In the early 2000s, the world of photography changed forever. Though digital cameras had been widespread since the mid-1990s, the technology did not produce sufficiently high-quality results for professional and serious amateur photographers.

Around 2003, however, this changed, and vast swathes of professionals made the jump from analogue to digital, decimating an entire industry in the process. “Companies went from processing in the region of 5,000 rolls of film per day to 20 percent of that in a six-month period; as you can imagine, there were many casualties”, said Professor Steve Macleod, Director of Metro Imaging, a professional photography lab.

For a decade after this crash, sales of camera film steadily dropped as digital camera technology continued to improve. However, all was not lost for the analogue world. According to Kodak Alaris, a spinoff of legendary film manufacturer Kodak, sales of Kodak Professional film grew more than five percent worldwide between 2013 and 2015. Of course, this figure is not even close to reaching the dizzy heights of yesteryear, when film was the only tool available to photographers, but that might not even matter. Indeed, it seems the future role of analogue photography is not to challenge the dominance of digital, but to rest alongside it in a particular niche.

Legends of the past

Perhaps the best-known film producer in the world, Kodak is still operating in the aforementioned form of Kodak Alaris. What’s more, the company is continuing to innovate, with new films such as Kodak Portra designed specifically to be scanned, reflecting the preference of many modern film users to have scans rather than prints as an end product.

Kodak’s one-time rival, Fujifilm, is also still producing camera film, but focuses primarily on its Instax line of instant camera paper. This reflects one of the many unexpected trends in analogue photography; sales of Instax cameras have risen steadily since 2013, and are expected to hit five million units this year. This pattern is firmly being fuelled by a young demographic – typically those born and raised in the digital age, for whom a printed photograph is something of a novelty.

UK-based Ilford Photo, another of the few major players to survive the crash, confirmed this trend last year, after a survey found that 30 percent of film users were under 35 years old, and 60 percent had only started using film in the last five years. Such is the enthusiasm among this small but dedicated group that newer companies have even managed to find success in analogue photography – Lomography, born from a bizarre collective of photographers obsessed with low-fi Russian cameras, has also seen film sales rise steadily throughout this decade, with products such as Purple XR (a film that warps the colour spectrum) squarely aimed at the youth demographic.

Creative control

The question that these findings inevitably raises is – why? Why shoot film, when digital cameras are so advanced? In a sense, this line of enquiry is born of a misunderstanding. For many, there is an impression that film is an expensive medium compared to digital, which is ‘free’ in a sense, once the initial equipment has been purchased. “This is a myth. The cost of shooting analogue is immediate and physical: you have to buy film, you have to pay to have it processed and scanned. With these criteria, digital appears less expensive and many wonder why anyone would choose to shoot film. However, people fail to build into their costing how long it takes to edit digital photos. If they were to cost out how long it takes to edit and prepare digital files for production, it would be equivalent or near to the cost of shooting analogue; they balance out in the end”, said Macleod.

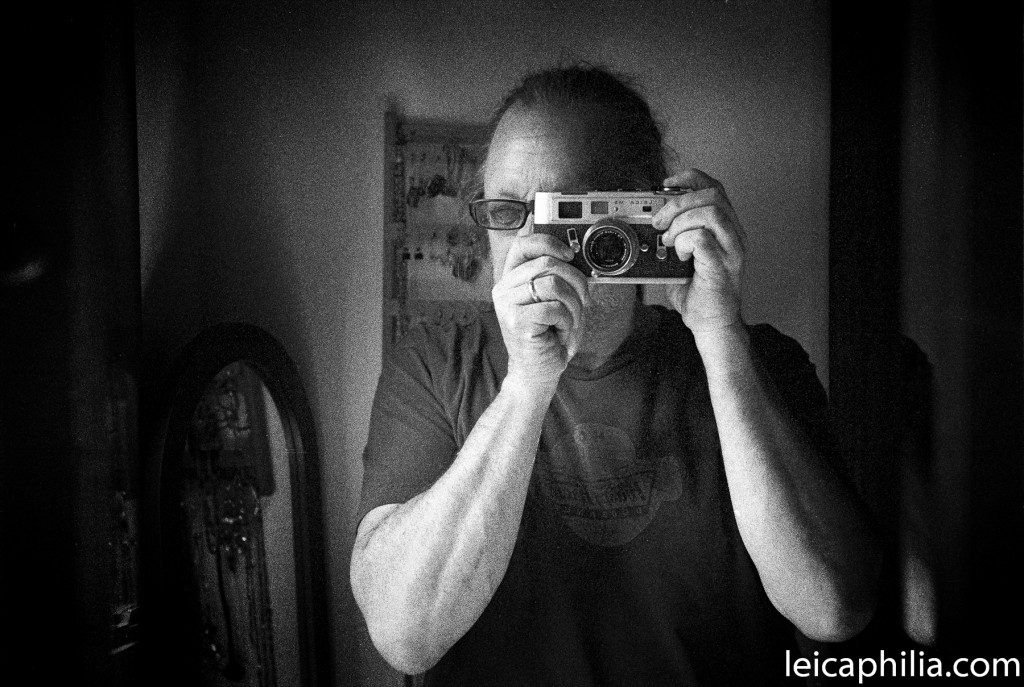

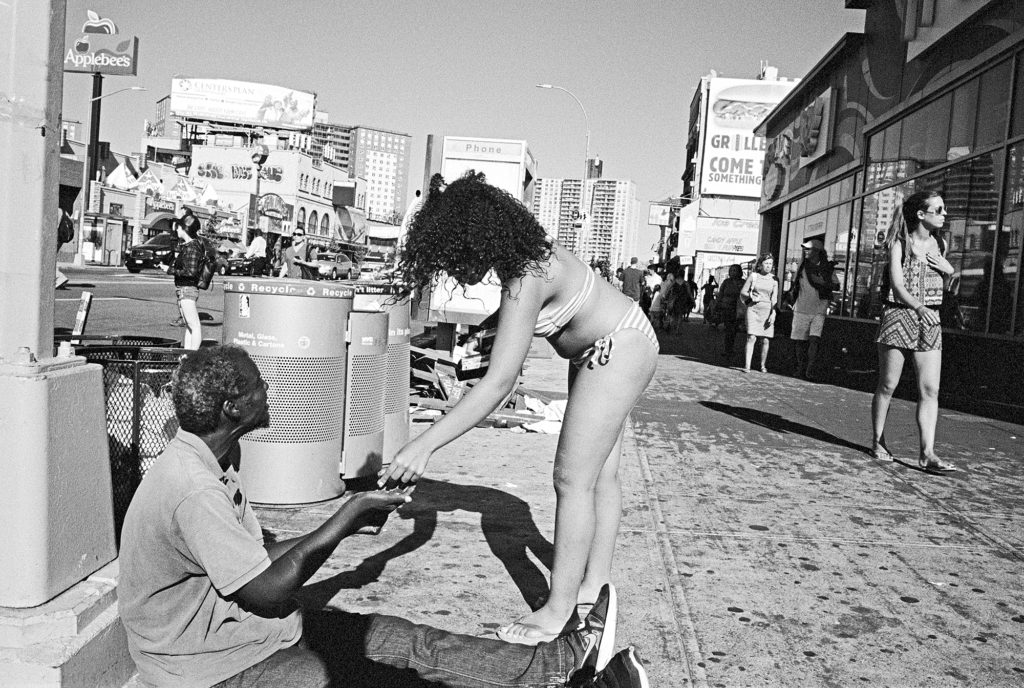

Similarly, there is often a lack of understanding of the experience of shooting film; the vast majority of digital camera users nowadays have never actually tried shooting with an analogue camera, just as most music listeners have never handled, played and fully listened to a vinyl record. There is a simplicity to the pared-down experience that can be of genuine creative benefit. “Necessity is the mother of invention; there is no point staring at the back of a film camera after taking a shot – that time and energy is already going into the next one. Not knowing immediately what has been captured is a creative advantage”, said Walter Rothwell, a professional photographer who regularly uses analogue cameras for his work.

Rothwell is not alone is this view, as more and more professional photographers are choosing film for similar reasons. This is particularly apparent in the world of fashion, as photographers seek to take back control of a creative process that is falling ever further into the hands of editors. “In the era of Avedon and Irving Penn, it was the photographers who were leading what the fashion should be. Today it is the fashion editor. It is the editor who is immersed in fashion, so it is the editor’s point of view that is valid…the photographer becomes just the tool to express that point of view”, said art director Fabien Baron, in an interview with Business of Fashion.

Je ne sais quoi

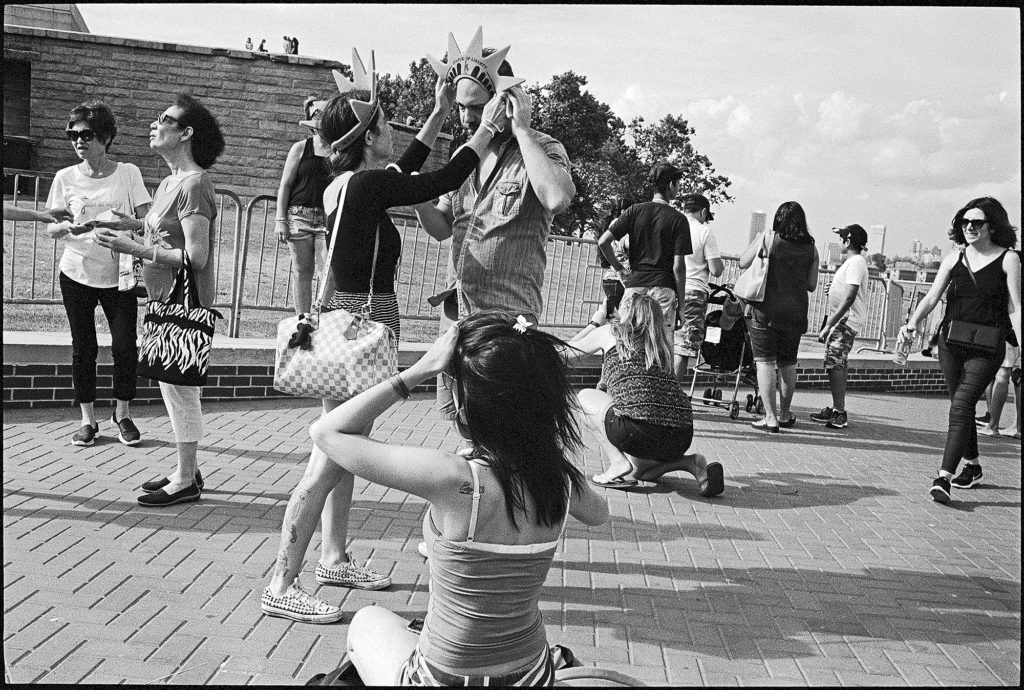

Of course, high-minded ideals about creative control and specific minutiae of costs are primarily professional issues. What inspires the everyday film photographer is something quite different, which is difficult to define, but easy to see.

“Film has a quality that is unique; a beauty and tonal warmth that digital cannot match. Like the vinyl versus MP3 debate, there is something inherently different about a physical process compared to a virtual one”, said Rothwell. While digital camera manufacturers have made photography a question of megapixels, a growing number of people understand that quality cannot be expressed in figures. Ken Rockwell, a prominent advocate of film photography, expressed this point well, writing: “Non-artists misguidedly waste their time comparing meaningless specs like resolution and bit depth, when they really should just stand back and look at the images.”

As well as the choice of medium, such considerations also influence the choice of camera for many photographers. Lomography’s Diana camera has extremely limited controls, uses a deliberately low-sharpness lens, and purposefully allows light to leak through the body and onto the film, and yet it is astonishingly popular, as the final images have a unique, dreamlike quality that simply cannot be recreated with any amount of computer processing.

For related reasons, the Hasselblad Xpan, a panoramic film camera, is one of Rothwell’s favourites for personal work. “The Xpan was a unique moment of madness from a large manufacturer; a comparatively small panoramic camera that shoots across two frames, producing very high quality negatives. Around 10 years ago, I noticed that I was ‘seeing’ panoramic photos, so I got the camera to answer a yen.” Rothwell’s panoramic street photography has earned him international acclaim, and while it would certainly be possible to use the panoramic mode on a digital camera or phone to replicate the effect, there is something about the lack of choice that lends his shots a unique feel. To stitch together a panorama from digital images with would not give the same results in terms of artistic impression, though the scene may be the same.

Self reliance

The most common process when shooting film is the same now as it was before the digital age. A roll of film is shot, rolled up, and taken or posted to a lab for development. The lab will then return prints and/or scans of the images, as well as the original negatives or slides for storage.

However, in this modern world of increased automation, there is a growing trend for manual processes. This has caused a minor boom in home developing, with many amateur photographers processing their own film and even attempting to make prints. Such has been the level of interest in recent years that, in 2014, Ilford launched Localdarkroom.com, a website designed to help photographers find a darkroom that they can work in, as most people lack the appropriate space or resources to do more than basic processing at home.

It is tempting to put this down to a desire to reduce costs, film photography being perceived as an expensive pursuit, but the reality is very different. “If you are developing and printing to save money, you’re barking up the wrong tree. There is no getting around it, film and paper are expensive, then there are the chemicals, negative and print storage costs, enlarging and processing equipment, the list goes on”, said Rothwell. People are keen to do things with their hands, not for reasons of quality or cost, but for the sake of it, and perhaps to satisfy a deeper instinct to produce physical work.

This desire for the physical extends to storage too. True, photographic prints have not seen their popularity rise in parallel with the rebirth of film, but having an exposed negative as a permanent record of a photo is something that speaks to people, especially as our understanding of the limitations of digital data storage increases. “I read an interesting quote recently: ‘nothing digital is truly archival, as it does not survive by accident’. We are taking unprecedented numbers of photos nowadays, but the vast majority are destined to remain as computer code, languishing on hard drives”, said Rothwell.

For the ages

Herein lies the problem – digital files do not last on their own. File types come and go – even the ubiquitous JPEG format may not be readable by standard hardware in 20 or 30 years – so constant, active conversion is required to ensure the survival of an archive. Properly stored negatives, however, can last almost indefinitely, with no particular action required. They are tangible records that can be passed down through generations.

In 2007, Chicago-based amateur historian John Maloof purchased a box of negatives from the 1960s for $400. They turned out to be the work of the now-revered documentary photographer Vivien Maier. Maloof now owns some 150,000 of Maier’s negatives, many of which have been successfully scanned, and he has been largely responsible for her posthumous fame. Could this have happened with a hard drive of JPEGs? The technology isn’t old enough to say for sure, but there’s cause for doubt.

Ultimately, this is not to say that everyone should immediately discard their digital cameras and switch to film, but rather that film still has a very real and serious place in the world of photography. As a specific tool in the photographer’s arsenal, alongside digital, film photography can continue to survive and thrive, offering something of an antidote to the mentality of snapping each and every passing moment. As Macleod noted: “The way people shoot has changed. Film has become a more considered approach; something people invest time in creating.”

The rebirth, however, is still just that – manufacturers need to continue to respond to the market and innovate as much as they can in order to make it a safe, reliably profitable industry once more. Whether that happens remains to be seen, but for now, film is most definitely alive and well.