By Christopher Moss. Mr. Moss is a retired family physician who has been taking photographs for 45 years, still with a strong preference for film

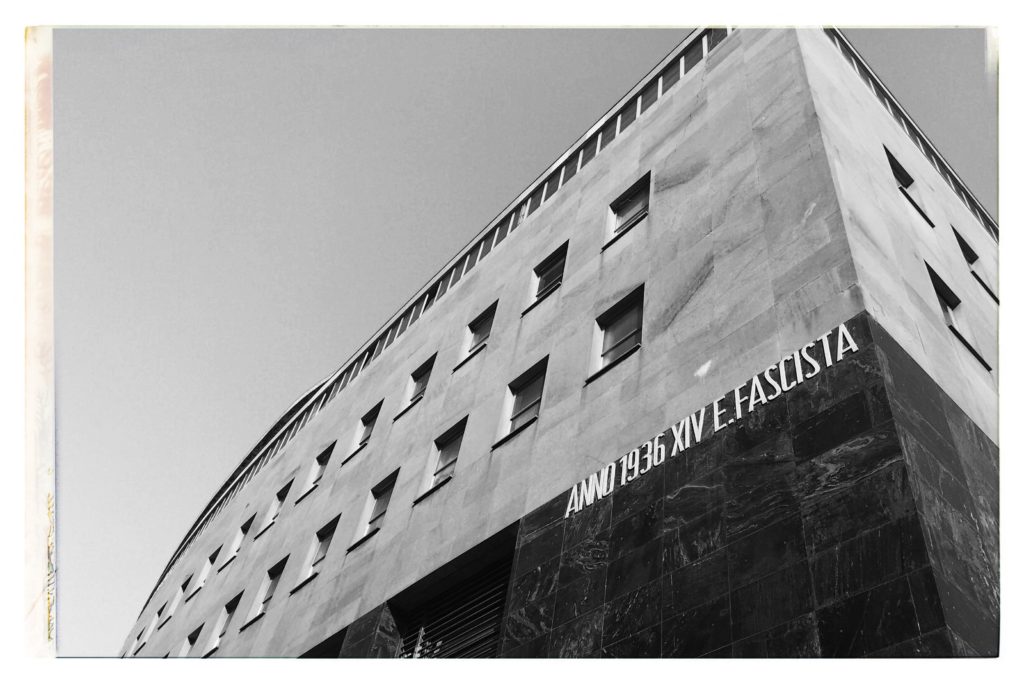

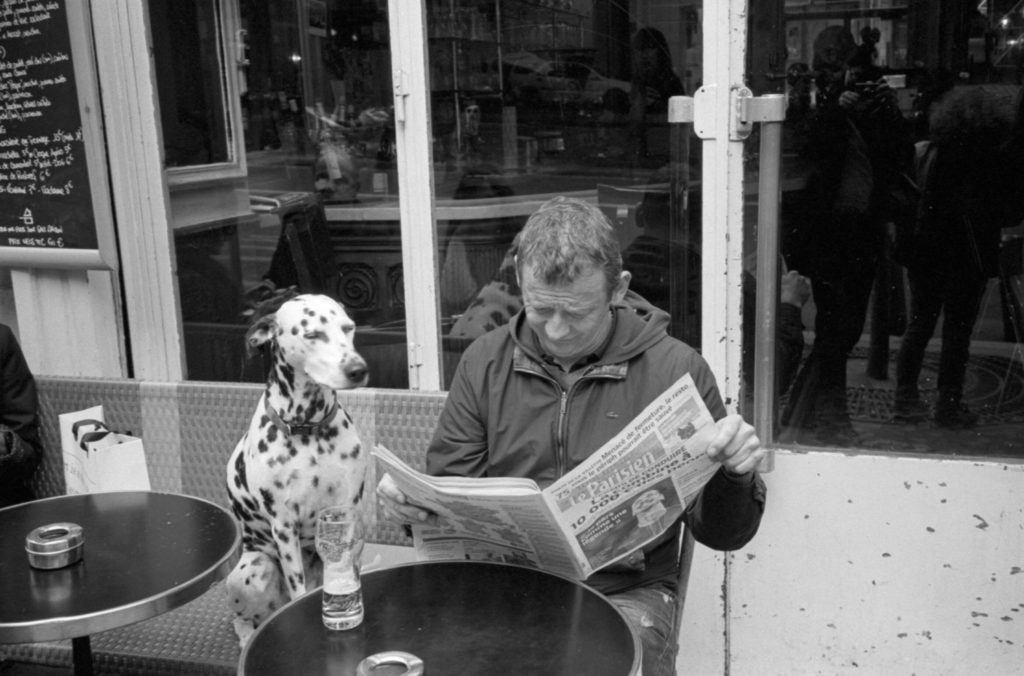

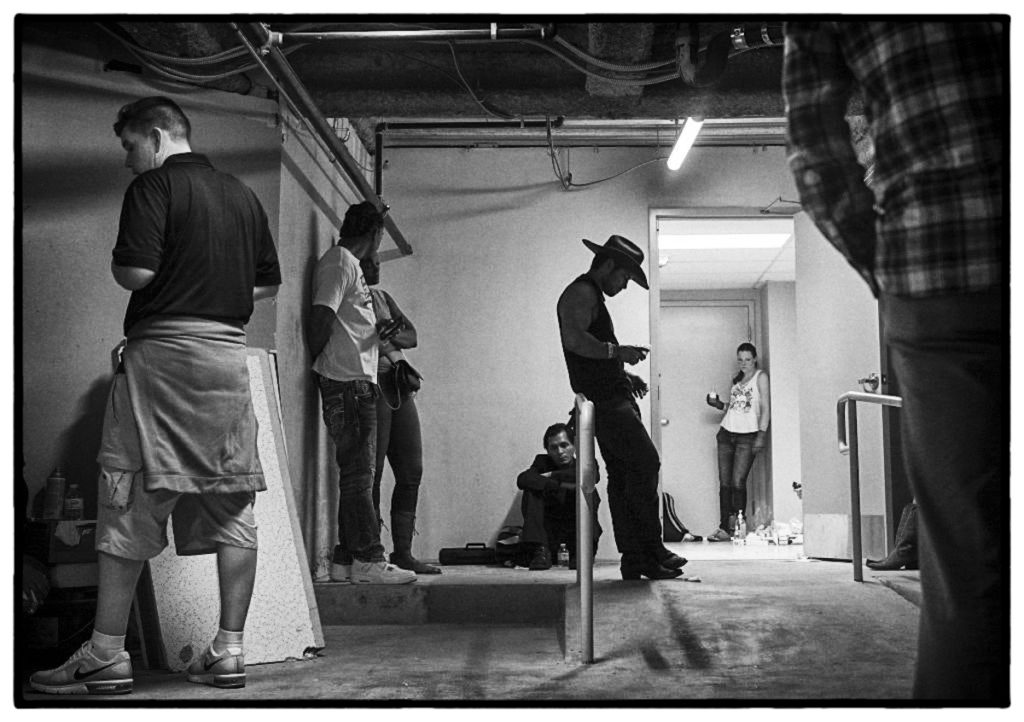

I was thinking recently, as all photographers probably do, about the way I make photographs. I’d had the experience of taking a few rolls of film and finding one or two pictures that worked out particularly well, and had enjoyed the experience of discovering a nugget of what seemed like gold amongst the dross. This was the one that started me going:

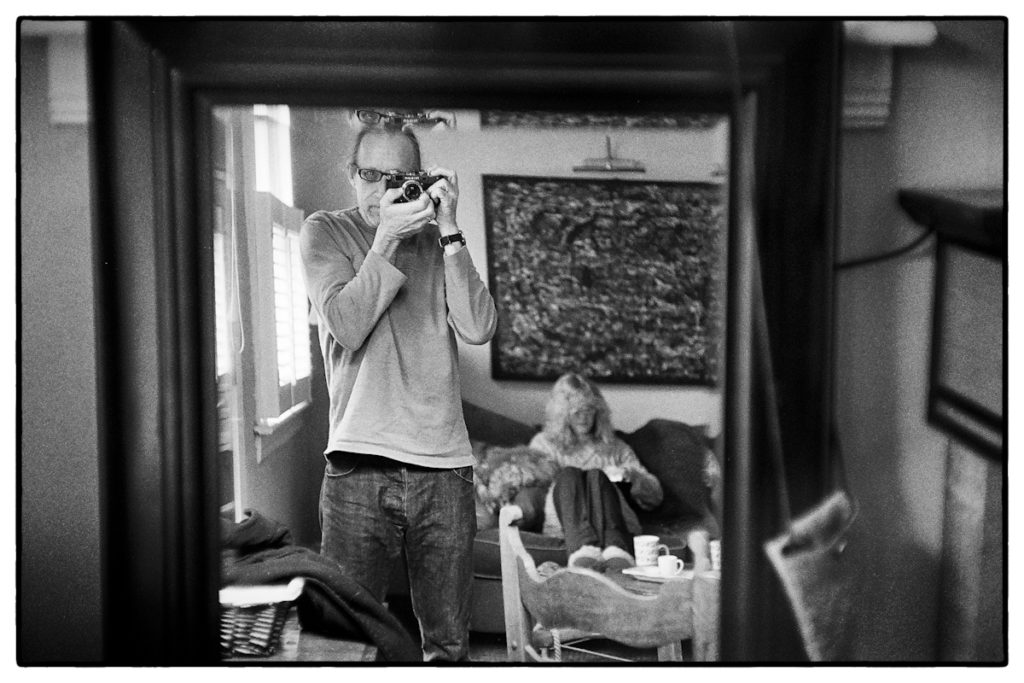

I’ll admit that this kind of found photograph is how I make the pictures I feel the most pride about. Perhaps I’m gradually learning to better predict what will work out to be pleasing, but I don’t have the temperament or the skill to plan a photograph in advance, arrange my subjects, and then take the image I had envisioned. Having thought about it for a few days, I started on a line of thought that led to some ideas, currently only dimly perceived, but again with a nugget of truth.

Photo-realistic Painting versus Photography

Somewhere in the early seventies, my father, once an amateur photographer and by then obsessed with painting, had taken me with him on a day trip to London to visit several art galleries. I think he was looking for inspiration, and we both came away with one painting in particular as memorable. Below is Annigoni’s portrait of Queen Elizabeth: This was my first exposure to a photo-realistic painter, and we spent some time with our noses as close as we could, marvelling at the invisible brush strokes. My father had principally made the trip to look at Impressionists, and he was of the view that a clever painter wouldn’t try to record exactly; he would hint at things and let the spectator’s brain fill in the details far more accurately than a brush could do. But for all his skill, Annigoni, and photo-realism in painting receives little respect, and the first assumption I’m going to make is that this is because he doesn’t show us the world changed slightly through his painting, he simply records it like some kind of human Xerox machine.

This was my first exposure to a photo-realistic painter, and we spent some time with our noses as close as we could, marvelling at the invisible brush strokes. My father had principally made the trip to look at Impressionists, and he was of the view that a clever painter wouldn’t try to record exactly; he would hint at things and let the spectator’s brain fill in the details far more accurately than a brush could do. But for all his skill, Annigoni, and photo-realism in painting receives little respect, and the first assumption I’m going to make is that this is because he doesn’t show us the world changed slightly through his painting, he simply records it like some kind of human Xerox machine.

Years after this visit, I came across Anthony Burgess’s definition of art as the use of a medium, so arranged by the artist as to re-present the world to an audience in such a way that it teaches them something new about it. Well, Annigoni didn’t show us something new, only what was there already, and which we think we already can see. There might be another factor at work, though this is pure speculation: if you have ever seen the drawings of savants who have that particular gift you will have been amazed at the accuracy of their draughtsmanship, and perhaps you will know that unlike the way we might draw by first making an outline and then refining it, savants tend to start in one corner and fill their canvas with complete and finished detail, gradually working across until they reach the other side.

Truly, brains be different. It may be that gifted photorealistic painters are also working in some way alien to the rest of us, and that neuronal atypicality which we often characterise as cold, aloof, and mechanical discourages that introduction of that human element that makes an artistic representation have the quality that Burgess referred to—we learn nothing new in seeing it as there is no sense of seeing through another’s eyes. And yet, photographers are given that respect for their work. The camera, which is said to never lie, is being used to present us sights that do more than simply record a small slice of reality at a particular moment. How is this the case? Why is photography worthy of more artistic respect than photo-realistic painting? I’m going to suggest that it is because the camera does lie, in that it does record the world in a different fashion than our own eyesight, and there are simple optical (and far more complex neurological) reasons for this. We’re going to have to delve into the physiology of human vision.

Eyeballs and Image Processing

This isn’t going to be hard, as I’m simply going to remind you of the things you ought to have been taught in school biology classes. Eyeballs are often compared to cameras, and the analogy holds true from the cornea backwards, but not once we get to the retina and the complex image processing that takes place in the optic cortex. Both are light-tight containers with a hole in the front. The cornea and lens function together to focus light rays on the light-sensitive film, sensor or retina. The iris functions just as the aperture of a camera lens does, controlling the amount of light entering and subtly altering depth of field. But things break down at the retina, where instead of pixels or grains of silver halide evenly suspended in an emulsion, we find the light-sensitive nerve endings known by their shapes as rods and cones. Rods are very sensitive to low levels of light, but pretty much only detect light or dark. Cones are far less sensitive, requiring more light to respond, but they can detect colour. A tiny area at the centre of the retina on the optic axis called the fovea is populated with mostly cones, and when you look at anything, you are using your fovea. This gives a well-focused, high resolution colour image. The rest of the retina is mostly populated with rods, giving a lower resolution image, with relatively poor colour vision. Because nearly all of our optic cortex is devoted to processing the input from the fovea, we see whatever we are looking at very well – it’s sharp, clear, detailed and has exquisite colour rendition.

We actually have very little idea what we are seeing in our peripheral vision, and we can’t find out by trying to concentrate upon it – the moment we flick our eyes over to something at the periphery we see it instantly with the fovea and we are convinced that it was this sharp and this clear all along. This is the trick used by our visual system to make the most efficient use of our neural capacity, a kind of just-in-time image processing that lets us manage— very well—with only having good vision at the fovea. If it were possible to record the image in our brain it would probably seem unbelievable to us, sharp, detailed and coloured in the very centre, but low resolution and unsaturated outside that centre.

A camera does a far better job across the whole image, where degradation is quite small at the edges and corners with well-corrected lenses. Not only does a camera allow a sharp image in the periphery, it does something we cannot with our eyes—it allows an unfocused image in the periphery. But didn’t I just say our peripheral vision is low resolution? Yes, but we can’t tell that it is so, because as soon as we look there it sharpens up instantly courtesy of the fovea now pointing in that direction. Another difference lies in the field of view. It’s often claimed that a ‘standard’ lens, say 50mm focal length for a 35mm format camera, is a natural choice as it mimics the field of view of the human eye. That might be close to the truth for one eye, but we have two, and our brains seamlessly meld the images into one larger field of view. The field of view of a single eyeball is roughly the shape of the lens in a pair of aviator-style sunglasses, being limited above by our brows, below by our cheeks, and medially by our nose. Laterally, the sky’s the limit, most of us having the ability to see slightly behind us by a few degrees. Two eyes together are processed by our brains into a very wide strip, much wider than it is high. If you have access to a large white wall it is interesting to walk up to it until your nose just touches it, Using a finger you can detect the edges of your field of view whilst keeping your eyes fixed straight ahead. Above and below your finger will appear at your eyebrows and at your cheekbones, but laterally your finger will be off the wall and, at arm’s length, somewhere out in the plane of your ears before it disappears. Even a Widelux doesn’t come close.

So when I say the camera always lies, and so do your eyes, I’m really saying they don’t see things the same way, and neither corresponds exactly with the other. Cameras allow for another distortion that we don’t have with eyeballs—the depth compression that comes with varying focal lengths. You’ve all seen photographs of a figure silhouetted against a sunset, in which the figure is unnaturally large against the sun, both appearing to be roughly the same distance from the observer. Finally, one realises that painting is a third way of seeing, of recording a view of the world that doesn’t correspond with our inbuilt vision, nor with that of a camera. It allows perspectives to be changed, colours altered, details to be represented accurately or not, all in ways that don’t match what we are used to seeing. The very perfection of a photorealistic painting (and now we know that isn’t a good name for it!—it would be better called after the way it mimics the brain-processed image we perceive from our own eyes), is perhaps why we don’t care for it as art.

The Camera’s Lies Are Its Art

So now I’m beginning to understand why a photograph that appeals to me has that effect. It differs from natural vision in several ways, and it is these differences that make it worth contemplating. For example:

1. Change in field of view. I particularly like the square format, which restricts my view to something quite unlike my own vision. In itself, that immediately primes me with the knowledge that I am looking at something created, an image rather than reality. Obviously, I can arrange subject matter within that frame in various ways, emphasising some things, minimising others, employing dead space and so on, but all the while manipulating the effect on the viewer. Other formats allow other effects, and for anything other than square I can influence how it affects you simply by choosing landscape or portrait orientation. Naturally, choosing an unexpected orientation gives even more control.

2. Changing the palette. There’s a good reason why black and white photography survives, in that it forces us to concentrate on shape and form, on patterns, placement and contra-positions, on light, dark and contrast. Colour can be rich and fascinating, but it hasn’t those same qualities, and is best used for documenting a scene rather than presenting it in a new way. Placing contrasting colours in counterpoint would be an exception, as in an abstract photograph. Toning a print adds another layer of manipulation, creating an influence on the way an image is perceived—John Berger’s 1972 BBC documentary Ways of Seeing discusses this using the example of how an image will change its meaning when different music is played as it is viewed (by the way, that series is on YouTube and deserves a close look if you aren’t familiar with it).

3. Playing with differential focus. This is the big one for me, as it is something completely unavailable in ordinary vision. A portrait with the subject in focus and a pleasingly blurred background is something I can study in a photograph. It gives a sense of 3D like depth that is nearly as good as with a stereoscopic camera. With vision, the background is sharp as soon as I look at it. A photograph with huge depth of field (think of an f64-style landscape) isn’t interesting in this way. It’s interest is in the content, if the content itself is interesting. Any Ansel Adams landscape falls into that category and we can all agree he was very successful with them. Furthermore, the use of tilt-shift lenses can alter perspective in quite unnatural ways as used in architectural photography, and exploiting the Scheimpflug principle to the full with a view camera allows thin planes of focus to be angled in unusual ways that can appeal. The depth of focus is only a few inches deep here, but the plane of focus travels back from the corner of the vehicle to the window:

Summary

Our natural eyesight, photography and painting are three separate ways of representing the world around us, with less overlap than at first appears. All three tell their little lies, and it is in these differences, often unconsciously perceived, that each can teach us something new about our world. Poor Pietro Annigoni, for all his wonderful skill, still has Rodney Dangerfield’s complaint: “I don’t get no respect!” Maybe I now understand a little bit about why that is.

[Editor’s Note: For those interested in visual neurobiology and how it structures what and how we see, Margaret Livingstone’s Vision and Art: The Biology of Seeing is an excellent full-length treatment of the issues discussed above.]

The cause of these ruminations

The cause of these ruminations

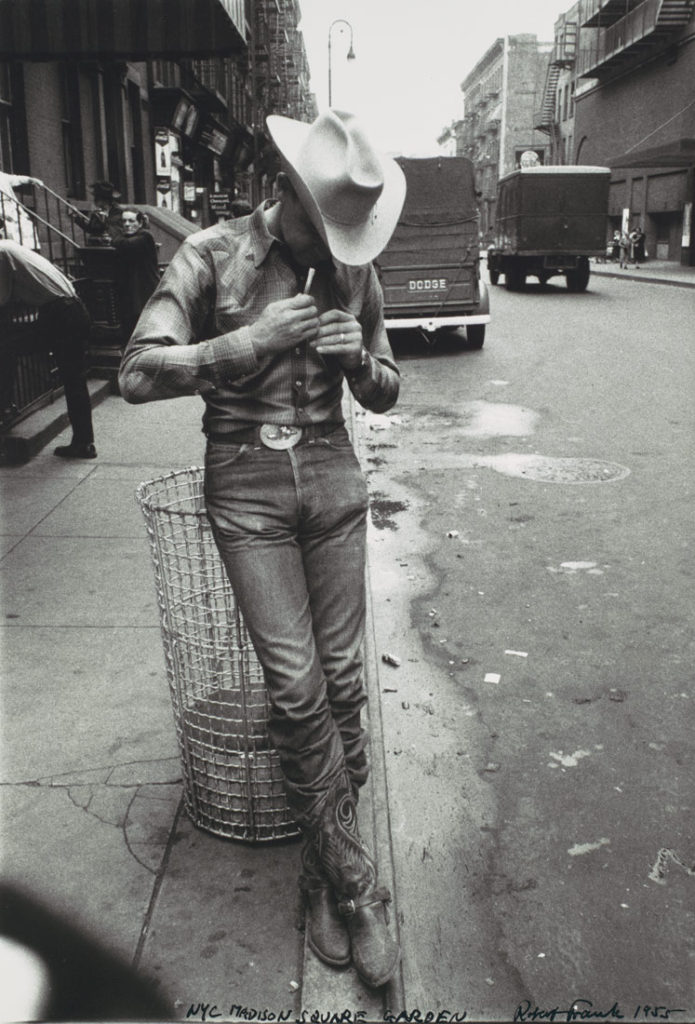

Car Window prints. All shot with a film camera. Not sharp, bad corners, harsh bokeh.

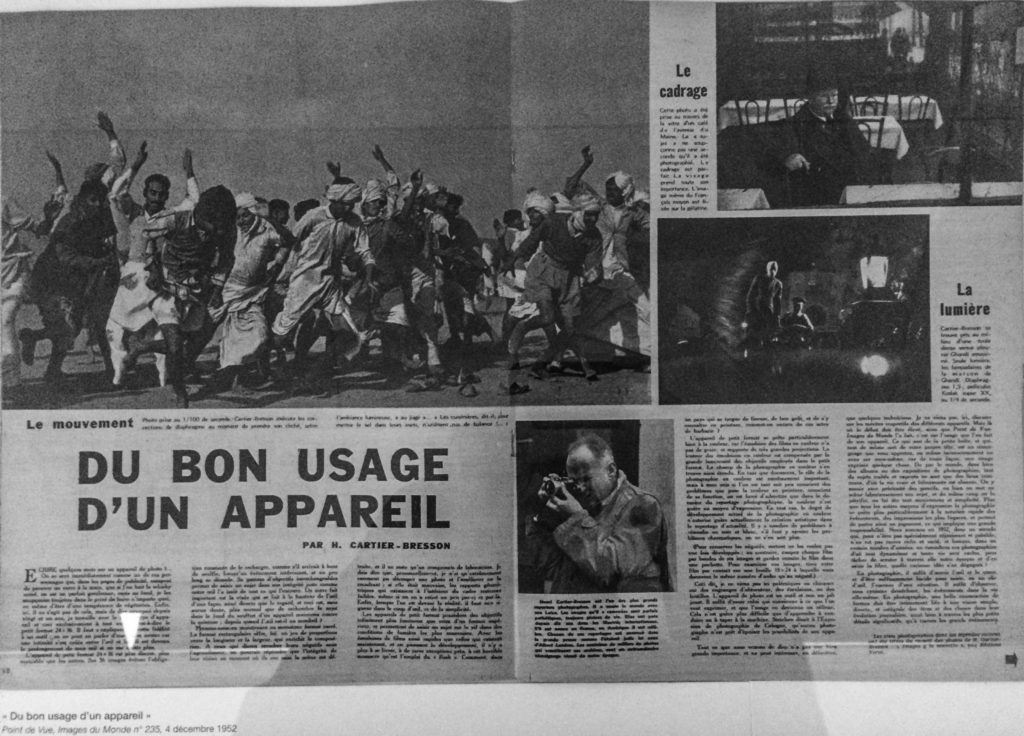

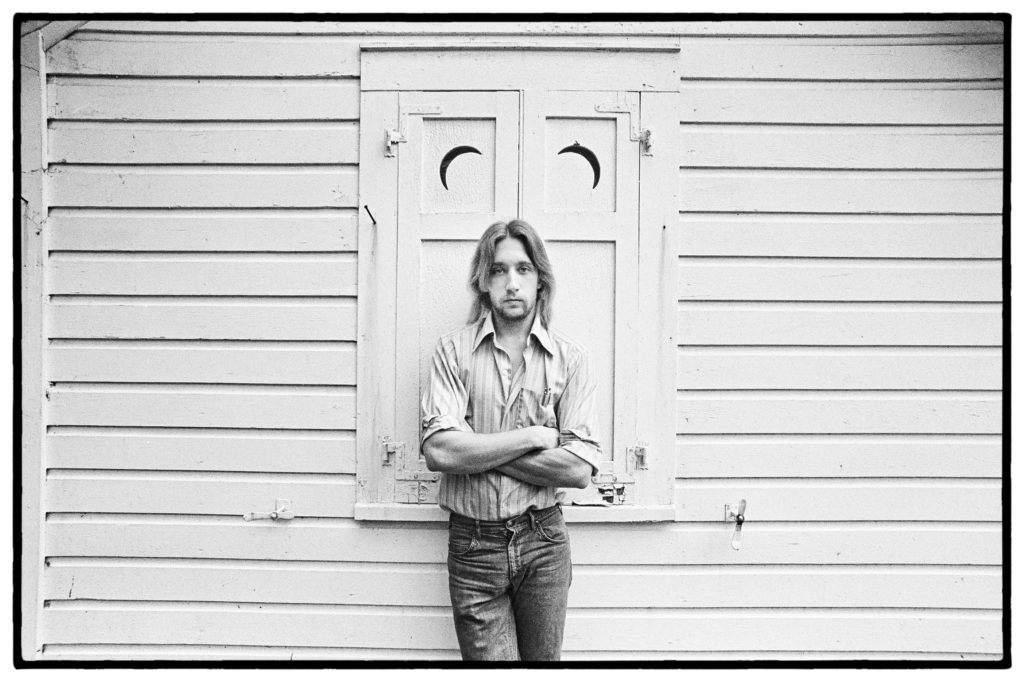

Car Window prints. All shot with a film camera. Not sharp, bad corners, harsh bokeh. A few years ago, while in Los Angeles, I saw a Walker Evans exhibition of his 1930’s Cuba photos at the Getty. Gorgeous 8×10 silver contact prints, one in particular, a frontal portrait of a Cuban stevedore that just blew me away with its simple beauty. That’s it, to the left, where, reproduced digitally and viewed on a computer monitor, it’s just another picture of some guy, nothing special. Were I to post it to some forum for critique I’m sure critics would take issue with any number of things – the framing, the lighting, the sharpness, the lack of acceptable bokeh etc etc, the usual herd animal opinions. Luckily, I saw that same print again in Paris this past Summer at the Evans exhibition at the Pompidou Center. So simple, yet profoundly arresting, impossible to look at and appreciate through the facile categories of sharpness, resolution, ease of capture, repeatabilty. It was a singular work that someone had laboriously produced in a darkroom. Art of the highest order, the exquisite confluence of singular critical decisions by Walker as to both construction and production, things that took time and thought and energy, all things the digital age promised us we could do without in our mad rush for the quick and easy.

A few years ago, while in Los Angeles, I saw a Walker Evans exhibition of his 1930’s Cuba photos at the Getty. Gorgeous 8×10 silver contact prints, one in particular, a frontal portrait of a Cuban stevedore that just blew me away with its simple beauty. That’s it, to the left, where, reproduced digitally and viewed on a computer monitor, it’s just another picture of some guy, nothing special. Were I to post it to some forum for critique I’m sure critics would take issue with any number of things – the framing, the lighting, the sharpness, the lack of acceptable bokeh etc etc, the usual herd animal opinions. Luckily, I saw that same print again in Paris this past Summer at the Evans exhibition at the Pompidou Center. So simple, yet profoundly arresting, impossible to look at and appreciate through the facile categories of sharpness, resolution, ease of capture, repeatabilty. It was a singular work that someone had laboriously produced in a darkroom. Art of the highest order, the exquisite confluence of singular critical decisions by Walker as to both construction and production, things that took time and thought and energy, all things the digital age promised us we could do without in our mad rush for the quick and easy.

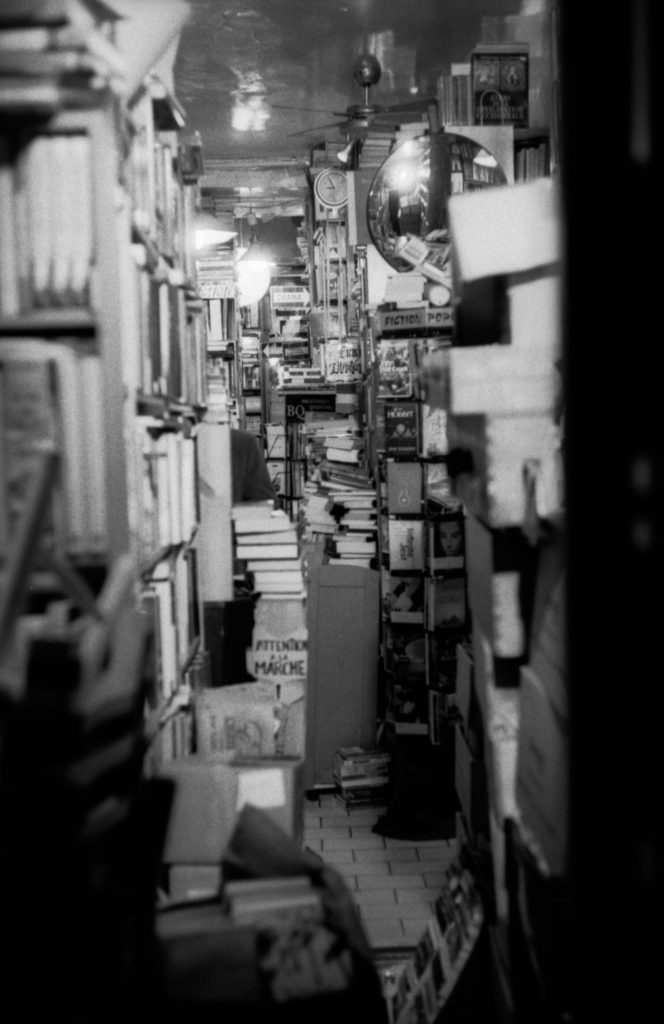

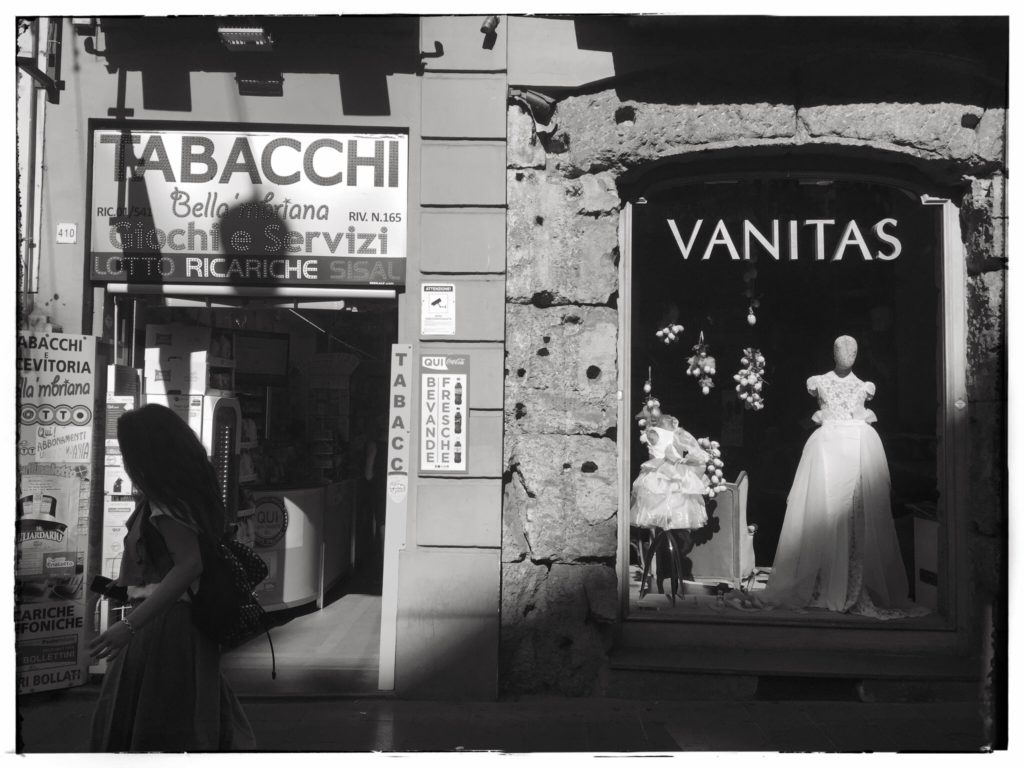

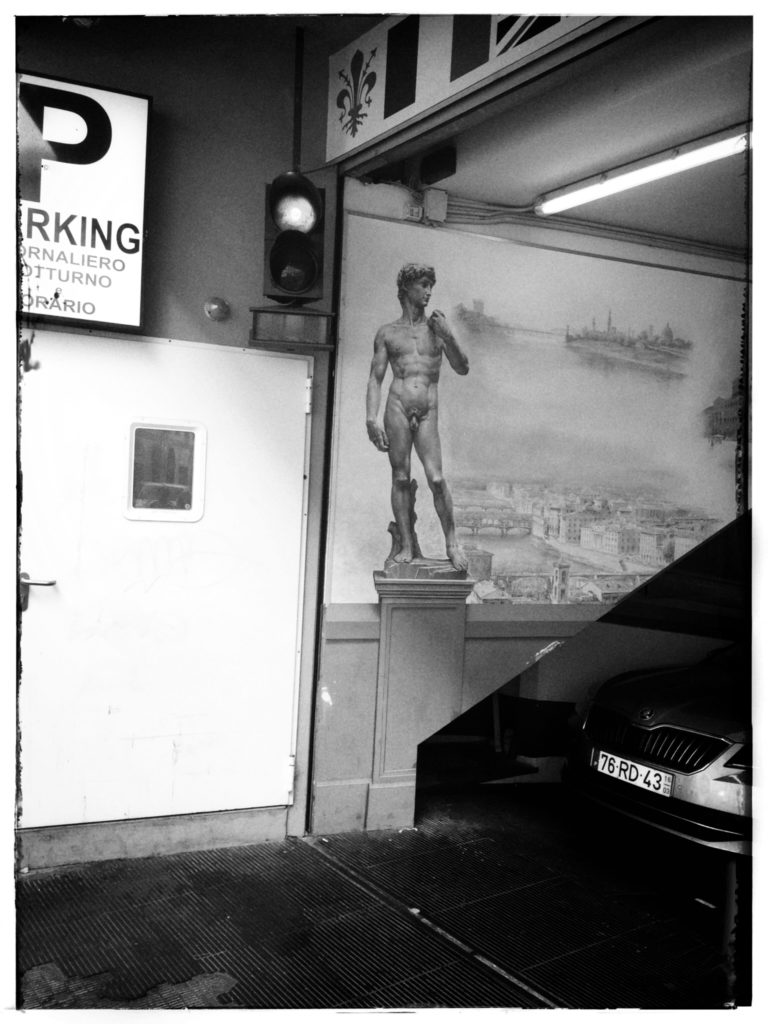

Florence

Florence