[Editor’s Note: Robert Frank died yesterday, September 10, 2019, at the age of 94. IMHO, he was the most influential photographer who ever lived. This is a reprint of an article about Frank published by the New York Times in 2015]

Last May [2015], Robert Frank, the world’s pre-eminent living photographer, returned to Zurich, the orderly Swiss banking city, cosseted by lake and mountain, where he grew up. When an artist who made his reputation by leaving returns home, mixed feelings are inevitable, and that was especially true for Frank, whose iconic American pictures are notable for their deep understanding of human complication. ‘‘I know this town, but I certainly feel like a stranger here,’’ he said.

As he walked through the immaculate Zurich city center, with its many statues, gilded shop signs and fountains, Frank was ‘‘just amazed how well organized everything is, how perfect everything is.’’ The Swiss, he explained, do not throw coins into fountains, because ‘‘they have everything they need. They don’t believe in wishing wells. Only the poor have to hope.’’ Deciding he wanted to ride a streetcar, Frank surveyed the different lines. ‘‘I usually don’t get a ticket on the tram,’’ he explained. ‘‘This town is rich enough.’’ He said he never worried about being caught by inspectors, and he didn’t seem worried. He seemed the way he typically did — fully present and yet filled with personal mystery. ‘‘I don’t know where that one goes, so we’ll take it,’’ he said, and was soon bound for a working-class district of the city.

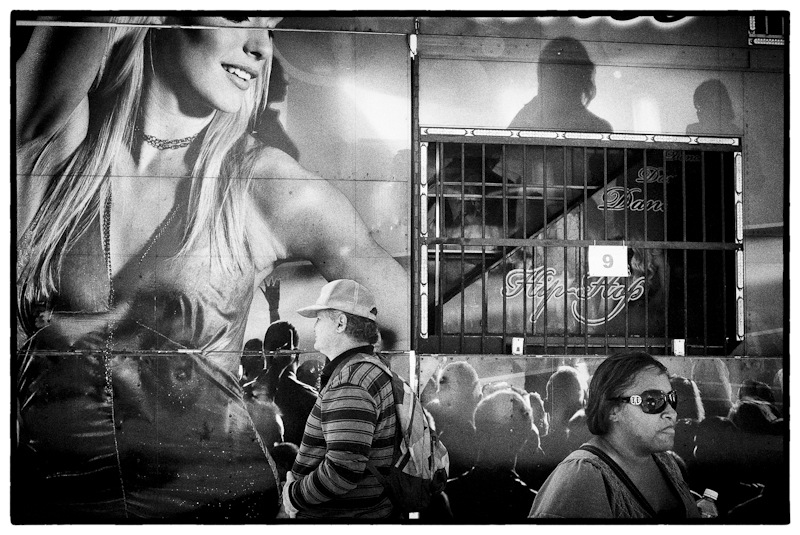

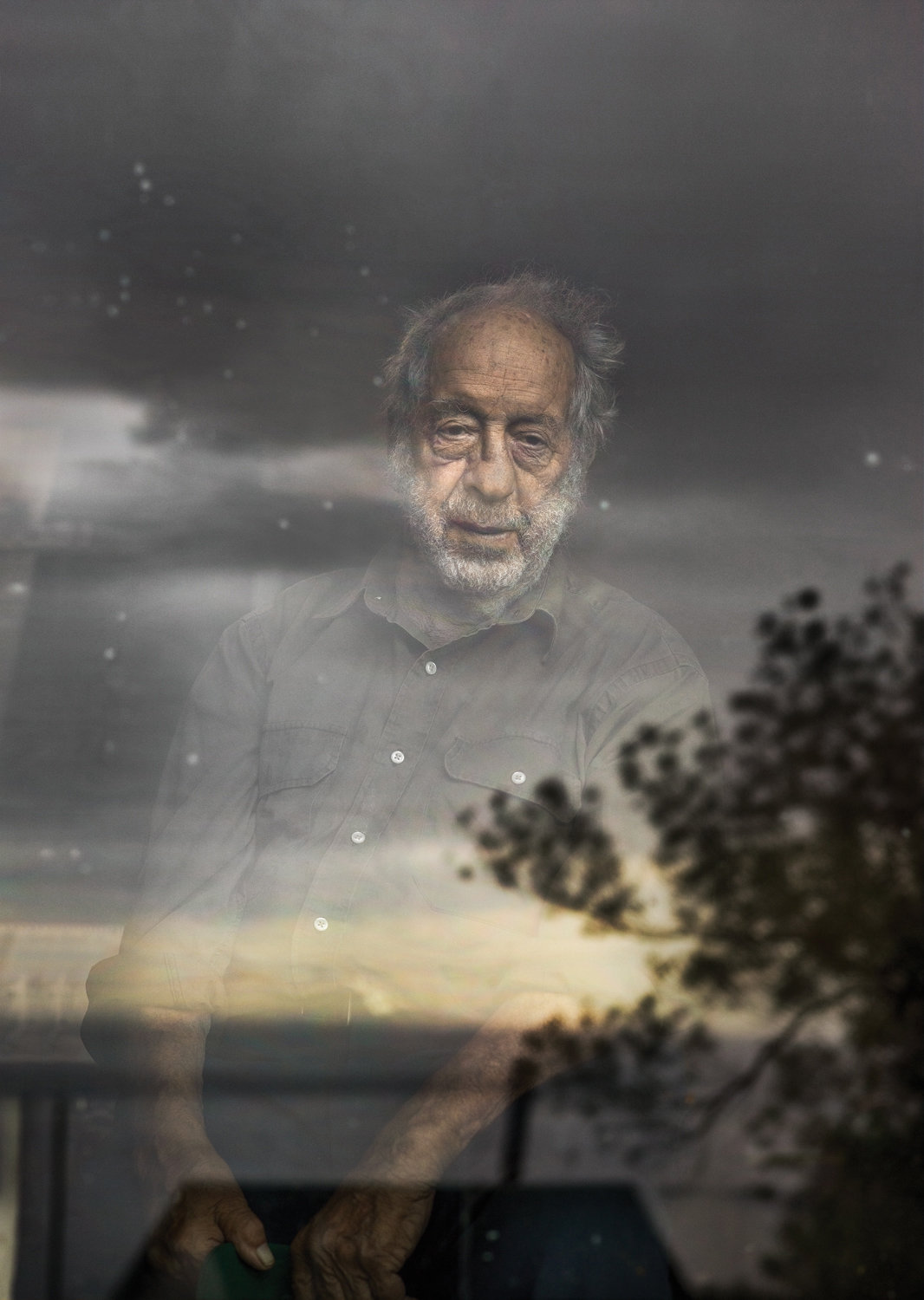

Frank has always been a picture-maker unconcerned with his own appearance, and sitting quietly beside the streetcar window, he wore the usual faded work shirt, frayed pants and one too many mornings of stubble. A sturdy man who never uses socks, a winter hat or gloves, Frank is now 90, and in the cool Swiss air, he had on a new blue down coat. His melancholy eyes rarely betray anything, but as he gazed out at the city of his youth, there was the sense of a man wary, defended, skeptical, yet willing to be engaged. In his pocket he carried an Olympus camera.

Robert Frank and June Leaf in Mabou. Credit: Katy Grannan for The New York Times

Frank had come to Switzerland to receive the Roswitha Haftmann Prize for lifetime achievement, Europe’s most lucrative fine-arts award, though he doesn’t need the money. His photographs command steep prices, and nothing about his current way of living is much different from his days as a young man, when, he says, ‘‘I decided if I swore off socks, I had more money for books.’’ Several years ago, Frank sold the paintings given to him in the 1940s by an impoverished friend, Sanyu, who became a renowned modern Chinese painter. Frank received millions of dollars, but wealth so discomfited him he used it to create a foundation and gave it away.

Acclaim was likewise anathema. By the 1960s, just as his work was gaining a following, Frank abruptly moved on from still photography to become an underground filmmaker. Ten years later, with all the glories of the art world calling to him, Frank fled New York, moving to a barren hillside far in the Canadian north. Over the years, when museums asked to exhibit his work, when universities like Yale sought to award him honorary degrees, he would think, Let someone else have it, and decline. ‘‘He never crossed over into celebrity,’’ says the photographer Nan Goldin. ‘‘He’s famous because he made a mark. He collected the world.’’

The tram entered a scruffy immigrant neighborhood not far from where Frank’s father, Hermann, had his business importing radios and record players, for which Hermann himself designed cabinets that Frank describes as ‘‘horrible.’’ Frank carried two rolls of film, but all the way out he only gazed out the window. He could have been anybody. Back in the 1950s, when Frank was making what amounted to private photographic studies in public places, one of his skills was remaining inconspicuous in casinos, restrooms and elevators. Here, near the end of the tram line, suddenly the camera appeared. There was a single click. Nothing beyond the window looked unusual. Then Frank pointed to a construction crane, its boom passing below a church steeple clock. ‘‘This is Zurich,’’ he explained. ‘‘The crane. The clock. The church. Functional.’’ It was the one picture of the day.

Sixty years ago, at the height of his powers, Frank left New York in a secondhand Ford and began the epic yearlong road trip that would become ‘‘The Americans,’’ a photographic survey of the inner life of the country that Peter Schjeldahl, art critic at The New Yorker, considers ‘‘one of the basic American masterpieces of any medium.’’ Frank hoped to express the emotional rhythms of the United States, to portray underlying realities and misgivings — how it felt to be wealthy, to be poor, to be in love, to be alone, to be young or old, to be black or white, to live along a country road or to walk a crowded sidewalk, to be overworked or sleeping in parks, to be a swaggering Southern couple or to be young and gay in New York, to be politicking or at prayer.

Robert Frank and June Leaf in Mabou. Credit: Katy Grannan for The New York Times

Robert Frank and June Leaf in Mabou. Credit: Katy Grannan for The New York Times

The book begins with a white woman at her window hidden behind a flag. That announcement — here are the American unseen — the Harvard photography historian Robin Kelsey likens to the splash of snare drum at the beginning of Bob Dylan’s ‘‘Like a Rolling Stone’’: ‘‘It flaps you right away.’’ The images that follow — a smoking industrial landscape in Butte, Mont.; a black nurse holding a porcelain-white baby or an unwatched black infant rolling off its blanket on the floor of a bar in South Carolina — were all different jolts of the same current. That is the miracle of great socially committed art: It addresses our sources of deepest unease, helps us to confront what we cannot organize or explain by making all of it unforgettable. ‘‘I think people like the book because it shows what people think about but don’t discuss,’’ Frank says. ‘‘It shows what’s on the edge of their mind.’’

On a trip upstate, Frank visited a Fourth of July celebration in rural Jay, N.Y., and photographed two girls in white dresses skipping beneath a huge, diaphanous American flag. ‘‘Something I really like is a big flag,’’ Frank says. ‘‘Here, people are so proud of it. In other countries you don’t feel they’re so proud of their flag.’’ Like most things with Frank, that cuts two ways. Foreign, uncompromisingly independent, Frank loathed the provincial prevarications of nostalgia. At closer inspection, the flag is torn, while along the photograph’s edge is the only visible face: a sneering boy. That the flag is transparent means that in ‘‘The Americans,’’ a reader looks, in effect, through the cloth to the image on the next page — to segregated New Orleans, where Frank made his best-known picture.

Frank passed through the city in 1955 and took a photograph of a row of passengers on a Canal Street trolley — whites in front, blacks in back. In the moment, life stilled into such clarity that Frank’s shutter needed to move only once. What he says attracted him then was something filmic: ‘‘Five people sitting, each occupying a frame.’’ But it’s a black man, his forehead creased, whose complex expression makes the picture. ‘‘He’s looked at that street many times,’’ Frank says. Plenty of photographs were taken during Jim Crow. Frank’s gift was to transcend reportage and tell you something about the condition — how oppression felt.

When Frank began his expedition upriver into the heart of American ambivalence, photography remained, as Walker Evans said, ‘‘a disdained medium.’’ Only a few American art museums collected photographs. Most of the published images portrayed figures of status. One notable exception was the work of Dorothea Lange. Frank respected her compassion but considered her Dust Bowl pictures maudlin — triumphalist takes on adversity. ‘‘I photographed people who were held back, who never could step over a certain line,’’ he says. ‘‘My mother asked me, ‘Why do you always take pictures of poor people?’ It wasn’t true, but my sympathies were with people who struggled. There was also my mistrust of people who made the rules.’’ That impulse seems particularly potent today, during our charged national moment — our time of belated reckoning with how violent, enraged, unbalanced and unjust the United States often still is. To look again at the photographs Frank made before Selma, Vietnam and Stonewall, before income inequality, iPhones and ‘‘I can’t breathe,’’ is to realize he recognized us before we recognized ourselves.

“Fourth of July — Jay, New York,’’ 1954, Credit: Robert Frank via Pace/MacGill Gallery

“Fourth of July — Jay, New York,’’ 1954, Credit: Robert Frank via Pace/MacGill Gallery

Frank grew up in ‘‘a sad household.’’ In the 1930s, Zurich radio was full of Hitler. ‘‘That voice cursing the Jews,’’ he says. ‘‘You couldn’t turn off the voice.’’ Hermann Frank had been an excellent Sunday photographer, but securing the material comforts of Persian carpets and fine goose liver was his priority. ‘‘My father married my mother because of money. It became the most important thing in order for them to feel good. If my father had a good day, dinner would end and my father would take out his wallet and give my mother 100 Swiss francs.’’ Frank was repelled: ‘‘I was driven by negative influence. I wanted to get away.’’

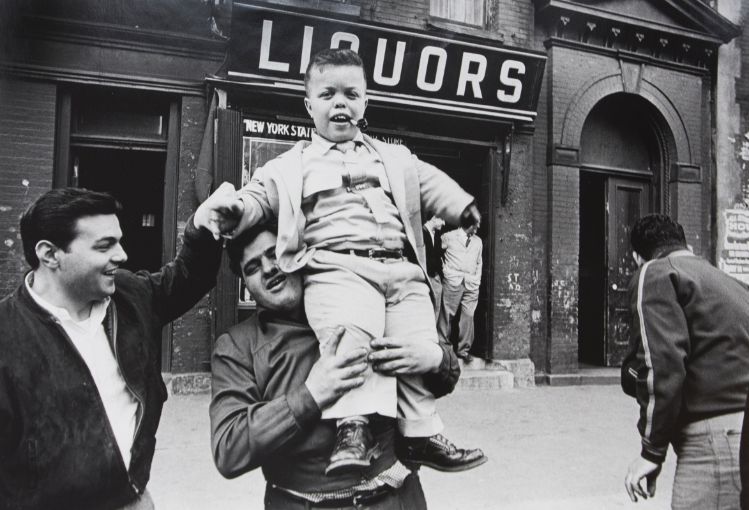

In 1947, family friends who lived in Queens met the boat that carried Frank to the United States. The next day, they showed him Times Square: ‘‘The crowd! The crowd! I never was used to such a big crowd, and they were so enthusiastic about being there. It was America! Those big signs!’’ At a coffee shop, Frank encountered a waitress who flung everyone’s silverware onto the table. In that moment of democratic informality, Frank knew New York was where he wanted to be. ‘‘In Paris you’d see African people on the subway, and they were African. Here in America they are Americans. There is no other place like this.

The sheer diversity and scale of the United States thrilled Frank. ‘‘It’s a big country,’’ he says. ‘‘Coming from Switzerland, it’s vast.’’ Because there was such freedom of mobility, he could go many places, and in all of them he saw heightened experience — including, to his surprise, the masses of people who ‘‘looked desperate.’’ Some, like him, were getting by, but for many others the American promise never took. Early on in New York he met a former soldier who ‘‘would wear his uniform from the Marines every day. Even though he was not in the Marines anymore. He asked me to rent a place with him. I did for a few months. He didn’t have a job. Nice man. Lost. They get lost.’’

Frank got commercial photography assignments from magazines like Harper’s Bazaar while also roaming around New York, following ‘‘my own feelings.’’ His way of living resisted convention —‘‘I never worried about insurance’’— as did his work. For American photographers at the time, the professional apotheosis was Life magazine. Henry Luce, the publisher, favored linear, neatly partisan narratives, and Life’s editors repeatedly rejected Frank. Frank’s photographs suggested life was more fraught: ‘‘I leave it up to you,’’ he says. ‘‘They don’t have an end or a beginning. They’re a piece of the middle.’’

Frank was also passed over by Magnum, the elite consortium of photographers led by Robert Capa: ‘‘Capa said my pictures were too horizontal, and magazines were vertical.’’ The photographer Elliott Erwitt knew Frank then and says, ‘‘It was the beginning of that kind of photography that Robert did, seemingly sloppy, but not — and very emotional. The acceptable pictures then were sharp and technically excellent. But the pictures of Robert Frank were very different.’’ To Frank, the French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson’s idea of a ‘‘decisive moment’’ in photography seemed reductive. Frank was in search of ‘‘some moment I couldn’t explain,’’ and periodically went off on his own to make pictures of Peruvian farmers, Welsh miners and French street children. His unwillingness to compromise led to breaks with friends like Erwitt. ‘‘I became a professional doing what people expected from me,’’ Erwitt says. ‘‘We all respected Robert’s talent and ability and knew he was difficult and fought with everyone — could be quite vindictive with some. We just dissolved the friendship. I felt he felt I’d gone the wrong way, the nonartist way.’’

In the late 1940s, Frank met a teenage dance and art student named Mary Lockspeiser, whose pale eyes and luminous complexion were perhaps especially compelling to a man who saw the world in black and white. ‘‘She was young, but I thought, Why not?’’ says Frank, who was nine years older. ‘‘She was alive for everything.’’ They married, and had two children: Pablo, named, he says, after the cellist Pablo Casals, and Andrea — ‘‘She was named for a boat that sank.’’ His sense of humor is just black enough that you wonder when he’s joking.

The family lived, as Mary put it in an interview with the Smithsonian Institution, ‘‘very chaotically in every way.’’ They scavenged the sidewalks for furnishings and inhabited desolate, formerly industrial downtown neighborhoods. The Franks were young artists, and struggled as parents; Pablo and Andrea were often left to themselves. ‘‘I felt we weren’t made for it,” Frank says. Mary was ‘‘a young woman who wanted to work, and I was running after my career,” he says, adding that ‘‘it was very, very hard, almost impossible to live with me.’’

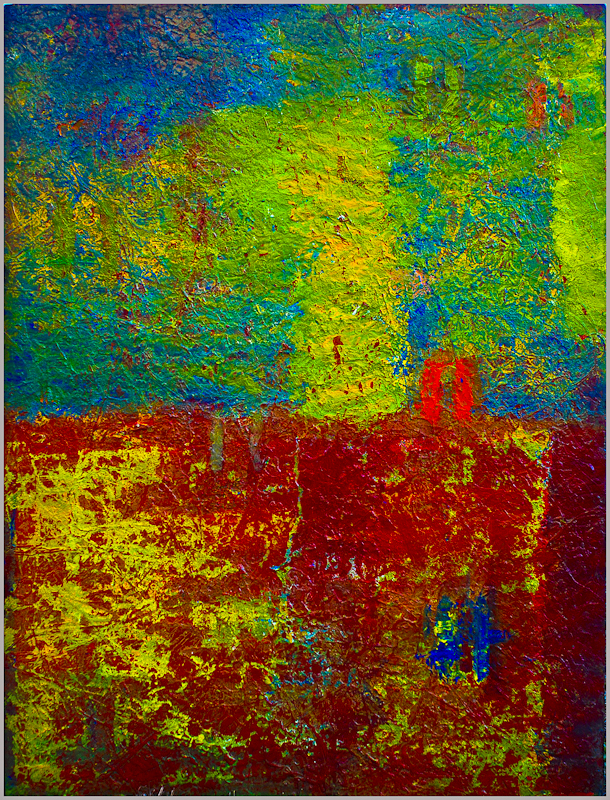

Frank absorbed artistic influences all over New York. Edward Hopper’s moody office-scapes, restaurant interiors and gas pumps were not in fashion when Frank discovered the painter: ‘‘So clear and so decisive. The human form in it. You look twice — what’s this guy waiting for? What’s he looking at? The simplicity of two facing each other. A man in a chair.’’ Frank’s creative day to day was informed by the Abstract Expressionist painters he lived among. Through his window, Frank studied Willem de Kooning pacing his studio in his underwear, pausing at his easel and then walking the floor some more. ‘‘I was a very silent unobserved watcher of this man at work. It meant a lot to me. It encouraged me to pace up and down and struggle.’’ He also saw the downside of an artist’s life: ‘‘I used to watch de Kooning work, and then I’d walk down the street and see him drinking and lying in the gutter. Somebody’s bringing him upstairs. You drink because you have doubts. Things seem to crumble around you.’’

. Robert Frank. Credit: Katy Grannan for The New York Times

. Robert Frank. Credit: Katy Grannan for The New York Times

Since there ‘‘weren’t so many artists in photography to meet,’’ Frank says, he became interested in the work of only one photographer: Walker Evans. Evans’s images of battered roadside prewar America were, as the photographer Tod Papageorge writes, Frank’s ‘‘sourcebook’’ for his own rendition of the American scene. Frank sought Evans out, and soon the older man was inviting Frank to his Upper East Side apartment to help him photograph objects like tools arranged on a table. ‘‘If I put a piece of cheese on the table and said, ‘Photograph it,’ ’’ Frank says, ‘‘his would be different from my piece of cheese. His pictures were more careful. I was fast. Hurry! Hurry! Life goes fast.’’

Evans wore English shoes and patrician airs. Frank had become close to raffish Beats like the poet Allen Ginsberg, and when Evans was hospitalized, he asked Frank not to bring ‘‘any of those friends of yours up here.’’ Frank believed that despite the humanity in his pictures, Evans ‘‘felt he was better than other people. That was something I couldn’t stand.’’

Evans admired talent, and he became Frank’s champion, encouraging him to complete a Guggenheim application to support the photographic journey that would become ‘‘The Americans.’’ Evans wrote him a recommendation, calling him ‘‘a born artist,’’ and helped plan his itinerary.

Frank left his family behind in 1955 and went off to see Miami, Los Angeles and 10,000 miles in between through the windshield of a black Ford Business Coupe. He packed two cameras, many boxes of film (kept in a bag to protect them from the sun), trunks, French brandy (‘‘Sometimes you need a little drink; it changes your attitude’’), AAA road atlases and one book, which was really a map of another kind, Evans’s ‘‘American Photographs.’’ Evans and others had suggested destinations like the Gullah communities of the south Atlantic coast, but Frank was often spontaneous.

Trolley — New Orleans,’’ 1955. The photo, part of Frank’s groundbreaking volume ‘‘The Americans,’’ was taken four days after an encounter with the police in Arkansas that darkened his artistic viewpoint. Credit: Robert Frank via Pace/MacGill Gallery

Trolley — New Orleans,’’ 1955. The photo, part of Frank’s groundbreaking volume ‘‘The Americans,’’ was taken four days after an encounter with the police in Arkansas that darkened his artistic viewpoint. Credit: Robert Frank via Pace/MacGill Gallery

The first destination was Michigan. ‘‘I went to Detroit to photograph the Ford factories, and then it was clear to me I wanted to do this. It was summer and so loud. So much noise. So much heat. It was hell. So much screaming.’’

As Frank searched for pictures, he stayed in cheap motels: ‘‘You’d always find them down by the river.’’ The first stop in a new town was usually a Woolworth’s department store. His favored shooting settings were public — sidewalks, political rallies, drive-ins, churches, parks. He wanted to find the men and women others would consider unremarkable, as well as the symbols and objects that defined them. Falling into a place-to-place rhythm, he took pictures of bystanders, vagrants, newlyweds, Christian crosses, jukeboxes, mailboxes, coffins, televisions, many cars, and those many flags.

It was an investigation, and in every frame there is pent-up atmosphere, pressure in the air, a sense of somebody’s impending exposure — maybe Frank’s. ‘‘Photography can reveal so much. It’s the invasion of the privacy of the people.’’ Accordingly, there was an element of tradecraft. ‘‘I felt like a detective or a spy. Yes! Often I had uncomfortable moments. Nobody gave me a hard time, because I had a talent for not being noticed.’’

He was neither tall nor short, did not appear to maintain regular relations with razors, scissors or blankets and dressed in a way that brought to mind the bottom of a suitcase — ‘‘I didn’t change clothes too much.’’ The Ford fit the man. ‘‘I loved that car. It was like any car, inconspicuous,’’ he says. ‘‘I called it Luce — the only connection I ever had with Mr. Henry Luce.’’

Robert Frank in 1958. Credit: John Cohen/L. Parker Stephenson Photographs, via Getty Images

Robert Frank in 1958. Credit: John Cohen/L. Parker Stephenson Photographs, via Getty Images

Years later, the photographer and curator Philip Brookman learned just how committed Frank was to making pictures. The two men were visiting Frank’s troubled son Pablo on Thanksgiving at a psychiatric hospital. Many families were there. At one point a patient sang a very clear and beautiful song she called ‘‘Sad Movie.’’ Brookman, moved, crept his hand toward his camera, but he worried that taking a photo would be inappropriate. As the moment passed, he heard a familiar, gruff voice: ‘‘You should have taken it.’’

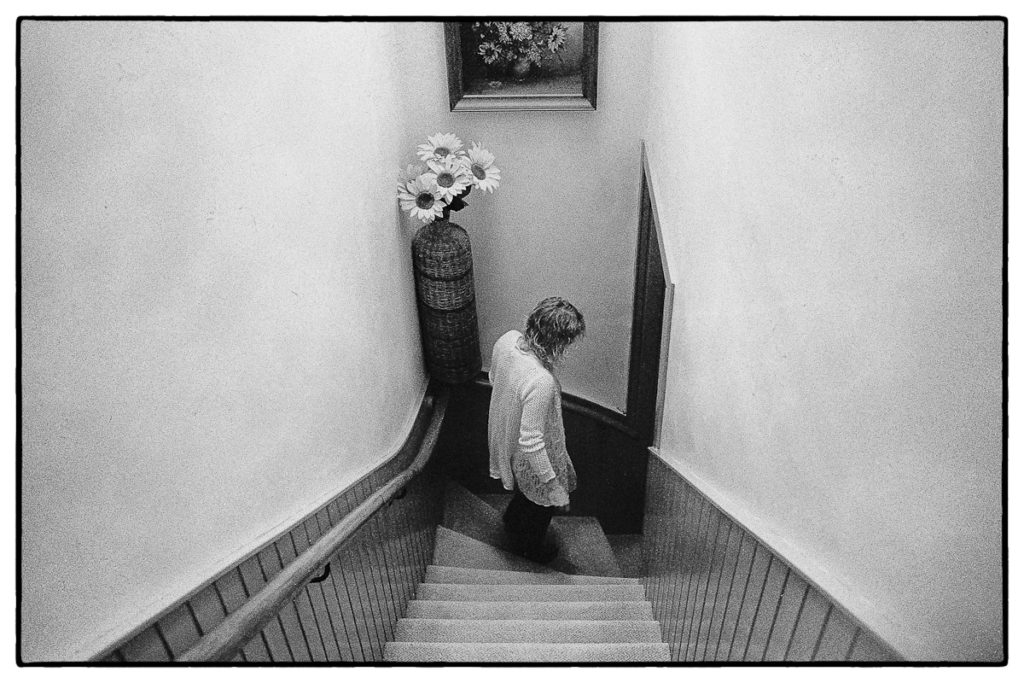

When Frank raised his camera and shot, the process was blurry quick, meaning he could capture what he saw as he perceived it. People, Frank says, ‘‘don’t like to be caught in private moments. I think private moments make the interesting picture.’’ It says something about Frank that his favorite ‘‘Americans’’ photograph shows the only people who caught him in the act. A black couple resting on the grass in a San Francisco park looks toward the lens in outrage. Beyond them are white city buildings. What is conveyed is how it feels to be violated wherever you go.

Frank says he was most drawn to blacks: the bare-chested boy in the back of a convertible; the woman relaxing beside a field in sunny Carolina cotton country; the dignified men outside the funeral of a South Carolina undertaker, who uncannily bring to mind the day President Obama eulogized Clementa Pinckney. At first, the South was to him ‘‘very exotic — a life I knew nothing about.’’ Then, in November 1955, Frank was traversing the Arkansas side of the Mississippi River, ‘‘just whistling my song and driving on,’’ as he says, when a patrol car pulled him over outside McGehee. The policemen’s report noted that Frank needed a bath and that ‘‘subject talked with a foreign accent.’’ Also suspicious were the contents of the car: cameras, foreign liquor. Frank was on his way to photograph oil refineries in Louisiana. ‘‘Are you a Commie?’’ he was asked.

Ten weeks earlier, Emmett Till was murdered a hundred miles away. ‘‘In Arkansas,’’ Frank recalls, ‘‘the cops pulled me in. They locked me in a cell. I thought, Jesus Christ, nobody knows I’m here. They can do anything. They were primitive.’’ Across the room, Frank could see ‘‘a young black girl sitting there watching. Very wonderful face. You see in her eyes she’s thinking, What are they gonna do?’’ Because his camera had been confiscated, Frank considers the girl his missing ‘‘Americans’’ photograph. Around midnight a policeman told Frank he had 10 minutes to get across the river. ‘‘That trip I got to like black people so much more than white people.’’

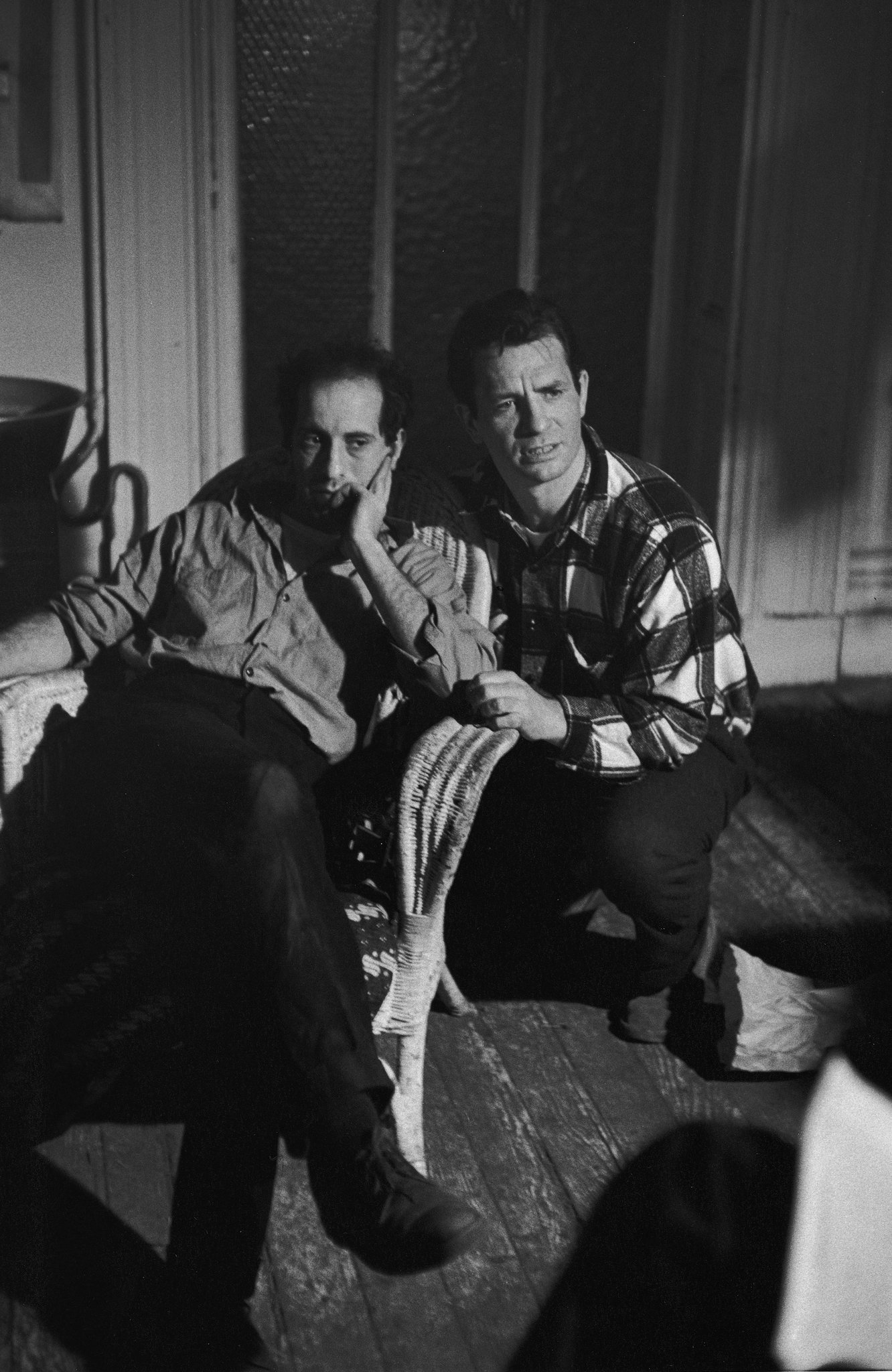

Frank, left, with Jack Kerouac on the set of the film ‘‘Pull My Daisy’’ in 1959. The film adapts a scene from Kerouac’s never-finished play, ‘‘The Beat Generation,’’ into a proto-‘‘Seinfeld’’ shaggy-dog story, indie cinema before the idea existed. Credit: John Cohen/L. Parker Stephenson Photographs via Getty Images

Frank, left, with Jack Kerouac on the set of the film ‘‘Pull My Daisy’’ in 1959. The film adapts a scene from Kerouac’s never-finished play, ‘‘The Beat Generation,’’ into a proto-‘‘Seinfeld’’ shaggy-dog story, indie cinema before the idea existed. Credit: John Cohen/L. Parker Stephenson Photographs via Getty Images

Coming to America after growing up listening to tyranny on the radio, Frank had been foremost a grateful émigré, and early pictures suggested it. Now, through a lens, the country darkened, and Frank became, the photographer Eugene Richards says, ‘‘a loaded gun.’’ Four days later, in New Orleans, Frank photographed the line of faces looking through the trolley windows. Once he saw that girl in McGehee, he says, he knew what to look for.

As he drove, Frank was in the grip-flow of his imagination, finding pictures everywhere, so many pictures that he now says of the period: ‘‘You don’t have it that good all the time. I was on the case.’’ Occasional hitchhikers advised Frank where to go next and spelled him behind the wheel while he slept in the back seat or quietly raised up and snapped their pictures, as he did on U.S. 91 outside Blackfoot, Idaho. Sometimes he gave people rides — workers, prostitutes — but Frank did not seek personal connections. ‘‘The people in ‘The Americans,’ I watched,” he said, adding, ‘‘I wanted to take the picture and walk away.’’

One ‘‘Americans’’ photograph came from a dimly lit New Mexico gutbucket: ‘‘It was a tough bar. You had to shoot from your hip.’’ In Elko, Nev., Frank photographed the play at a gaming table: ‘‘It’s very seldom you get a picture of people gambling. The management and the gamblers don’t want you to take pictures because they have wives. Or mothers! Or grandmothers! Or daughters!’’ At political gatherings, where credentials were required for admission, Frank was not above filching some from a stranger’s jacket.

You could operate that way if you were on your own, but Frank was married, and those years were hard on the family. In photographs from the 1950s, the children are inevitably bright-eyed, Mary is distantly aglow and Frank grim. From the road Frank wrote to Mary, ‘‘Your letters are often sad.’’ When they all met up in Texas and drove west for a few weeks, Frank found it ‘‘stressful. You go out, you’re gone. You come back, you’re tired. You’ve hunted for pictures. You want peace.’’ His family became the subject of his book’s wistful last photograph. Taken from in front of the car through the windshield, weary, overwhelmed faces and half the Ford are visible. ‘‘It’s personal, it’s melancholy, it’s sentimentality — all the things you try to stay away from. Also, I’m the person who’s not there. This is what it takes, the picture says.

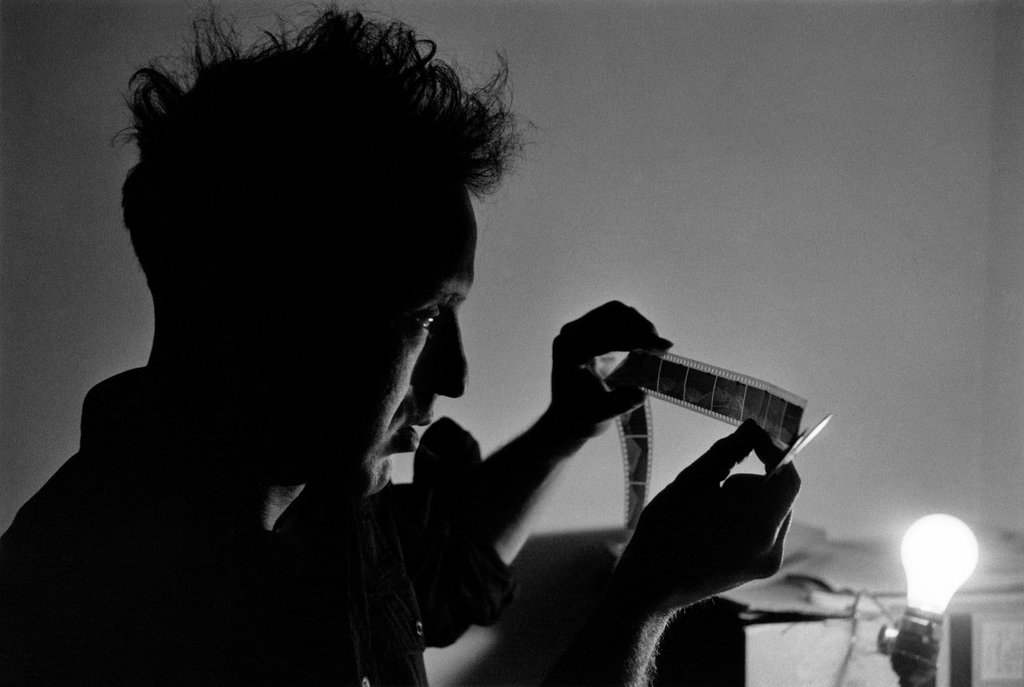

: Frank in 1956, looking at negatives in California while photographing “The Americans.” Credit: Wayne Miller/Magnum Photos

Frank in 1956, looking at negatives in California while photographing “The Americans.” Credit: Wayne Miller/Magnum Photos

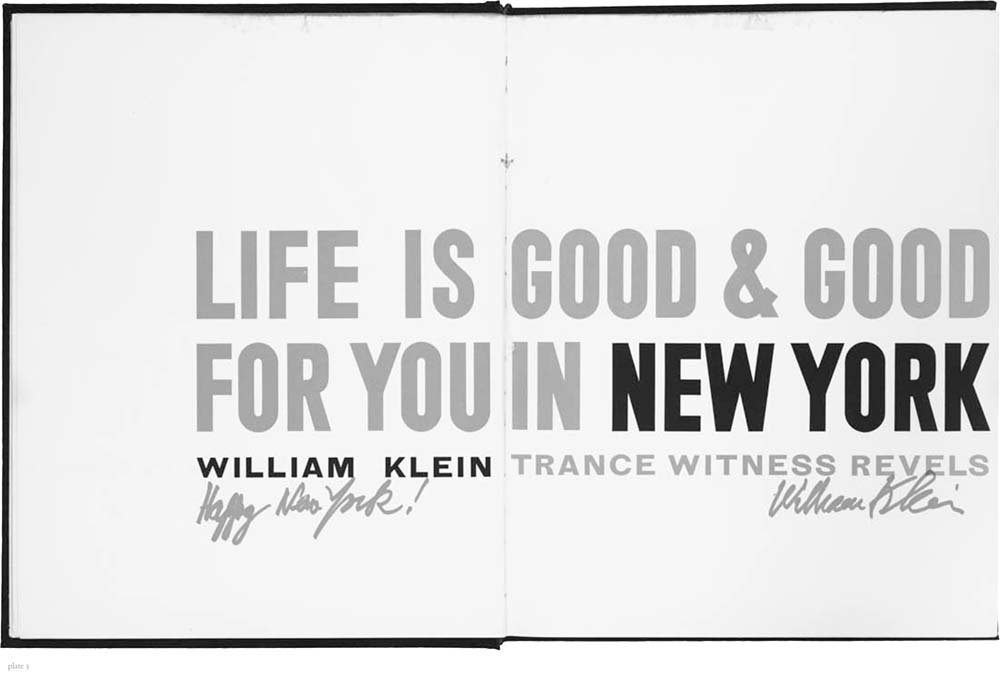

Frank took more than 27,000 photographs. Returning to New York, he sequenced the best 83 into what he thought of as a film on paper. Walker Evans wrote him an introduction to help place it. But who would publish images of groping teenagers, drifters, cross-dressers, poor blacks, a harassed mother? At first, only Robert Delpire in Paris would. Frank’s inability to find an American publisher frustrated him. He came to feel he needed a more like-minded advocate. So, Frank says, ‘‘I turned to Kerouac.’’

It was early September 1957 when Frank heard about ‘‘On the Road,’’ a novel that had just been praised in The New York Times as ‘‘the most important utterance yet made by the generation.’’ Frank ‘‘liked the speed of it, taking you back and forth across the country, his descriptions of the landscape in the morning, the little towns, which he describes with such exquisite beauty — the love for America.’’

He found Kerouac ‘‘at a New York party where poets and Beatniks were. Some painters. Everything happened downtown.’’ When Frank showed the writer his pictures, Frank says he was empathetic. ‘‘Kerouac personified what I hoped I’d find here in America. He was interested in outsiders. He wasn’t interested in walking the middle of the road.’’ Seizing the moment, Frank asked if Kerouac would introduce ‘‘The Americans.’’ ‘‘Sure,’’ Kerouac said. ‘‘I’ll write something.’’

One reason many other artists believe, as Nan Goldin says, that Frank ‘‘has never taken a false step’’ is that Frank always puts art above sentiment. ‘‘I try to get out of sentiment’s way when it comes near me. A few steps backward and to the left and don’t look back.’’ Frank says there was no hesitation about jilting Evans for Kerouac, but informing his mentor that he was forsaking him for Kerouac ‘‘was a difficult moment.’’ He says Evans’s essay was ‘‘too flowery and made no sense,’’ adding, ‘‘The friendship survived, but that was it. Never mentioned again.’’ Their relationship became ‘‘colder and more distant.’’

Frank admired Kerouac’s propulsive methods: ‘‘He lay on the floor all evening long. He’d write 20 pages about it the next morning.’’ Introducing ‘‘The Americans,’’ Kerouac told a reader nothing about Frank’s biography. Instead, he supplied an ecstasy of overture: ‘‘With one hand he sucked a sad poem of America onto film, taking rank among the tragic poets of the world.’’

Yet ‘‘The Americans’’ was initially unappreciated in the United States. The editors of Popular Photography derided Frank’s ‘‘warped,’’ ‘‘wart-covered’’ ‘‘images of hate.’’ That the photographs were blurry, asymmetrical, shot at oblique angles and deliberately informal attracted more screeds. The problem was, as the critic Janet Malcolm would later explain, ‘‘no one had ever made pictures like that before.’’

At first, it was other American artists who were enthralled. Out in Los Angeles, Ed Ruscha was sitting in an art-student cafe when a classmate brought in a brand-new copy of the book. Suddenly ‘‘there weren’t enough chairs for everyone; we were craning our necks, looking at it page by page. It’s like — You know where you were when John F. Kennedy was shot? I know where I was when I saw ‘The Americans.’ ’’ For Ruscha, in Frank’s hands the camera became a new kind of machine. ‘‘I was aware of Walker Evans’s work. But I felt like those were still lives. Robert’s work was life in motion.’’

Frank was not yet well known, but he and Mary were a glamorous couple at the crossroads of the New York arts scene. He personally was a camera, a tough, sensual receptor with an enticing remove that made others draw near. The people Frank admired were judgmental, unpredictable artists who satisfied his need for heightened experience. The jazz musician Ornette Coleman ‘‘didn’t like many things — a very hard critic,’’ while the filmmaker and musicologist Harry Smith lived to insult people, lit fires, yelled ‘‘Heil Hitler’’ in Jewish restaurants and yet was ‘‘the only genius I ever met. He was open to how people could reveal something for other people,’’ Frank says. ‘‘He lived uptown like a hermit, all alone with all his windows closed.

U.S. 90, En Route to Del Rio, Texas,’’ 1955. The final photo in ‘‘The Americans,’’ showing Frank’s wife Mary and his son, Pablo. Credit: Robert Frank via Pace/MacGill Gallery

U.S. 90, En Route to Del Rio, Texas,’’ 1955. The final photo in ‘‘The Americans,’’ showing Frank’s wife Mary and his son, Pablo. Credit: Robert Frank via Pace/MacGill Gallery

Among photographers, Frank considered Diane Arbus ‘‘a special woman! I went to her house. She was eating something. She said, ‘Do you want some?’ I said, ‘Sure.’ I took a bite. Almost impossible to eat. She said, ‘Yeah, I put too much salt in.’ She wanted to see my reaction. Why not? I liked her work. You could say, This is Diane Arbus.’’

Frank was closest to Ginsberg, Kerouac and their circle, and says he was inspired by Ginsberg’s relationship with the poet Peter Orlovsky: ‘‘Of course they were lovers, but he learned a lot about freedom from Orlovsky. They could live on the edge of society, the edge of American behavior. They made me want to be freer.’’ Frank would sit clothed in a room full of naked, stoned men as Ginsberg read from poems like ‘‘Kaddish.’’ ‘‘It’s wonderful to fall in with a group like that. You watch them live, and it’s so different from what you’d seen. Their art, their sexual lives, what truth they believed and preached and wrote. Ginsberg was a real prophet. He saw a different, more accepting America.’’

Frank once chauffeured Kerouac and his mother from Florida to Long Island; the author of ‘‘On The Road’’ didn’t drive. ‘‘It’s a better way to find out about the world if you don’t. He was true talent. He had a sad end. He couldn’t handle his fame. It drove him into a corner, made him drink, want to forget.’’ Frank found closer personal understanding with James Agee than he did with Evans, Agee’s collaborator on ‘‘Let Us Now Praise Famous Men,’’ and yet, Agee, too, was ‘‘always sweating and drinking, always a bottle close by. He was one of the saddest people I met, one of the suffering men.’’

When he wasn’t interested in someone, Frank could be pitiless. ‘‘I’m friendlier now. I had no patience.’’ He roiled with brutal standards: ‘‘In Provincetown, a guy showed me his pictures and asked me what I thought. I tore them up. Now I hate myself for that. Then I had to.’’

One day the painter Mark Rothko invited Frank to his studio for a talk. It was a dark space with only a row of windows on the ceiling because, Frank says, Rothko ‘‘liked the light to come in different colors. He had a daughter he worried about. He asked for advice on young people. I said I couldn’t help him.’’

Being an artist, husband and father continued to be arduous for Frank. During the ’60s, he seemed tired, angry and beaten-down to friends like the filmmaker Jonas Mekas, who recalls Mary once stopping him on the street to ask if she could borrow a dollar for groceries. The marriage struggled. But at the same time, Frank’s achievement was slowly becoming understood, a momentum that continues. The best photographers today, like Paul Graham, consider it still revelatory that someone could shape the endless onrush of American experience into a full portrait of the country. Frank’s book, Graham says, ‘‘expresses a yearning in us all to find meaning and a pattern, a form to life.’’

Among the many qualities that enabled Frank to achieve something so ambitious was his profound ambivalence. He was always that way personally, and it was how he could locate the full spectrum of any given feeling in the inscrutable faces of strangers. Critics like W.S. Di Piero believe his genius for expressing emotional complication came from an artistic innocence, the ability to look at the world as a child does — without the intrusions of experience. When June Leaf, Frank’s wife of 40 years, discussed with me this way of her husband’s seeing, she described being shown by his aunt a picture of Frank as little boy. ‘‘I looked at it, and I thought to myself, That’s exactly the same expression he has now: ‘What is going on here?’ That’s the secret of his perception of the world. And that’s ‘The Americans.’ That marvelous perception comes into the room. It’s ‘What is going on here?’ None of us know until he takes a photograph. Other than the photograph, he doesn’t know what is going on.’’

Over the years, ‘‘The Americans’’ would follow the trajectory of experimental American classics like ‘‘Moby-Dick’’ and ‘‘Citizen Kane’’ — works that grew slowly in stature until it was as if they had always been there. To Bruce Springsteen, who keeps copies of ‘‘The Americans’’ around his home for songwriting motivation, ‘‘the photographs are still shocking. It created an entire American identity, that single book. To me, it’s Dylan’s ‘Highway 61,’ the visual equivalent of that record. It’s an 83-picture book that has 27,000 pictures in it. That’s why ‘Highway 61’ is powerful. It’s nine songs with 12,000 songs in them. We’re all in the business of catching things. Sometimes we catch something. He just caught all of it.’’

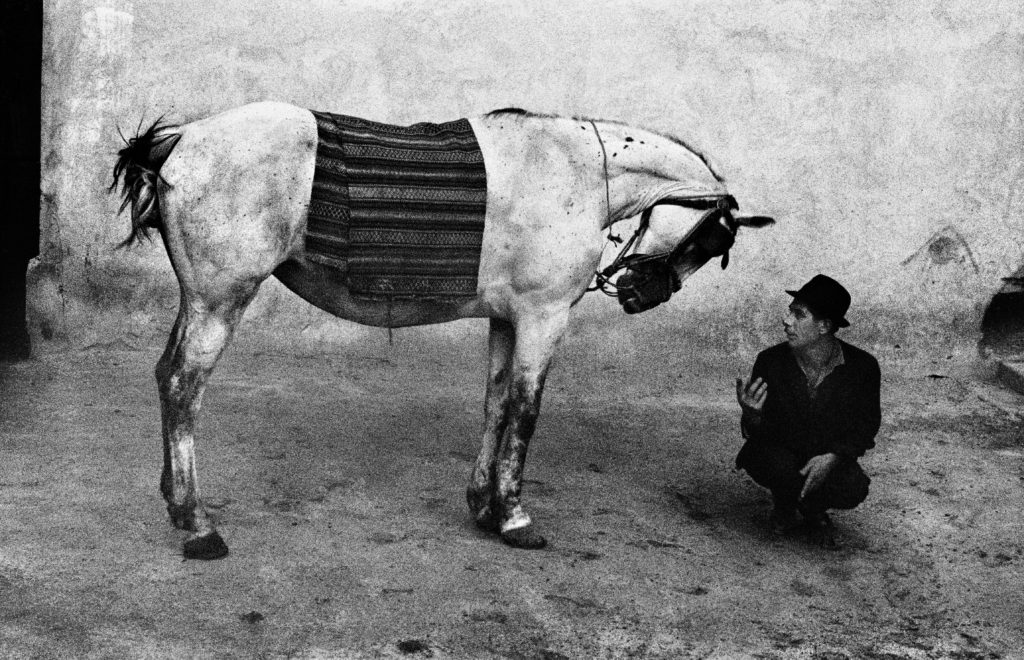

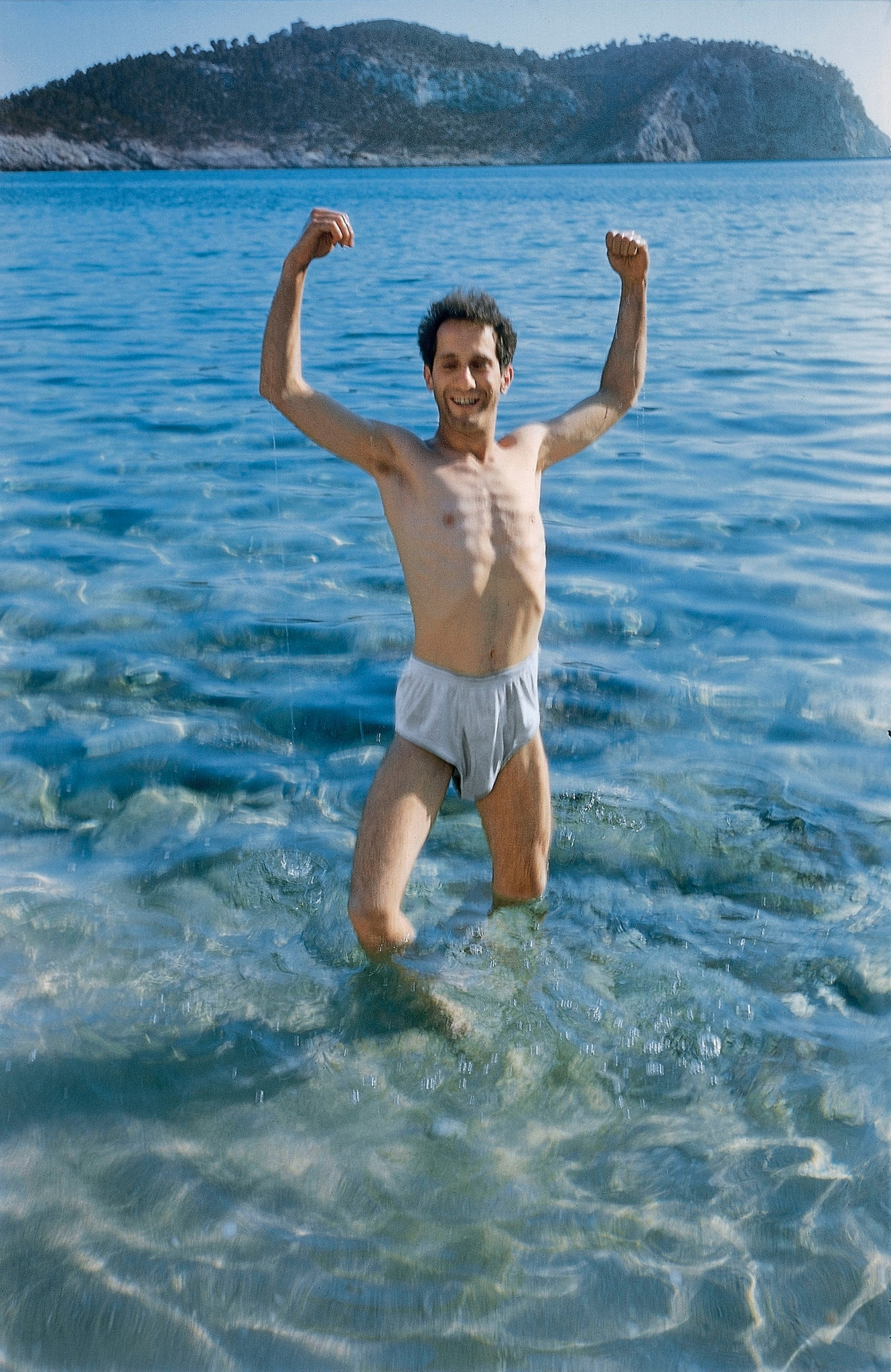

Frank in Spain in 1952. Credit: Elliot Erwitt/Magnum Photos

Frank in Spain in 1952. Credit: Elliot Erwitt/Magnum Photos

As ‘‘The Americans’’ thrived, Frank’s success weighed on him. In the early 1970s, his friend the photographer Edward Grazda received a piece of mail from Frank written on a scrap of ledger paper. The postmark was the remote mining village in Nova Scotia where Frank and his new companion, Leaf, had escaped the admirers clamoring outside his New York door. ‘‘Ed, I’m famous,’’ it read. ‘‘Now what?’’

Rare is the great figure — Marcel Duchamp, Jim Brown — who departs at the top of his game. That the man who made ‘‘The Americans’’ would leave photography was such a shocking decision that people in the arts still speculate about it. ‘‘He was painfully compassionate,’’ Peter Schjeldahl says. ‘‘Maybe he didn’t want the pain anymore.’’

Frank put it this way in 1969: ‘‘Once respectability and success become a part of it, then it was time to look for a new mistress.’’ He says now that the issue was creative fulfillment: ‘‘I didn’t want to repeat myself. It’s too easy. It’s a struggle, such a struggle to make something good, to satisfy yourself. That was relatively easy for me in photography. It’s immediate recompense. You’ve achieved what you set out to achieve.’’ The composer David Amram, a friend of Frank’s, says, ‘‘The last thing he wanted to be was what Miles Davis called a human jukebox — always be what made him popular.’’

In 1959, even as Barney Rosset, the American publisher of literary renegades like Henry Miller and D.H. Lawrence, released ‘‘The Americans,’’ Frank decided to ‘‘put my Leica in the cupboard’’ and began filming a silent movie with his downtown neighbor, the painter Alfred Leslie. ‘‘Pull My Daisy’’ adapts a scene from Kerouac’s never-finished play, ‘‘The Beat Generation,’’ into a proto-‘‘Seinfeld’’ shaggy-dog story. A railway brakeman and his artist wife host a church bishop for dinner, which is disrupted by a visit from a group of fizzed-up hipster impresarios who settle in to riff the night away.

Leslie’s loft was used as a set; their friends were the actors: Ginsberg, painters like Larry Rivers and Alice Neel and a cameo for the adorable Pablo Frank. Amram, who composed the music, recalls the shoots as ‘‘an insane party; everybody being juvenile and nuts. Leslie was a hostage negotiator — ‘Allen, if you’d please put your pants back on!’ ’’ Frank remembers Kerouac filling up on applejack and carrying on until he fell asleep. Later he ad-libbed the narration in three increasingly inebriated takes.

‘‘Pull My Daisy’’ was indie cinema before indie existed, the pure underground. There was scarcely any budget; the paychecks are still in the mail; only college students and avant-garde cineastes knew the film existed. But it endures as a cultural document — here were the Beats — and because nobody had ever seen anything like it. ‘‘If that came out of ‘The Americans,’ that’s a giant step,’’ Ed Ruscha says. ‘‘It’s almost totally different. I felt like it was guys on a hijinx. Films were usually professional enterprises done in Hollywood. This was choppy and crude and gutsy.’’ When Frank invited friends to a screening, he says, ‘‘they were happy somebody looked at the world in a different way.’’ Viewers still feel similarly, which pleases Frank, ‘‘especially because people didn’t really like my later films.’’

Across the next 40 years, Frank would release 31 mostly short, genre-eluding, quasi-documentary movies that met with even less success than ‘‘Pull My Daisy.’’ He says that working outside the studio system, operating ‘‘completely against the rules of how you made a film,’’ was challenging. And yet he filmed work that was, Jonas Mekas says, ‘‘very important. Same as Andy Warhol, he comes with his own world, his own sensibility, his own style.’’ The projects attracted a range of actors (Christopher Walken, Joseph Chaikin, Joe Strummer) and co-writers (Sam Shepard, Rudy Wurlitzer). Frank’s subjects were recondite: a book signing for a writer who never turns up; a day in the life of a country letter carrier. Another, about indigenous American music, strayed and became a film about Frank. As Laura Israel, Frank’s longtime film editor, says, ‘‘He’s all about the detour.’’

Frank also made a series of jagged, strangely absorbing personal films about friends and family that were so unlike anything preceding them that collectively they constituted a small documentary wave of their own. Three were about Pablo, a fragile, tortured adult whose life was increasingly derailed by schizophrenia. Another film, ‘‘Me and My Brother,’’ began as an adaptation of Ginsberg’s poem ‘‘Kaddish’’ and then, following the familiar digressive pattern, became an account of Peter Orlovsky’s relationship with his schizophrenic brother, Julius. Frank explains that he was always drawn to extremes: ‘‘There can be good extremes, but I had more connection with the other half.’’ And Julius, Frank felt, ‘‘was on the edge of something. I felt he would calm down and tell what it was like to be in this place.’’ Frank considered his filmmaking career ‘‘a failure,’’ because ‘‘often I don’t want to reveal. But because it wasn’t going well it kept me going.’’ Defeat perversely encouraged Frank; he liked what he couldn’t do. Except that he could.

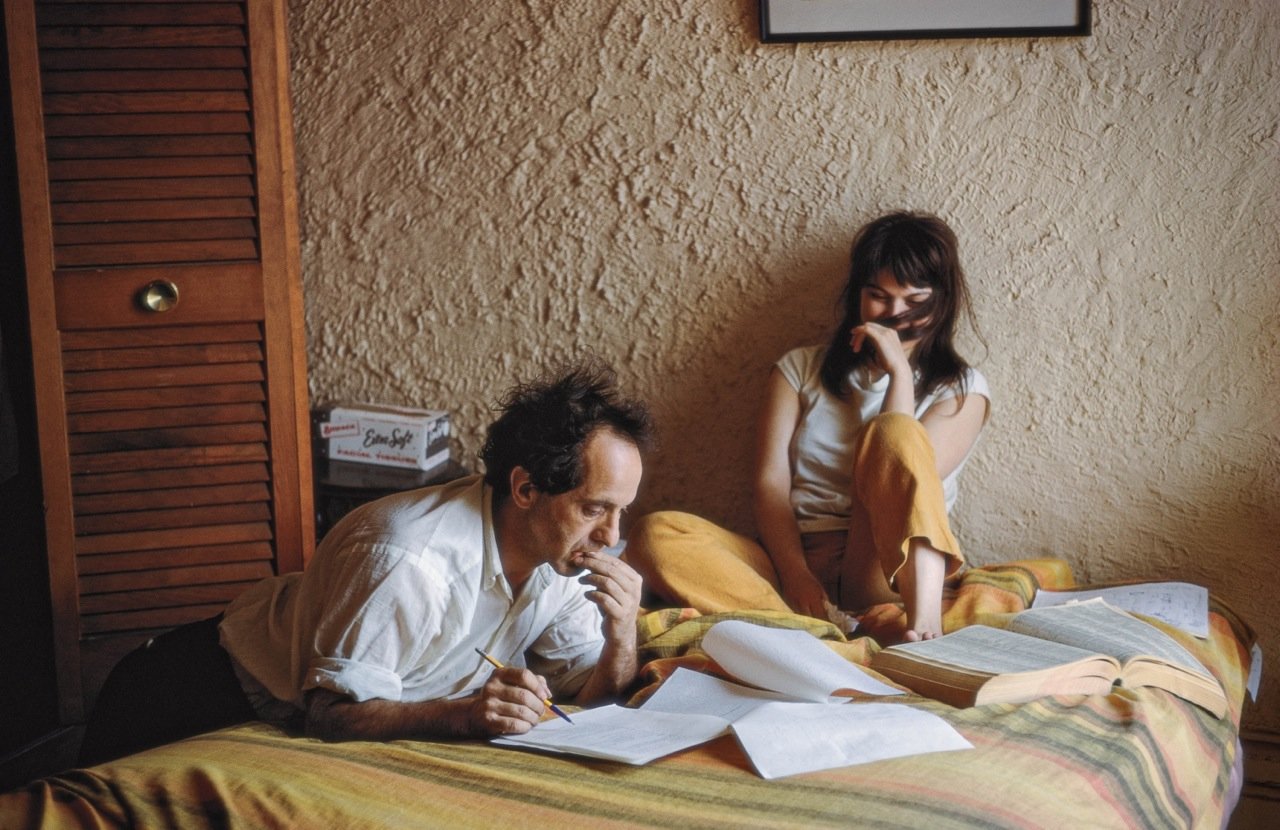

Frank with the actress Beth Porter on the set of “Me and my Brother,” in May 1967. Credit: Tod Papageorge

Frank with the actress Beth Porter on the set of “Me and my Brother,” in May 1967. Credit: Tod Papageorge

Frank’s most celebrated turn as a filmmaker came in 1972 when the Rolling Stones, in Los Angeles completing their album ‘‘Exile on Main Street,’’ invited him to photograph them for the cover. The musician who most influenced Frank’s work was Bob Dylan, who so frequently reinvented himself: ‘‘Dylan has the talents to move on.’’ But Keith Richards, Mick Jagger and the rest of the Stones were the world’s most celebrated outsiders, unregenerate avatars for collecting transgressive impulses into hits. At a fleabag Los Angeles inn, Frank recalls, they were instantly themselves. ‘‘Jagger said, ‘Let’s rent a room.’ I sat them down in chairs and made them use hotel furniture. That’s their life. Hotel rooms. Hotel rooms and polish.’’

The band was soon to go on tour, and they invited Frank and his Super-8 along. In the resulting film, ‘‘ Cocksucker Blues,’’ the band and its entourage are becalmed travelers ordering room service, gargling, masturbating, getting it on with drugs and groupies, moving through places they have no connection to, looking for ways to overcome lethargy and longueur. Frank now says of the experience: ‘‘I didn’t care about the music. I cared about them. It was great to watch them — the excitement. But my job was after the show. What I was photographing was a kind of boredom. It’s so difficult being famous. It’s a horrendous life. Everyone wants to get something from you.’’

Frank showed Jagger a rough cut. ‘‘He looked at it and then he said, ‘Richards came out better than me.’ Probably was right.’’ Richards agrees, of course: ‘‘One of Mick’s hangups is himself. Robert made the better man win! It’s a very true documentation of what went down.’’

The Stones’ lawyers worried that the explicitness would create problems and forbade screening it unless Frank was in attendance. As a result, the all-but-unavailable ‘‘Blues’’ is a celluloid apparition. The novelist Don DeLillo watched a cheap bootleg reproduction. He’d admired Frank’s photographs for the way they ‘‘imply a story or a sociology,’’ but the film, DeLillo thought, was different. ‘‘There’s nothing behind it. There’s something pure.’’ In DeLillo’s ‘‘Underworld,’’ as characters view the film, DeLillo describes at length its crepuscular, edge-of-time feeling.

Frank in Mabou, Nova Scotia, in 1970, during a visit by Danny Seymour, a collaborator and friend. Frank and Seymour were photographing each other. Credit: From Raul Van Kirk

Frank in Mabou, Nova Scotia, in 1970, during a visit by Danny Seymour, a collaborator and friend. Frank and Seymour were photographing each other. Credit: From Raul Van Kirk

Since the 1970s, Frank’s subversive approach has made him a godfather to young filmmakers. ‘‘The strength of his films is in what he says is problematic,’’ Jim Jarmusch says. ‘‘The beauty is they don’t satisfy certain narrative conventions.’’ Out in Texas in 1995, Richard Linklater was just beginning his film career when he staged a Frank retrospective at a theater in Austin. ‘‘If Robert Frank weren’t so acclaimed as one of the most influential photographers of all time, he’d have a much larger profile as an American indie filmmaking icon,’’ Linklater says. ‘‘It seems our culture struggles with the idea that someone could be that groundbreaking in more than one area. If it were just the films, I think he’d be credited as a founding father of the personal film.’’ He adds: ‘‘Beyond that, there’s this tremendous range of a restless, searching artist pushing the boundaries of the documentary, experimental and more traditional narrative forms.’’

During his 1969 short documentary, ‘‘Conversations in Vermont,’’ Frank portrays Pablo and Andrea confronting their youth spent growing up with a mother and father who put their art first. ‘‘You always said you wanted normal parents,’’ Frank challenges his children. That same year, Frank and Mary separated and Frank immediately began life with Mary’s friend June Leaf.

Overwhelmed in New York, craving ‘‘peace,’’ Frank asked Leaf to go to Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, to find them a home. It was winter. She bought a pair of thick boots and flew north: ‘‘He knew I’d do anything for him,’’ she says now.

They moved to Mabou, where the March wind was so strong you had to walk backward. They knew nobody, and the house they’d purchased overlooking the sea was, in the local expression, ‘‘after falling down.’’ As a young woman, Leaf was given a prestigious Paris studio to work in, and now in Mabou, she found she had sufficient inner creative stamina to make art in what her husband calls ‘‘a sad landscape’’ where ‘‘the sheep ate all the trees.’’

Rebuilding the house became their creative collaboration. ‘‘You learned a completely different rhythm of life,’’ Frank says. ‘‘It has to do with keeping warm and getting your food. That occupies most of your time. It’s severe. With time we found two friends.’’

Soon came devastation. Frank’s daughter, Andrea, aspired to become a teacher and a midwife. She was radiant, with flashing, dark eyes that infatuated Frank’s young photographer friends. Leaf likens her to Frank himself: ‘‘marvelous, like him. She intimidated people because she made everybody want her to love them. She was so similar to him — stern, critical, sexy, tough. Very tough. She was interested in life!’’ In 1974, Andrea died in a plane crash. She was 20.

Frank went immediately to the United States, leaving Leaf alone and wretched on a Nova Scotia island in winter, frightened that Frank would no longer love her because she could not fully share his grief.

Within a year of Andrea’s death, Pablo had cancer as well as schizophrenia. ‘‘Pablo,’’ Leaf says, ‘‘was a bird, a butterfly. The drugs he later took and the death of his sister pushed him over the edge into illness. That changed Robert incredibly, slowly, agonizingly. He became a sweet father to Pablo, where before he’d been explosive. Very critical, dictatorial, authoritarian, like many European fathers. Pablo was so ethereal, funny, charming, sweet. The illness made Robert a better father. He had to be.

For many years after leaving New York, Frank remained relentlessly productive; he made films and resumed taking photographs, personal images of a very different style from street photography. In 1972, a Japanese first-time publisher named Kazuhiko Motomura collaborated with Frank on ‘‘The Lines of My Hand.’’ An expanded American edition was published in 1989, and became a book crucial to American photographers. Jim Goldberg describes it as ‘‘a road map for the rest of us.’’ Many of the most powerful pictures are of Pablo, his face ravaged by illness. Photographs are distressed, dripping with tears of paint, rived with scratched-out messages. Of his son, Frank writes: ‘‘What a hard life we have together. I can’t take it.’’

In and out of institutions, Pablo committed suicide in 1994. ‘‘Robert was always attracted to mad people like Julius Orlovsky,’’ Leaf says, ‘‘because he had nothing of that in him. So it’s fate, isn’t it, Pablo.’’ Eventually, Frank gave in to grief. ‘‘It takes concentration for me to work and the wish to succeed,’’ Frank says. ‘‘I didn’t have it anymore.’’ With such loss, he said, ‘‘you have to cope every day, and it doesn’t go away. You try hard to find some peace and acceptance.’’

Frank dislikes talking about any of it: ‘‘It’s not good to look back too much. It’s often sad. Better to look forward.’’ I felt I should ask him about Leaf’s descriptions of his children. He didn’t disagree with anything she’d said. Then he sighed: ‘‘I could’ve helped him. He would’ve needed another family. A real mother, a real father to take care of him. I think about that too often, because it’s too late.’’

Frank and Leaf now live most of the year in a building off the Bowery that has open hearths and rough surfaces and feels like a vertical farmhouse, a Manhattan version of Mabou. In a neighborhood now awash in tony boîtes and boutiques, Frank and Leaf are remnants of vanished bohemian New York. In Frank’s musty basement studio, amid a jumble of contact sheets, Camus novels, toy crocodiles and checkerboards, ‘‘EAT’’ is scrawled on the wall in yellow. ‘‘Patti Smith wrote that,’’ he says.

Frank with his son, Pablo, in 1994 at Frank’s home. This photo appeared in The New York Times Magazine’s 1994 profile of Frank. Pablo died in 1994. Credit: Eugene Richards

Frank with his son, Pablo, in 1994 at Frank’s home. This photo appeared in The New York Times Magazine’s 1994 profile of Frank. Pablo died in 1994. Credit: Eugene Richards

Visitors are always stopping by. Leaf receives them bright-eyed — ‘‘I’m a bouncy!’’ Frank watches warily, but with an eyebrow raised. ‘‘He’s always waiting for something extraordinary,’’ Leaf says. Frank and Leaf married in 1975, while passing through Reno, Nev., an echo to the eloping couple in ‘‘The Americans.’’ Over the years Leaf has developed what she calls ‘‘a bad habit of studying Robert.’’ Once she asked me, ‘‘Do you think Robert’s elusive?’’ Instead, Frank answered: ‘‘I used to be. I didn’t like to explain anything.’’

‘‘You still don’t,’’ she said, ‘‘and you don’t like things to be explained, and I’m a great explainer. It’s a miracle we lasted this long!’’ At 85, Leaf has a grave, mystical face that resembles Georgia O’Keeffe’s. She sees her husband clearly — ‘‘You have no idea how mean Robert can be’’ — and with delight. In Philip Brookman’s 1986 documentary on Frank, ‘‘Fire in the East,’’ Leaf says: ‘‘He goes through life in this wonderful secret way, in the water, under the water. And things just come to him. So he’s like a fish, a beautiful fish in the dark, lighting up the water.’’

Although Frank still retains a certain Swiss civility, he enjoys provocation in others. He refers to the French celebrity photographer Francois-Marie Banier, notorious for insinuating himself into the affections of wealthy older women, as ‘‘the bad-man friend of mine.’’ Onstage at Lincoln Center, when his chosen interviewer, Charlie LeDuff, asked about the state of Frank’s rectum, Frank was amused at the general mortification.

Some days Frank is a steel door; others he is impish, a trickster. Not long after he renounced his Leica, word circulated among other photographers that he was entering photo contests under assumed names and winning. Ask him how he is, and Frank may reply, ‘‘Fifty percent!’’ What does that mean? ‘‘If it goes below 50 percent, my red light goes on!’’ One day, he loves crowds. Another day, crowds are ‘‘impossible.’’ A third pass, and the dark eyes gleam, and there’s nothing like ‘‘a medium-size crowd.’’ His terse style of speaking sometimes produces epigrams: ‘‘It’s the misinformation that’s important.’’

January 29, 2013 photo of Frank at his New York home, with a note by the photographer Jim Goldberg: “I’ve known Robert Frank since 1979 and this is the first time that I photographed him.” Credit: Jim Goldberg/Magnum Photos

January 29, 2013 photo of Frank at his New York home, with a note by the photographer Jim Goldberg: “I’ve known Robert Frank since 1979 and this is the first time that I photographed him.” Credit: Jim Goldberg/Magnum Photos

‘‘Take that seriously,’’ warns Brookman, who has known Frank since the 1970s. ‘‘He loves misleading people.’’ When Frank is feeling affectionate, his puckish banter is seductive to younger artists — especially photographers. Many men have felt for a time like a second son to Frank, only to abruptly find that some sort of personal fission has occurred, the focus of Frank’s guarded eyes has moved on and they’ve been purged. His longtime gallerist Peter MacGill has grown accustomed to offering consolation: ‘‘Robert hurts the people he’s closest to.’’ One photographer, in an anticipatory gambit, stopped talking with Frank for more than two years. When I met MacGill, he warned me, ‘‘Everybody who knows him gets periodically fired.’’

‘‘It’s that you’re not a contestant anymore for something extraordinary,’’ Leaf says. ‘‘We all fall short. It’s the way a man desires a woman. This is the one! He’s always hoping somebody will change the view of the world.’’ The personal quality Frank perhaps values most is autonomy, and when others want too much from him, he gets prickly and feels exploited; it’s time to leave. ‘‘It was always important to him to remain independent of Switzerland, his family, Life magazine, Cartier-Bresson, Evans and go forward, keep pushing,’’ Brookman says.

There have been unbroken bonds. Sarah Greenough, senior curator of photographs at the National Gallery, says Frank and Motomura always ‘‘were devoted, even though Robert didn’t speak Japanese and Motomura didn’t speak English.’’ Another person on whom the door has never closed is Peter Kasovitz, the gregarious owner of K&M Camera in New York. Many in Frank’s community wonder why Kasovitz should be spared. Frank, whose father sold electronics, says Kasovitz is the consummate independent operator: ‘‘He doesn’t go by others’ rules. He just runs things in a way he believes.’’

For decades, Frank refused honors and exhibitions. He once skipped a private celebration for the Museum of Modern Art’s new photography curator because he wanted to test the set of tires he’d just acquired for his Subaru. But lately, he attends his openings; this summer he accepted an honorary degree from the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design.

Frank retains the spontaneous enthusiasm of a much younger man. In his tenth decade, he is still a free-form outsider seeking untried situations, fresh leaps — and nothing pleases him more than picking up on the scent of something exceptional. Last year, after receiving intriguing letters postmarked North Carolina from an itinerant laborer named Gustavo, Frank set off to find him. He discovered Gustavo in Winston-Salem painting a house, he says, but ‘‘I was disappointed in him. He was ordinary. He seemed not to be possessed by anything. He just drifts.’’

A more satisfactory result came after an unannounced knock on the door from a California family. The father, Leaf says, ‘‘was a junk collector looking for a masterpiece.’’ Recently he’d purchased three pictures. ‘‘One looked like it was from Woolworth’s, and he thought it was a Boucher. The second was the worst thing you ever saw. He thought it was a de Kooning. The third, somebody tells him it’s a Sanyu. He looks it up and sees Robert knows him.’’ So the family crossed the country by car to show Frank the painting possibly by Sanyu. ‘‘You don’t have to open your eyes to see it’s not a Sanyu painting,’’ Leaf says. ‘‘He doesn’t mind. He’s a speculator! He’s happy!’’ Eventually, Leaf and Frank had to go out. ‘‘What do you want to do?’’ Leaf asked their visitors.

‘‘Nothing,’’ came the answer. ‘‘We came to see you.’’ The family made their hosts tortillas from scratch and drove off for Louisiana to surprise an aunt.

Frank found all of this immensely satisfying. ‘‘I liked his directness. Completely direct. I could tell them about Sanyu. They had no interest in June or in my photographs.’’ And so Frank decided that the father should have his masterpiece after all. ‘‘I sent them two of my photographs. I wonder if they found out what people pay for a print like that.’’

Nicholas Dawidoff is the author of five books, most recently ‘‘Collision Low Crossers,’’ an investigation of the inner life of the New York Jets that was a finalist for the 2014 PEN/ESPN Award for Literary Sports Writing.