.

8.) Between sharpness and a better photograph, sharpness loses everytime.

I love sharp digital images, don’t get me wrong, but I firmly believe our ongoing obsession with it is causing us to overlook our connection to the image. I mean, who doesn’t love poring over lens charts? Over sharpened, perfect images are like digital razors to my eyeballs. Imperfection is beautiful. Sharpness doesn’t make a good image, it can make a good image better (if used tactfully) but focusing on just getting something sharp can make an image lifeless and boring. I love the emotion of motion blur, and grain in film, it gives us something organic that connects us to the images we see. We’re humans, not robots, and some of the images I see could easily have come from the brain of an awesomely-cool-looking-yet-emotionally-barren android photographer.

9.) Post processing an image takes 30 seconds, not 30 minutes

Because I love the natural look of film, I’m rarely spending more than 30 seconds on each image when I am messing with them in Lightroom. I’m not spending as much time in front of a computer, I’m just shooting more and that’s what makes me happiest.

10.) Film is timeless

Whichever way you cut it, you cannot beat the look of film or it’s archival properties. It’s why Scorsese, Abrams, Tarantino, Nolan and other Hollywood directors pulled together last month, to try to save Kodak stock. Sure, it’s dying – Kodak film stock sales have fallen 96% over the last ten years, but the fact it’s still around, and still in demand by many top directors says a lot about the special place film has in many of our hearts

Final Thoughts

So am I done with digital? Of course not. In the space of a few days last week, I shot a Polaroid land camera and a Phase medium format camera. Different tools, different jobs.

Will my film camera replace my digital camera? Not on your nelly. That’s not the point of the article. Digital is great, but with all the cheap advancement in technology and limitless opportunity it brings, it can turn us into stumbling, photographic zombies if we’re not careful.

I am thoroughly enjoying the process of film again because I feel like I’ve been snapped out of the digital daze. It’s not so much a trip down memory lane but rather, a useful sharpener for my photographic skillset. You don’t need a Leica. A few hundred dollars gets you a cheap 35mm film camera, a lens, a basic-but-effective film scanner and some rolls of Tri-X to get you started. It’s hardly a serious financial risk and I’m wholly confident you’ll get a sense of at least some of my experiences. At the price of a cheap second hand piece of glass, what have you got to lose?

Using a Leica MR4 meter

An excellent tutorial on the use of the attachable Leica MR4 meter by Michael Geschlecht, from L Camera Forum:

The MR4 meter is a reflected light meter that couples to the shutter speeed dial of many M cameras. It has a sensitivity range of EV +2 to +18. That means with a film of ISO 100 It will give you readings from F1.4 @ 2 seconds to F16 @ 1/1,000th of a second. That covers pretty much of what most people need in many circumstances.

Once you attach it to the M3 it will read an angle of view more or less equal to the angle of view of a 90mm lens. This is the angle of view shown by the frame lines either when you insert a 90mm lens into the camera & attach it or when you push the lever under the large, clear viewfinder window in the front of the camera inward in the direction of the center of the camera. Until that lever stops moving. Regardless of the lens mounted. Unless the lens has permanently attached “goggles”.

If the lens on the camera has permanently attached “goggles”: Push that same lever outwards until it stops & use the 135mm frame. Sounds silly but it works correctly.

Replacement Wein 1.35 volt zinc-air “button” batteries are available. Just check in any camera store or find them on the net.

To mount the meter on the camera & properly couple it to the shutter speed dial:

First set the shutter speed on the camera to “B”.

Then pull out the film advance lever to the “stand off” position.

Then rotate the dial of the MR4 meter to “B”.

Then slightly lift up the shutter speed dial on the meter until it stops.

Then rotate that dial in the direction of longer exposures,ie: 120 seconds..

Then slide the meter into the accessory shoe.

Then rotate the shutter speed wheel on the meter back to “B”.

The wheel should now click down & the pin on the underside of the meter’s shutter speed wheel should drop into the little cutout between the “2” for 1/2 second & the either “4” for 1/4 second or “5” for 1/5 second. Depending on which model of M3 you have.

Look to see if everything engaged properly. If all is right you are ready to go.

A meter coupled to the shutter speed dial means: You only have to set the aperture after you make a reading. Unless the shutter speed set before you took the reading is not appropriate. Very fast & handy.

Alternatively, you can take a meter reading, then rotate the shutter speed dial until the aperture you want to use is aligned with the indicator arm. The shutter speed has also been correctly set for the proper exposure.

Whichever works in whatever direction is equally fine.

There is also a “battery check” slide on the front of the meter. If the meter arm goes up to or slightly passes the white dot: The battery is OK. The battery currently in the meter may still be OK even if it is years old. If these types of batteries are not used frequently they usually still last for many years.

USING THE MR4 WITHOUT SCRATCHING THE LEICA TOP PLATE

Often the meter will rub against the top of the camera and leave permanent scratches. This can be avoided by turning the appropriate leveling adjustment screws on the bottom of the meter’s mounting shoe. There are 5 screws holding the foot to the meter, 2 small ones & 3 larger ones.

If you look from the back of the camera, as you try to slide the meter into the accessory shoe, you can see if the screws need adjusting. There should be a clearance of about 1&1/2 mm.

The 2 tiny screws lift & balance the meter above the accessory shoe & the 3 larger screws lock the shoe & hold it in place. Like a tripod.

A little fiddling with the 5 screws as per above, if necessary, should set the clearance so the meter clears the top plate by about 1&1/2 mm while still allowing the pin to drop into the slot in the shutter speed dial on the camera when the shutter speed wheel is returned from somewhere in the 4 seconds thru 120 seconds range to the “B” position.

Once the pin drops down at the “B” position the shutter speed dial should be rotated to all positions to make sure that the pin continues to engage the slot & does not slip out between any of the the settings “B” thru “1000”.

Tri-X versus Silver Efex: Which is Which?

Above are two photos, both taken with available light in the same location at approximately the same time of day. One was taken with a Leica M4 and 35mm 2.5 VC pancake lens (a jewel of a lens, btw, and without doubt the best price to performance M mount lens in existence); the other taken with a Leica X1 and its 24mm 2.8 Elmarit, a rough 35mm field of view on the X1’s cropped sensor.

The M4 was loaded with Tri-X, rated at box speed of 400 ISO and developed in HC110 solution B. The X1 was shot in RAW and processed in Silver Efex Pro using the Tri-X emulation. Both were sharpened at output. (You can click on either photo to see a larger version).

Obviously, a comparison between two 72 dpi jpegs can only tell you so much, essentially how scanned film compares to digital files on a monitor. Scanning film brings an entire new technology into the mix, but then again so does the use of Silver Efex for digital files.

I’m a dedicated B&W film shooter. I love the look of film, its smooth tonality and its depth. In my eyes, its obvious when you look at a silver halide print versus a a digitally captured inkjet print. But I also see subtle differences in the examples above. The difference is still there when both are digitized and displayed onscreen, but judicious use of Silver Efex certainly can create a remarkably ‘film-like’ look. In the above instance, the diffuse natural light works to narrow the distance between the two as digital’s Achilles heel – blown highlights – isn’t in issue.

Can you tell which is which?

One thing to keep in mind, regarding articles about film-versus-digital resolution: They inevitably compare digital images to scanned film. Apples and oranges, really. Scanning of film is a great convenience, but it brings an entire extra technology into the loop.

One thing to keep in mind, regarding articles about film-versus-digital resolution: They inevitably compare digital images to scanned film. Apples and oranges, really. Scanning is a great convenience, but it brings an entire extra technology into the loo

A Leica M6 and Tri-X v. the Leica Monochrom

An interesting comparison of 35mm Tri-X shot with an M6 versus the digital Monochrom, identical subjects, identical lenses, by French photographer Alexandre Maller (www.alexandremaller.com) posted on summilux.net. All photographs are by Mr. Maller.

3 lenses used: -. Summicron 35 asph – Summicron 50 V – Apo-Summicron 90 asph.

Silver images: Tri-X exposed at ISO 400 and developed in Ilford LC 29-1. The negatives were then scanned at 3200 DPI original size with an Epson V700,.

Digital images: 400 ISO DNG , then post processed in Adobe Camera RAW 6.6.

In resolution and detail the digital files are superior, but I prefer the rendering and the particular dynamics of the film – the rendering from highlights to shadows and grain distribution over various tones looks more pleasing to the eye, fuller, warmer, less ‘plasticky’ even looking at limited web-sized pictures. After over a decade of rapid development in digital capture the best digital engineers still haven’t mastered the art of digital film emulation. The clinical digital sterility is still there with the Monochrom, especially seen on mid tones and highlights. To achieve the look of film with the Monochrom, which is what Leica purports it to do, you’d need to add digital grain to certain midtones, soften highlights (often impossible with digital files because they’re clipped), and expand the shadows.

Tri-X (Above). Monochrom (Below)

Tri-X (Above). Monochrom (Below)

Tri-X (Above). Monochrom (Below)

Tri-X (Above). Monochrom (Below)

Which leads to the obvious question: why spend $7500 on a digital camera that emulates the “film look” when you can just buy a used Leica M film camera for $1000 and a 100′ roll of Tri-X and get the real thing? And another thing to think about: in 50 years that M4 you buy on Ebay for $950 will still be working just fine, no batteries needed, while your Monochrom will have been consigned to the junk heap decades ago.

The M4, all parts made by Leitz, is all mechanical, all parts capable of being replaced without much ado by a competent repairman or machinist. The MM (and all digital ‘cameras’) are consumer electronic commodities meant to be replaced by newer, “better” commodities every three years or so. Your Monochrom employs specialized chips and other parts, not made by Leica and therefore out of their control, which exist in finite supply: a proprietary shape and voltage battery manufactured by a third party, proprietary code to run itself, a proprietary imaging chip. Your Leica MM also depends on a host of other third-party technology (e.g. computers, image processing programs, web browsers) over which neither Leica nor you have any control. In 15 years, while your M4 loaded with Tri-X sits happily on your shelf next to book binders full of sleeved negatives you can touch and manipulate at your leisure, your Monochrom, all electronics and tiny motors, will be unrepairable because there won’t be parts. And good luck finding and/or retrieving all your MM DNG files.

Gianni Berengo Gardin Talks About His Love of Film Leicas

Gianni Berengo Gardin is an Italian photographer who has worked for Le Figaro and Time Magazine. Considered a artistic heir to Henri Cartier-Bresson, like Bresson he has long used and admired Leica rangefinders. His work has been published in more than 200 photographic books and shown in the most prestigious galleries and museums around the world, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Now 82, Gardin boasts a personal archive of more than a million pictures.

Q. How long have you used a Leica? A. Always: although in the fifties I used a Rolleiflex 6×6 because the clients preferred medium format to the smaller, 35 mm film, but I always had a Leica III in my bag for my own use. Then in 1954, when Leica released the revolutionary model “M” bayonet, I was among the first in Italy to buy it in a shop in Venice, where I lived. I had to pay for it in installments because German quality has always been expensive here in Italy. Since then I’ve owned and used, in order, an M2, M4, M6 and M7, and I still continue to use my M7 as my primary camera, even today.

Q. It is still worth spending a significant amount on a simple Leica rangefinder when the market offers all kinds of models with all kinds of features at prices far more competitive? A. In the 50’s, the excellence of a Leica camera was clear. Today, the high level of optical and mechanical reliability remain, although the qualitative gap compared to other brands has narrowed. However, what remains important for me is the tradition of Leica. I feel a responsibility when I use my Leica, a responsibility to carry on the great photographic tradition of photographers from Dorothea Lange to Henri Cartier-Bresson, Eugene Smith, Josef Koudelka.

Q. You still prefer the film: Why? A. I trust its archival properties. I’m afraid that digital capture, without a physical medium, can not be sustainable over time.

Q. Have you tried a digital Leica? A. Yes I’ve used a digital Leica. The quality is excellent and it certainly gives you the advantage of flexibility and speed, but for my type of work its not so important to see the result immediately. It is said that older men are attracted to younger women: for photography, for me its the opposite. Instead of looking for the latest model I an romantically faithful to the classic models of the past. In my bag there will always be three film camera bodies and two wide-angles – a 35 mm and 28 – always allowing me to be close to my subjects.

The Tri-X Factor

Bryan Appleyard, From INTELLIGENT LIFE magazine, March/April 2014

Kodak’s Tri-X is the film the great photographers love. When Kodak started collapsing—finally filing for bankruptcy in January 2012—some of the greatest photographers in the world panicked. Don McCullin immediately ordered 150 rolls of Kodak’s Tri-X black-and-white film. “I rang up my stockist and asked for them right away. I thought it was the end of my life. I don’t even know if they are still making it.”

Relax, Don, they are. After the company emerged from bankruptcy, a new company, Kodak Alaris, took over film production and, so far, it seems committed to producing Tri-X. But don’t relax too much. You are going to have to shoot those rolls pretty soon. Films, unlike digital sensors, have to be cared for. They need to be stored in fridges and even then, like supermarket food, they have expiry dates. This did not deter Anton Corbijn, the photographer and film-maker, from panic buying on a far larger scale than McCullin.

“I bought 2,500 rolls. My studio in Holland has three floors and there’s a fridge on each floor, all full of Tri-X. They must all be near their expiry date now. I don’t know what to do.”

McCullin shoots Tri-X alongside digital. Corbijn shoots almost nothing but film, Tri-X for black-and-white and Kodak Portra for colour. They are veterans—McCullin is 78 and Corbijn 58—but they are not Luddites and they are not wallowing in nostalgia. They are intent on preserving an artefact, a practice and an art form that, they say, simply cannot be matched by the technologies of digital photography. They are also keeping alive a cultural moment defined by one brand of film.

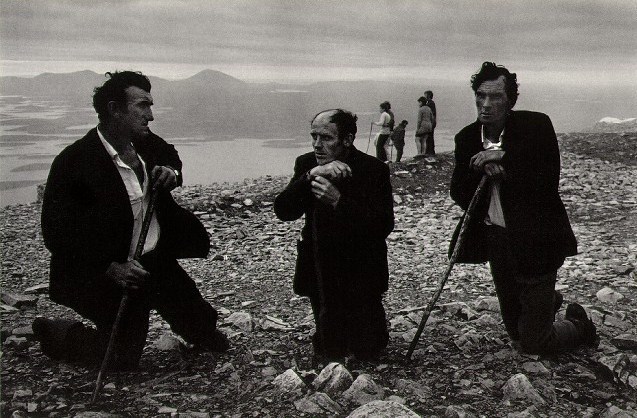

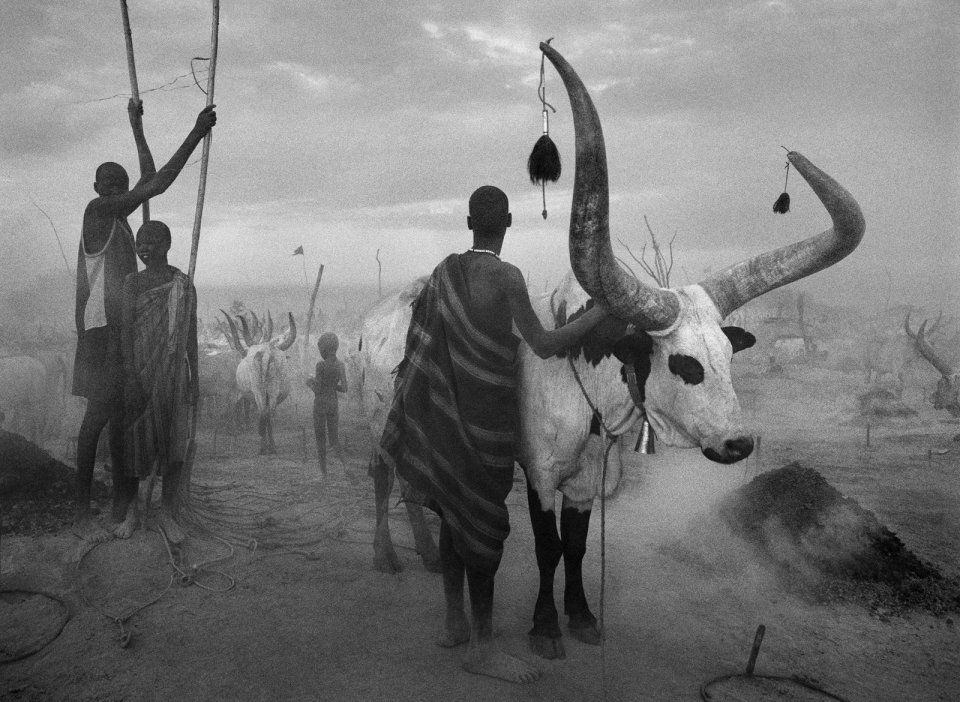

It was on Tri-X that McCullin captured some of the most powerful images of the Vietnam war: the shell-shocked American soldier with the thousand-yard stare and the fallen Vietamese soldier with bullets and family snaps scattered about him. It was on Tri-X that Corbijn took some of the greatest rock’n’roll photographs, including his documentation of the capering genius of Tom Waits, which has now run for nearly 40 years. In fact, if we include just a few other Tri-X users—Henri Cartier-Bresson, Garry Winogrand, Alfred Eisenstaedt, Irving Penn, Richard Avedon, Josef Koudelka and most of the finest of the photographers who worked for the Magnum agency—it becomes clear that this film may be the most aesthetically important technology in photographic history. The story of Tri-X is unique. It goes to the heart of how we see and what we see and what we may be losing as billions of casual, digital snaps are taken daily and as photographic integrity is subverted by the dead, flawless, retouched faces of actors and models that gaze blankly out at us.

As a commercial product, Tri-X is 60 this year. It first appeared in 1940, but only as a sheet film for large-format cameras. In 1954 it was released as a roll film for 35mm and medium-format cameras. In effect, it launched the golden age of black-and-white photography that was to last until the 1980s, as well as a new, urgent style of newspaper and magazine photography. It did so, first, through a simple technological innovation. Films are rated by their sensitivity, measured by what used to be called an ASA number, now known as ISO. The higher the number, the more sensitive (“faster” in photo-jargon) the film—or sensor—is to light, though the cost of high sensitivity may be an increase in grain or “noise” in the image. Tri-X was rated at 400 ASA, very fast for its time (modern digital cameras can go up to 26,000 or more). But it was also flexible and forgiving. Even if your exposure was slightly wrong, you could still get a decent shot and Tri-X could easily be manipulated in the darkroom—it became common chemically to push its ISO up to 800 or 1,600. Faster, more flexible film meant that professionals could now use the same film for outdoor and indoor shots and amateurs could be reasonably sure that their pictures would come out.

“I was technically awful when I started out,” says Sheila Rock, a photographer who made her name with shots of London punks in the 1970s. “I used to wonder if my images would come out, but with Tri-X they did.”

“Tri-X allowed me to make mistakes, of which there were many over the years,” Corbijn says, “and I somehow always got a print out of it.”

The more important innovation, however, was aesthetic. It is hard to describe exactly the look of a Tri-X picture. Words like “grainy” and “contrasty” capture something of the effect, but there is more, something to do with the obsidian blacks produced by the film and with a certain unique drama that made the rock photography of the Sixties and Seventies so powerful and distinctive. Steve Schofield, a British photographer, now in Los Angeles, who first encountered Tri-X in the Seventies, has a different word: “I got these incredibly contrasty negatives that still somehow managed to render detail in both the shadows and highlights. It’s got that steely look, not warm like lots of other film bases. It’s that basic look from Tri-X that I’ve tried to incorporate into my work which is now mostly shot digitally and is now colour…that monochromatic palette, but interpreting it with a simple colour base. If I do ever need to shoot black-and-white, I always prefer film and always opt for Tri-X.”

Another good word is “dirty”. In the early 1950s, monochrome photography was still dominated by the pearly perfection that came in with the black-and-white films of the Thirties. Those pictures had a wide tonal range—many shades of grey—but they tended to look flat. Tri-X, with its narrower tonal range, seldom looked flat and its harder, steelier style fitted the mood first of the realism of the Fifties, then of the casual, go anywhere, do anything mood of the Sixties. This dirtiness—a product both of Tri-X’s grain and its ability to work in low light—was the photographic correlative of three movements in other art forms: the Angry Young Men in literature, the School of London in painting, and the socially engaged work of Lindsay Anderson and Tony Richardson in the cinema. It was an aspect of an age that rejected the cosy, the safe and the merely glamorous in favour of the dynamic, the unstable and the pungent smell of lived life. From this emerged, in the Seventies, Anton Corbijn, perhaps the supreme artist of dirty Tri-X. In his early work, the dirtiness was intensified in the processing and the result was stark, imperfect shots with very visible grain that felt more realistic than any perfectly developed and processed shot.

“Grain is life,” Corbijn says, “there’s all this striving for perfection with digital stuff. Striving is fine, but getting there is not great. I want a sense of the human and that is what breathes life into a picture. For me, imperfection is perfection.”

The urgency of its images made Tri-X the first choice of reportage photographers, from great artists like Cartier-Bresson and McCullin down to the snappers on the local paper. All you needed was a Nikon F camera—expensive but tough and absurdly easy to use compared with today’s professional cameras—and a few rolls of Tri-X and, maybe, a darkroom in your bathroom, and suddenly you could call yourself a photographer.

It should be said that there may have been some magical thinking in all this. Tri-X produced brand loyalty that produced superstitious devotion. Though it was the first fast black-and-white film, it was not on its own for long. Ilford produced a competing 400 ISO film that many regarded as interchangeable with Tri-X and, in any case, long before Photoshop came along, the great darkroom craftsmen could do almost anything with printing and processing. “We could always do what you wanted in the darkroom,” says Mike Spry, a printer at the firm Downtown Darkroom who handled the films of David Bailey, Patrick Lichfield and Anthony Armstrong-Jones (Snowdon). “The great thing about black-and-white as opposed to colour was that you could change things around.”

Though it is true to say that professional digital photography of the face has converged on the dead, waxy, heavily retouched style that dominates the glossy magazines, it should also be remembered that good old-fashioned darkroom technique also involved extensive retouching. The finished product was different but no less manipulated.

Nevertheless, it was Tri-X that created the possibility and then the demand for urgency, contrast, grain and drama in photography. It revitalised photography as a whole, but black-and-white photography in particular. In doing so it drew attention to the fact that, in spite of the incursion of colour and all the billions of hues and shades of digital, there remains something natural and true about the monochrome photograph, something that springs directly from the camera itself. Sebastião Salgado refuses to consider colour—he regards it as an offensive distraction—and has had his Canon digital cameras adapted so that the screen on the back shows only black-and-white.

It was also thanks to Tri-X that the wave of grainy, dirty reportage pictures changed high art photography. Art photography in the Sixties and Seventies, even in high fashion, was all about dirty grainy realism—and, of course, black-and-white.

“They were great times for printers like me,” Mike Spry says. “Just as hairdressing became an art form in those days, so did black-and-white photography.”

Corbijn’s doctrine that grain is life expresses a great truth about the Sixties and Seventies way of seeing the world. The age was defined by a rebellion against safe perfection and a quest for truth in experimentation, danger and dirt. Nothing captured this moment better than Michelangelo Antonioni’s extraordinary film “Blow-Up” (1966). A Bailey-like photographer called Thomas, played by David Hemmings, makes extreme blow-ups of some monochrome shots he has taken in a park and discovers, emerging ghost-like from the grain, a corpse. But the truth of this corpse—he returns to the park to check that it is really there—contrasts with the bright, high-resolution, high-colour, hallucinated and erotic fantasies of Swinging London. In the end, Thomas is seduced by the unreal. He turns away from the truth of the grain and embraces grainless hippie unreality, a choice symbolised by his willingness to retrieve a non-existent tennis ball. It is hard to imagine a more vivid statement of the legacy of Tri-X and of its centrality not just as a film but as an idea of the age.

In the late 1990s Sebastião Salgado faced a crisis. Ever since the 1960s he had been shooting Tri-X, but he was not sure he could go on—either as a Tri-X user or even as a photographer. He specialises in long, heroic expeditions to produce his astounding pictures, most familiarly of the effects of industry on the third world. As airport security tightened, up to and after 9/11, he found it harder to persuade officials that his cases containing hundreds of rolls of film should be spared the X-ray machines. The signs say these machines do not affect film, but Salgado insists they do, especially if, like him, you pass through six or seven airports in a single trip. “The grain”, he says, “loses its structure.” The people at Kodak, meanwhile, have passed Tri-X through X-ray machines many times and they insist that it is not affected. Salgado, and many other pros, remain unconvinced.

His career and his next great work, “Genesis”, were saved by Canon. They claimed their latest digital cameras could match the quality of film and, after testing in the early 2000s, Salgado agreed. He now shoots everything on digital. Yet this is still a contentious point. Some say it is a simple matter of how many pixels can be packed on a sensor. Film photography, as an analogue form, produces pictures by allowing light to fall on chemically coated celluloid, creating an analogue of the scene in front of the lens. Digital, in contrast, collects light through a series of tiny sensors and then creates an electronic copy of the image. Film has very high resolution and early digital cameras with, say, 5 megapixels—5m sensor points—could not match this. This does not mean their photographs were less realistic, just that they could not be blown up beyond a certain native size without breaking down. For professionals, this makes cropping a digital photograph very costly in terms of available resolution, though software is available that interpolates additional pixels by working out what would be there if the resolution were much higher. Pixel counts have been rising steadily, and both Sony and Nikon now offer cameras for less than £2,000 that deliver 36 megapixels, a level of resolution that probably exceeds the capability of any 35mm film.

But, of course, it is not that simple. Squashing ever more pixels on to a sensor makes for technical problems and, in any case, it may not be the point. Film versus digital, McCullin points out, is still a debate among professionals and they are not talking about megapixels. Film is about more than just resolution, it is about authenticity. Film has other, more mysterious qualities.

“Film has more depth,” Sheila Rock says, “it’s the depth of going into a picture which I don’t find with digital. It’s much flatter. Some say it’s getting much better and I do see some things that have impressed me.”

Salgado knew this and he wasn’t quite prepared to go all the way to the digital look. He still wanted his all black-and-white pictures to look like Tri-X—and they do.

“I went to the exhibition of ‘Genesis’ at the Natural History Museum,” Rock says. “I looked really closely at the pictures and I thought they were Tri-X, but I was told they were digital prints.”

When I asked Salgado how this was done, he shrugged. He did not know: all he did know is that his technicians could produce the Tri-X look he liked. He never touches a computer and his post-production work is done by assistants at his studio in Paris. In fact, and this is a sign of the image-making times, many widely available digital photo-editing programmes now offer “film emulation”. You can simply scroll through a list and pick which type of film you want. Click on Tri-X and your picture will instantly be transformed—grain, drama, dirt and all. It works very—to devotees, alarmingly—well.

This software trickery, inserted into the digital algorithms to mimic an old manual craft, is another symptom of the now familiar phenomenon of analogue defiance, a rebellious hunger for the pre-digital world. Sales of vinyl records are now going up again, resistance to e-books can be fierce and, in New York, an art magazine called Master Cactus has emerged, which is only available on a tape cassette. In photography, the company Lomography has carved out an odd little niche market for plastic and toy film cameras whose dodgy construction produces bizarre and unpredictable effects. Polaroid cameras are on sale again and Fujifilm has produced its own version of instant snappery with the Fuji Instax film. Online, the 100m-plus users of Instagram can apply filters to give their pictures a variety of retro, filmish looks. People seem to be perversely drawn to the shortcomings of film photography—the light leaks of Lomography’s toy cameras, the strange starkness of small Polaroids and even, on Instagram, the corner-vignetting produced by vintage lenses.

Analogue defiance is a real and increasing force in the marketplace. It may be converting only a few to all the hassle and artistry of film, but, as a symbolic statement, it has had enormous impact on camera design. Film cameras, even the most expensive, were simplicity itself with only, in essence, three controls—focus, aperture and shutter speed. Professional or “prosumer” digital cameras have so many controls, it is impossible to list them all. And they are operated by a very user-unfriendly set of buttons. These were discouraging amateurs from trading up, so over the past few years manufacturers, led by Fuji with its X range, have been making retro-looking cameras with old-fashioned wheels and switches. This was so successful that even Nikon, one of the big makers of professional digital cameras, went so far as to produce the Df, a digital camera designed to look like the old Nikon F on which so much Tri-X was shot. It is an absurd and ungainly product costing over £2,700, which, by my reckoning, means you are paying at least £1,000 for the knurled metal knobs on top.

If that all represents a 180-degree turn away from digital perfection, some have gone even further, rejecting the perfect via a kind of 360-degree turn. Google Street View famously, notoriously, set out to photograph all the streets in the world using car-borne digital cameras. Two artists, Michael Wolf and Jon Rafman, decided to use selected images from the millions thus produced to create eerie works of art. These were technically poor photographs, but evocative nonetheless. It was, in its way, an attempt to resurrect the art of street photography, an art taken to a very high level with Tri-X in the hands of photographers like Winogrand and Cartier-Bresson. In their day, street photography was welcomed and safe; now it is dangerous—you can get accused of paedophilia, suspected of being some kind of snooper or, by police, of being a potential terrorist. Even worse, some of your subjects will know all about image rights and release contracts. Street View seemed to solve the problem.

But it was nothing to do with film and most of the analoguesque software gizmos are strictly for amateurs. So the question now becomes: if it can be done digitally right up to the standards required by Salgado, is there any point to Tri-X? Is there any point to film?

There is an old slogan among reportage photographers: “F8 and be there”. F8 is usually the optimum aperture on the lens, the setting that gives the best performance and is most likely to get the shot. “Be there” is just about the absolute necessity of your physical presence at the action. It is the necessity that overrides and underpins all others, so when, in 1948, Cartier-Bresson rushed to take a picture of Nehru announcing the assassination of Gandhi, it did not matter that it was out of focus, ill-lit and streaked with lens flares; all that mattered was that Cartier-Bresson was there to pluck something, anything, from the chaos of events. And, of course, he plucked a masterpiece.

It is this existential truth of photography that professional film-users fear is being lost in the increasingly virtual digital world. “Film is honest,” says Sheila Rock, summarising the views of them all, “Tri-X is honest.” Dishonesty, in this context, can be seen on any newsstand. The business of digital retouching is dictated by the demands of the American star system. Rock, who is obliged to use digital for commercial work, was even told by one client in response to her tastefully retouched images that “American women like to be more perfect”. The result is a universal digital convergence on a style that makes the stars of the covers look like Stepford Wives, robotic and impersonal—they might all be Jennifer Aniston or they might not, it does not matter. Anton Corbijn recently got one of his Tri-X shots into a glossy, but not until they’d asked him if it could be done in colour. He explained that, with film, the shutter click is terminal, at least in this respect.

Corbijn is regarded with envy and awe by many of his peers, but he does not call himself a professional—“there is so much I don’t know”—and he believes in the power of limitation to increase your creativity. This is why he sticks to film: it does not have the vast flexibility of digital, a flexibility that detracts from the power of the moment when the shutter fires. He is passionate about the material process of making a photograph from film.

“When I started, I felt that I didn’t want a normal job in photography, I wanted that sense of adventure when you meet someone and take a picture. I felt that digital is more like a job. You look at the screen to see if you have it right, then you take another picture. When I come back from a trip, I don’t know what I have exactly. I have to get it developed, so I won’t know for a couple of days. I like the tension of not knowing exactly what you have.”

“There’s nothing like going to Vietnam,” says McCullin, echoing the thought, “when I had to sit on the film for six weeks with a mental memory of the images I took. I had to be patient and carry all that film back to England. It became more precious by the week. And then you went to the lab wondering whether what you had was as good as what you thought you had. The waiting and the torment gave an edge to the whole procedure. Now, with digital cameras, you are looking at the screen on the back after every shot. It becomes an instant thing like fast food, it takes something away from the original menu.”

On top of that thrilling anguish, there is the manual craft of the darkroom where either the photographer himself or his trusted technician would use a bewildering array of methods—“ducking and weaving with bits of wire and stuff,” McCullin says—to manoeuvre the image as close as possible to the one in the artist’s head.

All this is being lost as darkrooms close and companies stop producing one type of film after another. Of course, many things are gained, but the full cost of digitalization in many fields, not just photography, is yet to be accounted. Kodak say that film in general and Tri-X in particular is safe. Yet I felt a pang when I asked how they were going to celebrate the diamond jubilee of their greatest film, and they said they had “no definitive plans we can share as of today”.

Never mind, we can do it for them by remembering Tri-X’s black-and-white golden age and celebrating its continuation in the works of Salgado, Rock, Corbijn and, of course, McCullin, the old master. He was off to India when we spoke.

“An Indian dawn with Tri-X,” he said, “it’s like being in heaven.”

Happy birthday, Tri-X, and many more of them.

Robert Frank Gets Arrested Down South

In November 1955, Lt RE Brown of the Arkansas State Police spotted an unshaven and shabbily dressed suspicious looking man driving an old Ford near the Mississippi River.The man’s car was full of maps, numerous papers written in foreign languages, and a number of strange German “Leica’ cameras with bags and bags of exposed films. Suspecting the man to be a communist spy, Lt Brown arrested Robert Frank and brought him to the McGehee City jail for fingerprinting and interrogation. A local citizen “who knew several foreign languages” was brought in to assist in Frank’s questioning even though Frank spoke fluent English.

The Swiss-born Frank protested that he was a professional photographer who had received a grant to travel America taking pictures. He explained that his work had been published in the New York Herald Tribune, the New York Times and Life and Look magazines. Frank showed the Lt. some of his work, what looked to Lt. Brown like spy photos: blurry images, often out of car windows, of things like bridges, factories and power stations. It was only when Frank produced a well worn copy of Forbes magazine with his name and photos prominently displayed was he finally allowed to go on his way. His fingerprints were forwarded to the FBI.

Four years later, in 1959, some of the same pictures he showed Lt Brown would be published in book form in Frank’s seminal work The Americans.

ARKANSAS STATE POLICE

Little Rock, Arkansas

December 19, 1955

Alan R. Templeton, Captain

Criminal Investigations Division

Arkansas State Police

Little Rock, Arkansas

Dear Captain Templeton:

On or about November 7, I was enroute to Dermott to attend to some business and about 2 o’clock I observed a 1950 or 1951 Ford with New York license, driven by a subject later identified as Robert Frank of New York City.

After stopping the car I noticed that he was shabbily dressed, needed a shave and a haircut, also a bath. Subject talked with a foreign accent. I talked to the subject a few minutes and looked into the car where I noticed it was heavily loaded with suitcases, trunks and a number of cameras.

Due to the fact that it was necessary for me to report to Dermott immediately, I placed the subject in the City Jail in McGehee until such time that I could return and check him out.

After returning from Dermott I questioned this subject. He was very uncooperative and had a tendency to be “smart-elecky” in answering questions. Present during the questioning was Trooper Buren Jackson and Officer Ernest Crook of the McGehee Police Department.

We were advised that a Mr. Mercer Woolf of McGehee, who had some experience in counter-intelligence work during World War II and could read and speak several foreign languages, would be available to assist us in checking out this subject. Subject had numerous papers in foreign langauges, including a passport that did not include his picture.

This officer investigated this subject due to the man’s appearance, the fact that he was a foreigner and had in his possession cameras and felt that the subject should be checked out as we are continually being advised to watch out for any persons illegally in this country possibly in the emply of some unfriendly foreign power and the possibility of Communist affiliations.

Subject was fingerprinted in the normal routine of police investigation; one card being sent to Arkansas State Police Headquarters and one card to the Federal Bureau of Investigation in Washington.

Respectfully submitted,

Lieutenant R.E. Brown, Lieutenant Comanding

Troop #5

ARKANSAS STATE POLICE

Warren, Arkansas

“Leica Photography” Is Dead. Leica Killed It.

Above are two of my favorite photographs from two of the twentieth century’s most skilled and creative photographers. Both are powerfully evocative while being deceptively banal, commonplace. A dog in a park; a couple with their child at the beach. Both were taken with simple Leica 35mm film cameras and epitomize the traditional Leica aesthetic: quick glimpses of lived life taken with a small, discrete camera, what’s come to be known rather tritely as the “Decisive Moment.”

Looking at them I’m reminded that a definition of photographic “quality” is meaningless unless we can define what make photographs evocative. In the digital age, with an enormous emphasis on detail and precision, most people use resolution as their only standard. Bewitched by technology, digital photographers have fetishized sharpness and detail.

Before digital, a photographer would choose a film format and film that fit the constraints of necessity. Photographers used Leica rangefinders because they were small, and light and offered a full system of lenses and accessories. Leitz optics were no better than its competitor Zeiss, and often not as good as the upstart Nikkor optics discovered by photojournalists during the Korean War. The old 50/2 Leitz Summars and Summitars were markedly inferior to the Zeiss Jena 50/1.5 or the 50/2 Nikkor. The 85/2 and 105/2.5 Nikkors were much better than the 90/2 first version Summicron; the Leitz 50/1.5 Summarit, a coated version of the prewar Xenon, was less sharp than the Nikkor 50/1.4 and the Nikkor’s design predecessor the Zeiss 50/1.5. The W-Nikkor 3.5cm 1.8 blew the 35mm Leitz offerings out of the water, and the LTM version remains, 60 years later, one of the best 35mm lenses ever made for a Leica.

But the point is this: back when HCB and Robert Frank carried a Leica rangefinder, nobody much cared if a 35mm negative was grainy or tack sharp. If it was good enough it made the cover of Life or Look Magazine. The average newspaper photo, rarely larger than 4×5, was printed by letterpress using a relatively coarse halftone screen on pulp paper, certainly not a situation requiring a super sharp lens. As for prints, HCB left the developing and printing to others, masters like my friend and mentor Georges Fèvre of PICTO/Paris, who could magically turn a mediocre negative into a stunning print in the darkroom.

50’s era films were grainy, another reason not to shoot a small negative. Enthusiasts used a 6×6 TLR if they needed 11×14 or larger prints. For a commercial product shot for a magazine spread the choice might be 6×6, 6×7, or 6×9. Many didn’t shoot less than 4×5. If you wanted as much detail as possible, then you would shoot sheet film: 4×5, 5×7 or 8×10.

What made the ‘Leica mystique’, the reason why people like Jacques Lartigue, Robert Capa, HCB, Josef Koudelka, Robert Frank and Andre Kertesz used a Leica, was because it was the smallest, lightest, best built and most functional 35mm camera system then available. It wasn’t about the lenses. Many, including Robert Frank, used Zeiss, Nikkor or Canon lenses on their Leicas. It was only in the 1990’s, with the ownership change from the Leitz family to Leica GmbH, that Leica reinvented itself as a premier optical manufacturer. The traditional rangefinder business came along for the ride, but Leica technology became focused on optical design. Today, by all accounts, Leica makes the finest photographic optics in the world, with prices to match.

Which leads me to note the confused and contradictory soap boxes current digital Leicaphiles too often find themselves standing on. Invariably, they drone on about the uncompromising standards of the optics, while simultaneously dumbing down their files post-production to give the look of a vintage Summarit and Tri-X pushed to 1600 iso. Leica themselves seem to have fallen for the confusion as well. They’ve marketed the MM (Monochrom) as an unsurpassed tool to produce the subtle tonal gradations of the best B&W, but then bundle it with Silver Efex Pro software to encourage users to recreate the grainy, contrasty look of 35mm Tri-X. The current Leica – Leica GmbH – seems content to trade on Leica’s heritage while having turned its back on what made Leica famous: simplicity and ease of use. Instead, they now cynically produce and market status.

For the greats who made Leica’s name – HCB, Robert Frank, Josef Koudelka – it had nothing to do with status. It was all about an eye, and a camera discreet enough to service it. They were there, with a camera that allowed them access, and they had the vision to take that shot, at that time, and to subsequently find it in a contact sheet. That was “Leica Photography.” It wasn’t about sharpness or resolution, or aspherical elements, or creamy bokeh or chromatic aberration or back focus or all the other nonsense we feel necessary to value when we fail to acknowledge the poverty of our vision.

When Was The Last Time You CLA’d That Thing?

Perusing an online auction site this morning I came across a Leica X1 offered for sale. The seller informed potential buyers that the camera had recently received a “CLA (Clean, Lubricate, Adjust)”. The obvious question in need of asking is this: why would anyone think that a 3 year old fully electronic camera would need a “CLA”? What would you “clean, lubricate and adjust”? I presume the camera could be sent for a sensor cleaning, although the X1 is a fixed lens compact whose sensor is fully sealed and opening it up would seem to be counterproductive if your intent is to shield the sensor from ambient dust. As for “lubrication and adjustment,” well, I’m stumped, which started me thinking, again, about the irrationality of many of us who love Leicas.

Pictured above are two of my cameras. They both were manufactured over 50 years ago. Both are fully mechanical; no battery needed. Both are “users” in the parlance of camera collectors, although the M2 looks significantly less worn than the Nikon. The Nikon started its life as a working camera for a major newspaper. (Somewhere I have a photo, taken with this exact camera, of Muhammad Ali standing victorious over Sonny Liston on May 25, 1965 in Lewiston, Maine, taken by Don Rice for the New York Herald Tribune.)

The Nikon has never been serviced. It probably never will. I can’t see what the purpose would be. The shutter fires; the slow speeds sound right, the film winds on without complaint. The camera has no light leaks. There’s a little dust in the finder, but hey, what SLR doesn’t have a little dust in the finder? With its 50mm 1.4 Nikkor attached it produces beautiful negatives indistinguishable from those from the M2. It’s only stopped working once, a few years back. The shutter jammed. After diagnosing the problem, I gave the camera a sharp whack against my workbench, and the shutter started working again. It’s worked fine since. If I ever sell it (doubtful though that be), no one will ask me if its been “CLA’d”.

My M2 was recently sent out for a “CLA.” The viewfinder front window had some haze on its inside and I wanted it clean and clear. A simple fix. But, while it was in for service, I figured it might as well be “CLA’d”. It still had its L seal, meaning it had probably never been serviced before, so it couldn’t hurt. Plus, I’d have documentation of its bonafides in case I ever wanted to sell it. It came back with a clear window and “buttery smooth” operation and calibrated shutter and official recognition that it had been serviced by Youxin Ye (a wonderfully nice man BTW and, from everything I’ve seen and heard, a superb Leica service technician).

So what if it was “buttery smooth” when I sent it in, right? Cost: $160.

The Leica MP2

This is a Leica MP2 with Wetzler Electric Motor Winder. In December, 2010 this MP2 sold at auction for €402,000.

The MP2 is a modified M2 and not a revised MP. It was produced by Leica in 2 batches – 12 in 1958 and 15 in 1959. These differed from the M2 in that it came equipped with electronics for the Wetzler Electric Motor Winder shown in the picture above. The winder coupled to the intermediate gear of the shutter. The motor grip contained the batteries that powered the motor and screwed into the base of the motor.

The MP2 shown here is one of two black MP2’s known to have been produced. The remainder were chrome.

The MP: What’s Old Is New Again

In 1956, Leica produced the MP, a “Professional” version of the M3 with long winding shaft and fitted Leicavit. Original MPs were two-stroke, and like unlike the M3, had no self-timer. The film counter was, like the M2, external and needed to be manually set. Essentially, the MP was a dual stroke M2 with 50mm viewfinder and Leicavit attached, produced a year before the introduction of the M2 in 1957. Sale of the camera was restricted to “bonafide working press photographers.” In order to purchase an MP, dealers had to specify the name, address and professional credentials of the purchasing customer. In all, Leica produced 449 cameras, 311 chrome and 138 black paint, although some existing M3’s were converted to MP’s by Leitz in the early 60’s. These conversions did not carry the MP numbering.

The MP was discontinued in 1957 after the introduction of the M2, which also used the Leicavit winder and had the advantage of a .72 viewfinder that accommodated the more popular 35mm focal length. In 2012, MP #126, shown above, sold at auction for $158,000.

In 2003, Leica introduced a “New” version of the MP with TTL exposure metering. A new Leicavit-M was offered as an accessory. The single stroke winding lever was the metal one-piece type found on the M3/MP. The viewfinder was the same version as found on the M7, and was available in 0.58, 0.72 and 0.85 magnifications, although the new black paint version was only offered with the 0.72 magnification viewfinder. Like the original MP, the top-plate was made of brass and carried the engraved Leica logo.

Leica also produced 500 “Hermes Edition” MP’s in 2003. These were chrome and covered in “Hermes Barenia calfskin.” I doubt many found their way into the hands of “bonafide working press photographers.”

Nikon’s W-Nikkor 3.5cm 1.8 – Is This The Best 35mm Wide Angle Ever Made For A Leica?

In 1956, two years after the introduction of the Nikon S2, Nikon delivered a stunning new 35mm (3.5cm) lens of 7 element 5 group design with a maximum aperture of 1:1.8. It employed rare earth Lanthanum glass to improve spherical aberration and curvature of field, enhancing both sharpness and image flatness. This Nikon mount lens used a convex shaped rear lens element larger than the front, which minimized the spherical aberration and coma problems usually associated with fast wide angle optics. It was one in a series of excellent fast optics produced by Nikon for their rangefinders, following the 8.5cm 1;1.5 in 1953 and the 5.0cm 1:1.1 in 1956. The 3.5cm 1.8 was Nikon’s shot across Leica’s bow, given Leitz’s preeminence in wide angle design, incorporating the highest technology of the period to produce optics as good, or better than, the Leitz offerings.

The W Nikkor 3.5cm 1.8 was met with rapturous reviews by Nikon photographers; almost all rated it superior to the Leitz offerings at the time, and most claimed it better than the f2 Summicron and the 2.8 Summaron both introduced by Leitz 2 years later in 1958.

Given the reception of the Nikon Mount 3.5cm, in 1957 Nikon briefly decided to offer the lens in thread mount for Leica rangefinders. While optically the same as the Nikon mount, the design of the Leica mount model is slightly different. The front element is flat, and the focusing ring is also flat without the scalloped-design on the Nikon S-Mount version. While all LTM copies are coated, Nikon omitted the “C” designation on a few hundred of the latter produced lenses. These non-designated C lenses command premium prices.

While Nikon produced 6500 of the Nikon S mount 3.5cm lens, it produced a very limited run of approximately 1500 of the Leica mount. The LTM W-Nikkor 3.5cm 1.8 exhibits extremely high resolution and high contrast in a lens faster than ƒ2. The actual resolution of this 60 year old lens is nothing short of astonishing. Even more astonishing is, that in contrast to other lenses from that era the W-Nikkor retains this kind of performance over the whole frame.The Nikon lens is so impressively good it took Leica 40 years to match its optical excellence with the $5000 Aspherical Summilux.

The W-Nikkor3.5cm 1.8 Leica mount lens was then, and remains, a rare and much sought after lens, and comes up for sale rather infrequently. If you want to try one on your Leica, if you can find one, you can expect to pay $1600-$2000 for a BGN grade copy, with prices escalating significantly for exceptional copies.

Ironic, then, that maybe the best 35mm focal length lens ever produced for the venerable Leica was made by Nikon.