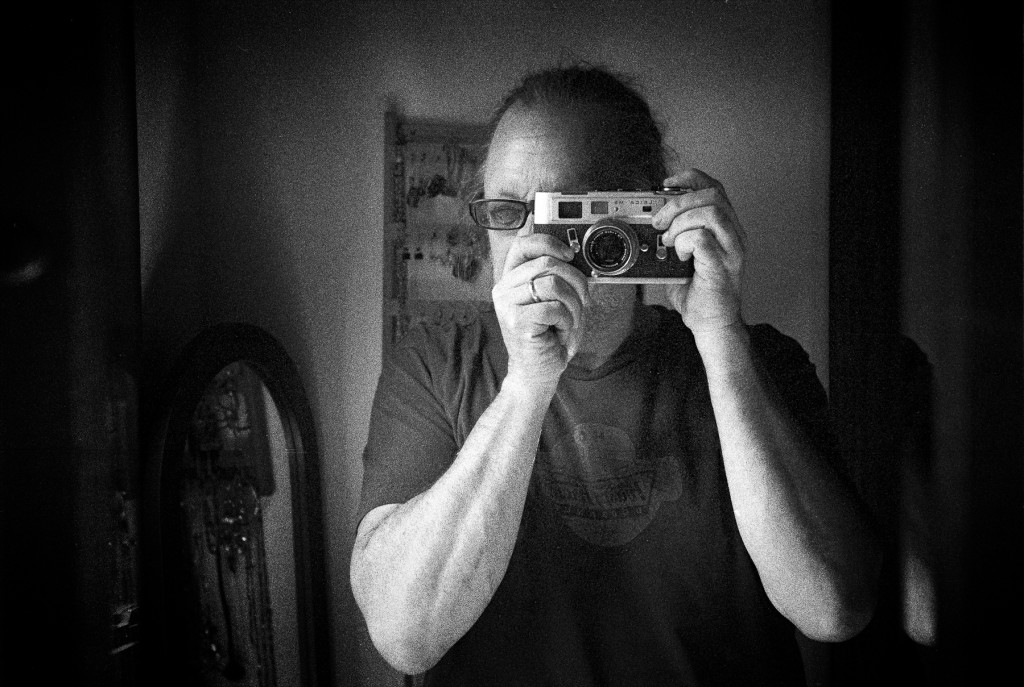

This is a reprint of A Guide on How to Shoot Street Photography on a Film Leica (or Rangefinder) written by Eric Kim and originally published September 2, 2014 on his blog Eric Kim Street photography Blog. [Editors Note: I like Eric Kim. I recommend his blog. It’s good that we have a new generation of photographers who’ve discovered film and are enthused about its possibilities. I also like that he “gets” the traditional appeal of Leica rangefinders i.e. not a a signifier of status, but as photographic tools.]

I know a lot of street photographers who have gotten into film recently, and have recently invested in film Leicas (specifically Leica m6’s). I wanted to write this guide to share everything I personally know about shooting on a film Leica based on my 3 years of experience. Disclaimer: I am not a Leica expert, nor do I claim to be. But I will to share some practical tips and insights about film Leicas and how to shoot them on the streets.

Which film Leica to get?

If you’re reading this article, either own a film Leica and shoot street photography, or might be interested in getting one.To get this out of the way, the best bang-for-the-buck film Leica is the Leica M6. It includes a meter, and is relatively modern. I recommend getting one via my good friend Bellamy Hunt from Japan Camera Hunter (or eBay with good sellers, reliable second hand stores, or on Craigslist after you see it in person). Also note: m2, m4 and m4-2 do NOT have 28mm framelines (thanks to Anon):

A quick rundown of all the film Leicas out there:

Leica M2:

I deal for 35mm lens, but doesn’t have a built in meter, and has a “cold shoe” (the hotshot doesn’t fire). Also loading film in it is a a pain in the ass. But you can get good deals on a film Leica M2. If you are good at metering with your eyes, this is a good bargain.

Leica M3

Apparently one of the best Leicas ever made– this is the Leica Henri Cartier-Bresson shot with most of his life. Has a beautiful viewfinder, and is ideal for a 50mm lens. Unfortunately, natively it can’t use a 35mm lens (unless you get attachments for it). Similarly to the m2, doesn’t have a hotshot and loading film in it is annoying. If you are a 50mm guy, it is a good body.

Leica M4

Great film body, the camera that Garry Winogrand used for most of his life. You can find great deals on these. Doesn’t have a built in meter.

Leica M5

A lot of people hate this camera because it looks ugly, but some great work is being made with it (Junku Nishimura uses one). It is bigger, chunkier, but some argue the ergonomics are better.But if you don’t care about aesthetics, I’d go for it (if you can find a good deal on it).

Leica M6

The best bang-for-the-buck film Leica to get. Has a built-in meter, fast rewinder, and is also the camera that Joel Meyerowitz and Bruce Gilden shot for a long time. Also as a note, there is a Leica M6 TTL which has a larger shutter speed dial (same as the Leica M9), and it supports the SF20 flash ttl mode. Also apparently a little bit more rugged than the M6 (as it is a bit newer). This was the first film Leica I owned, it was given to me as a present from my friend Todd Hatakeyama. I recently “paid it forward” by giving it to another talented photographer named Bill Reeves in Austin, as he needed the camera more than I did and needed a film body to create beautiful work.

Leica M7

The most electronic film Leica out there– it is still being made by Leica. It has aperture priority mode, and exposure compensation. Downside of the camera: you can only use two shutter speeds if the battery on the camera dies (all the other film Leicas are fully mechanical, and can shoot without a battery). Also, I have heard from other photographers that if isn’t as reliable as the other film Leicas (provably due to all the electronics). Ideal if you want aperture-priority, and don’t like manually changing your shutter speed.

Leica MP

The newest film Leica, still made by Leica– (mp stands for “mechanical perfection”, pretty cheesy but the most robust of all film Leicas). The Leica mp has the styling of the old M2–3, is made out of solid brass, and is the newest one (thus the most reliable one). This is currently the film Leica I use. I sold my M9, bought a used Leica MP (in mint condition from Japan Camera Hunter) and pocketed the change. The reason I chose the MP was partly aesthetic (I like how the black paint brasses over time) and mostly because it is the most reliable (I can’t have my camera fail on me while traveling).

The body doesn’t matter that much

To be honest, the film Leica body you get doesn’t matter that much. You can’t tell the difference of image quality of a $800 Leica M2 compared to a brand-new $5000 Leica MP. However you should ultimately choose your body based on your personal needs (if you like having a built-in meter, if you shoot with a flash, and what focal length you shoot with). Also note that all film Leicas (except the M3) support frame lines of 28, 35, 50, etc). Any lenses wider than 28, and you need an external finder.

Jorge Fidel Alvarez, Leica M6, 35mm Summicron, Ilford HP5, Wuhan, China 2014

Lens choices for a film Leica

For 99% of street photographers, I’d recommend getting a 35mm lens. 28mm is too wide for most people, and 50mm can be a bit cramped. The best bang-for-the-buck lens for a film Leica is the Voigtlander 35m f/2.5 – as you will probably be shooting at f/8 most of the time, and if is very cheap (less than $400) and very compact. If money is no option and you want the sharpest and most ergonomic lens, I’d recommend the Leica 35mm Summicron ASPH f/2 (great ergonomics, build quality, and incredibly sharp).

Some other great Leica lenses (if you don’t like 35mm) and can afford it:

Other good bang for the buck options are:

–50mm Zeiss f2 (or voigtlander equivalent)

–28mm Voigtlander f/2

However at the end of the day, your focal length is your personal decision.

My suggestion: try experimenting with different focal lengths and see which one you like the most. Then once you find your ideal focal length, just stick with it. Also disregard all these bokeh, sharpness tests online for lenses. I think it is better to have a light and compact lens, you honestly don’t need a lens faster than f/2.8 if you’re shooting street photography from f/8–16.

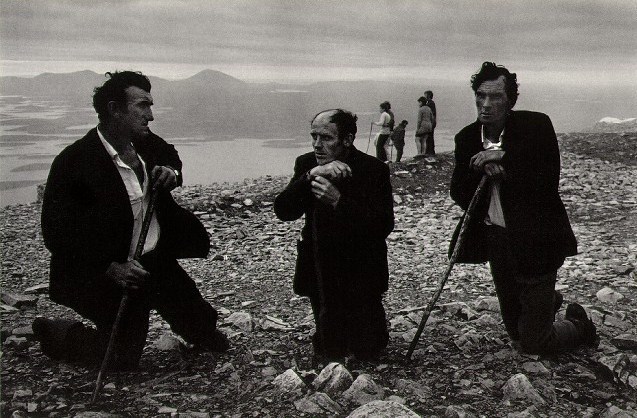

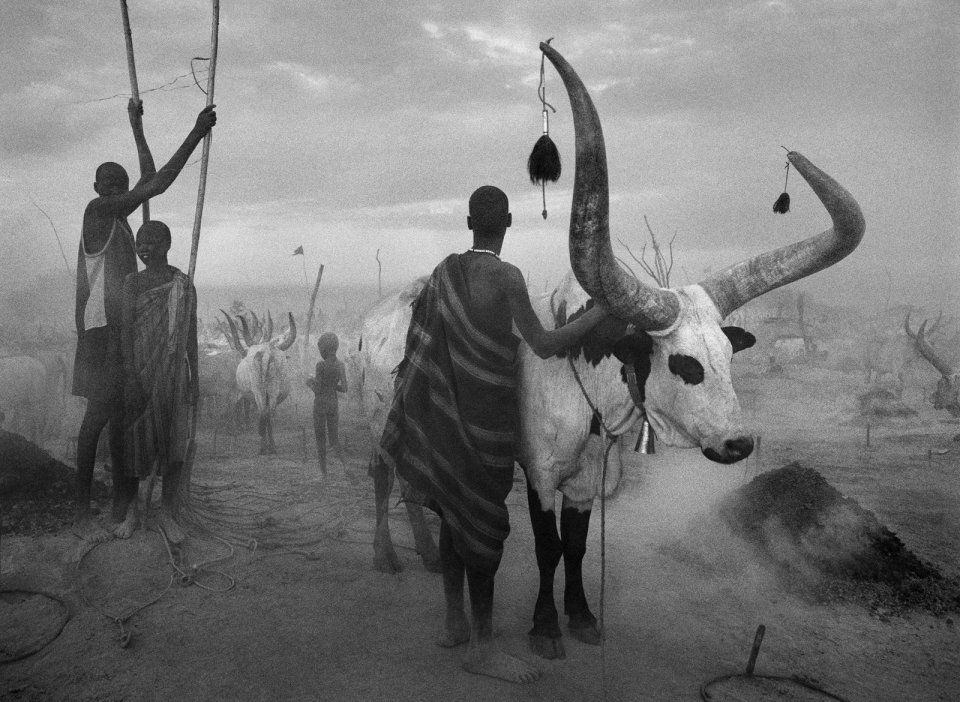

Zone focusing

Leica’s aren’t meant to be shot wide open in street photography. You can’t constantly nail f1.4 shots of people moving. Furthermore bokeh shots in street photography tend to be cliche, and you lose context of the background and environment. To be frank, very few great photos in history were shot wide open. Most were shot with a relatively deep depth of field (f/8–16) to get a context of the subject and the background. When you shoot with your film Leica, I recommend you keep your aperture at f/8 by default (remember the saying, f8 and be there). This gives you a deep depth-of-field (everything is in focus) and lets enough light into your lens (sometimes f/16 causes your shutter speed to be too slow). I generally keep my lens pre-focused to 1.2 meters (the focusing tab is smack dab center) when I’m out on the streets. 1.2 meters is roughly two-arm lengths away.

When I see a subject around 3–5 meters away, I just turn my focusing tab 45 degrees to the right. When the subject is very close to me, I turn my focusing tab 45 degrees to the left (.7–1 meter). Over time, you should learn how to judge your distances well. For example, start to learn how far away .7 meters (around one arm-length), 1.2 meters (2 arm lengths away), and 5 meters (the average distance of a street from the curb to the storefront). Over time, your finger will intuitively focus with the focusing tab based on how far your subject is away from the subject.

Some lenses unfortunately don’t have focusing tabs on them. In those cases, either glue on a focusing tab (you can find them on eBay), or know how much you have to turn your wrist to the left or right when focusing.

What you don’t want to do when shooting street photography is this: bring up your Leica to your eye, put your focusing patch on your subject, and fool around for 5–10 seconds trying to nail your focus.

What you should do is this: see how far your subject is, pre-focus to that distance (without looking through your viewfinder), bringing up your camera to your eye and quickly shooting.

Essentially a Leica in street photography should be used like a point and shoot camera.

Jorge Fidel Alvarez, Leica M6, 35mm Summicron, Ilford HP5, Wuhan, China 2014

The benefits of shooting with a film Leica

Personally I don’t think I’ll ever purchase another digital Leica. I once owned the Leica M9 (it was a solid camera)– but now it has lost so much value in a short period of time. This is my reasoning: all digital cameras are essentially computers. How long do you keep your computer for– probably not longer than 4–5 years. Which means you have to keep upgrading them. A digital Leica re-sale value is quite low. After a year or two of owning a digital Leica, you lose around $1000–2000 in value. And they will probably get updated every 2–3 years. So if you shoot digital and love it (and are rich), I’d say go for the digital Leicas. After all, there is no other better digital rangefinder in the market.

But for me, I like the idea of buying a film Leica and owning it for the rest of my life. A film rangefinder will never go out of style. In 50 years my grand children can still use the camera, and it will still be “functional”. But I doubt a digital camera will still be relevant in 59 years. Because once the lithium battery runs out of charge, it will be useless.

Also with a film Leica, I fall less victim to “GAS” (gear acquisition syndrome). I’m not in a rush to upgrade my cameras, because there is nothing more updated than a film Leica. There will never be a Leica mp version 2 with video. This allows me to make no excuses about my photography, as I have the best film rangefinder that money can buy.

To also be honest, Leica film rangefinders aren’t as expensive as they seem. You can get a great condition Leica M6 for around $1500–2000. That’s not cheap, but around the same price as a Fuji x-series camera, or a modern DSLR. You can get a great Voigtlander lens for around $400 (Voigtlander 35mm f/2.5 lens) which is probably 80%+ the performance of a $3000 Leica 35mm f2 Summicron ASPH lens. And in terms of “sharpness”, I can’t tell a difference between voigtlander, Leica, or zeiss lenses.

Nobody is going to care how sharp your photos are at the end of the day– they’re only going to care the emotional impact and composition of your images.

Alternative film rangefinders

Don’t get me wrong, there’s also tons of great affordable film rangefinders. You don’t need a Leica. The Yaschica electro 35mm is solid, as well as the Voigtlander Bessa And Zeiss Ikon cameras. For me, I prefer the film Leicas because they are more robust, have a more “classic” design, and have been around for a longer period of time. I also prefer the ergonomics. But each man to his own.

On shooting film

Film can get a bit pricy depending on where you live. But if you shoot black and white film and process it yourself, it is quite cheap. Also take into account that if you shoot digital, you upgrade constantly (every few years). With a film rangefinder or Leica, you will never really “need” to upgrade. When shooting film, you also shoot less. So I don’t think the whole “…but I can shoot 1000 photos a day on digital and save money in the long run.” Most street photographers I know rarely shoot more than 1 roll of film a day.

When I’m at home and not traveling, I probably only shoot 5–10 photos a day. When I’m traveling, I might shoot half a roll to a full roll depending on how exciting things are. I know some street photographers who only shoot 1–2 rolls a week. My favorite film for color is Kodak Portra 400, and Kodak Tri-X 400 for black and white. But experiment with different films and see what you like.

Some good alternatives:

- Ilford HP5 (black and white)

- Kodak Gold 400 (affordable color film with good saturation and gritty look)

Scanning your 35mm film

For me nowadays I shoot on Kodak Portra 400 color film, and I get it processed in the states at Costco. It only costs me $5 usd a roll, including develop and scan (3000px wide). The quality looks good to me (all the film photos on my flickr and website are from Costco). They use professional Fuji equipment (for developing and scanning)– and I’m pleased. You can also go to local convenience stores or drugstores if they offer it (for color film). Just test out a few test rolls in different areas, and see if you like the results. Sometimes labs will screw up your negatives (so always experiment different locations).

With black and white film, I hand process it myself (professing black and white is expensive in the states) and scan it myself with an Epson v750 (the Epson v700 orPlustek 8200i are better affordable options). I process just with a changing bag, and use hc–110 developer from Kodak which is quite good. I have heard my friends having great results with “rodinal” developer (for a nice gritty look). Ultimately the chemicals you use is personal preference.

For scanning, I just recommend using the default silverfast software. You can get a solid job with it.Flatbed scanners aren’t as high quality as dedicated 35mm scanners (like the plustek) but honestly– for the web, they are good enough. If you want museum quality scans, get it professionally drum-scanned.

Printing your photos in the darkroom

If you shoot black and white, I highly recommend making darkroom prints. The experience is absolutely incredible, and really gets your hands dirty.

I heard printing color is much more difficult (I’m going to learn how to do this soon), but the results are stunning. My friend Sean Lotman from Kyoto does all his prints himself in his color darkroom, and scans his prints onto flickr. I’ve seen his prints first-hand, and they absolutely blow me away.

So if you shoot film, I recommend both printing and scanning the negatives. Do whatever you enjoy and have fun doing.

Will shooting with a film rangefinder make you a better photographer?

For me, I think shooting with a film rangefinder hasn’t necessarily made me a better photographer– but it has made me a lot more patient, brutal when it comes to editing my photos, and has given me a lot less excuses about my gear. So in a sense, my photography has improved shooting with a film rangefinder.

Rangefinders aren’t for everybody. They suck for a lot of stuff, such as:

- Framing isn’t as accurate as SLR

- Parallax error is annoying (when you frame your subjects closer than 1.2 meters)

- They don’t have a close minimum focusing distance (most rangefinder lenses only focus up to .7 meters)

But all in all, I don’t mind the restrictions of shooting with a film rangefinder much. Sometimes I feel the constraints help me be more creative with my framing.

Here are some pros of shooting with a film rangefinder:

- You can see outside of the frame lines, which allows you to see more of the scene in the street. (But if you wear glasses, you’re limited at 35mm. You can’t see all of the 28mm frame lines if you wear glasses)

- You don’t get viewfinder blockage when shooting (your viewfinder isn’t through the lens like a DSLR, so you don’t get viewfinder black-out when shooting)

- Small and compact (easy to always carry around with you in your bag, or around your neck, or in your hand)

- Dials are easy to change for shutter speed, aperture, and focusing distances.

So for me, a film Leica rangefinder is currently my ideal tool for street photography. This isn’t for everybody– I know some guys who take far better photos than I do just on an iPhone.

There is no “best” camera for street photography. Just find the “best” a camera for street photography for your personal preferences.

I do encourage experimentation for different camera systems (DSLR, micro 4/3rds, Fuji x-series, iPhone, compact cameras, rangefinder). Ultimately the camera system you like for street photography will depend on your preferences. Some of us like to eat vanilla ice cream, and some of us like chocolate ice cream. There isn’t one “better” flavor.

Editor’s Note: lots of good advice here, although I disagree with the author’s advice that the M6 is the best Leica rangefinder for street photography. In my mind, they’ll all, with the exception of the M3, as good as the other, and if I were to choose, I’d pick up the cheapest M2 I could find. Every M2 I’ve ever had has been super smooth in operation. Yes, it doesn’t have a meter – but you don’t need a meter when street shooting, just like you don’t need autofocus. A good rule: “F8 and be there!” which in practice means F8 and a shutter speed aproximating your film’s ISO, and go out and shoot. Film has latitude, a little over expose, a little under exposed, no big deal. The point is, stop fiddling with you camera and get the shot.